Fun stage…the preschool years!

advertisement

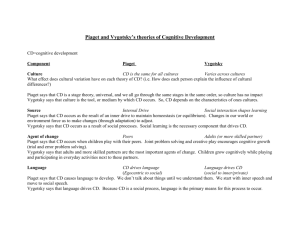

Fun stage…the preschool years! Height and Weight The average child grows 2½ inches and gains between 5 and 7 pounds a year in early childhood. The percentage of increase in height and weight decreases with each additional year. Body fat shows a steady decline during this time. Girls are only slightly smaller and lighter than boys, but they have more body fat while boys have more muscle tissue. Boys and girls slim down as their trunks lengthen. Individual Differences. Much of the variation in body size is due to heredity. The two most important contributors to height differences are ethnic origin and nutrition. Contributors to Short Stature: • Congenital Factors (genetic or prenatal problems). Preschool children whose mothers smoked regularly during pregnancy are shorter than their counterparts whose mothers did not smoke. • Physical Problems That Develop in Childhood. Children who are chronically sick are shorter than their counterparts who are rarely sick. • Emotional Difficulties. Children who have been physically abused or neglected may not secrete adequate growth hormone, which can restrict their physical growth. The Brain The brain and the head grow more rapidly than any other part of the body. By age 3, the brain is three-quarters of its adult size, and by age 5, the brain has reached about nine-tenths of its adult size. Some of this size increase is due to increase in size and number of nerve endings and an increase in myelination. Myelination is believed to be important in the maturation of a number of children’s abilities. From 3-6 years of age, researchers have found that the most rapid brain growth occurs in the frontal lobe. ‹#› Gross Motor Skills • At 3 years of age, children enjoy simple movements, such as hopping, jumping, and running, just for the fun of it and the pride they feel in their accomplishment. • At 4 years of age, children become more adventurous—taking on jungle gyms and climbing stairs with one foot on each step. • At 5 years of age, children begin to perform hair-raising stunts on anything they can climb on, and they enjoy racing with each other and with parents. Fine Motor Skills • At age 3, children are still clumsy at picking up very small objects between their thumb and forefinger. Three-year-olds can build very high block towers, but the blocks are usually not in a perfectly straight line. Puzzles are approached with a good deal of roughness and imprecision. • By age 4, their coordination has improved and become more precise. • By age 5, children are no longer interested in building towers, but rather houses, churches, and buildings with more detail. Handedness Preference for one hand is linked with the dominance of one brain hemisphere with regard to motor performance. Right-handers have a dominant left hemisphere, while left-handers have a dominant right hemisphere. Evidence of handedness is present in infancy, as babies show preferences for one side of their body over the other. Many preschool children use both hands without a clear preference emerging until later in childhood. The origin of hand preference has been explored with regard to genetic inheritance and environmental experience. ‹#› Energy Needs What children eat affects their skeletal growth, body shape, and susceptibility to disease. An average preschool child requires 1,700 calories per day. Energy requirements for children are determined by the basal metabolism rate (BMR): the minimum amount of energy a person uses in a resting state. Differences in physical activity, basal metabolism, and the efficiency with which children use energy are among the possible explanation as to why children of the same age, sex, and size vary in their energy needs. Eating Behavior Eating habits become ingrained very early in life. It is during the preschool years that many children get their first taste of fast food. Our changing lifestyles, in which we often eat on the run and pick up fast food meals, contribute to the increased fat levels in children’s diets. Although such meals are high in protein, the average American child does not need to be concerned about getting enough protein. Obesity in Childhood Being overweight can be a serious problem in childhood. Overweight preschool children are usually not encouraged to lose a great deal of weight, but to slow their rate of weight gain so they will grow into a more normal weight for their height. Prevention of obesity in children includes helping children and parents see food as a way to satisfy hunger and nutritional needs, not as proof of love or a reward. Routine physical activity should be a daily event. The United States Accidents are the leading cause of death in young children: motor vehicle accidents, drowning, falls, and poisoning are high on the list. The disorders most likely to be fatal during early childhood today are birth defects, cancer, and heart disease. Despite the greatly diminished dangers of many childhood diseases, it is still very important for parents to keep young children on an immunization schedule. Exposure to tobacco smoke increases children’s risk for developing a number of medical problems, such as pneumonia, bronchitis, ear infections, burns, asthma, and cancer in adulthood. The