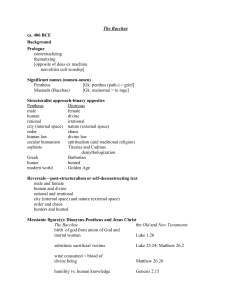

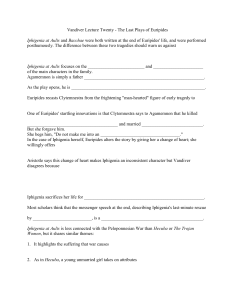

“HEALING STEPS”: JESUS' DIONYSIAC TOUR IN LUKE By

advertisement