child health Syphilis is on the increase: the implications for

advertisement

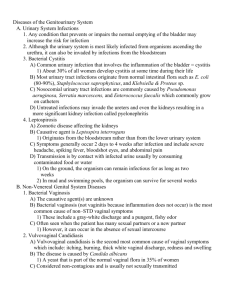

Downloaded from adc.bmj.com on 17 February 2009 Syphilis is on the increase: the implications for child health Rana Chakraborty and Suzanne Luck Arch. Dis. Child. 2008;93;105-109 doi:10.1136/adc.2006.103515 Updated information and services can be found at: http://adc.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/93/2/105 These include: References This article cites 37 articles, 10 of which can be accessed free at: http://adc.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/93/2/105#BIBL Rapid responses You can respond to this article at: http://adc.bmj.com/cgi/eletter-submit/93/2/105 Email alerting service Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article - sign up in the box at the top right corner of the article Notes To order reprints of this article go to: http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform To subscribe to Archives of Disease in Childhood go to: http://journals.bmj.com/subscriptions/ Downloaded from adc.bmj.com on 17 February 2009 Leading article Syphilis is on the increase: the implications for child health Rana Chakraborty, Suzanne Luck Regardless of origins, syphilis has affected Europeans over many centuries. The first well-documented outbreak occurred in Naples in 1494, rapidly swept throughout Europe and was associated with a myriad of presenting signs and symptoms and a high mortality rate.1 The condition was once a leading cause of dementia and in the pre-antibiotic era caused one out of five of all admissions to psychiatric institutions in the USA.2 In 1943 Mahoney and co-workers first treated cases of syphilis with penicillin. This drug has remained the mainstay of treatment since that time.3 TRANSMISSION Horizontal transmission among adolescents and adults is primarily sexual, although anecdotal reports cite kissing, contact with infected secretions and blood transfusion as potential sources of acquisition and transmission.4 Transmission to the fetus is usually via the placenta, but may occur during delivery in the presence of maternal genital lesions. The risk of vertical transmission of syphilis from an infected untreated mother decreases as maternal disease progresses, ranging from 70–100% for primary syphilis and 40% for early latent syphilis to 10% for late latent disease (early and late latent syphilis occurring less than or more than 1 year after initial infection in adults, respectively).3 5 Although unusual, transmission to newborns from mothers with tertiary syphilis has also been reported.6 Thus, the longer the interval between infection and pregnancy, the more benign is the outcome in the infant (Kassowitz’s law).6 EPIDEMIOLOGY Syphilis is common in the developing world with localised prevalence in pregnant women varying widely from 2.5% in Burkina Faso to 17.4% in Cameroon.7 Department of Child Health, St George’s Hospital, London, UK Correspondence to: Dr R Chakraborty, Department of Child Health, St George’s Hospital, 5th Floor, Lanesborough Wing, Blackshaw Road, Tooting, London SW17 0QT, UK; rchakrab@sgul.ac.uk Arch Dis Child February 2008 Vol 93 No 2 However, such data may be skewed by high numbers of false-positive assays. Data on sexually transmitted infections have been collected in the UK since 1917; such infections are currently reported by genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics to the Health Protection Agency (HPA) by KC60 statutory notification in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and by ISD(D)5/STISS returns in Scotland. These official figures may therefore be an underestimation of the burden of congenital syphilis if diagnoses are made outside the GUM setting. Since 1998 a sharp increase in syphilis diagnoses has been documented among heterosexual populations8 9 and men who have sex with men (MSM) (fig 1). In Manchester and London, this increase resulted in the introduction of enhanced surveillance in 1999 and 2001, respectively, which was subsequently extended nationally. Among women, syphilis primarily affects 16–34-year-olds who are also those most likely to conceive (fig 2), mandating screening for syphilis antenatally. Localised outbreaks in the UK have been associated with sex workers and cocaine usage.8 10 An earlier study performed by the British Paediatric Surveillance Unit (BPSU) commented on an over-representation of pregnant women from ethnic minorities born outside the UK treated for syphilis in the Thames region.11 Recent reports have raised concerns that current antenatal