social loafing in a competitive context

advertisement

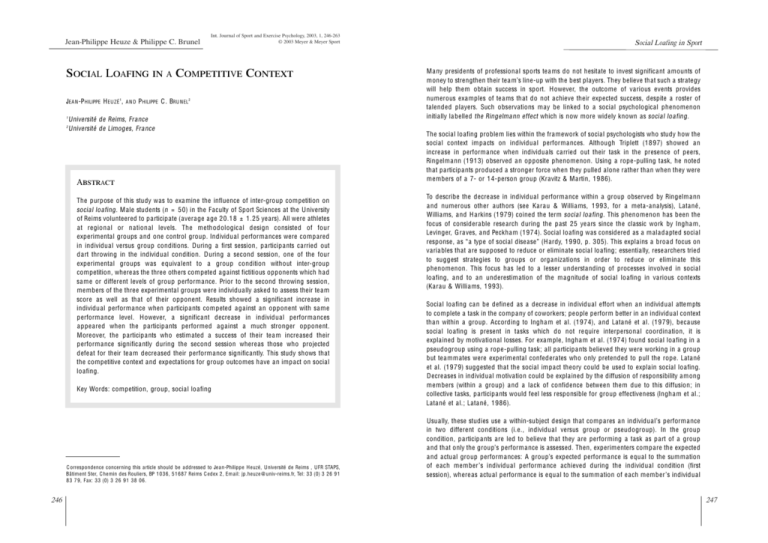

Jean-Philippe Heuze & Philippe C. Brunel Int. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2003, 1, 246-263 © 2003 Meyer & Meyer Sport SOCIAL LOAFING IN A COMPETITIVE CONTEXT JEA N -P HILIPPE H EUZÉ 1 , 1 2 AND P HILIPPE C . BRU NEL2 Université de Reims, France Université de Limoges, France ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to examine the influence of inter-group competition on social loafing . Male students (n = 50) in the Faculty of Sport Sciences at the University of Reims volunteered to participate (average age 20.18 ± 1.25 years). All were athletes at region al or n ation al levels. The methodological design consisted of four experimental groups and one control group. Individual performances were compared in individual versus group conditions. During a first session, participants carried out dart throwing in the individual condition. During a second session, one of the four experimental groups was equivalent to a group condition without inter-group competition, whereas the three others competed against fictitious opponents which had same or different levels of group performance. Prior to the second throwing session, members of the three experimental groups were individually asked to assess their team score as well as that of their opponent. Results showed a significant increase in individual performance when participants competed against an opponent with same performance level. However, a significant decrease in individual performances appeared when the participants performed against a much stronger opponent. Moreover, the participants who estimated a success of their team increased their performance significantly during the second session whereas those who projected defeat for their team decreased their performance significantly. This study shows that the competitive context and expectations for group outcomes have an impact on social loafing. Key Words: competition, group, social loafing C orrespondence concerning this article should be addressed to Jean-Philippe Heuzé, Université de Reims , UFR STAPS, Bâtiment 5ter, C hemin des Rouliers, BP 1036, 51687 Reims C edex 2, Email: jp.heuze @ univ-reims.fr, Tel: 33 (0) 3 26 91 83 79, Fax: 33 (0) 3 26 91 38 06. 246 Social Loafing in Sport Many presidents of professional sports teams do not hesitate to invest significant amounts of money to strengthen their team’s line-up with the best players. They believe that such a strategy will help them obtain success in sport. However, the outcome of various events provides numerous examples of teams that do not achieve their expected success, despite a roster of talended players. Such observations may be linked to a social psychological phenomenon initially labelled the Ringelmann effect which is now more widely known as social loafing . The social loafing problem lies within the framework of social psychologists who study how the social context impacts on individual performances. Although Triplett (1897) showed an increase in performance when individuals carried out their task in the presence of peers, Ringelmann (1913) observed an opposite phenomenon. Using a rope-pulling task, he noted that participants produced a stronger force when they pulled alone rather than when they were members of a 7- or 14-person group (Kravitz & Martin, 1986). To describe the decrease in individual performance within a group observed by Ringelmann and numerous other authors (see Karau & Williams, 1993, for a meta-analysis), Latané, Williams, and H arkins (1979) coined the term social loafing . This phenomenon has been the focus of considerable research during the past 25 years since the classic work by Ingham, Levinger, G raves, and Peckham (1974). Social loafing was considered as a maladapted social response, as “a type of social disease” (H ardy, 1990, p. 305). This explains a broad focus on variables that are supposed to reduce or eliminate social loafing; essentially, researchers tried to suggest strategies to groups or organizations in order to reduce or eliminate this phenomenon. This focus has led to a lesser understanding of processes involved in social loafing, and to an underestimation of the magnitude of social loafing in various contexts (Karau & Williams, 1993). Social loafing can be defined as a decrease in individual effort when an individual attempts to complete a task in the company of coworkers; people perform better in an individual context than within a group. According to Ingham et al. (1974), and Latané et al. (1979), because social loafing is present in tasks which do not require interpersonal coordination, it is explained by motivational losses. For example, Ingham et al. (1974) found social loafing in a pseudogroup using a rope-pulling task; all participants believed they were working in a group but teammates were experimental confederates who only pretended to pull the rope. Latané et al. (1979) suggested that the social impact theory could be used to explain social loafing. Decreases in individual motivation could be explained by the diffusion of responsibility among members (within a group) and a lack of confidence between them due to this diffusion; in collective tasks, participants would feel less responsible for group effectiveness (Ingham et al.; Latané et al.; Latané, 1986). Usually, these studies use a within-subject design that compares an individual’s performance in two different conditions (i.e., individual versus group or pseudogroup). In the group condition, participants are led to believe that they are performing a task as part of a group and that only the group’s performance is assessed. Then, experimenters compare the expected and actual group performances: A group’s expected performance is equal to the summation of each member’s individual performance achieved during the individual condition (first session), whereas actual performance is equal to the summation of each member’s individual 247 Jean-Philippe Heuze & Philippe C. Brunel performance achieved during the group (or pseudogroup) session. Authors also assess how individual performances evolve during the two conditions. G enerally, studies use mediumsized samples (about 50 participants) in a laboratory situation (cf. Karau & Williams, 1993). In the group context, collective performances are assessed by summation of individual performances. Social loafing is described as a robust group phenomenon, because it appears in various simple tasks which require physical effort such as rope-pulling (Ingham et al., 1974; Lichacz & Partington, 1996), shouting and clapping (e.g., C ohen, 1988 a; H ardy & Latané, 1986, 1988), tapping (H arcum & Badura, 1990), air pumping (Kerr & Bruun, 1983), swimming (e.g., Everett, Smith, & Williams, 1992), rowing (Anshel, 1995), running (Huddleston, Doody, & Ruder, 1985); or cognitive effort including brainstorming (e.g., C ooley, 1991; H arkins & Petty, 1982; H arkins & Szymanski, 1989; Williams & Karau, 1991), thought listing (Brickner, H arkins, & O strom, 1986), making causal attributions ( Q uintanar & Pryor, 1982), recalling information (Weldon, Blair, & Huebsch, 2000), and decision making (Henningsen, Cruz, & Miller, 2000). However social loafing also appears in tasks which require perceptual effort such as vigilance (H arkins & Petty, 1982; H arkins & Szymanski, 1989), tone counting ( G abrenya, Wang, & Latané, 1985), maze performance (e.g., G riffith, Fichman, & Moreland, 1989), finding items in a picture (Brickner & Wingard, 1988); or evaluative effort such as evaluating messages (Petty, H arkins, & Williams, 1980), writing materials (Petty, H arkins, Williams, & Latané, 1977), information (Price, 1987). However, interpersonal coordination tasks (in which participants have to coordinate their individual actions in order to obtain a collective outcome) seem more sensitive to this phenomenon than coactive ones (in which individual actions are added in order to obtain a collective outcome). Finally, although social loafing is not dependent on participants’ age and sex (H arkins, Latané, & Williams, 1980), or culture ( G abrenya, Latané, & Wang, 1983; G abrenya et al., 1985; Latané, 1986), its magnitude appears lower for women and participants from Eastern cultures ( G abrenya et al., 1985; Karau & Williams, 1993; Kugihara, 1999). N umerous studies have identified variables that are likely to influence the magnitude of social loafing (H ardy, 1990; H ardy & Crace, 1991; Karau & Williams, 1993; Williams, H arkins, & Latané, 1981; Williams, N ida, Baca, & Latané, 1989). First, at an individual level, the possibility of identification (Everett et al., 1992; Williams et al., 1981, 1989) and evaluation (H arkins, 1987; H arkins & Jackson, 1985; H arkins & Szymanski, 1988; Szymanski & H arkins, 1987) of individual performance, as well as task commitment can either decrease or even eradicate this phenomenon. G enerally, every factor allowing individuals to make a unique contribution to the group product reduces social loafing (H arkins & Petty, 1982). Moreover, individuals’ expectancies about their teammates’ performance influence loafing; participants loaf when they expect either good (H ardy & Crace, 1991) or even poor (Jackson & H arkins, 1985) performances from their teammates. Second, at a group level, an increase in group interactions, cohesion (Williams, 1981), collective efficacy (Lichacz & Partington, 1996), and attraction or group worth for members reduce the magnitude of social loafing. This phenomenon is also dependent on group size. An increase in group size induces a decrease in individual performance according to a curvilinear relationship (Ingham et al., 1974; Latané et al., 1979): the inclination of the curve is pronounced for small size groups (2-3 persons) and becomes flatter; above 6 persons, adding one person does not lead to a significant 248 Social Loafing in Sport decrease of individual performance. Third, task characteristics such as personal salience and incentive value (Brickner et al., 1986; Price , 1987; Shepperd & Wright, 1989), attractiveness (Zaccaro, 1984), difficulty (Bartis, Szymanski, & H arkins, 1988; H arkins & Petty, 1982; Jackson & Williams, 1985) also affect social loafing; persons do not loaf when the tasks contain these characteristics, even if they expect poor performances from their teammates (Williams & Karau, 1991). As this phenomenon is dependent upon motivational factors (e.g., G een, 1991; H ardy, 1990; Shepperd, 1993), research has focused on individual or group motivational variables having the potential to be involved in social loafing (Lichacz & Partington, 1996). For example, at an individual level, the dispositional factor of achievement orientation seems to interact with social loafing. Swain (1996) noted that high ego-oriented individuals (i.e., involved in social comparison of their performance with that of others) and low task-oriented individuals (i.e., involved in self-referenced development of ability) decreased their performance significantly within a group when individual outcomes were not identifiable. C onversely, when people are highly task-oriented and weakly ego-oriented, performances were not modified by the experimental conditions. At the group level, Lichacz and Partington (1996) showed that social loafing did not appear in groups when high collective efficacy was caused by positive performance feedback. Moreover, task salience combined with prior group history also had an effect on this phenomenon; social loafing did not appear when the participant performed a salient task with his/her regular teammate. However, other explanations have received greater attention from researchers; one of these is expectancy theory (Karau & Williams, 1993; Shepperd, 1993 ; Shepperd & Taylor, 1999). N akanishi (1988) noted that valence, expectancy, and instrumentality variables are useful to explain group motivational processes. These three variables were linked in the collective effort model developed by Karau and Williams (1993, 2001) after a meta-analysis was carried out on social loafing research. The purpose of this model was to understand individual performances on collective tasks. Within this model, social loafing is thought to result from low motivation arising when individuals perceive no value in contributing to a task, see no contingency between their contributions and achievement of a desirable outcome, and perceive the cost of contributing to be excessive (Shepperd, 1993). Some studies have investigated the relationships