chapter five - tecs online

advertisement

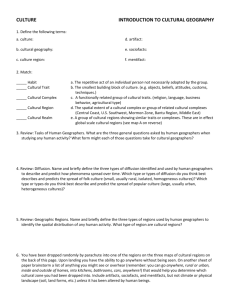

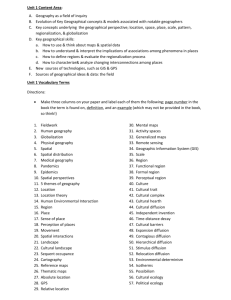

I N T R O D U C T I O N T O C U L T U R A L G E O G R A P H Y LESSON OBJECTIVES 1. Explain how culture regions are made, remade, and used by humans. 2. Cite examples of how culture diffuses from one place to another. 3. Explain how humans manage their natural resources in relation to selected theories on cultural ecology. 4. Explain how varied cultures are integrated in relation to economic and cultural determinism. 5. Discuss the effects of human activities on cultural landscapes. Chapter 5 Darfur Conflict: ACase in point The Darfur Conflict in Sudan, which begun in 2003 is presented as an example of the how the humanenvironment relationship may be seen from a geographical perspective. While the said conflict has varied root causes, the article presents the impact of geographical forces on the ongoing strife. he conflict and resulting human tragedy that have unfolded in Darfur since 2003 have grabbed international headlines. As the UN Security Council hammered out a deal to get an international peacekeeping force deployed there, discussions about how to understand the causes of the conflict intensified. When Darfur first made headlines, the most common way of explaining the context was in terms of ethnic differences between Arabs and Africans. More recently, some have argued – UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon among them – that ‘the Darfur conflict began as an ecological crisis, arising at least in part from climate change. No conflict ever has a single cause. In the case of Sudan, the escalation of violence has been attributed to such factors as: historical grievances; local perceptions of race; demands for a fair distribution of power between different groups; the unfair distribution of economic resources and benefits; disputes over access to and control of increasingly scarce land, livestock and water between pastoralists and agriculturalists; small arms proliferation and the militarization of youth; and weak state institutions. Arab-African differences are not as clear cut as some commentators first thought. Political and military alliances frequently shift between ethnic groups, depending on pragmatic considerations. The difference between herders and farmers is also variable. According to the UN Environment Programme, the rural livelihood structures in Sudan are complex and vary from area to area. In many cases, farmers and herders are not separable as some tribes practice both herding and crop cultivation. The impact of climate change, in particular the 20-year Sahelian drought, played a major role in intensifying grievances in Sudan because it meant there was less land for both farming and herding. These issues played out against a background of economic and political marginalization, as well as violence. The number of violent conflicts attributable to traditional disputes over the use of land escalated dramatically from the 1970s on. In the mid-1980s, when the north-south Sudanese civil war broke out again after a 10-year hiatus, the government used Arab tribal militias as a means of keeping the southern rebels at bay in Darfur. As a result, ethnic identity started to become more politicized, feeding the escalation T 49 49 I N T R O D U C T I O N T O C U L T U R A L G E O G R A P H Y of conflicts over land issues with much more destructive fighting than in former times. In 2003 two Darfurian armed groups attacked military installations; the response of local government backed militias was a further escalation with a campaign of ethnic cleansing, causing over 200,000 deaths and the displacement of over two million. Thus climate change alone does not explain either the outbreak or the extent of the violence in Darfur. The other 16 countries in the Sahelian belt have felt the impact of global warming, including Mali and Chad, but only Sudan has experienced such devastating conflict. Darfur is, in fact, an exemplary case showing how the physical consequences of climate change interact with other factors to trigger violent conflict. The conflict itself is taking a further toll of already scarce resources. Militias in Darfur are known for the intentional destruction of villages and forests. The loss of trees in these campaigns reduces the amount of shelter available for livestock and the amount of fuel wood for local communities. This threatens their livelihoods and results in their displacement, while simultaneously worsening the impact of desertification, which makes further conflict over land access more likely. The massive scale of displacement in Darfur also has a serious impact on the environment. Camps for displaced people mean trees being felled for firewood. The consumption is greater in the many camps where manufacturing bricks is being taken up as a means for people to earn a living, encouraged by development organizations such as DFID. These camps can require up to 200 trees per day for brick-making. Over the weeks and months, combined with the wood needed for domestic use, this adds up to a rate of deforestation that renders the camps unsustainable. Deforestation already extends as far as 18 kilometers from some camps, as people go further and further afield to