testing may be inadequate for the identification and treatment of women at risk.11–13 These concerns are reinforced by recent data from the HPA, which identified 36 cases of congenital syphilis in the UK in 2005, the highest number in 10 years.14 CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS In pregnant women untreated or inadequately treated syphilis is associated with prematurity, low birth weight, nonimmune hydrops and intrauterine death. It has been estimated that at least twothirds of all fetuses of mothers with infectious syphilis are in some way affected.15 The WHO estimates that 1 million pregnancies are affected by syphilis worldwide. Of these 460 000 will result in abortion or perinatal death, 270 000 infants will be born prematurely or with low birth weight, and 270 000 will be born with stigmata of congenital syphilis.16 Most affected infants are asymptomatic at birth with two-thirds developing symptoms by 3–8 weeks. Almost all exhibit symptoms by 3 months of age.17 The pathological features in all stages of syphilis reflect vasculitis and its consequences, namely necrosis and fibrosis. The gummatous stage is characterised by chronic granulomatous inflammation. The syndromes of congenital syphilis can be classified as either early or late. Early features are similar to the manifestations of secondary syphilis in adults; late onset is defined as symptoms developing in children older than 2 years of age and characterised by gumma formation in tissues including bone, cardiac and the nervous system. The early manifestations of congenital syphilis The symptoms of early syphilis can be varied. ‘‘Snuffles’’ or persistent rhinitis is often the earliest presenting symptom, occurring in 4–22% of newborns.18 This discharge can take many forms and is highly infectious. Necrotising funisitis, a deep-seated infection of the umbilical cord, was considered to be diagnostic of congenital syphilis. It almost always occurs in premature neonates and is associated with a high incidence of intrauterine or perinatal death.19 Other common, but often nonspecific, symptoms of congenital syphilis include non-tender generalised lymphadenopathy, conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia and hepatosplenomegaly (table 1).20 21 Glomerulonephritis resulting in nephrotic syndrome may also occur. The rash in early syphilis is classically a vesiculobullous or maculopapular rash occurring on the palms and soles and may be associated with desquamation. Other rashes including erythema multiforme have been reported.20 22 Asymptomatic cerebrospinal fluid changes (elevated protein, positive Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test (VDRL)) may be found in 80% of infants,23 but acute syphilitic meningitis occurs rarely.24 Bony lesions occur commonly and present in the first 8 months of life. Radiographic abnormalities may be seen in 20% of babies with asymptomatic infection necessitating prompt radiological assessment of all exposed infants. The bones most often affected include the tibia, the tubular bones of the hands and feet and, more rarely, the skull and 105 Downloaded from adc.bmj.com on 17 February 2009 Leading article Figure 1 Numbers of diagnoses of syphilis (primary, secondary and early latent) by sex, GUM clinics, England, Wales and Scotland, 1931–2005. Equivalent Scottish data are not available prior to 1945. Northern Ireland data from 1931 to 2000 are incomplete and have been excluded. Data source: KC60 statutory returns and ISD(D)5\STISS data. GUM, genitourinary medicine. clavicles. Radiographic examination of bones can reveal irregular epiphyseal lines, decalcification of subchondral bone, cupping of the diaphysis, irregularity of cartilage adjacent to the epiphysis and periosteal thickening. The typical Wimberger’s lines seen during early syphilis reflect metaphyseal destruction secondary to focal erosion of the inner aspect of the proximal tibia.21 25 Osteochondritis or Parrot’s pseudo-paralysis is the most common and earliest lesion characterised by an asymmetric, painful, flaccid paralysis of the upper limbs and knees which can be confused with Erb’s palsy.26 Diaphyseal periostitis is asymptomatic and radiographic changes are often not seen until after 3 months of age. The late manifestations of congenital syphilis Late congenital syphilis occurs in children over the age of 2, but most often presents in puberty.15 Late syphilis can affect many organ systems, although the sites most often involved include the bones, teeth and nervous system. A poor response to intensive treatment is often documented during the