State of Illness and Health of the World’s Children One death of every three in the world is the death of a child under 5 years of age. Every week, more than a quarter million children die in developing countries due to infection and undernutrition. The leading cause of childhood death in the world is dehydration and malnutrition as a result of diarrhea. This could be prevented if parents had available a low-cost breakthrough known as oral rehydration therapy (ORT). Oral rehydration therapy involves a range of techniques designed to prevent dehydration during episodes of diarrhea by giving the child fluids by mouth. Characteristics of the Preoperational Stage The preoperational stage lasts from 2-7 years old. During this time stable concepts form, mental reasoning emerges, egocentrism begins, and magical beliefs are constructed. Thought is flawed and not organized. This stage involves a transition from primitive to more sophisticated use of symbols. Children still do not yet think in an operational way. Definition of Operations Operations are internalized sets of actions that allow the child to do mentally what before she did physically. Symbolic Function Substage The ability to think symbolically and to represent the world mentally predominates in this substage. It occurs roughly between the ages of 2-4. Symbolic function is demonstrated by the child’s ability to mentally represent an object not present. Symbolism is evident in scribbled designs, language, and pretend play. Two important limitations in thought at this stage are egocentrism and animism. • Egocentrism Egocentrism is the inability to distinguish between one’s own perspective and someone else’s perspective. It is a salient feature of preoperational thought. Perspective-taking doesn’t develop uniformly in preschool children, as they frequently show perspective skills on some tasks, but not others. • Animism Animism is the belief that inanimate objects have “lifelike” qualities and are capable of action. A child may believe that a tree pushes its leaves off in the Fall, or that the sidewalk made him trip and fall down. Intuitive Thought Substage In this stage, children begin to use primitive reasoning and want to know the answers to all sorts of questions. It occurs roughly between the ages of 4-7. Piaget used the term intuitive because children say they know something, but they know it without the use of rational thinking. Children in this stage also ask a barrage of questions, signaling the emergence of their interest in reasoning and why things are the way they are. • Centration Centration is the focusing or centering of attention on one characteristic to the exclusion of all others. It is a major characteristic of preoperational thought, evidenced in young children’s lack of conservation. • Conservation Conservation refers to an awareness that altering an object’s or a substance’s appearance does not change its basic properties. Although obvious to adults, preoperational children lack conservation. A lack of conservation not only demonstrates the presence of centration, but also an inability to mentally reverse actions. ‹#› Here are a few examples. The Zone of Proximal Development The zone of proximal development is Vygotsky’s term for the range of tasks too difficult for children to master alone, but which can be learned with the guidance and assistance of adults or more skilled children. The lower limit is the level of problem solving reached by the child working independently. The upper limit is the level of additional responsibility the child can accept with the assistance of an able instructor. Vygotsky’s emphasis on the ZPD underscores his belief in the importance of social influences, especially instruction, on children’s cognitive development. Scaffolding in Cognitive Development Scaffolding refers to changing the level of support. Over the course of a teaching session, a more skilled person adjusts the amount of guidance to fit the student’s current performance level. Dialog is an important tool of scaffolding in the zone of proximal development. As the child’s unsystematic, disorganized, spontaneous concepts meet with the skilled helper’s more systematic, logical, and rational concepts, through meeting and dialogue, the child’s concepts become more systematic, logical, and rational. Language and Thought Vygotsky believed that young children use language both for social communication and to plan, guide, and monitor their behavior in a selfregulatory fashion. Language used for this purpose is called inner speech or private speech. For Piaget, private speech is egocentric and immature, but for Vygotsky it is an important tool of thought during early childhood. Vygotsky believed all mental funtions have social origins. Children must use language to communicate with others before they can focus on their own thoughts. Researchers have found support for Vygotsky’s view of the positive role of private speech in development. Evaluating and Comparing Vygotsky’s and Piaget’s Theories Vygotsky’s theory is a social constructivist approach, which emphasizes the social contexts of learning and that knowledge is mutually built and constructed. Piaget’s theory does not have this social emphasis. For Piaget, children construct knowledge by transforming, organizing, and