Primary And Secondary Prophylaxis

advertisement

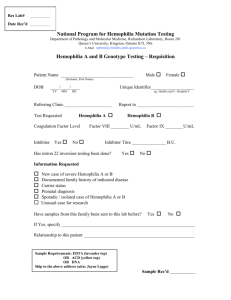

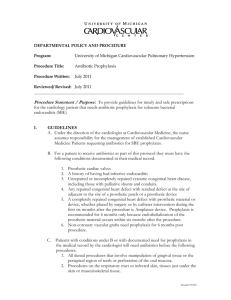

Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis |1 A. Rationale, Definition and Goals In hemophilia care, prophylaxis refers to the regular infusion of clotting factor concentrate to prevent bleeding episodes and related morbidity. This contrasts with episodic care in which bleeding episodes are treated on-demand to achieve hemostasis. The World Health Organization, the World Federation of Hemophilia, and the National Hemophilia Foundation recommend that primary prophylaxis be considered as first-line therapy for those with severe hemophilia. The ultimate goal is to prevent bleeding episodes and disease sequelea.1,2 In patients with hemophilia, both primary and/or secondary prophylaxis can be utilized and are discussed below and outlined in Table 1. Bleeding into joints and muscles can typically be prevented if a severely deficient patient's nadir level does not fall below 1%. Prevention of bleeding into joints and muscles leads to preservation of a "normal" musculoskeletal state and prevention of a disability. Maintaining a normal musculoskeletal state provides optimal therapy. Prophylaxis is considered optimal therapy and should be instituted early, often beginning at 1-2 years of age and prior to the onset of frequent bleeding, with the aim of keeping trough levels ≥1% between doses.1 This can be accomplished by giving 25-50 IU/kg factor VIII three times a week or every other day; or by giving 40-100 IU/kg factor IX two to three times a week.1 The National Hemophilia Foundation recommends that individuals treated on prophylaxis receive routine follow-up to document joint condition, complications, and the frequency of breakthrough bleeding. To-date there is no definitive guideline on when to stop prophylaxis1 and patients should work with their hemophilia treatment center (HTC) to determine their individualized plan. Those with pre-existing joint arthropathy may benefit from life-long prophylaxis. a. Primary Prophylaxis: Primary prophylaxis is the initiation of infusion therapy on a regular basis with the purpose of preventing hemorrhagic episodes for a prolonged, if not indefinite period of time. Primary prophylaxis can be technically defined in two ways: A) Continuous therapy after the first joint bleed or before age 2 years; B) Continuous therapy started before age 2 years and before a joint bleed has occurred (Table 1).3,4 b. Secondary Prophylaxis: Secondary prophylaxis is aimed at interrupting a bleeding pattern or preventing the advancement of joint disease. Secondary prophylaxis is often used for a defined period with the purpose of interrupting an established bleeding pattern, or providing coverage in order to “rest” an affected joint.4 Secondary prophylaxis can be: A) Continuous (long-term); 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis |2 B) Intermittent (short-term). The amount of long-term damage a joint develops however, may not be completely altered by secondary prophylaxis. The frequency of infusion therapy required may be every other day to effectively prevent recurrent bleeding; a higher nadir level than that required in primary prophylaxis is often required to interrupt a bleeding pattern or rest a joint (Table 1). Table 1. Definitions of Prophylaxis Therapy4,5 Type of Therapy Definition Primary prophylaxis A Continuous therapy after first joint bleed or before age 2 years Primary prophylaxis B Continuous therapy started at age 2 before a joint bleed Secondary prophylaxis A Continuous therapy started after ≥2 bleeds or at an age ≥2 years Secondary prophylaxis B Intermittent therapy due to frequent bleeds B. History of Prophylaxis Primary prophylaxis is based upon the observation that moderate deficient patients bleed less frequently than severe deficient patients and usually in association with some intercurrent injury. Prophylaxis therefore aims to take a severe deficient patient and allow them to maintain coagulation factor levels equivalent to a moderate deficient patient (i.e. keep nadir levels prior to each infusion equal to or greater than 1%). The goal of this method of infusion therapy is to prevent the sequelea of severe hemophilia, specifically joint and muscle damage. Secondary prophylaxis has been employed since the advent of reasonable replacement therapy and primarily has been used in countries where replacement therapy has been instituted after bleeding episodes have been experienced (definition of episodic care). Published data regarding prophylaxis largely comes from studies performed in Sweden and the Netherlands. Although two studies highlighted the importance and benefits of prophylaxis on hemophilic arthropathy, they did not make comparisons to on-demand only treatment.6,7 Others have published results detailing the benefits of prophylaxis and have documented not only prevention of joint arthropathy, but also