management of these late manifestations.27 Some 25–33% of infants with untreated congenital syphilis have asymptomatic neurosyphilis once they are more than 2 years old.24 Symptomatic neurosyphilis, tabes dorsalis and cerebrovascular lesions develop rarely, with juvenile paresis developing in 1–5% of children/adolescents with congenital syphilis.24 When symptomatic, neurosyphilis can result in eighth nerve deafness. The onset of deafness is generally sudden and occurs at 8–10 years of age; associated with notched incisors and interstitial keratitis it forms part of the classical Hutchinson’s triad. Other ocular lesions include iridocyclitis and chorioretinitis. Following the changes seen in early syphilis, granulation tissue replaces bone marrow cortex and pathological fractures may result later in the disease. Early bony changes can be completely reversed with timely treatment but if untreated the characteristic permanent deformities associated with congenital syphilis develop, such as saddle nose, palatal erosions, short maxillae, protruding mandible, frontal bossing, and sabre tibia. Clutton’s joints (hydrarthrosis) involving the knees or elbows may develop between 8 and 15 years of age. Other characteristic signs of congenital syphilis are mulberry molars and fissuring around the mouth (rhagades). Rashes can also be seen in late onset congenital syphilis but are more localised in nature and morphologically distinct from those seen in early syphilis, consisting of nodules and gummata. DIAGNOSIS The gold standard for diagnosis of syphilis is the rabbit infectivity test (RIT) whereby the body fluid of a person with suspected infection is injected into a rabbit. Only one organism needs to be present to confirm diagnosis, however this test has obvious limitations and is not used routinely in clinical practice in the UK. Definitive diagnosis of syphilis more usually involves viewing the classical spirochaetes of Treponema pallidum on darkfield microscopy of mucosal lesions, exudates, lymph nodes or placental tissue. This test has a low sensitivity (,105 organisms/ml), however, and relies on fresh, good quality specimens. In addition, it is not specific when used for examining oral lesions where treponemal species are part of the normal oral flora. The use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect T pallidum in orogenital lesions and CSF offers the possibility of a more sensitive and specific means of diagnosing syphilis.28 29 Neonates have been reported to be more likely to have syphilis detectable in the blood or CSF, making PCR to detect T pallidum of interest for the future diagnosis of congenital syphilis, and in particular early detection of neurosyphilis.30 Antenatal testing Figure 2 Rates of diagnoses of infectious syphilis (primary and secondary) by sex and age group, GUM clinics, United Kingdom, 1996–2005. Data source: KC60 statutory returns and ISD(D)\5 data. 106 Guidelines have recently been published relating to the diagnosis of syphilis in adults and serology remains the mainstay of laboratory testing for syphilis.31 Effective prevention of congenital syphilis depends on the identification of active infection in pregnant women by routine Arch Dis Child February 2008 Vol 93 No 2 Downloaded from adc.bmj.com on 17 February 2009 Leading article Table 1 Incidence of symptoms in early and late congenital syphilis Percentage of cases20 21 Early Abnormal bone x ray Hepatomegaly Splenomegaly Petechiae Skin lesions Anaemia Lymphadenopathy Jaundice Pseudoparalysis Snuffles CSF abnormalities Late Frontal bossing Palatal deformation Dental dystrophies Interstitial keratitis Abnormal bone x ray Nasal deformity Eighth nerve deafness Neurosyphilis Joint disorder 33–95% 51–56% 49% 41% 35–44% 34% 32% 30% 28% 23% 25% 30–87% 76% 55% 20–50% 30–46% 10–30% 3–4% 1–5% 1–3% screening during antenatal visits and near the time of delivery with a non-treponemal test (VDRL or rapid plasma reagin (RPR)). These tests are quantitative and correlate with disease activity and response to therapy. Non-treponemal tests can be falsely negative with early primary syphilis, latent acquired syphilis of long duration and late congenital syphilis. A non-treponemal test performed on serum samples containing high concentrations of antibody against T pallidum can be weakly reactive or falsely negative; this reaction is termed the prozone phenomenon. Falsepositive results can be secondary to viral infections (infectious mononucleosis, hepatitis, varicella, measles), lymphoma, tuberculosis, malaria, endocarditis, connective tissue disease, pregnancy, laboratory