reorganizing previous knowledge. For Vygotsky, children construct knowledge through social interaction. The implication of Piaget’s theory for teaching is that children need support to explore their world and discover knowledge. The implication of Vygotsky’s theory for teaching is that students need many opportunities to learn with the teacher and more skilled peers. Vygotsky’s theory has been embraced by many teachers and successfully applied to education. Teaching Strategies Based on Vygotsky’s Theory •Use the child’s zone of proximal development in teaching. •Use scaffolding. •Use more skilled peers as teachers. •Monitor and encourage children’s use of private speech. •Assess the child’s ZPD, not IQ. •Transform the classroom with Vygotskian ideas. ‹#› A comparison of Piaget and Vygotsky. Attention The child’s ability to pay attention changes significantly during the preschool years. Preschool children are influenced strongly by the features of a task that stand out, or are salient. This deficit can hinder problem solving or performing well on tasks. By age 6 or 7, children attend more efficiently to the dimensions of a task that are relevant. This is believed to reflect a shift in cognitive control of attention. Memory Short-Term Memory In short-term memory, individuals retain information for up to 15-30 seconds, assuming there is no rehearsal, which can help keep information in STM for a much longer period. Differences in memory span occur across the ages due to: • Rehearsal: older children rehearse items more than younger children. • Speed and efficiency of processing information: the speed with which a child processes information is an important aspect of the child’s cognitive abilities. Long-Term Memory Young children can remember a great deal of information if they are given appropriate cues and prompts. Sometimes the memories of preschoolers seem to be erratic, but these inconsistencies may be to some degree the result of inadequate prompts and cues. Strategies Strategies consist of using deliberate mental activities to improve the processing of information, such as rehearsal and organizing information. Young children typically do not use rehearsal and organization. Children as young as 2 can learn to use other types of strategies to process information. The Young Children’s Theory of Mind Theory of mind refers to individuals’ thoughts about how mental processes work. Even young children are curious about the nature of the human mind. Children’s developing knowledge of the mind includes the awareness that: • The mind exists. By the age of 2 or 3, children refer to needs, emotions, and mental states. They also use intentional action or desire words, such as wants to. Cognitive terms such as know, remember, and think usually appear after perceptual and emotional terms, but are used by age 3. Later children distinguish between guessing vs. knowing, believing vs. fantasizing, and intending vs. not on purpose. • The mind has connections to the physical world. At about 2 or 3 years of age, children develop an awareness of the connections among stimuli, mental states, and behavior. This provides them with a rudimentary mental theory of human action. Children can infer connections from stimuli to mental states, from mental states to behavior or emotion, and from behavior to mental states. Children also develop an understanding that the mind is separate from the physical world. • The mind can represent objects and events accurately or inaccurately. Children develop an understanding that the mind can represent objects and events accurately. Understanding of false beliefs doesn’t usually occur until 4 or 5 years. • The mind actively interprets reality and emotions. Children develop an understanding that the mind actively mediates the interpretation of reality and the emotion experienced. In the elementary school years, children change from viewing emotions as caused by external events without any mediation by internal states to viewing emotional reactions to an external event as influenced by a prior emotional state, experience, or expectation. ‹#› Young children’s understanding sometimes gets ahead of their speech. Many of the oddities of young children’s language sound like mistakes to adult listeners, but from the children’s perspective, they are not. As children go through early childhood, their grasp of the rules of language increases (morphology, semantics, pragmatics). Morphology As children move beyond two-word utterances, they know morphology rules. They begin using plurals and possessive forms of nouns. They put appropriate endings on verbs. They use prepositions, articles, and various forms of the verb to be. Children demonstrate knowledge of morphological rules with plural forms of nouns, possessive forms of nouns, and the third-person singular and past tense forms of verbs. Semantics As children move beyond the two-word stage, their knowledge of meanings rapidly advances. The speaking vocabulary of a 6-year-old ranges from 8,000 to 14,000 words. According to some estimates, the average child of this age is learning about 22 words a day! Pragmatics No difference is as dramatic as the difference between a 2-year-old’s language and a 6-year-old’s language in terms of pragmatics—the rules of conversation. At about 3 years of