between social loafing and expectations of teammates’ levels of effort or performance. Jackson and H arkins (1985) found that participants matched their own efforts according to their expectations of coworkers’ levels of effort, whether their individual performance was identifiable or not. Williams and Karau (1991) also observed that participants worked harder collectively than individually when they expected their coworkers to perform poorly on a meaningful task. All these studies underline the importance of social loafing and show it to be robust group phenomenon. Therefore, it could be assumed that social loafing exists in team sports and must be taken into account by sport psychologists (H ardy, 1990). But results of past studies cannot easily be generalized to sport context due to some methodological problems. For example, experimental designs used experimental groups and 249 Jean-Philippe Heuze & Philippe C. Brunel not regular sport groups. However, Lichacz and Partington (1996) showed that individuals’ experience in the same group influenced social loafing: this phenomenon appeared with lower magnitude when persons performed collective tasks for a certain duration of time. Moreover, competition, which represents a major variable in sport situations, was not taken into account by researchers in their experimental procedures. O ver the last few decades, only one study has taken this variable into account; H ardy and Latané (1988) investigated social loafing under competitive conditions (i.e., individual competition, team competition, and no competition). They found a loafing effect when cheerleaders thought they were competing in a group; however competition by itself did not affect performance. To explain the lack of a competition effect on social loafing, the authors argued that the no-competition condition could have been perceived as implicit competition rather than a control condition. But another reason might be the cheerleaders’ expectancies which were not compared by the authors among the three competition conditions. In a recent study, Shepperd and Taylor (1999) found that participants worked hard when they perceived a contingency between individual performance and group performance. In H ardy and Latané’s study (1988), even in the no-competition condition, participants might perceive a contingency between individual and group performances, and therefore cheered hard. However, despite their results, H ardy and Latané (1988, p. 113) proposed that “competitive motives … may in future studies prove to moderate social loafing.” Based on this suggestion and on the expectancy theory, the purpose of the present study was to understand the influence of competitive context on social loafing. The competitive situation was manipulated so that a team had to compete against another of same or superior ability. It was proposed that in competition between two teams with similar or very close ability levels, participants would view the task (i.e., to win the game) as potentially achievable. Therefore, success would be expected by the athletes. The task would be perceived as more attractive and individuals would display optimum efforts that lead to good performances (Karau & Williams, 1993; N icholls, 1989; Shepperd, 1993). Hence, it was predicted that social loafing would not appear in such competitive context. C onversely, if two groups with clearly differing ability levels are competing, the team with inferior ability should perceive the task to be too difficult. Therefore, defeat would be expected by the athletes. Thus, the task would be perceived to be less attractive and the athletes would reduce their effort and consequently perform worse. Therefore, it was predicted that social loafing would be encountered in such competitive context. METHOD PARTICIPANTS Participants were 50 male freshmen from the Faculty of Sport Sciences at the University of Reims. Their average age was 20.18 ± 1.25 years. All students volunteered to participate. All participants competed at the regional or national level in various individual or team sports in private sports clubs for 8 years (average 8.13 ± 3.28). Furthermore, all of them had former team sport experience; they participated in soccer or volleyball classes during the first semester, before performing the experimental task. The choice of such a sample was due to two major reasons. First, the participants were accustomed to competition and perceived the competitive situation as meaningful. Second, it 250 Social Loafing in Sport was important to insure that ability levels of each experimental group were initially similar so that outcome expectancies would be due to competition against an opponent rather than low skill levels within the group. DESIGN AND PROCEDURE In order to understand the possible influence of competitive context on social loafing, we chose a typical experimental design generally used in social loafing studies. Each participant was requested to perform a four-round series on a dart throw task, without any time limit, during two different experimental sessions spaced one week apart. A round consisted of a three-dart throw. Between each round, the experimenter noted the score and gave the 3 darts back to the participant. Performance was calculated in the following way: 15 points for the bull’s-eye, 10 points for the first black and yellow circles, and then 9 points to 1 point respectively for each following circle on the dartboard. The maximum score was 180 (i.e., 4 rounds of 3 darts with a maximum of 15 points per dart). According to the international standard, the dartboard was set up at 2.34 m ahead of the throwing line; the inner bull’s-eye was at 1.72m above the floor. Prior to both sessions, athletes were allowed to familiarize themselves with the task, throwing a single round (i.e., 3 darts thrown one after the other). For the first session, participants performed the task individually. They were asked to focus on their own throws and to do their best performance, that is to get the highest total score. After each experimental round, each player was kept informed about the score of each dart. Also, after each four-round series, each participant was kept informed about his final score; the experimenter added the scores of the 12-dart throw