error, or Wharton jelly contamination when cord blood specimens are used.32 For women treated during pregnancy, follow-up serological testing is necessary to assess the efficacy of therapy demonstrated by a fourfold decrease in nontreponemal titres. These usually become non-reactive 1 year after prompt treatment of primary or secondary infection if the initial titre is low (,1:8) and within 2 years with congenital infection or if the initial titre is high. Differentiating treated syphilis from active (re)infection may be difficult in the absence of increasing titres. To exclude a false-positive non-treponemal test, serology should be sent for Arch Dis Child February 2008 Vol 93 No 2 confirmatory treponemal antibody detection by fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) or T pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA). Treatment should not be delayed while awaiting the results of the treponemal test if the patient is symptomatic or at high risk of infection. Treponemal test antibody titres remain reactive for life even after successful therapy, correlate poorly with disease activity and should therefore not be used to assess response to therapy. Treponemal tests may not be specific for syphilis, since positive reactions variably occur in patients with other spirochetal infections, including yaws, pinta, leptospirosis, ratbite fever, relapsing fever and Lyme disease. The combination of non-treponemal and treponemal tests provides sensitive and specific screening for all stages of syphilis but requires subjective interpretation and cannot readily be automated.33 With the recent commercial availability of enzyme immunoassays (EIAs), the nontreponemal and treponemal combination is increasingly being replaced in UK diagnostic microbiology laboratories by assays detecting treponemal IgG or IgG and IgM. Advantages include the production of objective results, the ability to link EIA plate readers directly to laboratory computer systems, and the facility for automation.34 A quantitative non-treponemal test and serology for specific antitreponemal IgM provides a baseline for monitoring the effect of therapy. IgM becomes undetectable within 3–9 months after adequate treatment of early syphilis but may persist for up to 18 months after treatment of late disease.35 Although the treponemal IgG EIA has not been as widely adopted in the USA,31 there are published data showing that screening with recombinant antigen-based treponemal IgG and IgM has comparable sensitivity and specificity compared to the non-treponemal and treponemal combination,36–38 and may be useful for detecting treponemal antibody in HIV-infected patients.39 Evaluation of newborn infants with perinatal exposure to syphilis All infants born to seropositive mothers should be considered to be exposed to syphilis unless full investigation of the mother shows other explanations for the serological findings and/or evidence of complete treatment and response to this treatment. Where possible the placenta and/or umbilical cord should be sent for pathological examination and dark ground microscopy, if this is available. Serology should be sent for quantitative non-treponemal tests using the same assay as that performed on the mother to enable comparison of titres. Cord blood is inadequate for screening since sera can be non-reactive even when the mother is seropositive and contamination with maternal blood may occur.40 A guide for interpretation of the results of nontreponemal and treponemal serological tests is given in table 2.41 Where combinations of diagnostic tests other than those referred to above are being used, we recommend local collaboration and discussion antenatally regarding planned follow-up for the neonate. Anti-treponemal IgG measured in the infant can be transplacentally acquired from the mother and persist for up to 18 months, and so is not of use in the initial evaluation of an infant for congenital infection. Detection of specific anti-treponemal IgM may also be useful in the diagnosis of congenital infection, but a negative result around the time of delivery does not exclude congenital infection. Serological follow-up is indicated and should include repeat IgM testing, and quantitative nontreponemal and treponemal serology to demonstrate loss of passive maternal antibody. An exposed infant should be evaluated for active syphilis and considered at high risk for infection if: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. The infant is symptomatic. Titre of maternal non-treponemal serology (eg, VDRL, RPR) has increased fourfold. Infant