Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: From sleepdisordered breathing

advertisement

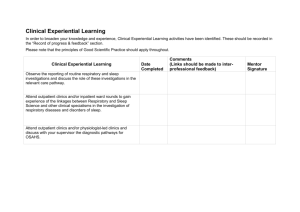

bs_bs_banner INVITED REVIEW SERIES: OBESITY AND RESPIRATORY DISORDERS SERIES EDITOR: AMANDA J PIPER Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: From sleep-disordered breathing to systemic comorbidities and the need to offer combined treatment strategies resp_2106 601..610 JEAN-CHRISTIAN BOREL,1,2 ANNE-LAURE BOREL,2,4 DENIS MONNERET,2 RENAUD TAMISIER,2,3 PATRICK LEVY2,3 AND JEAN-LOUIS PEPIN2,3 1 Research and Development Department ‘AGIR à dom’, Meylan, 2HP2 Laboratory, INSERM U 1042, Faculty of Medicine, Joseph Fourier University, 3Rehabilitation and Physiology Unit, and 4‘DIGIDUNE’ Unit, Endocrinology Department, University Hospital A. Michallon, Grenoble, France ABSTRACT Obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) is defined as a combination of obesity (body mass index ⱖ 30 kg/m2), daytime hypercapnia (partial arterial carbon dioxide concentration ⱖ45 mm Hg) and sleepdisordered breathing after ruling out other disorders that may cause alveolar hypoventilation. Through the prism of the International Classification of Functioning, OHS is a chronic condition associated with respiratory, metabolic, hormonal and cardiovascular impairments, leading to a decrease in daily life activi- ties, a lack of social participation and high risk of hospitalization and death. Despite its severity, OHS is largely underdiagnosed and the health-related costs are higher than those of apnoeic or obese eucapnic patients. The present review discusses the definition, epidemiology, physiopathology and treatment modalities of OHS. Although nocturnal positive airway pressure therapies represent first-line treatment and are effective in improving patient outcomes, there is a need to offer combined treatment strategies and to assess the effect of multimodal therapeutic strategies on morbidity and mortality. The Authors: Jean-Christian Borel, PhD, is the Head of the Research and Development Department at ‘AGIR à dom’, a non-profit home care provider. He has developed an expertise in the field of non-invasive ventilation, home-based training programmes and integrated care. He carried out his PhD thesis at the Hypoxia Pathophysiology Laboratory (HP2) on the clinical and cardiovascular consequences of the obesity hypoventilation syndrome, followed by a postdoctoral fellowship on the pathophysiology of the sleep apnoea syndrome in Dr Frederic Series’ team at the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute. Anne-Laure Borel, MD, PhD from Grenoble University Hospital, France, has completed a postdoctoral fellowship in Quebec, Canada in Dr Jean-Pierre Despres’ team of the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute. She is an endocrinologist with a clinical activity focused on obesity and type 2 diabetes. Her research interests are in the field of the cardiometabolic complications of an excess visceral adiposity and more specifically, the association between sleep-disordered breathing, excess visceral fat and metabolic abnormalities. Denis Monneret, MSc, PhD, is a pharmacist with a diploma of medical biology from Lille Faculty of Pharmacy, France. His MSc and PhD degrees specialized in biology of obstructive sleep apnoea and obesity hypoventilation syndrome. After working as Assistant Professor in the Biochemistry and Hormonology Unit at Grenoble University Hospital, he joined the HP2 Laboratory where he works on oxidative stress and metabolic biomarkers of obstructive sleep apnoea, and obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Renaud Tamisier, MD, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Physiology at Grenoble University School of Medicine, France. He works in the HP2 Laboratory and has been involved in both research and clinical studies in sleep-disordered breathing for the last 15 years. His research interests are mainly on the cardiovascular consequences of intermittent hypoxia and obstructive sleep apnoea. In the last 15 years, he has published over 40 papers in the best international journals of the respiratory and sleep fields. Jean-Louis Pépin, MD, PhD is Professor of Clinical Physiology and Head of the Clinical Physiology, Sleep and Exercise Department at Grenoble University Hospital. He is the President of the French Sleep Research Society. His clinical and research interests are mainly on the cardiovascular consequences associated with chronic and intermittent hypoxia, chronic respiratory failure and non-invasive ventilation. Patrick Lévy MD, PhD is Professor of Physiology at Grenoble University, France. He is the Head of the HP2 Laboratory (Inserm Unit 1042) and is the Clinical Vice-President of the European Sleep Research Society. He has been involved in sleep-disordered breathing for the last 25 years, and his clinical and research interests are mainly on obstructive sleep apnoea. He