together. For the second session, participants were randomly assigned to one of the five following groups. Each group contained 10 athletes and was tested separately. The C ontrol G roup was used to monitor individual improvement resulting from a repeated measure design. Athletes in the control condition performed the task under the same conditions as those used during the first session (i.e., throws were individually carried out and scored). The four experimental groups were as follows. A N o C ompetition G roup, which corresponded to a no-competition condition, was characterized by the absence of any fictitious opponents. The purpose of this condition was to see whether social loafing could appear during this experimental task. The remaining three group conditions were characterized by a dart contest against fictitious competitors. Participants were led to believe that they faced opponents who had already performed the task and had reached a specific score. The supposed opponents were of three types: C ompetition Same (competed against opponents with an identical score), C ompetition Inferior (competed a g ainst opponents with a score 10% gre ater), and C ompetition Superior (competed against opponents with a score 40% greater). To determine the opponents’ specific scores, individual results of each three previous experimental groups were added. Then, 0, 10 or 40% were added to the obtained results. These percentages were chosen in order to distinguish same, similar, and very different performance levels. 251 Jean-Philippe Heuze & Philippe C. Brunel Social Loafing in Sport For the four experimental groups, competitors were led to believe that only the overall group performance would be calculated, not their individual one. In fact, however, the experimenter computed individual scores surreptitiously. Each group was informed about its final score after all 10 members had completed the task. During the second session, all players from a group attended in the experimental room. They each did all their throws in turn, in an order defined at random (i.e., by drawing of lots). Participants in the N o C ompetition G roup were asked to focus on their own throws and perform the best collective performance they could do (they had no opponent). For the three other groups, members were asked to focus on their own throws and perform the best collective performance they could do in order to beat their opponents. But before completion of the session, each group was kept informed about its own performance and that of its opponents. Then, each member was asked to individually estimate the final score of his team after a talk amongst teammates. The instruction was: “You can talk about the final score of your team amongst teammates, but you have to note your individual estimation on the answer sheet.” Thus, the experimental design included three independent variables: group (control, no competition, competition same, competition inferior, competition superior), session (individual vs. collective), and outcome expectation (expected score was converted into expected success vs. expected defeat; no tied score was expected). RESULTS Session 1 M SD Session 2 M SD p Loafing index N o C ompetition G roup (n = 10) 87.90 10.74 81.60 12.39 .034 93 C ompetition Same G roup (n = 10) 87.40 9.66 93.80 10.36 .045 107 C ompetition Inferior G roup (n = 10) 87.30 5.44 88.30 9.07 ns 101 C ompetition Superior G roup (n = 10) 87.40 6.82 81.80 10.08 .047 94 C ontrol G roup (n = 10) 83.70 12.28 84.00 13.02 ns — N ote. ns: not significant. For N o C ompetition, C ompetition Same, C ompetition Inferior, and C ompetition Superior G roups, a loafing index was calculated (Latané, 1986; Lichacz & Partington, 1996); it was derived from the sums of the respective individual scores during the two sessions. Loafing index: (sum of individual scores during the 2nd session ÷ sum of individual scores during the 1st session) x 100. An index lower than 100 indicated a manifestation of social loafing (see Table 1). The first A N O VA showed a significant interaction, F(4,45) = 3.54, p < .02, ! = .24, power = .83. Table 1 presents the results of the within-group comparison of individual performances during the two sessions. A significant decrease in performances was observed in N o C ompetition G roup ( p < .05) and C ompetition Superior G roup ( p < .05) for the second session (see Figure 1). It appeared that when participants had to perform with teammates, their own performance decreased when they faced high level opponents (loafing index = 94) as well as no opponent (loafing index = 93). C onversely, C ompetition Same G roup’s performances increased significantly during the second session ( p < .05) (see Figure 1 again). This illustrates the fact that when individuals competed against opponents with the same supposed level, they increased their scores (loafing index = 107). 2 890 880 Session 1 870 Group performences Two A N O VAs with repeated measures and Scheffé post hoc comparisons were performed. The first 5 X 2 ( G roup by Session) A N O VA was carried out to test interaction effects between group and session on dart throwing performances. The second 2 X 2 (Estimate by Session) A N O VA was carried out to test the interaction effect between estimate (success vs. defeat) and session on dart scores. 252 Table 1 Within-group comparison of their performances during the two sessions. Session 2 860 850 840 830 820 800 780 760 740 NCG CSa G CI G CSu G CG Groups Figure 1. G roup performances during the two sessions. N ote. N C G : N o C ompetition G roup; CSa G : C ompetition Same G roup; CI G : C ompetition Inferior G roup; CSu G : C ompetition Superior G roup; C G : C ontrol group. 253 Jean-Philippe Heuze & Philippe C. Brunel Social Loafing in Sport Table 2 summarizes the between-group comparisons for each session. In the second session, significant differences emerged between the C ompetition Same G roup and both the N o C ompetition and C ompetition Superior G roups ( p < .05). Specifically, the scores for the C ompetition Same G roup were significantly higher than those of N o C ompetition and C ompetition Superior G roups during the second session. 