age, children improve their ability to talk about things that are not physically present—referred to as “displacement.” Displacement is revealed in games of pretend. Large individual differences seen in preschoolers’ talk about imaginary people and things. ‹#› Children in academically oriented, direct-instruction approaches did better on achievement tests and were more persistent on tasks than were children in other approaches. Children in effective education programs were absent less often and showed more independence. Long-term effects have included lower rates of placement in special education, dropping out of school, grade retention, delinquency, and use of welfare programs. The Child-Centered Kindergarten In the child-centered kindergarten, education involves the whole child and includes concern for the child’s physical, cognitive, and social development. Instruction is organized around the child’s needs, interests, and learning styles. The process of learning, rather than what is learned, is emphasized. Experimenting, exploring, discovering, trying out, restructuring, speaking, and listening are all part of an excellent kindergarten program. The Montessori Approach The Montessori Approach is a philosophy of education in which children are given considerable freedom and spontaneity in choosing activities. They are allowed to move from one activity to another as they desire. The teacher acts as a facilitator, rather than a director of learning. While it fosters independence, it de-emphasizes verbal interaction. Criticism of the approach is that it neglects children’s social development and restricts imaginative play. Young Children Young children learn best through active, hands-on teaching methods. Schools should focus on improving children’s social as well as cognitive development. Developmentally appropriate practice is based on knowledge of the typical development of children within an age span, as well as the uniqueness of the child. Developmentally inappropriate practice ignores the concrete, hands-on approach to learning. Direct teaching largely through abstract paper-and-pencil activities presented to large groups of young children is believed to be developmentally inappropriate. Does Preschool Matter? Preschool matters if parents do not have the commitment, time, energy, and resources to provide young children with an environment that approximates a good early childhood program. If parents have the competence and resources to provide young children with a variety of learning experiences and exposure to other children and adults, along with opportunities for extensive play, this may be sufficient. Education for Children Who Are Disadvantaged Project Head Start is a compensatory education program designed to provide children from low-income families the opportunity to acquire skills and experiences important for success in school. Project Follow Through was implemented as an adjunct to Project Head Start to determine which types of educational programs were the most effective, and those were then carried through the first few years of elementary school. ‹#› Initiative Versus Guilt Children use their perceptual, motor, cognitive, and language skills to make things happen. The governor of initiative is conscience, as children begin to hear the inner voice of self-observation. Initiative may bring rewards or punishment. Widespread disappointment leads to an unleashing of guilt that lowers self-esteem. Leaving this stage with a sense of initiative rather than guilt depends on parental responses to children’s self-initiated activities. Self-Understanding The child’s cognitive representation of self, the substance and content of the child’s self-conceptions. Based on the various roles and membership categories that define who they are. In early childhood, children usually conceive of the self in physical terms. The active dimension is a central component of the self, as children describe themselves in terms of such activities as play. Emotional Development Among the most important changes in emotional development are the increased use of emotion language and the understanding of emotion. Between 2 and 3 years, children considerably increase the number of terms they use to describe emotion. Children also begin to learn about the causes and consequences of feelings. At 4-5 years, children show an increased ability to reflect on emotions. They also show a growing awareness about controlling and managing emotions to meet social standards. ‹#› What Is Moral Development? Involves thoughts, feelings, and behaviors regarding standards of right and wrong. Has an intrapersonal dimension and an interpersonal dimension. The former regulates a person’s activities when he or she is not engaged in social interaction. The latter regulates people’s social interactions and arbitrates conflict. Piaget’s View of Moral Development Heteronomous Morality The first stage of Piaget’s theory of moral development occurs from approximately 4-7 years of age. Justice and rules are conceived of as unchangeable properties of the world, removed from the control of people. This stage involves the belief in imminent justice—the concept that, if a rule is broken, punishment will be meted out immediately. Autonomous Morality Piaget’s second stage of moral