find wood. Most of those who go to gather wood in this way are women and children, and this task makes them extremely vulnerable to continuing violence from the militia groups. The incidence of rape has risen as an inevitable result. As the wood runs out, the camps eventually have to move. This is not only hugely disruptive to the hundreds of thousands of camp inhabitants, but it is also detrimental to Darfur’s existing problems of drought, desertification and disputes over land-use, which were contributory factors to the conflict from the outset. Cultural Geography (Jordan and Rowntree, 1990 with modifications) Cultural Geography is the study of spatial variations among cultural groups and the spatial functioning of society. It focuses on describing and analyzing the ways language, religion, economy, government, and other cultural phenomena vary or remain constant from one place to another and on explaining how humans function spatially. Cultural geography is, at heart, a celebration of human diversity. 50 I N T R O D U C T I O N T O C U L T U R A L G E O G R A P H Y Geographers seek to learn how and why cultures differ or are similar, from one place to another. Often those similarities have visual expression. In what ways are these two structures—one a Methodist Church and the other a Seventh Day Adventist Tabernacle—alike and different? The Methodist Church Jireh Tabernacle Seventh Day Adventist Source: http://www.anguilla-beaches.com/anguillaphotos-churches.html Themes in Cultural Geography 1. Culture Region. Region is the word and concept used by geographers to mean a grouping of like places or the functional union of places to form a spatial unit. Formal Culture Region—defined as uniform area inhabited by people who have one or more cultural traits in common. Geographers find the culture region useful for grouping people with similar cultural traits. It is a tool geographers can use to describe spatial differences in culture. For example, a Waray-language culture region can be drawn on a map of Philippine languages, and it would include the area where Waray is spoken. This example represents the concept of formal region in its simplest level. It is based on a single cultural trait. Commonly, culture regions depend on multiple related traits. 51 I N T R O D U C T I O N T O C U L T U R A L G E O G R A P H Y In this market in rural Vietnam, various facets of multi trait formal region are apparent. Agricultural products, marketing and clothing all contribute to the region’s identity. Source: http://www.ifad.org/photo/images/10196_O34s.jpg It should be noted that the formal culture region is the geographer’s somewhat arbitrary creations. No two cultural traits have the same distribution and the territorial extent of a culture region depends on what defining traits are used. For example, Ilokanos and Tagalogs differ in language. On the basis of language, these two would form separate culture regions. However, Ilokanos and Tagalogs share many other cultural traits in common, partly because of similar historical experience (say, both were colonized by the Spaniards for a span of 300 years). Both generally have a common taste of fashion, pop songs, and religion. Functional Culture Region—The hallmark of formal type is cultural homogeneity, and formal region is abstract rather than concrete. By contrast, the functional culture region is generally not culturally homogenous. Instead, it is an area that has been organized to function politically, socially, or economically. A city, an independent state, a church diocese or parish, a trade area are all examples of functional regions. Functional regions have nodes, or central points where the functions are coordinated and directed. Examples of such nodes are city halls, national capitals, precinct voting places, parish churches, factories, farmsteads, and banks. In this sense, functional regions also possess a core/periphery configuration, in common with formal groups. Some functional culture regions have definite boundaries but it is best to imagine these borders in terms of increasing or diminishing flows of energy out of or into nodes. On a map, this motion might be represented by directional arrows rather than boundary lines—as a network, not a territory. A good example is daily newspaper’s trade. The node for the paper would be a plant where it is produced. Every morning, trucks move out of the plant to distribute the paper throughout the city. The newspaper may have sales outside the city towards rural areas and nearby towns. There, its sales area overlaps the territories of competing newspapers published in other cities. It would be futile to try to define borders for such a process. How would you draw a sales area boundary for The Philippine Daily Inquirer? 52 I N T R O D U C T I O N T O C U L T U R A L G E O G R A P H Y Vernacular or Perceptual Region—perceived to exist by its inhabitants, as evidenced by the widespread acceptance and use of a regional name. Some vernacular regions are based on physical environmental features, while others find their basis in economic, political, historical, or promotional aspects. Vernacular regions like most culture regions, generally lack sharp borders, and the inhabitants of any given area may claim residence in more than one such region. These regions are often created by publicity campaigns, and their use in the communications media has a lot to do with acceptance by the local population. 