Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity:

advertisement

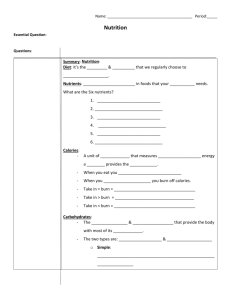

Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us May 2011 NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 1 Contents Key points ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 Background.......................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ....................................................................................................................... 4 Datasets ........................................................................................................................... 4 Interpretation of the data.............................................................................................. 6 Section one: adults .............................................................................................................. 7 a. Knowledge, beliefs and self-perceptions relating to diet........................................ 7 i. Knowledge of what constitutes a healthy diet and perceptions of information provision ..................................................................................................................... 7 ii. Appraisal of own diet ............................................................................................ 9 iii. Attitudes to healthy eating ................................................................................ 11 iv. Confidence in changing diet............................................................................... 11 v. Barriers to healthy eating .................................................................................... 11 vi. Facilitators of healthy eating.............................................................................. 13 b. Perceptions of dieting and weight loss ................................................................... 14 i. Weight, weight loss and dieting .......................................................................... 14 ii Factors influencing eating habits ......................................................................... 15 c. Knowledge, beliefs and self-perceptions relating to physical activity................... 16 i. Knowledge of recommended levels of physical activity..................................... 16 ii. Perceptions of physical activity facilities............................................................. 17 iii. Appraisal of own participation in physical activity ........................................... 17 iv. Barriers and facilitators to participating in physical activity ............................ 18 Section two: children and young people ......................................................................... 20 a. Knowledge, beliefs and self-perceptions relating to diet...................................... 20 i. Knowledge and understanding of what constitutes a healthy diet .................. 20 ii. Factors influencing healthy eating in school...................................................... 22 b. Perceptions of weight, weight loss and dieting ..................................................... 23 i. Weight, weight loss and dieting .......................................................................... 23 c. Knowledge, beliefs and self-perceptions relating to physical activity................... 24 i. Knowledge of recommended levels of physical activity..................................... 24 ii. Perceptions of physical activity facilities............................................................. 25 iii. Appraisal of own participation in physical activity ........................................... 25 Discussion and conclusions................................................................................................ 25 Appendix 1: glossary of terms .......................................................................................... 27 Appendix 2: summary of data sources and availability................................................... 29 Appendix 3: data tables .................................................................................................... 33 References.......................................................................................................................... 37 Since this report was researched and compiled, the Foods Standards Agency (FSA) released a report ‘An insight into attitudes to food’. Readers may find it helpful to also look at the FSA report. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 2 Key points • The majority of adults and children have an understanding of what constitutes a healthy diet. Eating lots of fruit and vegetables is the most frequently cited component of a healthy diet. • The majority of adults consider healthy eating to be important and would like to improve their own eating habits and those of their children. • Adults from lower income groups are more likely to cite cost as an important influence on their eating habits. • The most frequently cited method of controlling weight is trying to eat less at mealtimes. • The majority of adults report that they are either fairly or very physically active. Morbidly obese adults are significantly less likely than adults of a healthy weight to consider themselves physically active. • Time is the most commonly cited barrier to participation in physical activity. • The majority of children consider themselves to be about the right weight. • Incentives may be successful in encouraging children to make healthier food choices at school. • Interventions focusing on personal and social factors may be helpful in bringing about behaviour change. Introduction There is a range of data that describes people’s knowledge of and attitudes to physical activity and healthy eating in England. However, much of the data have not been examined in full and no attempt has been made to pull together the findings. The objective of this paper is to support public health practitioners who wish to gain a greater understanding of these issues. It presents new analyses of knowledge and attitudinal data on physical activity and dietary intake from national sources and investigates factors that may be mediators of behaviour change. Whilst it is recognised that there are additional data sources at local level and in the commercial sector, this paper is not intended to be a comprehensive review and only includes data which is in the public domain or freely available. The paper is split into two sections: adults and children. These sections are then further divided, where data is available, into the following themes: • knowledge, beliefs and self-perceptions relating to diet • perceptions of dieting and weight loss • knowledge, beliefs and self-perceptions relating to physical activity Background An individual’s diet and physical activity habits are influenced by their knowledge of and attitudes towards these behaviours. Investigation of these variables in a population provides an insight into the factors that may be mediators of motivation to change behaviour. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 3 Theories from health psychology, sociology and social psychology have been proposed to explain the link between knowledge, attitudes, skills, social and environmental influences, and behaviour. For example, the health belief model theorises that in order for behaviour change to take place, an individual must first believe that change is both possible and beneficial, and that the benefits of changing outweigh any perceived costs of making the change.1 The model demonstrates the relationship between an individual’s attitudes towards a particular set of behaviours, and their subsequent willingness or ability to make changes to improve or protect their health. For example, if a person does not consider their diet to be unhealthy, they are unlikely to make any significant dietary changes to improve their health – especially if they perceive that doing so would mean substituting food they like for food they may like less. Social cognitive theory also considers the importance of an individual’s knowledge and attitudes in influencing behaviour and behaviour change.2 In addition, it also recognises the impact of external factors such as social and environmental influences on individual behaviour.3 For example, the likelihood of a child eating five portions of fruit and vegetables a day will be influenced by social factors (e.g. their parents’ views on healthy eating), and environmental factors (e.g. the availability of fruit and vegetables at home). The principles of behaviour change theories have been used in research studies to identify personal and social correlates of healthy eating and physical activity behaviours. A systematic review identified that the perception of physical activity as being enjoyable was more highly correlated with participation than any health benefits.4 Other studies have, identified the physical environment as a determinant of physical activity – surroundings perceived as unpleasant or unsafe have been shown to act as a deterrent to physical activity participation.5 The influence of the social environment and, in particular, the views of peers and ‘significant others’ is a common theme as people tend to engage in behaviour which is practiced by, and valued by their peers. Self-efficacy, which is an individual’s belief that they are capable of changing their behaviours, can also be a key determinant of eating and physical activity behaviour. Researchers have recommended that motivational education techniques may be useful in influencing personal belief and therefore support sustained behaviour change.6 A review that looked at randomised, controlled psychological interventions