31 Annual Conference on The First

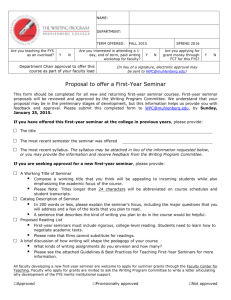

advertisement