development, which begins around age 10 and continues throughout life. At this point, the child realizes that rules and laws are created by people and that, in judging an action, one should consider the actor’s intentions as well as the consequences. Children between the ages of 7 and 10 are in transition and show features of both stages. Moral Behavior The study of moral behavior has been influenced by behavioral and cognitive theories. The processes of reinforcement, punishment, and imitation are used to explain moral behavior. The social cognitive view believes that moral behavior is influenced extensively by the situation. Social cognitive theorists also believe that the ability to resist temptation is closely tied to the development of self-control. They believe cognitive factors are important in the development of self-control. Moral Feelings The Psychoanalytic Approach The superego is the moral branch of personality. It develops as the child resolves the Oedipus conflict and identifies with the same-sex parent. Through identification with the same-sex parent, children internalize the parents’ standards of right and wrong that reflect societal prohibitions. Children conform to societal standards to avoid guilt, brought on by hostility originally directed at the same-sex parent, now internalized and directed toward the self. Empathy Reacting to another’s feelings with an emotional response that is similar to the other’s feelings. Empathy is experienced as an emotional state, but it also has a cognitive component. The cognitive component is the ability to discern another’s inner psychological states—perspective taking. Emotions such as empathy, shame, guilt, and anxiety provide a natural base for the child’s acquisition of moral values. ‹#› What Is Gender? Sex - the biological dimension of being male or female. Gender - the social dimensions of being male or female. Gender identity - the sense of being male or female. Gender role - a set of expectations that prescribe how males or females should think, act, and feel. Biological Influences The 23rd pair of chromosomes in humans either contains two X chromosomes to produce a female, or an X and a Y chromosome to produce a male. Estrogens influence the development of female physical sex characteristics. Androgens promote the development of male physical sex characteristics. Some research is exploring possible differences in aspects of male and female brains. Social Influences Psychoanalytic and Social Cognitive Theories Psychoanalytic theory maintains a preschool attraction to the opposite-sex parent ultimately results in identification with the same-sex parent. Social cognitive theory emphasizes gender development occurs through observation and imitation of gender behavior, and through the rewards and punishments for gender appropriate and inappropriate behavior. Critics of this approach argue that gender development is not as passive as it indicates. Parental Influences Both mothers and fathers are psychologically important in children’s gender development. By action and example, they influence their children’s gender development. Fathers are more likely to ensure that boys and girls conform to existing cultural norms. Fathers are more involved in socializing their sons than their daughters. Fathers are more likely than mothers to act differently toward sons and daughters, thus contributing more to distinctions between genders. Peer Influences Children show a clear preference for being with and liking same-sex peers. This tendency becomes stronger during the middle and late childhood years. Boys teach one another the required masculine behavior and enforce it strictly. Girls pass on female culture and congregate with one another. Peer demands for conformity to gender roles become especially intense during adolescence. School and Teacher Influences Girls’ learning problems are not identified as often as boys’ are. Boys are given the lion’s share of attention in schools. Girls start school testing higher in every academic subject, yet graduate scoring lower on the SAT. Boys are most often at the top of their classes, but most often at the bottom as well. Pressure to achieve is more likely to be heaped on boys than on girls. Cognitive Influences Cognitive Developmental Theory This theory says children’s gender typing occurs after they have developed a concept of gender. Once they consistently conceive of themselves as male or female, children often organize their world on the basis of gender. Children use physical and behavioral clues to differentiate gender roles and to gendertype themselves in early development. They then select same-sex models to imitate. Gender Schema Theory States that an individual’s attention and behavior are guided by an internal motivation to conform to gender-based sociocultural standards and stereotypes. “Gender typing” occurs when individuals are ready to encode and organize information along the lines of what is considered appropriate for males and females in society. A general readiness to respond to and categorize information on the basis of culturally defined gender roles fuels ‹#› children’s gender-typing activities. This theory acknowledges, like Kohlberg’s cognitive developmental theory, that gender constancy is important along with other cognitive