for overweight or obese adults supports theories of behaviour change and advocates an approach to weight management that focuses on using cognitive therapies to change behaviour combined with healthy eating education and exercise components.7 Methodology Datasets This paper analyses national level data from a range of datasets on the knowledge of and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity of adults and children in England. The datasets used for the analyses are summarised in Figure 1 and described in more detail in Appendix 1. They were previously presented in a National Obesity Observatory (NOO) briefing paper, Data sources: knowledge of and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity.8 NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 4 The inclusion criteria used to select datasets in this and the earlier NOO briefing paper were: • the data were derived from questions which included those relating to knowledge, opinions, feelings, attitudes, beliefs and values regarding healthy eating or physical activity behaviours • the data were collected within the last ten years • the samples were robust at a national level The most recently available data were analysed from each data source. Data relating to actual dietary intake and physical activity levels were excluded. Body Mass Index (BMI) data were included where analysis across different weight categories was relevant. All datasets were in the public domain except for the Target Group Index (TGI) data. At the time of writing, TGI data were provided by the Department of Health (DH) for use by healthcare professionals and analysts up to the end of March 2011. Figure 1: dataset summaries Sample size (n) Raw data available Health Survey for England 2007 6,882 Yes Active People Survey 2008 180,000 Yes UK data archive Adults Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey 2005 3,728 Yes UK data archive Adults British Social Attitudes Survey 2008 4,486 Yes UK data archive Adults National Diet and Nutrition Survey 2000/01 2, 251 Yes UK data archive Adults Target Group Index 2008/09 20,000 Yes East Midlands Public Health Observatory on behalf of the DH Adults Food Standards Agency Consumer Attitudes Survey 2008 2,627 Yes Food Standards Agency Adults 543,713 No Published report Adults N/A No Published report Children 148, 988 No Published report Children Dataset Place Survey 2008 Sodexho School Meals and Lifestyles Survey 2005 Tell Us 3 Survey 2008 Data supply Target group Notes UK data archive Adults Questions which met the inclusion criteria were analysed at individual level. All of the data presented represent crude rates calculated from individual responses with 95% confidence intervals where appropriate and where sample sizes were provided. 7,504 Children Data not available for analysis NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 5 Interpretation of the data The data in this paper should be interpreted with caution and consideration given to potential bias due to sampling methodology and study design. Many of the included datasets were from surveys based on either self-completion questionnaires or interviews. Responses to single-choice and closed-list questions may provide a less accurate reflection of an individual’s views than an open-ended question, or a singlechoice question prioritised from a list. Self-report questionnaires about behaviours such as eating and physical activity are particularly prone to recall and reporting bias. The results may also be subject to response bias. This can occur when respondents are aware of specific behaviours being ‘socially desirable’ and are motivated to respond accordingly.8 This bias effect is more pronounced when a respondent is being interviewed. Where possible, 95% confidence intervals were included on all charts. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 6 Section one: adults This section summarises the responses given by adults regarding their physical activity and dietary intake as well as what they perceive constitutes a healthy diet in children. Key points • Most adults have an understanding of the different components of a healthy diet. Eating lots of fruit and vegetables is the most frequently cited component of a healthy diet. • The majority of adults consider healthy eating to be important, and their own diet to be healthy. • Obese and morbidly obese adults are significantly less likely to consider their diet to be very healthy and significantly more likely to report a desire to make healthy changes to their diet, than those of a healthy weight. • The majority of adults say they would like to make improvements to their own diets. Obese adults are significantly more likely than healthy weight adults to consider this difficult to achieve. • Difficulties in changing current eating habits, lack of time and the cost of healthy foods are the most frequently reported barriers to eating a healthier diet. • Adults from lower income groups are more likely than those from all income groups to cite affordability as a barrier to healthy eating. • The majority of respondents believe that schools have a responsibility to make sure children eat healthily and exercise regularly. a. Knowledge, beliefs and self-perceptions relating to diet The findings in this section are derived from a range of datasets. The main findings from these datasets have been categorised according to different themes: • knowledge of what constitutes a healthy diet and perceptions of information provision • appraisal of one’s own diet • attitudes to healthy eating • confidence in changing diet • barriers to and facilitators of healthy eating i. Knowledge of what constitutes a healthy diet and perceptions of information provision The results of the Health Survey for England 2007 (HSE 2007) suggest that the majority of adults were aware of the national public health campaigns relating to healthy eating including limiting salt intake, reducing fat intake and consuming at least five portions of fruit and vegetables per day. Respondents were presented with a list of possible components that could form part of a healthy diet for both adults and children. Multiple responses were allowed with no prioritisation between them. Over 90% of the respondents believed that the following were either ‘very important’ or ‘quite important’ for healthy diets in adults and children: NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 7 • limiting fat • limiting saturated fat • limiting sugar • eating lots of whole grain foods • eating lots of fruit and vegetables • limiting salt • drinking lots of water • eating a balanced diet There were a number of other interesting findings. Limiting fat was considered to be significantly more important for adults’ diets than children’s, while the reverse was true for the importance of limiting sugar. Eating lots of red meat was thought to be ‘not very important’ or ‘not at all important’ for the diets of adults (66%) or children (58%). Similarly, vitamin supplements were considered ‘not very’ or ‘not at all’ important for the diets of adults (68%) or children (67%). It should be noted, however, that it is not clear if the responses were affected by social desirability bias. The Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey 2005 (LIDNS 2005) recorded similar data to the HSE 2007 by asking adults: ‘What do you consider to be a healthy diet?’. Answers were free response, and eating more fruit and vegetables was mentioned most frequently with almost half of respondents citing this as a factor. Limiting fat intake was also mentioned by almost 25% of respondents. The top ten responses to this question are shown in Figure 2. Figure 2: Responses of adults from lower income groups to the question ‘What do you consider to be a healthy diet?’ More variety Eating regularly/not snacking Less sugar/sugary foods Eating smaller portions Using less fat in cooking Eating a balanced diet More fresh food Less fat/fatty foods More fruit/juice More vegetables 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% Source: LIDNS, 2005 NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 8 Responses to the two surveys varied according to question format. For example, only 6% of respondents mentioned ‘eating less sugar’ in the open-ended question from the LIDNS 2005, compared with over 90% of those provided with a closed-list question in the HSE 2007. The results may also have been influenced by the different timescales during which the data were collected. Limiting salt intake was not mentioned in the LIDNS 2005 survey, but was in the HSE 2007 survey. It is possible the benefits of reducing salt intake were more widely disseminated by the time the 2007 survey was carried out. The British Social Attitudes Survey 2008 (BSAS 2008) reports on adult perceptions of the quality of information about food and healthy eating for children. Almost 70% of respondents felt that schools should ensure that children eat healthily and exercise. Over 50% of respondents thought that the government should provide advice for parents, but only 35% stated that advice currently provided by the government for parents was useful. Data from the Target Group Index (TGI) provide information about people’s preferred source of information on healthy lifestyles. The majority of respondents (65%) said they would prefer to receive such information from their general practitioner or practice nurse. ii. Appraisal of own diet The HSE 2007 asked adults to assess their diet as either ‘very healthy’, ‘quite healthy’, ‘not very healthy’ or ‘very unhealthy’. The majority of respondents felt that their diet was ‘quite healthy’ and a significantly higher proportion said it was ‘very healthy’ than those who said it was ‘not very healthy’. Morbidly obese respondents were significantly less likely to believe that their diet was ‘very healthy’ than those of a healthy weight, although none reported that their diet was ‘very unhealthy’ (see Appendix 3, Table 1). In the same survey, 69% of respondents stated that they would like to eat more healthily. This suggests that although most people believe their diet to be healthy, there are still some aspects that they would like to improve. Those respondents classified as morbidly obese were significantly more likely to report that they would like to eat more healthily (81%) than those of a healthy weight (69%). The LIDNS 2005 also reported on the changes respondents would like to make to their own diet and that of their children. The question was open-ended. Eating more fruit and vegetables and eating a healthier diet were the most popular changes that people would like to make for themselves and for their children. Figures 3 and 4 show the top ten changes adults would like to make to their own and their children’s diet. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 9 Figure 3: Responses of adults to the question ‘What changes would you make to your own diet?’ Less sugar/other sugary foods Better quality foods Eat regularly/not snacking More organic food More variety More fresh food Less fat/fatty foods More vegetables (including salad) More fruit/fruit juice Healthier diet 0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% Source: LIDNS, 2005 Figure 4: Responses of adults to the question ‘What changes would you make to your children’s diet?’ Less fizzy/sugary drinks Less sugar/sugary foods Less crisps/chips Eat/drink more for other reasons More fresh food Less junk food More variety Less chocolate/sweets Healthier diet More fruit/fruit juice More vegetables (including salad) 0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% Source: LIDNS, 2005 NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 10 iii. Attitudes to healthy eating The Food Standards Agency’s (FSA) Consumer Attitudes Survey 2008 found that 87% of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement: ‘eating healthily is very important to me’. Healthy eating was also considered to be either ‘very important’ or ‘fairly important’ to 75% of adults in the LIDNS 2005. These data suggest that food, diet and healthy eating are considered to be important and relevant by the majority of people, although it is likely that these data may be subject to response bias. The HSE 2007 asked adults to state how strongly they agreed with six statements relating to their attitudes to healthy eating. Multiple responses could be selected from a list of options. The results showed that there were differences in attitudes between men and women. Significantly higher proportions of women than men believed that ‘healthy foods are enjoyable’ (80% and 66% respectively), and agreed that ‘I really care about what I eat’ (74% and 64% respectively). Conversely, a significantly higher proportion of men felt they ‘get confused over what’s supposed to be healthy and what isn’t’ (30% of men and 24% of women) and believed ‘if you do enough exercise you can eat whatever you like’ (20% of men and 14% of women). The HSE 2007 also found that 37% of people believed that ‘the tastiest foods are the ones that are bad for you’, with those with a BMI over 25 significantly more likely to agree with this statement than those with a BMI within the healthy range. This finding suggests that presenting healthy foods as an enjoyable option may increase the likelihood of them being selected, particularly among those in the higher BMI categories. The TGI survey also asked questions about people’s attitudes towards healthy eating, the responses to which are shown in Appendix 3, Table 2. The data show that people who were underweight were significantly less likely to consider their diet to be very healthy, and people who were obese were significantly more likely to consider that they ‘should do a lot more about their health’ compared with the whole sample. iv. Confidence in changing diet The HSE 2007 asked respondents how easy or difficult they would find it to make improvements to the way they eat. The majority of respondents (56.3%) believed that making improvements to their diet would be very easy or quite easy. This response was unaffected by weight status. However, respondents who were obese or morbidly obese were significantly more likely to report that they would find it difficult to make changes to their diet than those with a healthy weight. This finding suggests that successfully identifying and reducing barriers to change for these groups may have a positive impact on their diet. See Appendix 3, Table 3. v. Barriers to healthy eating Both the HSE 2007 and the LIDNS 2005 asked questions about barriers to improving eating habits. The HSE provided a list of 11 options including the categories ‘something else’ and ‘none of these’, from which respondents could choose all that applied. The most commonly reported barriers to healthy eating in the HSE 2007 were ‘it’s hard to change my eating habits’ (29%), ‘I don’t have enough time’ (27%) and ‘it costs too much’ (20%). NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 11 The LIDNS 2005 also asked respondents about barriers to making positive changes to their diet. The survey question provided a list of 21 options, from which respondents could choose all options that applied to them. The ten most frequently reported barriers are presented in Figure 5. Figure 5: Responses of adults to the question ‘What difficulties might you have with eating more healthily?’ Cooking skills I don't know enough about healthy eating Experts keep changing their minds Busy lifestyle Taste preferences of household members I don't want to change my eating habits No difficulty trying to eat healthier Lack of will power I don't want to give up foods that I like Price of healthy foods 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% Source LIDN, 2005 There are common themes apparent across the LIDNS 2005 and TGI surveys and, in particular, personal preferences for certain foods and concerns about cost. Results from the LIDNS 2005 indicate that the cost of healthy food is a greater barrier for lower income households. However, care must be taken in making comparison between these surveys due to their different methodologies. The TGI survey asked respondents what prevented them from living a healthier lifestyle. The most frequently reported responses were: • time • I already live a healthy lifestyle • other health problems I have • cost • lack of will power All responses are shown in Figure 6. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 12 Figure 6: Responses of adults to the question ‘What, if anything, prevents you from living a healthier lifestyle?’ Eating habits/eating the wrong foods Family influence/what family will do Access to facilities/healthier choices Other responsibilities/caring/ child care Can't be bothered Lack of will power Cost Other health problems I have I already live a healthy lifestyle Time 0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% Source: TGI, 2008/09 The TGI data showed significant differences across BMI categories (see Appendix 3, Table 4). Respondents who were obese or morbidly obese were significantly more likely to regard ‘other health problems I have’ as a barrier to a healthy lifestyle, and were significantly less likely to believe that their lifestyle was already healthy than the total sample. Obese respondents were also more likely to report ‘lack of will power’ and ‘can’t be bothered’ as barriers to a healthier lifestyle. vi. Facilitators of healthy eating Both the HSE 2007 and the LIDNS 2005 asked questions to identify what factors could support individuals to eat more healthily. The HSE 2007 asked respondents to choose as many factors as applied from a list of 12 options, including the categories ‘something else’ and ‘none of these’. The most frequently cited factors to were: • own ill health (48%) • being motivated (38%) • advice from a doctor or nurse (37%) The LIDNS 2005 asked people an open-response question about what factors would encourage them to change their diet. The most frequently cited factor was ‘more money/healthier food being less expensive’ (42%). See Figure 7 for the full results. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 13 Figure 7: Responses of adults to the questions ‘Are there things you would like to change about your current diet? and if so, ‘What would help you to make that change?’ Better shops in the local area Other support/encouragement Motivation/enthusiasm Better health (including teeth) Family members eating healthier food More time for shopping and food preparation Better information about food/healthy eating Other factors associated with attitude,skills, effort Will power/self‐discipline More money/healthier foood being less expensive 0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% 45% Source: LIDNS, 2005 b. Perceptions of dieting and weight loss This section summarises available data relating to: • weight, weight loss and dieting • factors influencing eating habits Key points • Approximately 15% of adults report that they are trying to lose weight. • The eating habits of obese and morbidly obese individuals are more influenced by emotional triggers than people of a healthy weight. • The most frequently cited method of controlling weight is trying to eat less at meal times. However, those who are obese and morbidly obese are significantly less likely than other groups to report this. • Being depressed and boredom are the most frequently cited emotional triggers for eating. i. Weight, weight loss and dieting Both the BSAS 2008 and the LIDNS 2005 provide data about dieting and weight loss. The BSAS 2008 reported that 15% of respondents were trying to lose weight. In the LIDNS 2005, 8% of people stated that slimming was one of the most important influences on their food choices. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 14 The National Diet and Nutrition Survey 2000/01 (NDNS 2000/01) also asked questions about attitudes towards weight and weight loss, eating patterns and emotional triggers for eating. Respondents were asked which scenarios applied to them and were given the options; ‘never’, ‘seldom’, ‘sometimes’, ‘often’ or ‘very often’. These data were analysed to identify significant differences in responses between the whole sample and the different BMI categories (‘underweight’, ‘healthy weight’, ‘overweight’, ‘obese’ and ‘morbidly obese’), and significant differences between those of a healthy weight and the other BMI categories. Individuals who were obese or morbidly obese were significantly more likely than the whole sample, or those of a healthy weight, to say that they ‘try to eat less at meal times than (they) would like’ either ‘often’ or ‘very often’. Individuals who were categorised as overweight or obese (but not morbidly obese) were significantly more likely than the whole sample and those of a healthy weight to say they ‘deliberately eat foods that are slimming’, ‘try not to eat between meals because [they] are watching [their] weight’ or ‘try not to eat in the evening’ either ‘often’ or ‘very often’. Overweight individuals (but not obese or morbidly obese individuals) were significantly more likely than the whole sample or those of a healthy weight to report that they ‘take [their] weight into account with what (they) eat’ either ‘often’ or ‘very often’. Individuals who were underweight or a healthy weight were significantly less likely than the whole sample to report that they ‘try not to eat between meals because [they] are watching [their] weight’ either ‘often’ or ‘very often’. ii Factors influencing eating habits Obese respondents from the NDNS 2000/01 were significantly less likely than healthy weight respondents to say that they ‘could resist eating delicious food’ either ‘often’ or ‘very often’. This group was also significantly more likely than the whole sample, or those of a healthy weight, to say that they have a desire to eat when: • they are irritated • they are depressed or discouraged • someone has let them down • they are worried, anxious or tense • things are going against them or have gone wrong • they are emotionally upset • they are bored • they are disappointed • they are lonely • they have nothing to do These data suggest that, compared with people of a healthy weight, the eating habits of obese and morbidly obese individuals are more influenced by emotional triggers. There were no significant differences in responses from individuals of a healthy weight and other BMI categories for the questions: • If food smells and looks good, do you eat more than usual? NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 15 • If you see or smell something delicious, do you have a desire to eat it? • If you have something delicious to eat, do you eat it straight away? • If you walk past a bakery, do you have the desire to buy something delicious? • If you see others eating, do you also want to eat? • Do you eat more than usual when you see others eating? • When preparing a meal, are you inclined to eat something? Underweight individuals, however, were significantly more likely than healthy weight individuals to state that they ‘have the desire to buy something delicious if [they] walk past a snack bar or cafe’ either ‘often’ or ‘very often’. This suggests that emotions tend to trigger a desire to eat more than sensory stimulus, regardless of an individual’s BMI status. c. Knowledge, beliefs and self-perceptions relating to physical activity This section summarises available data relating to: • knowledge of recommended levels of physical activity • perceptions of physical activity facilities • appraisal of own participation in physical activity • barriers and facilitators to participating in physical activity Key points • The majority of adults are aware that physical activity recommendations exist, but few know what they are. • 71% of adults consider themselves to be fairly or very physically active. • Morbidly obese adults are significantly less likely to consider themselves to be very physically active than those who are a healthy weight. • The most frequently cited reasons for taking part in physical activity are to maintain health and feel fit. • The majority of adults would like to take part in more physical activity than they do currently. • The most commonly cited activity that adults would like to do more of is swimming. • Time pressures and lack of motivation are the most commonly cited barriers to participating in physical activity. i. Knowledge of recommended levels of physical activity The HSE 2007 asked participants if they were aware of the recommended levels of physical activity. Three options were provided from which respondents could choose one, and 27.5% of adults said they knew what the recommended levels of activity were (see Appendix 3, Table 5). When asked what levels of physical activity adults of their age should take part in, only 6% of men and 9% of women thought people their age should do 30 minutes of physical activity at least five days of the week (equivalent NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 16 to the recommended levels of activity when the HSE 2007 survey was undertaken). A further 24% of adults specified that a higher level of physical activity than this should be undertaken. ii. Perceptions of physical activity facilities The Active People Survey 2008 (APS 2008) asked how satisfied participants were with sports facilities in their local area. Almost 60% said they were ‘fairly’ or ‘very satisfied’, whilst fewer than 15% felt ‘fairly’ or ‘very dissatisfied’. Figure 8 shows the range of responses. Figure 8: Responses of adults to the question ‘How satisfied are you with sports provision in your local area?’ 45% 40% 35% 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% Very dissatisfied Fairly dissatisfied Neither satisfied or dissatisfied Fairly satisfied Very satisfied No opinion/not stated Source: APS, 2008 The Place Survey provides some information about access to sports facilities, parks and open spaces. The data shows that the majority of respondents had used such facilities in the previous six months or year, with more respondents using parks and open spaces than sports facilities (see Appendix 3, Table 6). There is no data available about frequency of use. iii. Appraisal of own participation in physical activity The HSE 2007 asked participants how physically active they considered themselves to be compared to others of their own age.a Whilst the majority of adults (71%) considered themselves to be ‘fairly’ or ‘very’ physically active, the results varied according to gender and BMI. Respondents who were obese or morbidly obese were significantly more likely than those of a healthy weight to say they were either ‘not very’ or ‘not at all’ physically active (see Appendix 3, Table 7). Participants were also a ‘Physical activity’ was defined as: ‘A wide range of activities involving movement including housework such as vacuuming and digging the garden, active hobbies, walking and cycling, dancing, exercise such as swimming or going to the gym, and sport. It includes movement done as part of a job such as walking, lifting and carrying’. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 17 asked why they chose to take part in physical activity. The most commonly cited reasons were: • to maintain good health (61%) • to get or feel fit (52%) • to be outdoors (48%) • to lose or maintain weight (47%) The APS 2008 found that 51% of adults would like to do more sport and recreational physical activity, with swimming the most preferred sport (7%) followed by cycling (2.5%). The HSE 2007 had found that 67% of respondents would like to take part in more physical activity than they currently do. The APS 2008 also indicated how participation in physical activity changed over the course of a year. More than half of respondents (55%) reported doing about the same level of physical activity compared to the previous year; a quarter doing less than a year ago; and almost a fifth (19%) doing more. The results are shown in Figure 9. Figure 9: Responses of adults to the question ‘Do you generally do more, less or the same amount of sport and recreational physical activity as you did this time last year?’ 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Same Less More Source: APS, 2008 iv. Barriers and facilitators to participating in physical activity The HSE 2007 investigated perceived barriers to physical activity and the factors that would motivate participants to be more physically active. Participants were asked what prevents them from doing more physical activity, exercise or sport and provided with a list of practical barriers from which they could give multiple responses. The most frequently cited practical barriers were: • work commitments (38%) • lack of leisure time (37%) NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 18 • caring for children or older people (21%) • not having enough money (14%) Men were more likely to indicate work commitments as a barrier (45% compared with 33% of women), whilst women were more likely to indicate caring for children or older people (27% of women compared with 14% of men). 