demonstrated an improved quality of life for those receiving preventative care.8-12 Most recently, Manco-Johnson et al. published the first U.S. prospective, randomized study in the New England Journal of Medicine comparing prophylactic therapy (n=32) to enhanced episodic infusion therapy (n=33) in boys (1-21/2 years old) with severe factor VIII deficiency.13 The study continued until the boys reached six years of age and results showed that although those on prophylaxis consumed up to three times as much factor VIII 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis |3 concentrate than those using enhanced on-demand therapy, the prophylaxis group experienced a median of 1.2 hemorrhages/year compared to 17.1 hemorrhages/year in the episodic treatment arm. As a result, the on-demand group had a six-fold higher relative risk of joint damage (p<0.001) as assessed by X-ray, MRI and physical examination. Additionally, three of the 33 patients in the on-demand group experienced a serious lifethreatening hemorrhage compared to none in the prophylactic treatment arm (p=0.24). The primary conclusion of this study is that prophylaxis not only prevents joint damage but also decreases the frequency of hemarthrosis and serious non-joint hemorrhage. C. Prophylaxis Considerations: Central Venous Access Devices Independent of patient choice of treatment regimens, prophylactic or on-demand, there are certain aspects of care that must be taken into consideration. One of the most important of these considerations, specifically in very young children, is venous access. a. Venous Access Devices: The use of peripheral veins to infuse clotting factor concentrate is the method of choice; however, if this method is not possible, a central venous access device (CVAD) may be used as a bridge. CVADs are typically used in young patients who require clotting factor concentrate but are unable to obtain venous access regularly at home.14-17 They are used in about 30% of those on every-other-day prophylaxis and in 90% of those receiving daily immune tolerance induction therapy.18 CVADs have benefits and risks and their use should be discussed with the patient and/or family to determine the most appropriate treatment option (Table 2). CVADs should only be used as long as medically necessary. i. Internal Catheter/Ports: Typically, an internal port is comprised of a subcutaneous reservoir that is surgically implanted into either the chest (Port-A-Cath) or in the arm (PassPort). The port appears as a bump under the skin.14 A radio-opaque catheter (not transparent to X-rays or other radiation) is attached to the reservoir with the free catheter end projecting into the junction between the superior vena cava and the right atrium. Ports are often used in those who may easily displace an external CVAD (i.e. children).16 Ports require a needle to puncture the skin to access the reservoir which can cause pain, anxiety and skin breakdown. They are typically inserted in an operating room or radiology suite. A benefit of this device, especially for children who enjoy swimming or are learning to swim, is that this device allows for full submersion under water and has an associated lower risk of infection compared to an external catheter. ii. External Catheter: External catheters exit the skin through a subcutaneous tunnel or directly at the site of entry into the skin. For tunneled catheters, a tunnel is created under the skin through which the catheter is positioned. 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis |4 The distal end of the catheter is located between the superior vena cava and the right atrium. An X-ray will verify the location of the catheter tip. The proximal end of the catheter exits the skin and is typically located in the chest region.16 Nontunneled catheters are secured in place at the insertion site. With this treatment, the catheter and attachments protrude directly from the skin. Patients with an external catheter cannot be submerged in water. iii. Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC): A PICC line is a central catheter that is inserted into a vein in the arm. This catheter enters the vein and continues through the venous system until the tip reaches the superior vena cava. A guide wire located in the catheter line allows for the movement of the line through the veins. Just as with an external catheter, those with a PICC line cannot be submerged in water. Table 2. Commonly Used CVADs and Brief Descriptions CVAD Description Potential Duration of Use Internal Cather/Port • Surgically implanted under the skin usually in the chest above the heart • Patient places needle into a reservoir connected to the catheter to infuse Several years External Catheter • Surgically implanted under the skin and commonly inserted into a vein in the neck or chest • Patient infuses through the external end of the catheter • Inserted into a vein in the arm •Patient infuses through the external end of the catheter ≥1 year • Located in a vein near the heart, usually through the chest • Patient infuses into a cap near the end of the tube The external catheter is changed frequently to keep the area sterile (Tunneled) Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Weeks to months (PICC) External Catheter (Nontunneled) b. Benefits of CVADs: The three most common benefits of CVADs in hemophilia are: 1) the ease with which clotting factor concentrate can be infused; 2) the ability to institute early prophylaxis and independent home infusion therapy; and 3) the reduction in the risk of long-term peripheral vein damage.19 CVADs allow patients and their families the freedom to infuse at home when peripheral venous access is not possible, particularly in very small children, and thus reduces the number of hospital, physician, and clinic visits. 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis |5 c. Risks of CVADs: The two most common risks associated with the use of a CVAD are infection and thrombosis. Other less common risks include hemorrhagic complications and occlusive complications caused by the device itself. i. Infectious Complications: The placement of indwelling venous access devices interrupts the body’s normal defense mechanisms to prevent infection (bacteria) from entering the blood-stream. Individuals with any CVAD are subject to experiencing a bacterial infection in the blood (bacteremia or sepsis). These infections may be severe or life-threatening if prompt attention is not sought or provided. It is estimated that between 855% of patients with a CVAD get an infection.20-22 Infections are most common in patients under two years of age who require frequent infusions and in those with inhibitors. Signs of an infection include fever, reddening of the skin at the point of entry or along the catheter tract, and/or drainage at the insertion site. Antipyretic medication may be given as outlined in Table 3; however, the patient should be immediately evaluated by a physician. Blood cultures should be taken from the CVAD, and peripherally if possible. Blood cultures are permitted to grow for 72 hours. In the interim, a dose of broad spectrum antibiotics should be administered as a precautionary measure through the CVAD. If a culture tests positive for bacteria, sensitivity testing will be performed to determine the appropriate antibiotic treatment regimen. Table 3. Antipyretic Dosage Medication Pediatric Dosage Adult Dosage Acetaminophen 10-15 mg/kg, every 4-6 hours* 325-500 mg, every 4-6 hours^ Non-steroidal antiinflammatory (e.g., Ibuprofen)Δ 10 mg/kg, every 6-8 hours 200-400 mg, every 4-6 hours Due to the potential for liver damage: *No more than 5 doses of acetaminophen in a 24 hour period; maximum daily dose should not exceed 90 mg/kg/day ^Maximum daily dose should not exceed 4 g/day ΔNon-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications should only be taken in individuals with bleeding disorders if directed by a physician Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria are types of organisms that are common in CVADs (Table 4). They are distinguished by their ability to retain a crystal violet stain. This technique was developed in the 1800’s and is called Gram staining.23 Gram-positive bacteria retain the crystal violet stain while Gram-negative bacteria do not. Most pathogens in humans are Gram- 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis |6 positive organisms and usually eradicated with antibiotic therapy. Gramnegative organisms tend to be more virulent and difficult to eradicate due to having an outer endotoxic layer that triggers an immune response. Bacteria in or around a catheter also form a slimy matrix, called biofilm, that can inhibit successful clearing with antibiotics.24 In this case, antibiotic lock therapy, a method of allowing an antibiotic to sit within the catheter for up to 48 hours, may be indicated. Different fungal species can also cause CVAD infection. Table 4. Types of Organisms Typically Found in CVADs Pathogen Name Type of pathogen Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus saprophyticus Gram-positive Comments Coagulase-positive Staphylococcus aureus Gram-positive Enterococcus species Enterobacter species, E. coli, K. pneumonia, P. aeruginosa Gram-positive Gram-negative Fungus (yeast) Requires aggressive treatment as organism is highly virulent May clear with 4 weeks of systemic antibiotics and antibiotic lock therapy; however, clearance of infection may require catheter removal Known to cause infective endocarditis Causes 10% of all infections Likely to be cleared with use of ampicillin; or vancomycin for ampicillin-resistant strains Propensity to form a biofilm in the catheter, making it difficult to clear the infection Need to be aggressive with first round of antibiotic treatment to prevent recurrence of infection To prevent antibiotic resistance, therapy should be continued for at least 7-14 days Candida species Most common cause of