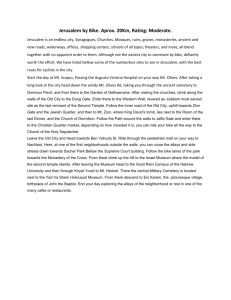

The Ancient Church of the Apostles: Revisiting

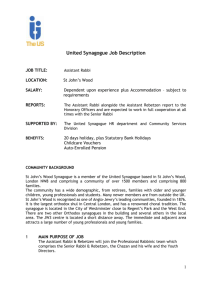

advertisement