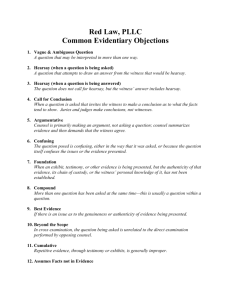

Objections to Evidence and Testimony

advertisement