catheterrelated infection Likely to be cleared if treated with a 10-14 day antibiotic regimen Low success rate of clearing infection High associated mortality and morbidity May require removal of the central line Other risk factors for infection include: poor oral hygiene and/or the presence of dental cavities or abscesses; and medical conditions that 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis |7 compromise the immune system.19 Infections can also occur due to poor sterile technique when accessing the CVAD. If more than one infection occurs in a device, a follow-up investigation is warranted and the medical provider should discuss techniques to lessen future risk of infection if continued CVAD use is required. Current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention strategies to prevent catheter-related infections can be found at: http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/guidelines/bsi-guidelines-2011.pdf. ii. Thrombosis: Thrombosis is the development of a blood clot that obstructs the flow of blood through a vessel. Patients with hemophilia can develop blood clots most commonly when a CVAD is present.19 The clot can form within the reservoir, within the catheter tube, or directly inside the lumen of a blood vessel. Clots that form within the reservoir or catheter may be caused by inappropriate flushing or anticoagulation. A fibrin sheath may also form around the catheter leading to fluid leakage or complete blockage at the catheter tip. It is also possible for the catheter to irritate the lumen of the vessel, leading to thrombus formation. The long-term consequences from CVAD-related thrombosis in children with hemophilia are not completely known at this time. To dissolve a clot, thrombolytic therapy may be used. If clot dissolving medications prove ineffective, the catheter may require removal and/or replacement. Depending upon patient symptoms, the utility of the existing line, and the extent of clot formation, a patient may need to have the CVAD removed. iii. Hemorrhagic Complications: Individuals with hemophilia may have low enough factor levels, prior to the next infusion, such that the placement of the needle into the port may precipitate the development of a hematoma around the port reservoir. This may in turn lead to the development of a problem with the port or a theoretical increased risk of infection. A blow to a CVAD may also precipitate a bleeding episode despite the use of primary prophylaxis. iv. Other Complications: Although uncommon, it is possible for the line of the catheter to fracture and travel to another part of the body such as the heart or lungs.19 The catheter can also separate from the reservoir causing infiltration of clotting factor concentrate into the surrounding tissue without delivery into the blood stream. Finally, an opening can form in the skin covering the reservoir from skin dehiscence. These complications require corrective action. 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis |8 d. Removal of a CVAD: A CVAD should be removed as soon as is feasible due to the inherent risks of these devices. Circumstances that may warrant immediate removal include: an infection cannot be cleared; catheter occlusion; line fracture; or if a thrombosis has occurred in a vessel. The optimal method of factor infusion is peripheral venipuncture; this should be used as soon as the patient or family is able to master this technique. D. Dental Prophylaxis Dental treatment can be risky and cause bleeding which can be severe or even fatal in individuals with bleeding disorders. Therefore, dental care and prevention should be stressed by an HTC. Preventative actions will help maintain good oral health. In those with bleeding disorders, teething alone rarely causes bleeding; however, if minor bleeding occurs, the HTC should be notified to take the appropriate measures. Steps should also be taken to ensure the individual’s dentist has the following information on file: • • • • • Type and severity of the bleeding disorder Presence of inhibitor or venous access device List of current medications Knowledge of appropriate pre-dental treatment requirements HTC contact information Dental procedures in those with hemophilia can be divided into two broad categories: lowrisk and high-risk. Low-risk procedures do not require special medical recommendations and include the placement of sealants, incipient restorations and restorations that do not require block injections, including root canal therapy on the upper teeth. High-risk procedures require dental prophylaxis and are described below. Ideally, these procedures are performed on the day of regularly scheduled prophylaxis; alternatively individuals are infused on the day of treatment if utilizing an on-demand regimen. a. Tooth Extractions: Individuals with hemophilia that require a dental extraction should be infused with an 80-100% correction prior to extraction.25 A full-mouth extraction should be