96 94 Success Defeat Table 2 Between-group comparisons for each session. Session 1 NCG M SD NCG 87.90 10.74 Csa G 87.40 9.66 CI G 87.30 5.44 Csu G 87.40 6.82 CG 83.70 12.28 Session 2 SD NCG 81.60 12.39 Csa G 93.80 10.36 CI G 88.30 9.07 Csu G 81.80 10.08 CG 84.00 13.02 CI G CSu G CG ns ns ns ns ns ns ns ns ns ns CSa G CI G CSu G CG 88 86 84 82 80 76 Session 1 .028 ns ns ns ns .017 ns ns ns ns Note. ns: not significant; N C G : N o C ompetition G roup; CSa G : C ompetition Same G roup; CI G : C ompetition Inferior G roup; CSu G : C ompetition Superior G roup; C G : C ontrol group. A significant interaction between players’ estimates (success vs. defeat) and sessions on dart scores was observed, F(1,28) = 16.03, p < .001, !2 = .36, power = .97. Table 3 shows that participants who expected their group to be successful increased their individual performances significantly ( p < .01) during the second session (see Figure 2). C onversely, participants who expected their group to be defeated decreased their individual performances significantly ( p < .05) (see Figure 2). The between-group comparisons showed that, during the second session, performances were significantly higher in the group where individuals expected a success from their group than in the other group, where participants expected a defeat from their group ( p < .01). 254 90 78 NCG M CSa G Individual performances 92 Session 2 Sessions Figure 2. Interaction between players’ estimates and sessions. N ote. Success: expectation of success; Defeat: expectation of defeat. Table 3 Between and within comparisons of participants’ individual performances according to their estimates. Session 1 “Success” group (n = 16) “Defeat” group (n = 14) p Session 2 p M SD M SD 87.37 87.36 8.26 6.21 93.31 81.86 9.33 9.01 ns .008 .02 .002 N ote. ns: not significant. 255 Jean-Philippe Heuze & Philippe C. Brunel DISCUSSION The main objective of the present study was to understand the influence of competitive context on social loafing according to opponents’ levels. It was expected that social loafing would appear when participants faced high-level opponents, and that this phenomenon would not appear when teammates faced same-level opponents. Results of the control group in both sessions did not differ significantly indicating that there was no learning effect. Therefore, performance variations of the other groups could be considered to depend upon the experimental manipulations. The experimental condition for N o C ompetition G roup corresponded to the typical experimental design generally used in social loafing research. Indeed, it was aimed at understanding whether social loafing could appear during this additive task (Steiner, 1972) in which the group output is determined by summing individual outputs. In the second session, the significant decrease in individual performances of N o C ompetition G roup’s members emphasized similarly the social loafing phenomenon, just as previous studies had done (see H ardy, 1990 or Karau & Williams, 1993, for a review). As the dart throwing task was favorable to social loafing and as no learning effect was found, performance variations observed for C ompetition Same and C ompetition Superior G roups can be considered to be due to intergroup competition. Improvement of C ompetition Same G roup’s individual performances, decrease in C ompetition Superior G roup’s individual performances, and the lack of significant evolution for C ompetition Inferior G roup showed that the competitive context impacted on social loafing. As expected, this phenomenon occurred in C ompetition Superior G roup when opposed to a much higher level of opponent (i.e., group performance > 40%). For this group, we found a loafing index (94) similar to that of N o C ompetition G roup (93). However, indexes of these two groups are larger than those reported in prior studies: for example, in 6 or more person groups, individual performances decreased between 18% (Ingham et al., 1974) and 60% (Latané et al., 1979) on average; that is, indexes are between 82 and 40. The additive nature of the task can explain the lower magnitude of social loafing observed in this study insofar as individual performances remained identifiable (i.e., each participant could memorize his score for each dart thrown and add them together). But, as expected, this phenomenon disappeared when two sport groups competed against each other with the same level (e.g., C ompetition Same G roup), or with close level (e.g., C ompetition Inferior G roup); moreover, an opposite effect to social loafing was observed in C ompetition Same G roup. Therefore, intergroup competition seems to block the social loafing process when group performance levels are identical or similar. These results show that interpersonal competition not only moderates social loafing, as hypothesized by H ardy and Latané (1988), but also induces social loafing when it seems onesided. Different explanations can be suggested to understand the effect of intergroup competition on social loafing; some of them refer to perceptions of collective efficacy and task attractiveness. These variables are not controlled in the present study, but Lichacz and Partington (1996) observed social loafing in groups where they induced a low perception of collective efficacy. Perhaps, C ompetition Superior G roup members perceived performance differences between their group and their opponents as an index of low collective efficacy; these perceptions would explain the significant decrease in individual performances. C onversely, the lack of differences 256 Social Loafing in Sport between C ompetition Same G roup and its opponents could have induced a high perception of collective efficacy that promoted improvement in individual performances. Moreover, some studies have shown that task attractiveness has an influence on social loafing (Brickner et al., 1986; Price, 1987; Shepperd & Wright, 1989). C ompeting against a stronger opponent can appear to be unattractive for some participants. As for the members’ estimates, results showed that those who expected their team to win increased their individual performances in a group context. But an opposite reaction was found for members who expected their team to lose; a significant decrease in individual performances was observed for the second session. Results indicated that team performance expectations have