Social Interaction and Everyday Life

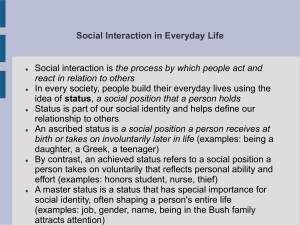

advertisement

CHAPTER COMMENTARY The importance of focusing on small-scale and everyday aspects of social life is demonstrated through this chapter. It is through such study that the importance of routine in the maintenance of social life becomes evident – the constant daily creativity of making and remaking the social world; the links between these everyday practices and the reproduction of social institutions. This subject matter provides ample opportunity to link the study of sociology to students’ own life experience and is often great fun to teach. The study of small-scale social interaction lies at the interface of sociological and psychological approaches and provides an important opportunity to draw students away from the tendency to speculate on personality and motivation and to concentrate on the more explicitly social aspects of interactions. The discussion starts from the management of civil inattention and moves to consider nonverbal communication as a universal feature of human communication. Cross-cultural similarities in the facial expression of emotional states are presented, as is the idea that these are modified by each society into forms acceptable in that culture. Elias’s argument that the face is a sounding board for emotional expression is discussed. That individuals constantly monitor and control their bodies to avoid the transgression of social norms is highlighted. The gendered dimensions of small-scale interactions and body language are explored through Young’s influential article, ‘Throwing Like a Girl’ (1980). In both private and public space such interactions demonstrate not only gendered difference but also gendered inequality. At this point Judith Butler’s theory of the performativity of gender identities is explained, providing a forward link to Chapters 10 and 16 on Families and Intimate Relationships, and Gender and Sexuality respectively. The section is rounded off with a short section covering the embodiment of identities using Goffman’s work on social stigma. The chapter now moves on to place the social actor’s self-management in the changing contexts of social interaction. Starting from Goffman’s distinction between unfocused interaction and focused interaction it becomes possible to see how social life is not a given but an achievement. Goffman is given Classic Study status on pages 313-4. A day is presented as a succession of focused encounters which are marked off from each other, and periods of unfocused interaction by verbal and non-verbal cues which bracket the episodes. Central to this dramaturgical model is the core sociological concept of social role defined as ‘socially defined expectations that a person in a given status, or social position, follows’. The distinction is drawn between ascribed and achieved status and the importance of the master status. Encounters are seen as the presentation of the social role, acted out in the © Polity Press 2013 This file should be used solely for the purpose of review and must not be otherwise stored, duplicated, copied or sold Social Interaction and Everyday Life front region, where the normal flow of social interaction is maintained through personal impression management. The preparation for such encounters takes place backstage in the back regions of social life. The management of the pelvic examination is presented as a case study to illustrate elements of Goffman’s approach. The collective nature of performance is also considered through the example of young women using the women’s toilet as a site for team talks and performance planning. Moving on to verbal communication and specifically talk, the chapter turns to the work of Harold Garfinkel and the analysis of conversation, presented as a Classic Study in this field. Ethnomethodology is defined on page 317 as: ‘the study of the “ethnomethods” – the folk, or lay, methods – people use to make sense of what others do, and particularly what they say’. The emphasis upon meaning is linked to the notion of shared understandings as the underpinning of all conversation. The examples discussed range from the specific background knowledge shared by friends to the more widely culturally shared ‘background expectancies’ revealed by Garfinkel’s experiments. Using conversation analysis techniques, actual instances of interaction in a New York street between black male street-dwellers and women pedestrians are analysed. In these interactions the normal cues and conventions for opening and closing conversations are ignored by the men, forcing the women into a position of being ‘technically rude’. Cases like these where a subordinate person breaks the rules of interaction to disquiet a more powerful person are termed interactional vandalism and whilst conducted through the micro-rules of interaction they only make sense within a broader explanatory context of class, ethnic and gender inequalities. The cultural specificity and social function of utterances is returned to via a discussion of involuntary response cries such as ‘Oops!’ These cries bridge the temporary disturbance in the taken-for-granted quality of social life created by a mistake and assure all social actors that the individual is a competent and reliable social being. Sociology has become increasingly aware that time and space do not simply form the backdrop to the performance of social life but form integral parts of it. At the most micro of levels the management of space marks the management of social relationships. Close bodily proximity marks intimate space permitted to lovers and family, personal space and is reserved for few social relationships, social distance marks the space for most focused encounters, whilst public distance marks a clear distinction between a social performer and the audience. Space on a larger scale also forms part of the fabric of social life as different areas of homes, urban areas, countries and even the globe are regionalized, providing locations for different social acts. Similarly, the same space is often used differently at different times. Again, the home provides examples of this, but time patterns are equally evident in institutions such as hospitals. The social relationships of space and time are significantly different in modern and traditional societies. The management of complex social and economic relationships led to the dominance of clock time and the adoption in 1884 of world standard time. In recent years it has often been argued that space has been annihilated through time, as developments in electronics have made communications across the globe instantaneous. Yet this is not an annihilation of space–time but a modification of its dimensions. The boundaries of social space and the techniques and rules through which it is maintained are in a state of constant transformation. New means of electronic communication present new forums for the enactment of social space and interaction. Similarly, the rules of interaction are not the same in the traditional society of the !Kung as those we are used to in modern societies, but there are still rules. Equally, the experience of tourism brings into contact different cultural 66 Social Interaction and Everyday Life and interactional expectations: visitors to the Middle East who experience an encroachment upon their personal space are experiencing different rules of spatiality. These examples can be used to illustrate the importance of social constructionism as an approach which reveals the socially constructed nature of our collective realities. The new rules of trust being enacted on the Internet are another marker of the adaptability of interactional processes, illustrated with the box on ‘creation and maintenance of e-trust’ on page 325. The Internet provides communication and interactional opportunities which are also defining their own social norms or netiquette. However, individuals still show a compulsion of proximity and great resistance to fully replacing face-to-face communications with the electronically mediated. TEACHING TOPICS 1. The micro and the macro The chapter provides a number of examples which signpost the relationship between smallscale social interactions and broader structural issues. Students can usefully be referred to the discussion of structure and action in Chapter 3 (pages 87-91) and this topic offers a springboard to further consideration of this issue. The inclusion of examples from different cultures, including traditional society and the globalized online space of the Internet, open up the relationship between instances of interaction and the cultures within which they are located. Examples of street interactions link to questions of power within modern societies. 2. Shared understandings and the possibility of communication It is stressed throughout the chapter that talk is both ‘situated’, that is, tied to the particular context of a particular conversation, and rooted in a broader set of shared understandings about the nature of the social world. This seeming paradox is one that has dogged the relationship between ethnomethodology and sociology but which is accepted rather than analysed here. This topic provides students with the opportunity to look more closely at everyday talk as a social accomplishment. 3. The presentation of the self in everyday life The chapter extensively draws on the work of Erving Goffman, and this topic is included to reinforce that material. The dramaturgical model is one which non-specialist sociologists working in vocational settings often find useful in their work. For such students this is a particularly useful topic, which can be tailored to their interests and experiences. ACTIVITIES Activity 1: The micro and the macro Read the section ‘Why study everyday life?’ (pages 302-3), which introduces the relationship between micro- and macro sociologies. The chapter also contains three extended examples of interaction on the street: Women and men in public (pages 305-7), Interactional ‘vandalism’ (pages 317-20) and Street encounters (pages 311-2). These interactions are only possible because city streets exist; they are small-scale interactions located within the broader context of the macro-structures of urbanization which produce a society where individuals are constantly in contact with strangers. Social Interaction and Everyday Life A. An early sociological exploration of the impact of city life comes from the sociologist George Simmel (1858–1918), who once asserted that ‘Society is the name for a number of individuals, connected by interaction.’ Although cities had existed since antiquity, the growth of large modern cities occurred mainly during the nineteenth century. In the closing years of that century Simmel studied the bustling, thriving city of Berlin and noted the changes upon the individual which the new forms of interaction necessitated by city life had brought about. This work is discussed in chapter 6 of Sociology. Here is part of his account of the development of ‘the Metropolitan character’: When one inquires about the products of the specifically modern aspects of contemporary life with reference to their inner meaning – when, so to speak, one examines the body of culture with reference to the soul, as I am to do concerning the metropolis today – the answer will require the investigation of the relationship which such a social structure promotes between the individual aspects of life and those which transcend the existence of single individuals. It will require the investigation of the adaptions made by the personality in its adjustments to the forces that lie outside of it. The psychological foundation, upon which the metropolitan individuality is erected, is the intensification of emotional life due to the swift and continuous shift of external and internal stimuli. Man is a creature whose existence is dependent on differences, i.e., his mind is stimulated by the difference between present impressions and those which have preceded. Lasting impressions, the slightness in their differences, the habituated regularity of their course and contrasts between them, consume, so to speak, less mental energy than the rapid telescoping of changing images, pronounced differences within what is grasped at a single glance, and the unexpectedness of violent stimuli. To the extent that the metropolis creates these psychological conditions – with every crossing of the street, with the tempo and multiplicity of economic, occupational and social life – it creates the sensory foundations of mental life, and in the degree of awareness necessitated by our organisation as creatures dependent on differences, a deep contrast with the slower, more habitual, more smoothly flowing rhythm of the sensory-mental phase of small town and rural existence. (Georg Simmel, ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’, in D. N. Levine (ed.), Georg Simmel On Individuality and Social Structure, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971[1903], p. 325) 1. Given Simmel’s view of modern city life, how does the example of interactional vandalism fit his account? 2. The box on pages 311-2 of Sociology describes the processes by which people negotiate a city street. Why are interactions based upon generalizations and stereotypes more likely in a city than a small village? How does this compare to the interactions in !Kung society? B. Early sociologists such as Simmel rarely placed gender at the centre of their analysis, yet the examples we have looked at all clearly demonstrate that gender is a fundamental component of social interaction. In Chapter 3 it is argued that we ‘actively make and remake social structures during the course of our everyday activities’. 1. Write a short piece (about 300 words) which links together the examples of gendered social interaction in public places with the idea that it is through such interactions that social structures are made and sustained. 68 Social Interaction and Everyday Life Activity 2: Shared understandings and the possibility of communication Read the section ‘The rules of social interaction’ from page 317 onwards. As the section shows, social life is only possible because of the shared cultural understandings which underpin our attempts at communication. All conversations are therefore placed within the culture in which they take place. Many conversations also depend on more specific instances of shared understanding or background knowledge such as the fairly detailed knowledge we all have about our friends and relatives or the shared knowledge about the operation of an institution which colleagues in a workplace share. Given below are a number of brief examples of conversational snippets in the form of a question followed by three possible answers to it. All of the answers could come from the same person in different social circumstances. Each example is followed by some questions about it to help you think about the ways in which shared understandings and knowledge underpin even the simplest of conversations. Example One Q: Why do you want this job? A1: I’m sick to death of having no money and although it’s not what I really want to do at the moment anything is better than nothing. A2: It’s got to the point where I think my Mum will throw me out if I don’t get a job and this is the only thing going at the moment. A3: I’m keen to get back to work and develop some real job skills alongside my qualifications. 1. Which of these answers is most appropriate for a job interview? 2. Which of these answers requires shared background knowledge of the individual’s domestic circumstances? 3. How do all of these answers rest on shared knowledge about the nature of the economy, employment and the current condition of the labour market? Example Two Q: How are you today? A1: Much better thanks. A2: The pain in my back seems to be fading now but my legs are still very sore. A3: Feeling really down. The pain’s getting better, but you know … 1. The appropriateness of these answers depends very much on the relationship between the questioner and the respondent. Which of the answers is most likely to be where the relationship is (a) doctor-patient; (b) close friends; (c) workplace colleagues. 2. All of the responses assume a level of shared understanding about both the immediate circumstances of the respondent and more general culturally accepted responses to illness. What are they? Example Three Q: What do you think about the new policy on education? A1: I try not to think about it. A2: It looks like a vote winner. Social Interaction and Everyday Life A3: At first sight it looks as incoherent and paradoxical as most education policies in the last ten years. If you scratch just below the surface the twin forces of neo-liberalism and social authoritarianism seem to be having their now customary battle for policy dominance. 