leads one of the most active research teams on obstructive sleep apnoea and intermittent hypoxia, which published over 200 manuscripts in the best international journals of the respiratory, cardiovascular and sleep fields. Correspondence: Jean-Christian Borel, AGIR à dom, Département Recherche et Développement, 29-31 Bd Des Alpes, 38244Meylan Cedex, France. Email: j.borel@agiradom.com Received 13 October 2011; invited to revise 17 October 2011; revised 20 October 2011; accepted 22 October 2011. © 2011 The Authors Respirology © 2011 Asian Pacific Society of Respirology Respirology (2012) 17, 601–610 doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02106.x 602 Key words: cardiovascular diseases, exercise and pulmonary rehabilitation, respiratory structure and function, sleep disorder. INTRODUCTION Although obesity, defined by a body mass index (BMI) ⱖ30 kg/m2, is associated with an increased rate of death from cardiovascular diseases and certain cancers,1 the mechanisms involved in these relationships are incompletely understood. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome is commonly associated with obesity2 and is a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity.3 Beyond obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome, a particular subgroup of obese patients is affected by chronic respiratory failure, the so-called obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS). These patients are characterized by a greater morbi-mortality than obese apnoeic patients, although this condition is often underdiagnosed. The present work reports definition, epidemiology, physiopathology and treatment modalities of OHS. DEFINITION OHS is defined as a combination of obesity (BMI ⱖ 30 kg/m2), daytime hypercapnia (partial arterial carbon dioxide concentration ⱖ45 mm Hg) and various types of sleep-disordered breathing after ruling out other disorders that may cause alveolar hypoventilation (severe obstructive or restrictive pulmonary diseases, chest wall disorders, neuromuscular diseases, severe hypothyroidism, and congenital central hypoventilation syndrome).4 Seventy to 90% of patients with OHS also exhibit obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome,5,6 while 10–15% of sleep apnoea patients referred through sleep laboratories have diurnal hypercapnia and can be classified as OHS.7 EPIDEMIOLOGY Although the overall prevalence of OHS has never been directly assessed in the general population, it is currently estimated at 3.7/1000 persons in the US population, which is one of the most overweight in the world.8 OHS prevalence has been more frequently assessed in patients referred to sleep clinics with a potential diagnosis of sleep-disordered breathing,6,9 in patients already diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA),7,10–13 as well as in a cohort of obese hospitalized patients.14 The prevalence is estimated between 10% and 20% in patients referred to sleep laboratories and rises to 20–30% or more in patients already diagnosed with OSA, as well as in hospitalized obese adult patients. There is a dose–response relationship between obesity as expressed by BMI and OHS prevalence.6,7,14 The different estimates of prevalence observed in these studies could be partly explained by the inclusion of patients with concomitant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease12 or patients with unstable medical status.14 Over the past decade, the progression of obesity seems to have staRespirology (2012) 17, 601–610 J-C Borel et al. bilized in the United States.15 However, extreme obesity among adults is still increasing.16,17 Thus, it could be anticipated that both prevalence and incidence of OHS will rise in the near future, and we can anticipate OHS to be a considerable health burden. GENERAL HEALTH STATUS, SOCIOECONOMICAL CONSEQUENCES AND MORTALITY OF OHS Among OHS patients admitted to hospital, only 20% had previously received the diagnosis of OHS.14 A large proportion of patients are diagnosed with OHS only when presenting with acute respiratory failure.11,18–20 This highlights that OHS is underdiagnosed or that the diagnosis is dramatically delayed. Yet, OHS patients are more likely to suffer from congestive heart failure,9 pulmonary hypertension5 and diabetes mellitus9,21 than obese eucapnic OSA patients. Moreover, the number of hospitalizations in the past few years,22 as well as the number of admissions in intensive care unit,14 are higher in newly diagnosed OHS patients than in eucapnic obese patients. As a consequence, the direct health costs (i.e. general practice services, hospital services, medications) per year of an OHS patient can reach twice that of an apnoeic patient23 or an obese eucapnic patient,22 and about six times that of an age, gender and socioeconomic status-matched control subject.23 Furthermore, labour income and employment rate are lower in OHS patients than in apnoeic patients or