2. Cultural Diffusion. This is the spatial spread of learned ideas, innovations, and attitudes. Any culture is the product of almost countless innovations that spread from their points of origin to cover a wider area. Some of these innovations occurred thousand of years ago, others very recently. Some spread widely while others remained confined to their area of origin. Expansion Diffusion—Ideas spread throughout a population, from area to area, in a snowballing process, so that the total number of knowers and the area of occurrence become ever greater. Relocation Diffusion—Occurs when individuals or groups with a particular idea move bodily from one location to another, thereby spreading the innovation to their new homeland. Each symbol is one person or place Original Knower Knower Contagious expansion diffusion Very important Person Non-Knower Path of diffusion Prospective place of migration Hierarchical expansion diffusion Before migration After migration Relocation diffusion 53 Types of cultural diffusion are presented here. These diagrams are merely suggestive; in reality, spatial distribution is far more complex. In hierarchical diffusion, different scales can be used, so that, for example, a “very important person” could be replaced by “large city”. I N T R O D U C T I O N T O C U L T U R A L G E O G R A P H Y Expansion diffusion can be further divided into subtypes called hierarchical and contagious diffusion. In hierarchical diffusion, ideas leapfrog from one important person to another or from one urban center to another, temporarily bypassing other persons or rural territory. By contrast, contagious diffusion involves the general spread of ideas, without regard to hierarchies, in a manner of a contagious disease. Sometimes a specific trait is rejected, but the underlying idea is accepted. This is known as stimulus diffusion. 3. Cultural Ecology. Cultural geographers look on people and nature as interacting. Each human group and the way of life it has developed occupy a piece of the physical earth. Cultures interact wit the environment, and is necessary for the cultural geographer to study this interaction in order to understand spatial variations in culture. This study is called cultural ecology. “Ecology” here is used to refer to the two-way relationship between an organism and its physical environment. A “physical environment” is understood to include climate, terrain, soil, natural vegetation, wildlife, and other aspects of the physical surroundings. Another frequently used word is “ecosystem”. By this, we seek to describe the functioning ecological system in which biological and cultural Homo sapiens live and interact with the physical environment. In sum, we define cultural ecology as the study of (1) environmental influence on culture, and (2) the impact of people, acting through their culture, on the ecosystem. “Phasing out the human race will solve every problem on earth, social and environmental.”—Dave Forman, Founder of Earth First! “If I were reincarnated, I would wish to be returned to Earth as a killer virus to lower human population levels”. — Prince Phillip, World Wildlife Fund [Source: Cartoon and quotes from, Alan Caruba, http://www.canadafreepress.com/ index.php/article/28875 Through the years, cultural geographers developed various perspectives on the spatial interaction between humans and the land. In a broad sense, schools of thoughts have developed: Environmental determinism—Physical environment, especially the climate and terrain, is the active force in shaping cultures—that humankind was essentially a passive product of the physical surroundings. Hence, environmental determinists view cultural ecology as a “oneway street”. Determinists believe that peoples of the mountains were predestined by the rugged terrain to be simple, backward, conservative, unimaginative, and freedom loving. Temperate climates produced inventiveness, industriousness, and democracy, whereas coastlands produced great navigators and fishermen. 54 I N T R O D U C T I O N T O C U L T U R A L G E O G R A P H Y Possibilism—Since the 1930’s, environmental determinism has fallen from favor among cultural geographers. Possibilism has taken its place. Possibilists do not ignore the influence of the physical environment, and they realize that the imprint of nature shows in many cultures. However, possibilists stress that cultural heritage is at least as important as the physical environment in affecting human behavior. Possibilists argue that people are the primary architects of their culture, not the environment. For them, any physical environment offers a number of possible ways for a culture to develop. How people use and inhabit an area depends on the choices they make among the possibilities offered by the environment. Most possibilists feel that the higher the technological level of a culture, the greater the number of possibilities and the weaker the influences of the environment. Environmental perception—Each person and cultural group has its own mental images of the physical environment. To describe such mental images, cultural geographers use the term environmental