non-treponemal titre is fourfold greater than maternal titre. Maternal syphilis was untreated or inadequately treated during pregnancy with insufficient serological follow-up. Maternal syphilis was treated with a non-penicillin regimen. After treatment of maternal syphilis (with an appropriate penicillin regimen), the expected decrease in nontreponemal antibody titre after therapy did not occur. Treatment for maternal syphilis was commenced less than 1 month before delivery. If the situation is unclear, then repeat maternal and infant bloods should be taken at birth, a full evaluation of the baby carried out and serious consideration given to treatment of the neonate while results are awaited. If treatment is not instituted, clinicians should be certain 107 Downloaded from adc.bmj.com on 17 February 2009 Leading article Table 2 Guide for interpretation of syphilis serological test results of mothers and their infants Non-treponemal test (VDRL, RPR, EIA, ART) Treponemal test (MHA-TP, FTA-ABS) Mother Infant Mother Infant Interpretation – + + – + +/– – – + – – + + – + – + + + + No syphilis or incubating syphilis in the mother and infant No syphilis in mother (false-positive non-treponemal test with passive transfer to infant) Maternal syphilis with possible infant infection; or mother treated for syphilis during pregnancy; or mother with latent syphilis and possible infection of the infant Recent or previous syphilis in the mother; possible infection in the infant Mother successfully treated for syphilis before or early in pregnancy; or mother with Lyme disease, yaws or pinta (ie, false–positive serology) ART, automated reagin test; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; FTA-ABS, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed; MHA-TP, microhaemagglutination assay – Treponema pallidum; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory. that rigorous follow-up will be possible and attendance ensured. In women who come from areas where other treponemal infections are endemic (such as pinta or yaws), babies should be treated as if they have congenital syphilis since it is impossible using standard serological tests to differentiate between these infections. If maternal HIV is present, then the risk of transmission of syphilis should be considered to be even greater and a lower threshold for treatment adopted. In addition to blood for treponemal and non-treponemal testing, the evaluation should also include liver function tests, long bone x rays, CSF specimen for VDRL test and analysis for the detection of white cells and elevated protein, and ophthalmic assessment. A negative VDRL on CSF does not exclude congenital neurosyphilis. If a case of congenital syphilis is suspected, evaluation of any previously uninvestigated siblings should also be considered. TREATMENT Parenteral penicillin G is the only documented effective therapy for patients who have neurosyphilis, congenital syphilis or syphilis during pregnancy. Aqueous crystalline penicillin G is preferred over procaine penicillin G because adequate CSF concentrations may not be achieved with the latter. If more than 1 day of therapy is missed, it has been recommended that the entire course should be restarted, although there is no recent evidence to support this recommendation. Newborn infants In newborn infants, the dose for aqueous crystalline penicillin G is 100 000– 150 000 U/kg per day, administered as 50 000 U/kg per dose, intravenously, every 12 h during the first 7 days of life and every 8 h thereafter for a total of 10 days. Procaine penicillin G is administered in a single dose at 50 000 U/kg per day, intramuscularly, for 10 days. These 108 recommendations are based on chronological, not gestational, age. Older infants and children Infants older than 4 weeks of age who possibly have congenital syphilis or who have neurological involvement should be treated with aqueous crystalline penicillin, 200 000–300 000 U/kg per day, intravenously (administered every 6 h), for 10 days. This regimen also should be used to treat children older than 1 year of age who have late and previously untreated congenital syphilis.41 During pregnancy UK guidelines are already available and patients should be treated with penicillin according to the dosage schedules appropriate for the stage of syphilis as recommended for non-pregnant patients.42 Penicillin-allergic pregnant women should be treated with penicillin after desensitisation. While awaiting penicillin desensitisation, erythromycin (or other nonpenicillin regimes) should be used. Evidence that non-penicillin regimes are