an influence on the social loafing phenomenon; in the present study, they facilitated the expression of the phenomenon when group defeat was expected, or even produced an opposite effect when group success was expected. The collective effort model suggested by Karau and Williams (1993, 2001) may help us to understand this result. Karau and Williams’ model explains individual performance on collective tasks linking together the concepts of expectancy, instrumentality, and valence of the outcome. The combination of these three variables determines the motivational force which, in turn, determines the intensity and the duration of each person’s effort. When a member expects a team success (positive expectation), he /she might consider it important to display a high level of performance to concur with his/her team expectation, especially when the adversary’s level is identical or similar. Thus, the instrumentality level would be high (i.e., high quality performance is perceived as instrumental in obtaining the outcome). However, as the task is additive, the member might believe that reaching this performance level depends on his/her level of effort on the task. This kind of expectation combined with a high instrumentality level would produce an important motivational force for performing the task, and lead to an improvement in individual performances. C onversely, when an opponent’s performance level is much higher, members might think that their team is unable to win whatever the quality of their performances. This model considers that “individuals behave hedonistically and try to maximize the expected utility of their actions” (Karau & Williams, 1993 p. 684). As the performance quality would not allow members to win the competition, they might consider that displaying a high level of effort is useless. Moreover, competition took place in an experimental situation therefore, the valence of the outcome might be low. The combination of expectancy, instrumentality, and valence of the outcome might generate a low intensity motivational force for the task. However, if intergroup competition and team performance expectations influence social loafing, our experimental procedure does not clarify the direction of relationships between competition and expectations. For example, does competition influence social loafing directly or do team performance expectations represent mediators of the competition-social loafing relationship? O ur study shows that intergroup competition might, at the same time, both induce and reduce the social loafing. This variable has different effects on social loafing according to its modalities (e.g., same, close, much higher level of opponent ability). Thus, results observed in prior studies do not have to be directly extended to team sports, because these studies did not take into account this important variable. Further research is needed as the results of the present study were obtained using fictitious competition; the opponent’s a bility was 257 Jean-Philippe Heuze & Philippe C. Brunel manipulated through a score given by the experimenter. Moreover, the task did not require motor interactions between members. Studying social loafing in team sports requires procedures very similar to the real situations faced by teams. These procedures must contain competitions between real teams (Lichacz & Partington, 1996) on interactive tasks. It is also important to note that in this study only 24% (1st A N O VA) and 36% (2nd A N O VA) of the total variance can be explained by the treatment effects. The effect sizes and the power analyses indicate that the effects are moderate (C ohen, 1988b). As other factors, unidentified in this study, are at work, results reported here need other confirmations for a better explanation of the role of intergroup competition in the social loafing phenomenon. Finally, the procedure of this study cannot estimate the direction of relationships between intergroup competition, expectations, and social loafing. O ther studies with large samples are needed in order to use structural equation models and to find causal relationships between these variables. The previous remarks may question the usefulness of a laboratory study rather than real complex sport situations. O ne answer is that social loafing is not easy to measure in team sports. Individual performances are difficult to assess validly; they depend on the balance of power between each player and his/her opponent who, both, interact with their teammates and others opponents. Moreover, these performances are produced in competitive contexts where teams play against opponents with various ability levels. In the present experimental design, group ability levels could be controlled, and individual performances could be assessed. So, this research was a necessary first step in order to understand whether intergroup competition is an important factor in the social loafing phenomenon. Because generally, psychological laboratory studies produce truths rather than trivialities (Anderson, Lindsay, & Bushman, 1999), and research is an ongoing process based on both laboratory and field procedures, the results described here suggest that the study of this variable in real sport situations would be of great interest and could replicate or produce different results. Social Loafing in Sport allowing them to manipulate the ambiguity of an evaluation created by the competitive context in which they were engaged. Berglas and Jones (1978) used the term “self-handicap” to characterize the strategic creation of barriers that individuals place in the way during their own performance. Although the use of self-handicapping strategies increases the probability of a poor performance, they enhance nevertheless the opportunity to externalize a negative result and thus to protect self-esteem. According to Berglas and Jones (1978, p. 406), such strategies are defined as “any action or choice of performance settings that enhances the opportunity to externalize (or excuse) failure and to internalize (reasonably accept credit for) success.” In a social comparison context, as soon as the environmental information indicates a lower level of competence such as a clearly stronger opponent, individuals can engage in a voluntary reduction of their