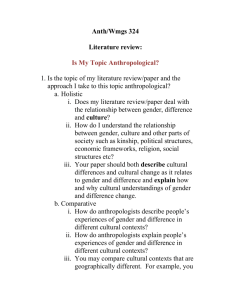

What Is Anthropology?

advertisement