effective in the treatment of congenital syphilis is not currently available, however, meaning that infants should be treated at birth as if mother had received no treatment if such regimes are used. FOLLOW-UP Treated infants should be followed up at 3, 6 and 12 months of age until serologic non-treponemal tests become non-reactive or the titre has decreased fourfold. With adequate treatment or in cases where antibody is transplacentally acquired in the absence of congenital infection, non-treponemal antibody titres should decrease by 3 months of age and be non-reactive by 6 months of age. At 6– 12 months of age previously treated infants with increasing or persistent titres should be evaluated, including CSF examination, and treated with a further 10-day course of parenteral penicillin G. Treated infants with congenital neurosyphilis should undergo repeated clinical evaluation and CSF examination at 6month intervals until their CSF examination is normal. A persistently reactive VDRL test of CSF is an indication for retreatment.41 In untreated babies with no symptoms of congenital syphilis who are documented to have a non-treponemal antibody titre at least fourfold less than their mothers at birth and whose mother was fully treated and evaluated antenatally (including follow-up testing to confirm successful treatment), no further followup is required. If there is any uncertainty regarding the completeness of antenatal follow-up or neonatal serology then the baby should be reviewed and further samples sent for non-treponemal antibody testing at 3 and 6 months of age. A full re-evaluation should be carried out if titres have not decreased by 6 months of age. A sample for treponemal antibody titres should then be sent at 12 months of age; in most cases they will no longer be detectable by this age if passively acquired. CONCLUSION In this article we have reviewed the management of maternal and congenital syphilis. At a time when this disease has re-emerged in the UK, we hope that the review will assist clinicians in familiarising themselves again with the subtleties of this age-old affliction. Despite the introduction of effective treatment and the availability of diagnostic testing in the mid-20th century, syphilis still remains a national health issue: ‘‘…(s)he who knows syphilis knows the more things change the more they stay the same’’! Competing interests: None. Accepted 4 September 2007 Arch Dis Child 2008;93:105–109. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.103515 Arch Dis Child February 2008 Vol 93 No 2 Downloaded from adc.bmj.com on 17 February 2009 Leading article REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. Rothschild BM. History of syphilis. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1454–63. Hutchinson CM, Hook EW 3rd. Syphilis in adults. Med Clin North Am 1990;74(6):1389–416. Ingraham NR Jr. The value of penicillin alone in the prevention and treatment of congenital syphilis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1950;31(Suppl 24):60– 87. Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Microbiol Rev 1999;12(2):187– 209. Fiumara N, Fleming W, Dowing JG, et al. The incidence of prenatal syphilis at the Boston City Hospital. N Engl J Med 1952;247:48–52. Evans HE, Frenkel LD. Congenital syphilis. Clin Perinatol 1994;21(1):149–62. WHO. Global prevalence and incidence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections. Geneva: WHO, 2001. http://www.who.int/docstore/hiv/GRSTI/ 005.htm (accessed 29 October 2007). Righarts AA, Simms I, Wallace L, et al. Syphilis surveillance and epidemiology in the United Kingdom. Euro Surveill 2004;9(12):21–5. Palfreeman AJ, Moussa RA. Syphilis in the fens. Sex Transm Infect 2001;77(5):314–15. CDSC. Syphilis in Bristol 1997–8: an update. Commun Dis Rep CDR Wkly 1998;8(413):416. Hurtig AK, Nicoll A, Carne C, et al. Syphilis in pregnant women and their children in the United Kingdom: results from national clinician reporting surveys 1994–7. BMJ 1998;317:1617–19. Cross A, Luck S, Patey R, et al. Syphilis in London circa 2004: new challenges from an old disease. Arch Dis Child 2005;90(10):1045–6. Sothinathan U, Hannam S, Fowler A, et al. Detection and follow up of infants at risk of congenital syphilis. Arch Dis Child 2006;91(7):620. Health Protection Agency. All new diagnoses made at GUM clinics: 1996–2005 United Kingdom and country specific tables, page 4. http:// www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/hiv_and_sti/ epidemiology/datatables2005.htm (accessed 30 October 2007). Walker DG, Walker GJA. Forgotten but not gone: the continuing scourge of congenital syphilis. Lancet Infect Dis 2002;2:432–6. Arch Dis Child February 2008 Vol 93 No 2 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. Walker DG, Walker GJ. Prevention of congenital syphilis--time for action. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82(6):401. Gurlek A, Alaybeyoglu NY, Demir CY, et al. The continuing scourge of congenital syphilis in the 21st century: a case report. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2005;69:1117–21. Chawla V, Pandit PB, Nkrumah FK. Congenital syphilis in the newborn. Arch Dis Child 1998;63:1393–4. Jacques SM, Qureshi F. Necrotizing funisitis: a study of 45 cases. Hum Pathol 1992;23:1278–83. Sangtawesin V, Lertsutthiwong W, Kanjanapptanakul W. Outcome of maternal syphilis at Rajavithi Hospital on offsprings. J Med Assoc Thai 2005;88:1519–25. Hira SK, Bhat GJ, Patel JB, et al. Early congenital syphilis: clinico-radiologic features in 202 patients. Sex Transm Dis 1985;12:177–83. Wu CC, Tsai CN, Wong WR, et al. Early congenital syphilis and erythema multiforme-like bullous targetoid lesions in a 1-day-old newborn: detection of Treponema pallidum genomic DNA from the targetoid plaque using nested polymerase chain reaction. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55(2 Suppl):S11–15. Platou RV. Treatment of congenital syphilis with penicillin. Adv Pediatr 1949;4:39–86. Wile U, Mundt LK. Congenital syphilis: a statistical study with special regard to sex incidence. Am J Syphilis Gonorrhea Vener Dis 1942;26:70–83. Brion LP, Manuli M, Rai B, et al. Long-bone radiographic abnormalities as a sign of active congenital syphilis in asymptomatic newborns. Pediatrics 1991;88:1037–40. Sobel J. Antenatal and neonatal protection of the infant. Arch Pediatr 1926;43:448–65. Uchiyama K, Tsuchihara K, Horimoto T, et al. Phthisis bulbi caused by late congenital syphilis untreated until adulthood. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;139(3):545–7. Liu H, Rodes B, Chen C-Y, et al. New tests for syphilis: rational design of a PCR method for detection of Treponema pallidum in clinical specimens using unique regions of the DNA Polymerase I gene. J Clin Microbiol 2001;39:1941–6. Leslie DE, Azzaro F, Karapanagiotidis T, et al. Development of a real-time PCR assay to detect Treponema pallidum in clinical specimens and assessment of the assay’s performance by 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. comparison with serological testing. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:93–6. Michelow IC, Wendel GD, Norgard VM, et al. Central nervous system infection in congenital syphilis. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1792–8. Lewis DA, Young H. Syphilis. Sex Transm Infect 2006;82(Suppl IV):13–15. Hook EWIII, Marra CM. Acquired syphilis in adults. N Engl J Med 1992;326:1060–9. Young H. Syphilis serology. Dermatol Clin 1998;16:691–8. Egglestone SI, Turner AJ. Serological diagnosis of syphilis. PHLS Syphilis Serology Working Group. Commun Dis Public Health 2000;3(3):158–62. Luger AFH. Serological diagnosis of syphilis: current methods. In: Young H, McMillan A, eds. Immunological diagnosis of sexually transmitted diseases. New York: Marcel Decker, 1988:249–74. Young H, Moyes A, McMillan A, et al. Screening for treponemal infection by a new enzyme immunoassay. Genitourin Med 1989;65:72–8. Young H, Moyes A, McMillan A, et al. Enzyme immunoassay for antitreponemal IgG: screening or confirmatory test? J Clin Pathol 1992;45:37–41. Young H, Moyes A, Seagar L, et al. Novel recombinant-antigen enzyme immunoassay for the serological diagnosis of syphilis. J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:913–17. Young H, Moyes A, Ross JCD. Markers of past syphilis in HIV infection comparing Captia Syphilis G anti-treponemal IgG enzyme immunoassay with other treponemal antigen tests. Int J STD AIDS 1995;6:101–4. Chhabra RS, Brion LP, Castro M, et al. Comparison of maternal sera, cord blood and neonatal sera for detecting presumptive congenital syphilis: relationship with maternal treatment. Pediatrics 1994;91:88–91. American Academy of Pediatrics. Syphilis. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book 2000: report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 25th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000:547. Clinical Effectiveness Group (Association for Genitourinary Medicine and the Medical Society for the Study of Venereal Diseases). UK National Guidelines on the Management of Early Syphilis. http://www.bashh.org/guidelines/2002/ early$final0502.pdf (accessed 30 October 2007). 109