1. Which of the responses is an attempt at making a joke? 2. The question itself makes a major assumption about the respondent’s knowledge base. What is it? Why might the questioner make that assumption? 3. What kind of vote might the policy be related to? What do you need to know about the political system to make this connection? 4. The third answer seems the most unusual. In what kinds of circumstances might it be made? Activity 3: The presentation of self in everyday life As the discussion of Goffman’s work shows, the management of our body and the presentation of ourselves as competent social actors, who are no threat to anyone, are omnipresent in our front region activities. For most of the time individuals are unaware of the extent of self-management and image maintenance they are engaged in: this is a marker not of the unimportance of the normal and everyday, but of its total importance in the smooth running of social life. In this exercise you will be looking at two examples of self-presentation, one where the elements of role-taking are most keenly felt and most consciously acted upon and one where they are more taken for granted. Select one activity from each category below: Special performances: the job interview the first date the court appearance Everyday performances: supermarket shopping going to work or college going to the cinema Write a short piece using the concepts of social role, encounter, focused interaction, unfocused interaction, front region, back region, impression management, personal space and social distance to describe and contrast the preparation and execution of these performances. REFLECTION & DISCUSSION QUESTIONS The micro and the macro Who are your neighbours? What kinds of interaction do you have with them? Are there places you feel uncomfortable visiting because of your gender? Are there social situations where you are not sure how to behave? Could an industrial society operate if nobody knew the time? Shared understandings and the possibility of communication Why is Shakespeare initially difficult to read? 70 Social Interaction and Everyday Life How is it possible to follow the plot of an opera sung in Italian? Do you ever have conversations that would be unintelligible to your parents? Do you ever have conversations with family members that would be unintelligible to people outside of your family? The presentation of the self in everyday life How does the idea of front and back regions help us to understand what is going on in a lecture, lesson or tutorial? How do you ‘look confident’? How do you act when you arrive late for an appointment? ESSAY QUESTIONS 1. In what ways can the dramaturgical model illuminate our understanding of two contrasting social encounters? 2. How has ethnomethodology contributed to the sociological understanding of human communication? 3. ‘It is impossible to overlook the fact that all human interactions take place in both time and space.’ Discuss the implications for sociology of this view. 4. In what ways are small-scale social interactions shaped by and in turn shape the larger structures of the society in which they take place? MAKING CONNECTIONS The micro and the macro: The relationship between these two scales of sociology provides an opportunity to link ‘theory’ and ‘methodology’ by using Chapter 1 on ‘Levels of analysis: microsociology and macrosociology’ and Chapter 2 on ethnography and ethical considerations in research. From Chapter 10 the work of Beck and Beck-Gernsheim could also be used as an illustration of the impact of macro forces on everyday life. There are also clear links to the issues of gender from Chapter 15. Shared understandings and the possibility of communication: This topic is primarily about face-to-face communication but could be broadened out to consider the use of mediated interaction and the possibility of communication within a global context – these issues are further discussed in Chapter 18 on the media. The presentation of the self in everyday life This links particularly well to discussions in Chapter 11 of the medical gaze, the sick role and biographical work. Social Interaction and Everyday Life SAMPLE SESSION The presentation of the self in everyday life Aims: To explore the notion of the presentation of the self and explore important concepts used within the dramaturgical model of social interaction. Outcome: By the end of the session students will be able to: Provide examples, drawn from their experience of completing the exercise, of social role, encounter, focused interaction, unfocused interaction, front region, back region, impression management, personal space and social distance. Preparatory task Read the sections ‘Face, body and speech in interaction’ and ‘The rules of social interaction’. Make notes which define and provide examples for the terms social role, encounter, focused interaction, unfocused interaction, front region, back region, impression management, personal space and social distance. Classroom tasks 1. Tutor to introduce the activity making explicit the links to the preparatory task. Split the class into six small groups, allocating each group one ‘performance’ from those listed in Activity 3, to discuss and make notes towards writing the short piece. (15–20 minutes) 2. Link the smaller groups together into three groups each of which comprises one group which has worked on a ‘Special performance’ and one which has worked on an ‘Everyday performance’. Give the new groups time to compare and contrast the examples. (20 minutes) 3. Tutor-led feedback from groups reinforcing the correct uses of the terms. (15 minutes) Assessment tasks Write the short piece specified in the Activity using the two examples discussed in their group. 72