performed in one to two appointments. Additionally, antifibrinolytic therapy should be started on the day of treatment and continued for ten days. b. Block Injections: If a block injection is required, a 40% factor correction is recommended.25 Alternatively, desmopressin may be used when appropriate. c. Oral Surgery: Oral surgery in an individual with a bleeding disorder requires formulation of a surgery plan. The plan should be communicated to all of those participating in the patient’s care. Topics of discussion include whether clotting factor concentrate and/or antifibrinolytics are required and the dosage, the type 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis |9 and location of anesthetic coverage, and whether antibiotic coverage is recommended. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AADP) recommendations for antibiotic coverage are listed in Table 5.26 Table 5. AADP Antibiotic Coverage Recommendations Situation Agent Adults Pediatrics Oral Amoxicillin 2g 50 mg/kg Unable to take oral medication Ampicillin, Cefazolin or Ceftriaxone 2 g IM or IV 1g IM or IV 50 mg/kg IM or IV 50 mg/kg IM or IV Allergic to penicillin or ampicillin – oral Cephalexin, Clindamycin, Azithromycin or Clarithoromycin 2g 600mg 500mg 50 mg/kg 20 mg/kg 15 mg/kg 1g IM or IV 600mg IM or IV 50mg/kg IM or IV 20mg/kg IM or IV Allergic to penicillin or ampicillin and unable to take oral medication Cefazolin or Ceftriaxone, Clindamycin d. Periodontal Treatment: Individuals with severe periodontal disease may require surgery. Patients on a regular clotting factor concentrate or prophylaxis schedule are encouraged to have the surgery performed on the same day as they are scheduled to infuse. Patients using on-demand therapy require a 40-80% correction prior to surgery. Antifibrinolytic agents may be used to stabilize the clot following surgery. e. Dental Emergencies: Dental emergencies in individuals with a bleeding disorder require immediate attention and the patient should be seen by a dentist as soon as possible. Examples of dental emergencies include: discoloration of soft tissue; broken teeth or black areas on the tooth; swollen, puffy or inflamed gums; dental abscesses; frenulum tear; liver clot; eruption hematoma; and evulsed or broken teeth. For more information on Dental Management for individuals with bleeding disorders refer to the IHTC manual entitled Management Issues: Hemophilia and von Willebrand Disease (Section 15). E. Compliance with Home-Based Prophylaxis Therapy The institution of either primary or secondary prophylaxis requires a compliant patient/family situation, especially if an indwelling venous access catheter is used. Not all patients/families are optimal candidates. The caregiver should adequately explain the need for compliance, the medical follow-up required and provide sufficient education so that the patient and family are equipped to handle their care. Families with no family 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis | 10 history, or experience with hemarthrosis and other complications may have some difficulty realizing the life-long benefits of prophylaxis.27 In a recent European study, reasons cited for low compliance to a prophylactic regimen included: disappearance of symptoms; forgetfulness; lack of time; and inconvenience of treatment.28 This study also cited the most common reasons for positive compliance as: young age, time spent in a hemophilia treatment center, and the quality of the relationship with the medical team.28 Acceptance of the diagnosis and difficulties with venous access have also been cited as reasons for low compliance.29 Ultimately, to achieve optimal compliance, a caregiver must understand the patient’s and family’s needs, desires, expectations, social environment, self-image, and desire for quality of life.27 F. Infusion Logs Infusion logs are an important tool for patients, families and HTCs. Infusion logs allow HTCs to manage a patient’s care more accurately and effectively, and enable patients to take a more proactive approach to their own healthcare. Logs track clotting factor concentrate infusion date and time, purpose, site of infusion, and outcome. Some insurance companies require patients to keep infusion logs for claim reimbursement. Infusion logs can be kept on paper, through phone applications, or via other electronic records such as that provided by the American Thrombosis and Hemostasis Network (ATHN) called ATHNadvoy. G. Financial Issues Hemophilia therapy is an expensive medical condition with the primary cost arising from factor replacement.30 The cost of primary or secondary prophylaxis is more per year as compared to on-demand therapy; however, the health-related quality of life and medical outcomes in patients on prophylaxis is consistently better. 31 Additionally, expenses incurred from surgery and loss of work days is lower in those on prophylaxis. 