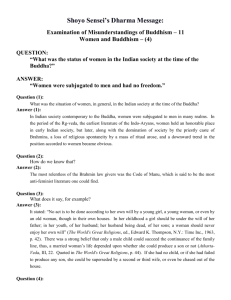

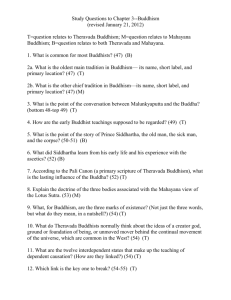

Aspects of Buddhism in Indian History

advertisement