factors. Gender Constancy Gender constancy refers to the understanding that sex remains the same even though activities, clothing, and hair style might change. ‹#› Parenting: Nature and Nurture Two types of recent studies that effectively disentangle children’s heredity and their rearing experiences are: •Studies of the effects of rearing experiences on the behavior of children who differ in their temperament. •Studies that compare the effects of high- and low-risk environments on children of different vulnerability. Another way to examine links between parenting and child behavior is to study risk and resiliency in children. As with other areas of life-span development, evidence on the role of parenting shows that neither heredity alone nor environment alone is responsible for children’s development. Good Parenting Takes Time and Effort Good parenting takes a lot of time and effort. There is an unfortunate theme in today’s society which suggests that parenting can be done quickly. Compact discs are marketed for parents to simply play Mozart’s music in order to enrich young children’s brains. One-minute bedtime stories are also available, so parents can read to their children—but not for long. These items are seen as supporting parental neglect and reducing guilt of uninvested parents. Authoritarian Parenting A restrictive, punitive style in which parents exhort the child to follow their directions and to respect work and effort. These parents place firm limits and controls on the child and allow little verbal exchange. Authoritarian parenting is associated with children’s social incompetence. Children of authoritarian parents often are unhappy, fearful, anxious, fail to initiate activity, and have weak communication skills. Authoritative Parenting – usually the best method! This style encourages children to be independent but still places limits and controls on their actions. Extensive verbal give-and-take is allowed, and parents are warm and nurturant toward the child. Authoritative parenting is associated with children’s social competence. Children of authoritative parents are often cheerful, self-controlled and self-reliant, achievementoriented, maintain friendships with peers, cooperate with adults, and cope well with stress Neglectful Parenting A style in which the parent is very uninvolved in the child’s life. It is associated with children’s social incompetence, especially a lack of self-control. Children whose parents are neglectful frequently have low self-esteem, are immature, and may be alienated from the family. In adolescence, they may show patterns of truancy and delinquency. Indulgent Parenting A style of parenting in which parents are highly involved with their children, but place few demands or controls on them. Indulgent parenting is associated with children’s social incompetence, especially a lack of self-control. The result is that children never learn to control their own behavior and always expect to get their way. Children of indulgent parents may be aggressive, domineering, and noncompliant. ‹#› The Basics of Child Abuse It is estimated that as many as 500,000 children are physically abused every year. Experts believe that the view that parents who abuse their children are bad, sick, monstrous, sadistic individuals, who cause their children to suffer is too simple. The most common form of abuse is not a raging uncontrolled physical abuser, but an overwhelmed single mother in poverty who neglects the child. The Multifaceted Nature of Abuse Developmentalists are increasingly using the term child maltreatment rather than child abuse. The term does not have the same emotional impact of abuse, and acknowledges that maltreatment involves a number of different conditions: • Physical and sexual abuse • The fostering of delinquency • Lack of supervision • Medical, educational, and nutritional neglect • Drug and alcohol abuse Severity of Abuse Less than 1% of maltreated children die. Eleven percent suffer lifethreatening, disabling injuries. Almost 90% of cases suffer temporary physical injuries, although they tend to be experienced repeatedly. Neglected children, who suffer no physical injuries, often experience extensive, longterm psychological harm. The Cultural Context of Abuse The extensive violence that takes place in American culture is reflected in the occurrence of violence in the family. This contrasts with China, where physical punishment is rarely used as discipline and the incidence of child abuse is reported to be very low. Many abusive parents report not having sufficient resources or help from others. Community support systems are important in alleviating stressful family situations. Family Influences To understand abuse in the family, the interactions of all family members need to be considered, regardless of who actually performs the violence. About one-third of parents who were abused when they were young abuse their own children. Mothers who break out of the intergenerational transmission of abuse often have at least one warm, caring adult in their background, have a close, positive marital relationship, and have received therapy. Developmental Consequences of Abuse Maltreated children show poor emotion regulation. They show attachment problems, as they are typically categorized as disorganized. They