10 The cost of the long-term sequelea of hemophilia such as disability or need for joint replacement need to be weighed when considering these infusion programs. One is essentially placing the cost of hemophilia care "up-front" when instituting primary prophylaxis for patients. The National Hemophilia Foundation strongly encourages primary prophylaxis as a first-choice of therapy in severe deficient hemophilia A and B. Patients and families must be informed about issues related to cost. Optimally, insurers should be educated and "buy-in" to the concept of primary prophylaxis. H. Product Availability Patients on prophylactic therapy consume more clotting factor concentrate per year than those using on-demand therapy. The optimal treatment today is the use of recombinant clotting factor concentrate. A theoretical unlimited supply of recombinant product should be available as recombinant clotting factor concentrate does not rely on human plasma for its production. 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis | 11 I. Psychosocial Implications Many publications have documented the psychosocial implications associated with chronic disease and hemophilia in the U.S. as well as abroad (refer to the IHTC Manual: Management Issues: Hemophilia and von Willebrand Disease for more detailed information).32 Prior to prophylaxis, school absenteeism was common due to the frequency of bleeding episodes and joint problems; however, school integration and attendance is less of a problem since the advent of prophylaxis and home treatment. 33-35 Prophylaxis in patients with hemophilia may also protect these individuals from psychosocial complications sometimes seen in patients with other rare bleeding disorders.36 The exact reason for this correlation is not well understood but is hypothesized to be due to allowing children to lead more “normal” lives. This may be due to the observation that prophylaxis leads to improved social and academic participation and improves subsequent work opportunities in those with severe hemophilia. J. Future of Prophylaxis Given the convincing evidence documented on the benefits of prophylaxis compared to ondemand therapy, and due to the recommendations by the National Hemophilia Foundation1, the hemophilia field has now focused on identifying the optimal prophylactic regimen rather than further delineating the differences between prophylaxis and ondemand treatment. An “optimal” regimen takes into account: whether or not the primary goal is only to maintain joint function or to maintain near-normal hemostasis and thus participation in normal daily activities. Furthermore, methods to decrease the expense of prophylaxis are being investigated. In regard to the latter, studies from Malmö, Sweden have shown that patients using daily prophylaxis for one year consumed 30% less clotting factor concentrate (p<0.04) than those using the standard prophylactic regimen (i.e., either every other day or three times/week) or pharmacokinetic-specific dosing.37 However, the total number of bleeding events increased in some patients utilizing the daily prophylaxis regimen. This was associated with a decreased quality of life. Further studies are needed to determine the cause of increased bleeding, and hence optimal regimens. K. References: 1. Medical and Scientific Advisory Council (MASAC) recommendation #179: MASAC recommendation concerning prophylaxis (regular administration of clotting factor concentrate to prevent bleeding). 2007. (Accessed January 7, 2010, at http://www.hemophilia.org/NHFWeb/MainPgs/MainNHF.aspx?menuid=57&contentid=1007.) 2. Berntorp E, de Moerloose P, Ljung RC. The role of prophylaxis in bleeding disorders. Haemophilia 2010;16 Suppl 5:189-93. 3. Petrini P, Lindvall N, Egberg N, Blombäck M. Prophylaxis with factor concentrates in preventing hemophilic arthropathy. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1991;13:280-7. 4. Ljung R. Prophylactic therapy in haemophilia. Blood Rev 2009;23:267-74. 5. Donadel-Claeyssens S, Management EPNfH. Current co-ordinated activities of the PEDNET (European Paediatric Network for Haemophilia Management). Haemophilia 2006;12:124-7. 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis | 12 6. Nilsson IM, Berntorp E, Löfqvist T, Pettersson H. Twenty-five years' experience of prophylactic treatment in severe haemophilia A and B. J Intern Med 1992;232:25-32. 7. van den Berg HM, Fischer K, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, et al. Long-term outcome of individualized prophylactic treatment of children with severe haemophilia. British Journal of Haematology 2001;112:561-5. 8. Aledort LM, Haschmeyer RH, Pettersson H. A longitudinal study of orthopaedic outcomes for severe factor-VIII-deficient haemophiliacs. The Orthopaedic Outcome Study Group. J Intern Med 1994;236:391-9. 9. Fischer K, Astermark J, van der Bom JG, et al. Prophylactic treatment for severe haemophilia: comparison of an intermediate-dose to a high-dose regimen. Haemophilia 2002;8:753-60. 