15% of respondents did not feel the need to do more physical activity. Participants were then asked what other factors prevent them from doing more physical activity, exercise or sport and were provided with a list of emotional and psychological barriers from which they could give multiple responses. ‘Lack of motivation’ was cited most frequently (29%), followed by not being the ‘sporty type’ and ‘having other things to do’. They were also asked what would encourage them to take part in more physical activity and the most commonly cited factors were: • more leisure time (49%) • increased motivation (40%) • own ill health (36%) • advice from a doctor or nurse (29%) NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 19 Section two: children and young people This section refers to data on children and young people. There are fewer sources of data available relating to children than adults. A range of age groups was sampled by the different surveys, and this may impact on responses. a. Knowledge, beliefs and self-perceptions relating to diet This section summarises available data relating to: • children and young people’s knowledge and understanding of what constitutes a healthy diet and appraisal of their own diet • factors influencing healthy eating in school Key points • The majority of children and young people consider their diet to be healthy. • When asked whether or not they have a healthy diet, children and young people tend to base their answer on their fruit and vegetable consumption. • 76% of children in school years 6, 8 and 10 say the information available to them about healthy eating is good enough. i. Knowledge and understanding of what constitutes a healthy diet The Sodexho School Meals and Lifestyles Survey 2005b asked a sample of children and young people aged 5 to 7 years and 8 to 16 years how healthy they believe their diets to be. The majority thought that their diet was ‘quite healthy’ (56% of 5 to 7 year olds; 54% of 8 to 16 year olds) or ‘very healthy’ (18% of 5 to 7 year olds; 16% of 8 to 16 year olds). In contrast, only 1% of 5 to 7 year olds and 2% of 8 to 16 year olds thought that their diets were ‘not at all healthy’. The largest difference between the age groups was seen in those who said their diets were ‘not very healthy’ (6% of 5 to 7 year olds and 18% of 8 to 16 year olds). These results are shown in Figure 10. b The data reported here are from the Sodexho report on the survey, where the number of respondents is not provided. Therefore it was not possible to calculate confidence intervals. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 20 Figure 10: Responses of children and young people to the question ‘How healthy do you think your diet is?’ 60% 5‐7 years 8‐16 years 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Very healthy Quite healthy Source: Sodexho School Meals and Lifestyle Survey, 2005 Not very healthy Not at all healthy ii The children and young people who described their diet as either ‘very healthy’ or ‘quite healthy’, were asked to explain their answer. They could give multiple answers from a list of 12 options. The most frequently cited answers were: • I eat a lot of fruit (63% of 5 to 7 year olds and 52% of 8 to 16 year olds) • I eat a lot of vegetables (46% of both age groups) • I eat a good balanced diet (16% of 5 to 7 year olds, 24% of 8 to 16 year olds) Only 12% of 5 to 7 year olds and 13% of 8 to 16 year olds selected eating low-fat foods, low-salt foods or eating less red meat. A small proportion of 5 to 7 year olds (3%) and 8 to 16 year olds (6%) said their diet was healthy because they ‘don’t eat sweets/chocolate’. The results are shown in Figure 11. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 21 Figure 11: Responses of children and young people to the question ‘Why do you think that your diet is very healthy/quite healthy?’ I eat low fat foods 8‐16 years I don’t eat sweets/chocolates 5‐7 years I don’t eat junk foods I eat salads I eat a variety of foods I eat good food I drink lots of water/juice I eat a good balanced diet I eat lots of vegetables I eat lots of fruit 0% 10% 20% Source: Sodexho School Meals and Lifestyle Survey, 2005 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% ii Further relevant data are available from the Tell Us 3 Survey 2008. It asked children and young people aged 10 to 16 (in school years 6, 8 and 10) for their views on the quality of information provided to them in school on healthy foods and lifestyles: • 76% said they thought the information and advice was ‘good enough’ • 20% said they ‘needed better information and advice’ • 4% ‘didn’t know’ ii. Factors influencing healthy eating in school The Sodexho School Meals and Lifestyles Survey 2005 asked children and young people aged 8 to 16 what factors might help them to make healthier food choices at school. They identified practical incentives that would help them to make healthier food choices and were able to select more than one option from a list of ten, making it difficult to show true preferences. The most popular choices were the opportunity to win prizes, less queuing time for healthy dishes and better choices of healthy dishes. The responses to this question are shown in Figure 12. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 22 Figure 12: Responses of children and young people aged 8–16 years to the question ‘What would help you to make healthier choices at school?’ Improved decoration and better seating Having more healthy items in the tuck shop/mid‐morning break Having vending machine service for healthy food Special days when you can sample healthy dishes Help yourself salad bar at lunchtime Wider range of prepared fruit available Cheaper prices for healthy options Better choice of healthy dishes Less queuing time for healthy dishes Opportunity to win prizes if you select healthy items 0% Source: Sodexho School Meals and Lifestyle Survey, 2005 10% 20% 30% 40% ii b. Perceptions of weight, weight loss and dieting This section summarises available data relating to children and young people’s perceptions of weight, weight loss and dieting. Key points • The majority of children and young people (73%) consider themselves to be about the right weight. • The majority of children and young people classified by the HSE 2007 as overweight (77.3%) consider themselves to be about the right weight as do 46.3% of children classified as obese. • 65% of children and young people classified as obese are trying to lose weight. i. Weight, weight loss and dieting The HSE 2007 provided information on children and young people’s perception of their own body weight and whether they were actively trying to lose weight. The majority (73%) aged 8 to 15 years felt that they were ‘about the right weight’, 16% ‘too heavy’ and 10% ‘too light’. These data were compared with the BMI category assigned to them (calculated from the anthropometrics recorded by nurses as part of the survey). The results show that 77.3% of those categorised as ‘overweight’ stated that they thought they were ‘about the right weight’ as did 46.3% of those NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 23 categorised as obese.c There was no category in the dataset for underweight children and young people, so it is likely that the sample of normal weight children and young people also included some who were underweight (See Appendix 3, Table 8). Of the same sample, 67.1% reported that they were not trying to change their weight; 26% were trying to lose weight; and 6.9% were trying to gain weight. Analysis of these data by BMI category indicates that, amongst children and young people classified as obese, 65.1% reported that they were ‘trying to lose weight’, whilst 34.3% were ‘not trying to lose weight’ (see Appendix 3, Table 9). Interestingly, 77.3% of those classified as overweight said they are ‘about the right weight’ and 60.5% were ‘not trying to change weight’. These findings indicate a potential area for intervention to ensure that this group do not become obese and do take action to become a healthy weight. c. Knowledge, beliefs and self-perceptions relating to physical activity This section summarises available data relating to: • knowledge of the recommended levels of physical activity • perceptions about local physical activity facilities • appraisal of own physical activity participation Key points • 32% of children and young people age 11–15 believe that people their own age should take part in physical activity every day of the week. • 37% of children and young people age 11–15 believe that people their own age should exercise for 60 minutes for it to be good for their health. • The most popular location for physical activity that children and young people in school years 6, 8 and 10 would like to visit which they do not already visit, is a gym. • Approximately half of children and young people in school years 6, 8 and 10 (aged 10 to 16) are satisfied with the physical activity facilities in their area. i. Knowledge of recommended levels of physical activity The Chief Medical Officer advises that children and young people should participate in a minimum of 60 minutes of at least moderate intensity physical activity each day. The HSE 2007 found that 32% of children and young people age 11–15 believed that people their own age should take part in physical activity every day of the week and that 37% believed that people their own age should exercise for 60 minutes for it to be good for their health. 11% of children and young people in this age group also believed both that young people should do physical activity seven days a week and that they should do it for 60 minutes to be good for their health. c The BMI categories used were those assigned by the Information Centre, contained in the raw dataset. Following the publication of the 2007 data, the Information Centre issued an errata note relating to their methodology for assigning overweight and obese categories to children. However, these data have been used in this analysis on the basis that this misclassification affected a small number of children and no cases were significantly different from the published data. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 24 ii. Perceptions of physical activity facilities Data from the Tell Us 3 survey 2008 reveals children and young people’s perceptions of the facilities in their local area: • 49% thought they were either ‘very good’ or ‘fairly good’ • 22% thought that they were ‘neither good nor poor’ • 26% thought they were either ‘poor’ or ’very poor’ The Tell Us 3 Survey 2008 asked children and young people what facilities they would like to go to (but had not already been to) to take part in physical activities. The most popular choices were the gym (38%) followed by swimming pools (29%) and a sports club or class (20%). iii. Appraisal of own participation in physical activity The HSE 2007 asked children and young people how active they would describe themselves to be compared with children of their own age. The majority of girls (85%) and boys (90%) aged 11–15 considered themselves to be fairly or very physically active. This is particularly important as there is some evidence that young people’s attitudes towards physical activity by the time they have completed secondary school is predictive of their physical activity levels as adults (see Appendix 3, Table 10).9 Discussion and conclusions The data show that diet, healthy eating and physical activity are important issues to people. Most people have an understanding of what constitutes a healthy diet and the majority of adults would like to improve their own eating habits and those of their children. Most children and young people consider themselves to be about the right weight and their diet to be healthy. People who are obese appear to experience particular difficulties in translating knowledge of healthy behaviour into practice. Whilst they are more interested in making healthy changes to their diet, they are also more likely to consider this difficult to achieve. In addition, they generally express a preference for less healthy foods and are less likely to consider themselves to be physically active. Health is highly prioritised as a motivating factor for both healthy eating and physical activity. However, a dislike of healthy foods by individuals and their families, the higher costs of these foods and a lack of willpower may prevent them from eating healthily. Similarly, time pressures and a lack of motivation may prevent people from taking part in physical activity. It is important to understand people’s attitudes and beliefs in order to plan targeted and appropriate interventions. For example, analysis of the LIDNS 2005 data suggests that promoting ways of making healthy meals quickly and cheaply is likely to be most effective among low-income groups as this would address the main barriers identified. Another study, which investigated people’s attitudes, concluded that motivation to participate in physical activity is correlated with perceptions of local surroundings.10 People are less motivated to be physically active if they perceive their local surroundings to be unsafe or unpleasant. This is a complex area of work in which much more research is needed to really understand how individuals can be motivated to make changes to their behaviour NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 25 that will improve their health. It is clear that knowledge of and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity are significant determinants of eating and activity behaviour. Knowledge and attitudes ultimately impact on weight status, and may be central to the success of behaviour change interventions. The data also suggests that there are significant differences in barriers and motivators between those who are obese and those who are not. There are a number of national data sources that provide useful, population level information about personal and social correlates of healthy eating and physical activity. Further analyses of the data, particularly from the HSE 2007, to investigate differences between reported dietary intake and physical activity levels of respondents against their attitudes, knowledge and perceptions of their own diet and physical activity levels would yield further useful insights. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has produced guidance for behaviour change interventions.11 This guidance supports the conclusions in the review and advocates a holistic approach that takes into account individual needs. The guidance describes a stepped approach to building behaviour change interventions including planning and design, delivery and evaluation. It discusses how interventions may be tailored to specific populations. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 26 Appendix 1: glossary of terms Attitude The way a person responds to people, concepts and events in an evaluative way. Behaviour The actions by which an individual adjusts to their environment. Belief Confidence or trust in a given opinion in the absence of rigorous proof. Body Mass Index (BMI) A measure of body mass calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in metres squared. The recognised categories for BMI are: BMI less than 18.5 – underweight BMI 18.6 – 24.9 – healthy weight BMI 25 – 29.9 – overweight BMI 30 – 39.9 – obese BMI 40 or more – morbidly obese Cognitive therapy A type of psychotherapeutic treatment that attempts to change feelings and behaviours by changing the way a person thinks about or perceives significant life experiences. Determinant A factor or circumstance that affects an outcome or behaviour. Emotion A complex pattern of changes, including physiological arousal, feelings, cognitive processes and behavioural reactions, made in response to a situation perceived to be personally significant. Incentives External stimuli or rewards that motivate behaviour. Motivation The process of starting, directing and maintaining physical and psychological activities. This includes mechanisms involved in preferences for one activity over another and the vigour and persistence of responses. Non-response bias Where results of a survey may be affected by particular groups of individuals choosing not to answer specific questions. Opinion A personal view, attitude or appraisal. Perception The process by which a person detects and interprets external stimuli. Response bias Where results of a survey may be affected by individuals, who are interested in the subject matter, being more likely to consent to take part. Sample bias Where the results of a survey may be affected by the use of a sample that is not representative of the population of concern. Self-efficacy The set of beliefs that one can perform adequately in a particular situation. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 27 Self-esteem A generalised evaluative attitude toward the self that influences both moods and behaviour and that exerts a powerful effect on a range of personal and social behaviours. Skill The ability to carry out a task effectively. Value An ideal or custom which is considered important. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 28 Appendix 2: summary of data sources and availability Health Survey for England12 The Health Survey for England (HSE) is an annual survey designed to measure health and health-related behaviours in adults and children living in private households in England. It has been undertaken since 1991. In recent years, sample sizes have typically been around 16,000. The survey consists of an interview and a nurse visit for a subsample. The HSE sample size is currently not sufficiently robust to enable analyses of data at geographical boundaries smaller than strategic health authority level. The HSE is modular but has a number of core elements which are included each year. Since 2001 these have included a number of dietary recall questions relating to fruit and vegetable consumption in the last 24 hours. The HSE 2007 had a focus on healthy lifestyles: knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. The total sample size for the 2007 survey was 14,386 of which 7,504 were children aged 0-15 due to a boost sample. 2007 is the only year in which specific questions relating to attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity have been asked, meaning that this data source is of limited use in terms of surveillance of attitudes over time. Raw data from the HSE 2007 has been accessed from the UK data archive at individual level. Information presented in this paper is, therefore, based on crude rates with no weightings applied. Active People Survey13 The Active People Survey (APS) is conducted by Sport England and aims to measure variance in adult participation in sport and physical activity. It also includes questions relating to what people feel about the amount of exercise they do and what they think of sports facilities in their area. The first APS was conducted between October 2005 and October 2006 and interviewed 363,724 people across England by telephone (approximately 1,000 in each local authority). The APS has been running annually. However, the total sample size has been halved to 500 per local authority (180,000 in total) with an opportunity for local authorities to fund boost samples for their own areas. This opportunity was taken up by 14 local authorities in the 2007/08 survey. Raw data from the APS 2008 has been accessed from the UK data archive at individual level. Information presented in this paper is, therefore, based on crude rates with no weightings applied. The Place Survey14 The Place Survey was conducted between September and December 2008 and explored people’s attitudes towards their local area, including access to health services and sports facilities. The questionnaires contained the same core questions nationally, although local authorities were able to add further questions from a central bank for use in their own locality. The Place Survey must be conducted by every local authority bi-annually, although individual local authorities may undertake it on an annual basis if they choose. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 29 The Place Survey was completed by a sample of 543,713 nationally, although sample sizes varied between local authorities. Measures were put in place to protect the quality of the data due to the surveys being carried out by local authorities independently, including guidance on sampling method and the use of an appropriate sampling frame. In addition, results were submitted centrally using standardised tools. Data from the Place Survey 2008 is taken from the further findings report published by the Audit Commission as no raw data was available for this dataset. Tell Us Survey15 Tell Us is a series of annual online surveys to gather quantitative information on the views and experiences of children and young people. It is commissioned by The Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (Ofsted) and the Department of Children, Schools and Families, and is carried out by Ipsos MORI. The surveys have been running since 2006 and are intended to provide evidence for the national indicators for local authorities and local authority partnerships. The survey aims to help local authorities judge the impact of their services on perceived quality of life for children and young people. Tell Us asks children and young people questions relating to the five Every Child Matters outcomes which include healthy eating. Children are asked attitude questions on their perceptions of the information and advice they get on eating healthy food. Tell Us is completed by a sample of children in all local authority areas across England. Pupils complete questionnaires online via a dedicated website. The sample size is calculated with a view to obtaining a sufficient number of responses to allow robust analysis at local area level. Sampling mechanisms take account of different types and sizes of schools together with socio-economic factors. The sample includes maintained schools, pupil referral units, academies and city technology colleges. Data are collected at school level, and aggregated up to local authority level. Data from Tell Us 3 is taken from the report published by Ofsted as no raw data were available for this dataset. Food Standards Agency Consumer Attitudes Survey16 The Food Standards Agency conducted the first Consumer Attitudes Survey in 2000 and it has since been conducted annually, with the exception of 2008 when it was reviewed. The survey includes questions exploring attitudes to food safety as well as towards cooking and healthy eating. The latest data from 2007 was collected using face-to-face interviews in participants’ homes. The total sample of 2,627 was stratified across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland making the data robust at country level. Data from ‘Wave 8’ of the survey was accessed at individual level directly from the Food Standards Agency. Information presented in this paper is, therefore, based on crude rates with no weightings applied. Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey17 The Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey (LIDNS) was commissioned by the FSA to provide nationally-representative evidence on food and nutrient intakes, sources of NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 30 nutrients and the nutritional status of people with a low income. An additional aim was to examine the relationship between dietary intake and factors associated with food choices in low-income populations. The survey was carried out by a consortium of three organisations and led by the Health Research Group at the National Centre for Social Research. The survey aimed to study 15% of the most materially deprived populations within the UK. A total of 3,728 people from 2,477 households were included in the survey, which took place between November 2003 and January 2005. The survey included adults (aged 19 and above) and children (aged 2-18). Information was collected in face-to-face interviews and self-completion questionnaires, and included environmental, economic and social factors. The LIDNS also gives information about how capable people feel about cooking and preparing food for themselves, and the impact this has on their food choices. Data from the LIDNS 2005 has been accessed from the UK data archive at individual level. Information presented in this paper is based on crude rates with no weightings applied. British Social Attitudes Survey18 The British Social Attitudes Survey (BSAS) has been conducted annually since 1983 with the exceptions of 1988 and 1992 when funding was diverted to the British Election Study (BES) following general elections. In 1997 a scaled-down version was conducted alongside the BES. The central aim of the BSAS is, as the name suggests, to examine attitudes towards various social, economic, political and moral issues, including sporting activities and physically active modes of transport. The National Centre for Social Research holds primary responsibility for the BSAS and use a combination of face-to-face interviews and self-completion questionnaires to collect data. A multi-stage stratified random sample of British adults (over 18) is conducted using the postcode address file: the total sample in 2007 being 4,124. Data from the BSAS 2008 has been accessed from the UK data archive at individual level. Information presented in this paper is based on crude rates with no weightings applied. Sodexho School Meals and Lifestyles Survey19 Sodexho are a private sector company providing various food services including school meals. In 1990 they began carrying out surveys on the types of food school children eat as well as their preferences and attitudes towards food and nutrition. The latest available survey data is from the 2005 survey and it included core questions as well as extra questions on intake of fruit and vegetables and water consumption. No information was available in the report on the size or demographics of the sample. Data from the Sodexho School Meals and Lifestyles Survey is taken from the report published by Sodexho as no raw data was available for this dataset. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 31 National Diet and Nutrition Survey20 The National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) was established in 1992 by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) and the Department of Health (DH). It is currently jointly funded and managed by the Food Standards Agency (FSA), with a contribution from the DH. The NDNS was originally set up as a series of cross-sectional surveys of diet and nutritional status of the population. The surveys have been split into four age groups: pre-school children in 1992 to 1993; older adults in 1994 to 1995; school-age children in 1997; and adults 2000 to 2001. One survey was carried out every two to three years. Data on consumption by individuals was gathered using a weighed intake dietary record for four to seven days. In April 2008, the NDNS changed to a rolling programme with data collected annually from approximately 500 adults and 500 children (older than 18 months old). The survey sample is designed to be representative of the UK population. Sample boosts have been carried out in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. There is scope for boosts in other population groups or add-on studies. The NDNS 2000/01 asked a series of questions relating to attitudes towards eating and exercise, specifically exploring the motivation to eat healthy or unhealthy foods and the extent to which this is emotionally motivated – these were not included in subsequent surveys. For this reason 2000/01 data is considered within this report. Data from the NDNS 2000/01 has been accessed from the UK data archive at individual level. Information presented in this paper is based on crude rates with no weightings applied. Target Group Index data21 Target Group Index (TGI) surveys collect information from samples of the population on a variety of aspects of life, including product and brand use, leisure activities, use of services, media exposure, preferences, attitudes and motivations. TGI data is collected in a continuous rolling fieldwork programme and is released quarterly (12 months data), with a sample size of around 20,000 people in England. The East Midlands Public Health Observatory has access to the DH’s Healthy Foundations dataset, which includes TGI data from October 2008 to September 2009. These data are used to create modelled profiles of groups of the population with particular characteristics. The data presented in this report is taken from the TGI data used for this segmentation. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 32 Appendix 3: data tablesd Adults Table 1: Appraisal of one’s own diet Overall what I usually eat is… N= All % Under weight % Healthy weight % Over weight % Obese % Morbidly obese % Very healthy 1179 18.5 12.7 20.5 19.0 13.6 9.6 Quite healthy 4579 72.0 68.4 70.6 73.3 73.9 78.8 Not very healthy 564 8.9 19 8.5 7.3 11.5 11.5 Very unhealthy 35 0.6 0.0 0.4 0.5 1.0 0.0 Source: HSE 2007 Table 2: Attitudes to healthy eating: proportions answering positively to statements (precise question not provided in data source) All % Under weight % Healthy weight % Over weight % Obese % Morbidly obese % Not stated % Total Sample (N=) 4928 126 2016 1464 829 108 385 I always think of the calories in what I eat 25.4 19.8 27.5 25.4 22.1 21.3 23.9 I think health foods are only bought by fanatics 14.4 12.7 12.7 15.9 16.2 20.3 12.2 I think fast food is all junk 35.0 35.7 35.9 35.9 34.0 33.3 29.6 I should do a lot more about my health 50.1 54.0 49.4 46.5 55.2 ↑ 53.7 54.3 I consider my diet to be very healthy 45.9 34.1 ↓ 46.9 47.8 42.8 36.1 46.2 I am eating more healthy food than I have in the past 60.2 50.8 61.0 61.8 58.6 58.3 57.7 I wouldn't let my children eat junk food 26.1 17.5 27.9 24.9 24.0 25.9 28.8 I get a lot of pleasure out of food 59.6 54.8 59.6 61.7 57.1 66.7 56.4 I like to treat myself to foods that are not good for me 47.3 54.0 48.7 45.9 45.5 52.8 45.5 Source: TGI 2008/09 Note: A ↑ symbol indicates a value that is significantly higher than that from the total sample and a ↓ symbol one that is significantly lower. d Percentages may not add up to 100% because numbers have been rounded to one decimal place. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 33 Table 3: Assessment of possible improvement to diet How easy or difficult would it be to make improvements to the way you eat? N= All Under Weight % Healthy Weight % Over Weight % Obese % Morbidly Obese % 79 2029 2093 1300 105 N= 6344 Very easy 702 8.9% 16.5 12.1 11.2 10.2 10.5 Quite easy 2869 37.1 41.8 47.8 45.4 45.8 43.8 Quite difficult 1192 19.5 20.3 15.5 17.5 25.1 23.8 Very difficult 149 2.7 1.3 1.8 2.3 2.9 5.7 No changes necessary 1432 31.7 20.3 22.8 23.6 16.1 16.2 Source: HSE 2007 Table 4: Barriers to a healthy lifestyle: proportions answering positively to statements (precise question not provided in data source) All % Under weight % Healthy weight % Over weight % Obese % Morbidly obese % Not stated % Total sample (N=) 4928 126 2016 1464 829 108 385 Time 33.0 31.8 37.5 ↑ 32.2 28.1 ↓ 15.7 ↓ 27.5 I already live a healthy lifestyle 31.2 36.5 37.3 ↑ 28.5 23.2 ↓ 16.7 ↓ 28.6 Other health problems I have 29.5 23.0 20.0 ↓ 30.7 44.9 ↑ 62.0 ↑ 34.0 Cost 22.4 26.2 22.1 22.8 20.6 33.3 ↑ 21.6 Lack of will power 17.3 10.3 15.5 17.2 23.9 ↑ 25.9 ↑ 12.2 ↓ Can't be bothered 8.1 6.4 7.6 8.2 11.5 ↑ 0.9 ↓ 5.7 Other responsibilities/ caring/child care 6.5 3.2 5.5 6.4 6.4 11.1 11.9 ↑ Access to facilities/ healthier choices 3.8 3.2 3.5 3.3 3.6 8.3 ↑ 6.0 Family influence/what family will do 2.8 2.4 3.1 2.1 2.6 2.8 4.2 Eating habits/eating the wrong foods 2.1 2.4 1.9 1.8 3.4 1.9 0.8 Source: TGI 2008/09 Note: A ↓ symbol indicates that the proportion of individuals within that BMI category who answered positively was significantly lower than the total sample and a ↑ symbol that it was significantly higher. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 34 Table 5: Understanding of recommendations for physical activity levels Which of the following statements applies to you? Respondents No. % I know what the recommended level of physical activity is 1320 27.5 I have heard of the recommended level of physical activity but don't know what it is 1966 40.9 I have not heard about the recommended level of physical activity 1523 31.7 Source: HSE 2007 Table 6: Use of physical activity facilities Used in the last 6 months (%) Used in the last year (%) Sport and leisure facilities 47.5 58.0 Parks and open spaces 80.9 88.4 Source: Place Survey Table 7: Appraisal of one’s own physical activity participation Underweight (%) Healthy Weight (%) Overweight (%) Total M F Total M M Very physically 17.5 10.9 active 13.8 25.0 9.5 15.2 25.3 14.9 19.0 Fairly physically 57.2 56.5 active 56.8 58.3 66.7 63.6 56.8 62.8 Not very physically 20.7 26.9 active 24.2 16.7 21.4 19.7 Not at all physically active 5.2 0.0 1.5 All (%) M 4.6 F 5.6 2.4 F F Morbidly Obese (%) Total M F Total M F Total 18.8 11.1 15.1 7.3 4.8 6.0 3.4 3.4 3.4 60.5 60.4 58.8 59.6 54.3 47.9 50.9 20.7 35.6 30.7 15.2 18.9 17.4 17.4 24.5 20.7 32.5 39.4 36.2 48.3 52.5 51.1 2.8 3.1 3.5 4.5 5.9 7.0 27.6 14.8 3.4 Total Obese (%) 5.6 7.9 8.5 Source: HSE 2007 NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 35 Children Table 8: Estimation of own weight (8–15 year olds) Given your age and height would you say that you are... Normal weight (%) Overweight (%) Obese (%) About the right weight 79.9 77.3 46.3 Too heavy 5.1 21.1 53.5 Too light 15.0 1.6 0.2 Source: HSE 2007 Table 9: Current dieting status (8–15 year olds) At the present time are you trying to lose weight, trying to gain weight or not trying to change your weight? Normal weight (%) Overweight (%) Obese (%) Trying to lose weight 11.7 37.6 65.1 Trying to gain weight 9.8 1.9 0.6 Not trying to change weight 78.5 60.5 34.3 Source: HSE 2007 Table 10: Physical activity levels compared with other people of same age by gender (11–15 year olds) Compared to other people of your own age would you describe yourself as..... Males (%) Females (%) All (%) Very physically active 42.4 29.3 35.8 Fairly physically active 47.6 55.3 51.2 Not very physically active 9.0 14.2 11.5 Not at all physically active 1.1 1.2 1.2 Source: HSE 2007 NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 36 References 1. Nutbeam D and Harris E. Theory in a Nutshell: A Practical Guide to Health Promotion. Sydney: McGraw-Hill, 2004. 2. MacDowell W, Bonnell C and Davies M. Health Promotion Practice. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill, 2006. 3. Bandura A. Self-efficacy in Changing Societies. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995. 4. Allender S, Cowburn G, Foster C. Understanding Participation in Sport and Physical Activity Among Children and Adults: A Review of Qualitative Studies, Health Education Research, 2006, 21(6), 826-835. 5. Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, Henderson KA, Kraft KM, Kerr J. An Ecological Approach to Creating Active Living Communities, Annual Review of Public Health, 2006, 27, 297-322. 6. Brug J. Determinantes of Healthy Eating: Motivation, Abilities and Environmental Opportunities, Family Practice, 2008, 25 (Supplement 1) i50-i55. 7. Shaw KA, O’Rourke P, Del Mar C, Kenardy J. Psychological Interventions for Overweight or Obesity, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2005, Issue 2. 8. Roberts K. Data Sources: Knowledge of an Attitudes to Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Oxford: National Obesity Observatory, 2010 9. The Information Centre, Health Survey for England 2007: Summary of key findings. Leeds: The Information Centre, 2008. 10. Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, Henderson, KA, Kraft, KM, Kerr, J. An Ecological Approach to Creating Active Living Communities, Annual Review of Public Health, 2006, 27, 297-322 11. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Behaviour Change at Population, Community and Individual Levels. London: Department of Health, 2007. 12. National Centre for Social Research and University College London. Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Health Survey for England, 2007 [computer file]. 2nd Edition. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], April 2010. SN: 6112. 13. Sport England, Active People Survey, 2007-2008 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], December 2009. SN: 6347. 14. Communities and Local Government and Audit Commission, Place Survey, 2008 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], September 2010. SN: 6519. 15. Ofsted Tell Us 3 National Report. London: Department for Education and Skills, 2008. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 37 16. Food Standards Agency Consumer Attitudes to Food Standards: Wave 8, UK Final Report. London: Food Standards Agency, 2007. 17. National Centre for Social Research et al., Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey, 2003-2005 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], March 2008. SN: 5808. 18. National Centre for Social Research, British Social Attitudes Survey, 2008 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], March 2010. SN: 6390. 19. Sodexho Ltd The Sodexho School Meals and Lifestyle Survey 2005. Swindon: Sodexho Ltd, 2005. 20. Office for National Statistics. Social and Vital Statistics Division and Food Standards Agency, National Diet and Nutrition Survey : Adults Aged 19 to 64 Years, 2000-2001 [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], May 2005. SN: 5140. 21. Department of Health Healthy Foundations: A Segmentation Model. London: Department of Health, 2010. NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 38 Reader Information Title Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us. Author(s) Kath Roberts Katie Marvin Reviewer(s) Ken Fox, University of Bristol Jane Appleton, Oxford Brookes University Jilly Martin, Oxford Brookes University Publication date May 2011 Target audience Public health and other professionals working in local authorities and other public health organisations who are interested in attitudes to and knowledge of healthy eating and physical activity in the population. Description This paper draws on the data sources identified in the paper; ‘Data sources: knowledge of and attitudes to healthy eating and physical activity’, presents analysis of the data and provides some background to its relevance to healthy eating and physical activity behaviours. How to cite Roberts, K and Marvin, K. Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us. Oxford: National Obesity Observatory, 2011. Contact National Obesity Observatory www.noo.org.uk info@noo.org.uk Electronic location http://www.noo.org.uk/NOO_pub/briefing_papers Copyright © National Obesity Observatory National Obesity Observatory NOO | Knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating and physical activity: what the data tell us 39