have problems in peer relations due to their aggressiveness, avoidance, and aberrant responses to distress and positive approaches from peers. They have difficulty in adapting to school due to problematic interactions with teachers. Other psychological problems: anxiety, depression, conduct disorder, and delinquency. ‹#› Birth Order When differences in birth order are found, they are usually explained by variations in interactions with parents and siblings associated with the unique experiences of being in a particular position in the family. Given the differences in family dynamics involved in birth order, it is not surprising that firstborns and later-borns have different characteristics. Birth order alone is often not a good predictor of behavior. Firstborns Versus Later-Borns Parents have higher expectations for firstborns. They put more pressure on them for achievement and responsibility. They also interfere more with their activities. Firstborn children are more adult-oriented, helpful, conforming, anxious, and self-controlled than their siblings. Parents give more attention to firstborns; this is related to firstborns’ nurturant behavior. Due to the pressure placed on them, firstborns have more guilt, anxiety, and difficulty in coping. The Only Child Only children are often achievement-oriented and display a desirable personality, especially in comparison with later-borns and children from large families. They are very similar to first borns. The Middle Child Middle children tend to be peacemakers. They may be the class clown or get into mild trouble in a bid for attention. The Youngest Child The youngest child is often allowed to make more mistakes than the others because he/she’s “just a baby”. This child may grow up to be less responsible than the other children. ‹#› Working Parents Because household operations have become more efficient and family size has decreased in America, it is not certain that when both parents work outside the home that children actually receive less attention. Mothering does not always have a positive effect on the child. The rigid gender stereotyping perpetuated by the divisions of labor in the traditional family is not appropriate for the demands that will be made on children of either sex as adults. Effects of Divorce on Children Children’s Adjustment in Divorced Families Most researchers agree that children from divorced families show poorer adjustment than their counterparts in nondivorced families. Children in divorced families are more likely to have academic problems, to act out and be delinquent, and to experience depression and anxiety. They are likely to be less socially responsible, and to have less competent intimate relationships, as well as become sexually active earlier. They are more likely to take drugs and have low self-esteem. Other Findings The majority of children in divorced families do not have these problems. The weight of research underscores that most children competently cope with their parents’ divorce, but that significantly more children from divorced families have adjustment problems (20- 25%) than children from nondivorced families (10%). Should Parents Stay Together for the Sake of Their Children? If the stresses and disruptions in family relationships associated with an unhappy , conflictual marriage that erode the well-being of children are reduced by the move to a divorced, single-parent family, divorce may be advantageous. If the diminished resources and increased risks associated with divorce also are accompanied by inept parenting and sustained or increased conflict, the best choice for the children would be for an unhappy marriage to be retained. How Much Do Family Processes Matter in Divorced Families? Family processes matter a great deal in divorce. In the year following divorce, a disequilibrium, based partly on diminished parenting skills, occurs. By 2 years after the divorce, restabilization has occurred and parenting skills have improved. How Much Do Family Processes Matter in Divorced Families? About 25% of children from divorced families become disengaged from their families. This disengagement is higher for boys than girls. If there is a caring adult outside the home, the disengagement might be a positive experience. What Factors Are Involved in the Child’s Individual Risk and Vulnerability in a Divorced Family? • The child’s adjustment prior to the divorce • The child’s personality • The child’s temperament • The child’s gender • The custody situation What Role Does Socioeconomic Status Play in the Lives of Children in Divorced Families? Custodial mothers experience the loss of about one-quarter to one-half of their pre-divorce income, compared to a loss of only one-tenth by custodial fathers. The income loss for mothers is accompanied by increased workloads, high rates of job instability, and residential moves to less desirable neighborhoods with inferior schools. Cultural and Ethnic Variations in Families • The role of the father in the family • The extent to which support systems are available to families ‹#› • The ways in which children should be disciplined • Discipline styles (Praise and reasoning vs. criticism and physical punishment) • Views on education (Encouraged by both teachers and parents vs. teacher’s responsibility) ‹#› Peer