10. Steen Carlsson K, Höjgård S, Glomstein A, et al. On-demand vs. prophylactic treatment for severe haemophilia in Norway and Sweden: differences in treatment characteristics and outcome. Haemophilia 2003;9:555-66. 11. Brackmann HH, Eickhoff HJ, Oldenburg J, Hammerstein U. Long-term therapy and ondemand treatment of children and adolescents with severe haemophilia A: 12 years of experience. Haemostasis 1992;22:251-8. 12. Carlsson M, Berntorp E, Björkman S, Lindvall K. Pharmacokinetic dosing in prophylactic treatment of hemophilia A. European Journal of Haematology 1993;51:247-52. 13. Manco-Johnson MJ, Abshire TC, Shapiro AD, et al. Prophylaxis versus episodic treatment to prevent joint disease in boys with severe hemophilia. The New England Journal of Medicine 2007;357:535-44. 14. Ewenstein BM, Valentino LA, Journeycake JM, et al. Consensus recommendations for use of central venous access devices in haemophilia. Haemophilia 2004;10:629-48. 15. Ljung R. The risk associated with indwelling catheters in children with haemophilia. Br J Haematol 2007;138:580-6. 16. Komvilaisak P, Connolly B, Naqvi A, Blanchette V. Overview of the use of implantable venous access devices in the management of children with inherited bleeding disorders. Haemophilia 2006;12 Suppl 6:87-93. 17. Ewenstein BM, Valentino LA, Journeycake JM, et al. Consensus recommendations for use of central venous access devices in haemophilia. Haemophilia 2004;10:629-48. 18. Valentino LA, Kawji M, Grygotis M. Venous access in the management of hemophilia. Blood Rev 2011;25:11-5. 19. Medical and Scientific Advisory Council (MASAC) document #115- MASAC recommendation regarding central venous access devices including ports and passports. 2001. (Accessed at http://www.hemophilia.org/NHFWeb/MainPgs/MainNHF.aspx?menuid=57&contentid=297.) 20. Medeiros, Miller, Rollins, Buchanan. Contrast venography in young Haemophiliacs with implantable central venous access devices. Haemophilia 1998;4:10-5. 21. Liesner RJ, Vora AJ, Hann IM, Lilleymann JS. Use of central venous catheters in children with severe congenital coagulopathy. Br J Haematol 1995;91:203-7. 22. Blanchette VS, Al-Musa A, Stain AM, Ingram J, Fille RM. Central venous access devices in children with hemophilia: an update. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1997;8 Suppl 1:S11-4. 23. Austrian R. The Gram stain and the etiology of lobar pneumonia, an historical note. Bacteriol Rev 1960;24:261-5. 24. Talsma SS. Biofilms on medical devices. Home Healthc Nurse 2007;25:589-94. 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis | 13 25. Brewer A, Correa M. Guidelines for dental treatment of patients with inherited bleeding disorders. Treatment of Hemophilia. http://www.lhsc.on.ca/Health_Professionals/Bleeding_Disorders/TOH-40_Dental_treatment.pdf. 2006. 26. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD). Guideline on Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Dental Patients at Risk for Infection. Clinical Guidelines Reference Manual 2011;33:265-9. 27. Coppola A, Cerbone AM, Mancuso G, Mansueto MF, Mazzini C, Zanon E. Confronting the psychological burden of haemophilia. Haemophilia 2011;17:21-7. 28. De Moerloose P, Urbancik W, Van Den Berg HM, Richards M. A survey of adherence to haemophilia therapy in six European countries: results and recommendations. Haemophilia 2008;14:931-8. 29. Santagostino E, Mancuso ME. Barriers to primary prophylaxis in haemophilic children: the issue of the venous access. Blood Transfus 2008;6 Suppl 2:s12-6. 30. Colowick AB, Bohn RL, Avorn J, Ewenstein BM. Immune tolerance induction in hemophilia patients with inhibitors: costly can be cheaper. Blood 2000;96:1698-702. 31. Royal S, Schramm W, Berntorp E, al e. Quality-of-Life differences between prophylaxis treatment and on-demand factor replacement therapy in European haemophilia patients. Haemophilia 2002;8:44-50. 32. Psychosocial Care for People with Hemophilia- The World Federation of Hemophila. 2007. (Accessed at 33. Plug I, Peters M, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, et al. Social participation of patients with hemophilia in the Netherlands. Blood 2008;111:1811-5. 34. Markova I, MacDonald K, Forbes C. Integration of haemophilic boys into normal schools. Child Care Health Dev 1980;6:101-9. 35. Shapiro AD, Donfield SM, Lynn HS, et al. Defining the impact of hemophilia: the Academic Achievement in Children with Hemophilia Study. Pediatrics 2001;108:E105. 36. Clemente C, Tsiantis J, Sadowski H, et al. Psychopathology in children from families with blood disorders: a cross-national study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;11:151-61. 37. Lindvall K, Astermark J, Bjorkman S, et al. Daily dosing prophylaxis for haemophilia: a randomized crossover pilot study evaluating feasibility and efficacy. Haemophilia : the official journal of the World Federation of Hemophilia 2012. 2012 Copyright Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Inc. Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis | 14