Full Text - ASU Digital Repository

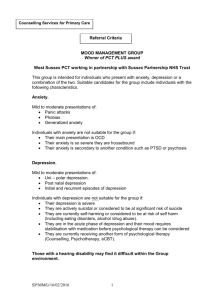

advertisement