Relations Good peer relations appear to be necessary for normal social development. Children who are rejected by peers are at risk for depression. Aggressive children are at risk for many problems. Play Play is a pleasurable activity that is engaged in for its own sake. It is exciting and pleasurable in itself because it satisfies our exploratory drive. Play’s Functions • Increases affiliation with peers and increases the opportunity for interaction • Releases tension • Advances cognitive development due to its symbolic and make-believe components • Provides an opportunity to practice roles children will assume later in life • Offers the possibilities of novelty, uncertainty, surprise, and incongruity Parten’s Classic Study of Play • Unoccupied play - the child is not engaging in play as it is commonly understood. • Solitary play - the child plays alone and independently of others. More frequent in 2- to 3-year-olds than older children. • Onlooker play - the child watches other children play, but may still talk and ask questions. • Parallel play - the child plays separately from others, but with similar toys or in a manner that mimics their play. • Associative play - involves social interaction with little or no organization. • Cooperative play - involves social interaction in a group with a sense of group identity and organized activity. ‹#› Sensorimotor and Practice Play • Sensorimotor play - behavior engaged in by infants to derive pleasure from exercising their existing sensorimotor schemas. • Practice play - the repetition of behavior when new skills are being learned or when physical or mental mastery and coordination of skills are required for games or sports. Sensorimotor play, which often involves practice play, is primarily confined to infancy, while practice play can be engaged in throughout life. Pretense/Symbolic Play Pretense/symbolic play - occurs when the child transforms the physical environment into a symbol. Between 9 and 30 months of age, children increase their use of objects in symbolic play. Experts consider the preschool years the “golden age” of pretense/symbolic play. In the early elementary school years, children’s interest often shift to games. Social Play Social play - involves social interaction with peers. Parten’s categories are oriented toward social play. Social play with peers increases dramatically during the preschool years. Rough-and-tumble play appears at this time. ‹#› Constructive Play Combines sensorimotor and practice repetitive activity with symbolic representation of ideas. Occurs when children engage in self-regulated creation or construction of a product or a problem solution. Increases in the preschool years. A frequent form of play in the elementary school years. Games Games - activities engaged in for pleasure. They include rules and often competition with one or more individuals. Games play a big part in the lives of elementary school children, with one study finding the highest incidence of game playing occurred between 10 and 12 years of age. ‹#› Television’s Many Roles • Negative influences: taking children away from homework, making them passive learners, teaching them stereotypes, providing them with violent models of aggression, and presenting them with unrealistic views of the world. • Positive influences: presenting motivating educational programs, increasing information about the world beyond children’s immediate environment, and providing models of prosocial behavior. Amount of Television Watching by Children In the 1990s, children averaged 11-28 hours of television per week, which is more than for any other activity except sleep. Considerably more children in the U.S. than their counterparts in other developed countries watch television for long periods. A special concern is the extent to which children are exposed to violence and aggression on television, even in cartoons. Effects of Television on Children’s Aggression Several studies have demonstrated the relationships between the amount of violence viewed on television and subsequent aggressive and violent behavior. These studies are correlational, thus the only conclusion can be that television ‹#› violence is associated with aggressive behavior, not that it causes aggressive behavior. Many experts argue that TV violence can induce aggressive or antisocial behavior in children. Effects of Television on Children’s Prosocial Behavior Television can teach children that it is better to behave in positive, prosocial ways than in negative, antisocial ways. Children who watched episodes of “Sesame Street” that reflected positive social interchanges copied the behaviors and, in later social situations, applied the prosocial lessons they had learned. Television and Cognitive Development Children’s greater attention to television and their less complete and more distorted understanding of what they view suggest that they may miss some of the positive aspects of television and be more vulnerable to its negative aspects. Regular television is negatively related to children’s creativity, however, educational programming may promote creativity and imagination due to its slower pace and coordination of video and audio input. Television is primarily a visual modality, thus verbal skills are enhanced more by aural or print exposure. ‹#›