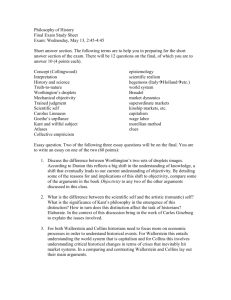

The Limits of Objectivity - The Tanner Lectures on Human Values

advertisement