effort so as to preserve a favorable image of themselves. This strategy can similarly be used as those displayed by an individual who preserves himself/herself from the negative consequences of an anticipated failure explaining that it is not a good day for him /her or that he /she is injured (Pyszczynski & G reenberg, 1986). Thereby, in a group context, athletes have the opportunity to attribute their own failure, to a lack of effort, but not to a lack of ability. Individuals will devalue the activity so as not to appear incompetent (Jagacinski & N icholls, 1990; Lewthwaite, 1990; Urdan, Midgley, & Anderman, 1998) and become progressively amotivated (Brunel & Treasure, 1998). CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH Understanding social loafing in team sports supposes to clarify the roles of some important variables: (a) opponents’ level of performance which might act on the instrumentality level of the collective effort model (for example, through the expectation of results), (b) players’ expectations about relationships between individual effort and group performance (these expectations can be linked to players’ perceptions of their roles in their team), (c) valence of the team outcome for players, and (d) dynamic within the team. The former three variables derive from Karau and Williams’ theoretical model (1993, 2001); this model represents a relevant framework in order to understand the variations of individual effort in collective situation. The last variable follows our clinical observations on the field where one of the authors works as a sport psychologist with sport teams; interactions between members might induce a group dynamics through social influences that would influence the three variables of the collective effort model. Moreover, as social loafing is dependent on motivational factors, another relevant framework in which to understand this phenomenon could be the concept of self-handicapping. In the present study, participants from C ompetition Superior G roup seemed to use strategies 258 259 Jean-Philippe Heuze & Philippe C. Brunel REFERENCES H ardy, C .J., & Crace, R.K. (1991). The effects of task structure and teammate competence on social loafing. Journal of S port & Exercise Psychology, 13, 372-381. Anderson, C .A., Lindsay, J.J., & Bushman, B.J. (1999). Research in the psychological laboratory: Truth or tirviality? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8, 3-9. H ardy, C .J., & Latané, B. (1986). Social loafing on a cheering task. Social Science, 71, 165172. Anshel, M.H. (1995). Examining social loafing among elite female rowers as a function of task duration and mood. Journal of S port Behavior, 18, 39-49. H ardy, C .J., & Latané, B. (1988). Social loafing in cheerleaders: Effects of team membership and competition. Journal of S port & Exercise Psychology, 10, 109-114. Bartis, S., Szymanski, K., & H arkins, S. G . (1988). Evaluation and performance: A two-edged knife. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14, 242-251. H arkins, S. G . (1987). Social loafing and social facilitation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 23, 1-18. Berglas, S., & Jones, E.E. (1978). Drug choice as self-handicapping in response to noncontingent success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36, 405-417. H arkins, S. G ., & Jackson, J.M. (1985). The role of evaluation in eliminating social loafing. Personality and Social Psychology, 11, 575-584. Brickner, M.A., H arkins, S. G ., & O strom, T.M. (1986). Effects of personal involvement: Thought-provoking implications for social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 763-769. H arkins, S. G ., Latané, B., & Williams, K.D. (1980). Social loafing: Allocating effort or taking it easy? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16, 457-465. Brickner, M.A., & Wingard, K. (1988). Social identity and self-motivation: Improvements in productivity. Unpublished manuscript. Akron, O H: University of Akron. Brunel, P. C ., & Treasure, D. C . (1998). Antecedent of amotivation in physical education: Influence of motivational climate, self-esteem and self-handicapping strategies. Journal of S port & Exercise Psychology, 20 , S26. C ohen, C .J. (1988 a). Social loafing and personality: The effects of individual differences on collective performance (Doctoral dissertation, Fordham University). Dissertation Abstracts International, 49, 1430B. C ohen, J. (1988b). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. C ooley, R.J. (1991). Adult children of alcoholics: Interpersonal trust and social compensation. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Toledo. 260 Social Loafing in Sport H arkins, S. G ., & Petty, R.E. (1982). Effects of task difficulty and task uniqueness on social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 1214-1229. H arkins, S. G ., & Szymanski, K. (1988). Social loafing and self-evaluation with an objective standard. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 24, 354-365. H arkins, S. G ., & Szymanski, K. (1989). Social loafing and group evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 934-941. Henningsen, D.D., Cruz, M. G ., & Miller, M.L. (2000). Role of social loafing in predeliberation decision making. Group Dynamics, 4, 168-175. Huddleston, S., Doody, S. G ., & Ruder, M.K. (1985). The effect of prior knowledge of the social lo afing phenomenon on perform ance in a group. International Journal of S port Psychology, 16, 176-182. Ingham, A., Levinger, G ., G raves, J., & Peckham, V. (1974). The Ringelmann effect: Studies of group size and group performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 371384. Everett, J.J., Smith, R.E., & Williams, K.D. (1992). Effects of team cohesion and identifiability on social lo afing in relay swimming perform ance. International Journal of S port Psychology, 23, 311-324. Jackson, J.M., & H arkins, S. G . (1985). Equity in effort: An explanation of the social loafing effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 1199-1206. G abrenya, W.K., Latané, B., & Wang, Y.E. (1983). Social loafing in cross-cultural perspective: C hinese on Taiwan. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 14, 368-384. Jackson, J.M., & Williams, K.D. (1985). Social loafing on difficult tasks: Working collectively can improve performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 937-942. G abrenya, W.K., Wang, Y.E., & Latané, B. (1985). Social loafing on an optimizing task: Crosscultural differences among C hinese and Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 16, 223-242. Jagacinski, C .M., & N icholls, J. G . (1990). Reducing effort to protect perceived ability: “They’d do it but I wouldn’t.” Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 15-21. G een, R. G ., (1991). Social motivation. Annual Review of Psychology, 42, 377-399. Karau, S.J., & Williams, K.D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 681-706. G riffith, T.L., Fichman, M., & Moreland, R.L. (1989). Social loafing and social facilitation: An empirical test of the cognitive-motivational model of performance. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 10, 253-271. Karau, S.J., & Williams, K.D. (2001). Understanding individual motivation in groups: The collective effort model. In M.E. Turner (Ed.), Groups at work: Theory and research. Applied social research (pp. 113-141). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. H arcum, E.R., & Badura, L.L. (1990). Social loafing as a response to an appraisal of appropriate effort. Journal of Psychology, 124, 629-637. Kerr, N.L., & Bruun, S. (1983). The dispensability of member effort and group motivation losses: Free rider effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 78-94. H ardy, C .J. (1990). Social loafing: Motivational losses in collective performance. International Journal of S port Psychology, 21, 305-327. Kravitz, D.A., & Martin, B. (1986). Ringelmann rediscovered: The original article. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 936-941. 261 Jean-Philippe Heuze & Philippe C. Brunel Kugihara, N. (1999). G ender and social loafing in Japan. Journal of Social Psychology, 139, 516-526. Latané, B. (1986). Responsibility and effort in organizations. In P. G oodman (Ed.), Groups and organizations (pp. 277-303). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Latané, B., Williams, K.D., & H arkins, S. G . (1979). Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 822-832. Lewthwaite, R. (1990). Threat perception in competitive trait-anxiety: The endangerment of important goals. Journal of S port & Exercise Psychology, 12, 280-300. Lichacz, F.M., & Partington, J.T. (1996). C ollective efficacy and true group performance. International Journal of S port Psychology, 27, 146-158. N akanishi, M. (1988). G roup motivation and group task performance: The expectancyvalence theory approach. Small Group Behavior, 19, 35-55. N icholls, J. G . (1989). The competitive ethos and the democratic education. C ambridge, MA: H arvard University Press. Petty, R.E., H arkins, S. G ., & Williams, K.D. (1980). The effects of diffusion of cognitive effort on attitudes: An information processing view. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 81-92. Petty, R.E., H arkins, S. G ., Williams, K.D., & Latané, B. (1977). The effects of group size on cognitive effort and evaluation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 3, 579-582. Social Loafing in Sport Urdan, T., Midgley, C ., & Anderman, E.M. (1998). The role of classroom goal structure in student’s use of self-handicapping strategies. American Educational Research Journal, 35, 101-122. Weldon, M.S., Blair, C ., & Huebsch, D. (2000). G roup remembering: Does social loafing underlie collaborative inhibition? Journal of Experimental Psychology-Learning, Memory and Cognition, 26, 1568-1577. Williams, K.D. (1981, May). The effects of group cohesiveness on social loafing. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Psychological Association, Detroit. Williams, K.D., H arkins, S. G ., & Latané, B. (1981). Identifiability as a deterrent to social loafing: Two cheering experiments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 301311. Williams, K.D., & Karau, S.J. (1991). Social loafing and social compensation: The effects of expectations of co-worker performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 570-581. Williams, K.D., N ida, S.A., Baca, L.D., & Latané, B. (1989). Social loafing and swimming: Effects of identifiability on individual and relay performance of intercollegiate swimmers. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 10, 73-81. Zaccaro, R. (1984). Social loafing: The role of task attractiveness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 10, 99-106. Price, K.H. (1987). Decision responsibility, task responsibility, identifiability, and social loafing. O rganizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 40, 330-345. Pyszczynski, T., & G reenberg, J. (1986). Determinant of reduction of intended effort as strategy for coping with anticipated failure. Journal of Research in Personality, 17, 412-422. Q uintanar, L.R., & Pryor, J.B. (1982, August). Group diffusion of cognitive effort as a determinant of attribution. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Washington, D C . Ringelmann, M. (1913). Recherches sur les moteurs animés: Travail de l’homme. Annales de l’Institut N ational Agronomique, XII, 1-40. Shepperd, J.A. (1993). Productivity loss in performance groups: A motivational analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 67-81. Shepperd, J.A., & Taylor, K.M. (1999). Social loafing and expectancy-value theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 1147-1158. Shepperd, J.A., & Wright, R.A. (1989). Individual contributions to a collective effort: An incentive analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15, 141-149. Steiner, I.D. (1972). G roup processes and group productivity. N ew York: Academic. Swain, A. (1996). Social loafing and identifiability: The mediating role of achievement goal orientations. Research Q uarterly for Exercise and S port, 67, 337-344. 262 Szymanski, K., & H arkins, S. G . (1987). Social loafing and self-evaluation with a social standard. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 891-897. N ote Triplett, N. (1897). The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. American Journal of Psychology, 9, 507-533. The authors would like to thank Albert V. C arron for his comments and suggestions on this manuscript. 263