perception. Environmental perceptionists declare that the choices people make will depend more on what they perceive the environment to be than on the actual character of the land. The perceptionist maintains that people cannot perceive their environment with exact accuracy and that decisions are therefore based on distortions of reality. To understand why a cultural group developed as it did in its physical environment, geographers must know not only what the environment is like, but also what the members of the culture think it is like. An excellent example is geomancy, as East Asian world view and art. Geomancy, called fengshui in Chinese, is a traditional system of land-use planning dictating that certain environment settings deemed by the sages to be particularly auspicious should be chosen as the sites for houses, villages, temples, and graves. 4. Cultural Integration. The explanation of human spatial variations requires consideration of a whole range of cultural factors. The cultural geographer recognizes that all facets of culture are systematically and spatially intertwined, or integrated. In short, cultures are complex wholes rather than series of unrelated traits. They are integrated units in which the parts fit together causally. The themes of cultural integration reflect the geographer’s awareness that the immediate causes of some cultural phenomena are other cultural phenomena. To get at the ways culture is integrated, at how space is organized by humans, geographers generally seek to strip down reality, separating different causal factors. They are aware that in the real world, so many causes are involved in any problem that confusion may result, and so they have employed a simpler way of testing how a culture works. It is called model building. A good example of this is the Von Thunen model (see chapter on Geographer’s Tools). The purpose of Thunen’s model was to study the effect of transportation costs and increased distance from the market on agricultural land use. Theorists and model builders tend to regard geography as nomothetic, or law-giving science, believing that the chief purpose of geographical scholarship should be discovery of universal principles. They feel that cultural geography belongs to the social sciences, 55 I N T R O D U C T I O N T O C U L T U R A L G E O G R A P H Y alongside economics. Those who claim such idea are accused of economic determinism—the belief that human behavior is largely dictated by economic motivation. The theme of cultural integration can also lead the geographer to cultural determinism—which maintains that the physical environment is inconsequential as an influence on culture. Any facet of a culture, cultural determinists argue, is shaped entirely by other facets of culture. Cultural integration for them offers all the answers for spatial variations. People and culture are the active forces; nature is passive and easily conquered. What are the pros and cons of a society with a muti-ethnic composition? Is cultural integration possible amidst cultural diversity? How could we ease tensions brought about by “culture clashes”? [Source: Cool Shaker.net, 2008, http://www.coolershaker.net/wpcontent/uploads/2008/06/school.jpg 5. Cultural Landscape. This is the artificial landscape that cultural groups create in inhabiting the Earth. Cultures have shaped their own landscapes out of the raw materials provided by the Earth. Every inhabited area has a cultural landscape, fashioned from the natural landscape, and each uniquely reflects the culture that created it. Rice cultivation on the slopes of the mountains of Ifugao, in the island of Luzon, Philippines, is the basis of a highly distinctive cultural landscape. Source: www.flickr.com 56 I N T R O D U C T I O N T O C U L T U R A L G E O G R A P H Y Landscape mirrors culture, and the cultural geographer can learn much about a group of people by carefully observing the landscape. Some cultural geographers regard landscape study as the core of geographical concern, geography’s central interest. For them, landscape reflects the most basic strivings of humankind: for shelter, food, clothing, and entertainment. The cultural landscape also reflects different attitudes concerning modification of the earth’s surface. In addition, the landscape contains valuable evidence about the origin, spread, and development of cultures, since it usually preserves relic forms of various types. A relic form embedded in the modern urban landscape of Baguio City, Philippines, this 1936 American-Period Catholic Church is a valuable index of a colonial culture. [Source:http://upload.wikimedia.org /wikipedia/commons/e/ee/Baguiocat h1.JPG] The content of the cultural landscape is both varied and complex. Most geographical studies have focused on three principal aspects of this landscape: settlement patterns, landdivision patterns, and architecture. In the study of settlement patterns, cultural geographers describe and explain the spatial arrangement of buildings, roads, and other features that people construct while inhabiting an area. Land-division patterns reveal the way people have divided the land for economic and social uses. For architecture, we can distinguish two types in the cultural landscape: folk architecture and professional architecture. 57