control subjects.23 The lack of social participation in OHS patients reflected by high unemployment rates is also in line with a poor social functioning score reported through questionnaire SF-36.24 OHS patients experience excessive daytime sleepiness9,24,25 that could be related to the severity of nocturnal rapid eye movement (REM) sleep hypoventilation (i.e. the higher the percentage of REM sleep spent in hypoventilation, the higher the excessive daytime sleepiness).25 Beyond the additional burden of comorbidities compared with eucapnic obese individuals, OHS patients have a higher risk of death, particularly when they are left untreated.14,19 In the study of Nowbar et al.,14 the mortality rate was 23%, 18 months after hospital discharge, compared with 9% in eupnoeic obese patients. OHS patients had a significantly higher hazard ratio for mortality (hazard ratio = 4.0) after adjustment for age, gender, BMI, electrolyte abnormalities, renal insufficiency, history of thromboembolism and history of hypothyroidism. In observational cohorts, mortality rate was reduced when OHS patients were treated with non-invasive ventilation (NIV),18,26–28 but it may remain higher than longterm mortality rates observed in large cohorts of obese patients.29 PATHOPHYSIOLOGY Because most OHS patients in a stable state are diagnosed when they present to sleep clinics, most © 2011 The Authors Respirology © 2011 Asian Pacific Society of Respirology 603 Obesity hypoventilation syndrome OBESITY HYPOVENTILATION SYNDROME Hormonal and Metabolic Leptin resistance Somatotropic axis impairment Insulin resistance Adiponectin Impairments Cardiovascular Endothelial dysfunction High prevalence of cardiovascular diseases Figure 1 Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: a chronic condition observed through the prism of the International Classification of Functioning. CRP, C-reactive protein; RANTES, regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted. Low Grade Inflammation hs-CRP RANTES Disabilities Exercise intolerance Respiratory Sleep breathing disorders Pulmonary volume restriction Respiratory muscle impairment Altered ventilatory drive Excessive daytime sleepiness Decrease in daily life activities Poor quality of life High unemployment rate High risk of hospitalization High risk of death studies looking for determinants of hypoventilation in obesity have consisted of cohorts of sleep apnoeic patients.7,9,10,13,30,31 In a recent meta-analysis, Kaw et al.31 have shown that daytime hypoventilation in obese sleep apnoeic patients was associated with severity of sleep apnoea, along with impaired chest wall mechanics and severity of obesity. These findings highlight that daytime hypoventilation in obese patients results from the conjunction of several factors that interact to overwhelm the compensatory mechanisms of CO2 homeostasis (Fig. 1).32,33 Respiratory mechanics A decrease in pulmonary volumes (vital capacity, total lung capacity, residual functional capacity) has been reported as a determinant of daytime hypercapnia in obese patients.6,7,12–14,30 This respiratory restriction, more pronounced in hypercapnic than in eucapnic obese patients,6,21,31,34,35 is associated with decreases in total respiratory system compliance and lung compliance;36 moreover, expiratory flow limitation in awake subjects can occur at low lung volume.37,38 Taken together, these alterations increase the work of breathing.34,39,40 Although mechanisms underlying this pulmonary restriction are incompletely understood, the decrease in lung volume is usually related to fat mass41 and to intrathoracic and abdominal fat distribution.41,42 These fat deposits could have direct mechanical effects on respiratory function by impeding diaphragm motion, changing the balance of elastic recoil between chest and lung. Another possible mechanism may be related to the metabolic syndrome and the low-grade inflammation associated with excess visceral and intrathoracic adiposity. Lin et al.43 have shown, in a large cohort study of more than 46 000 subjects without previously known respiratory © 2011 The Authors Respirology © 2011 Asian Pacific Society of Respirology Handicaps Lack of social participation High health-related costs disease, that metabolic syndrome was associated with a higher risk of restrictive lung impairment after adjustment for confounders (age, gender, BMI, physical activity, alcohol consumption). Additionally, other studies have reported an association between central adiposity and pulmonary restriction,41,44 and lower muscle strength in extra-respiratory muscles, as demonstrated by handgrip.45 Similarly, we have observed that OHS patients exhibit lower lung function, higher low-grade inflammation21 and higher waist/hip ratio (an anthropometric marker of central adiposity) than obese eucapnic patients. The lowgrade inflammation associated with metabolic syndrome and the higher work of breathing46 could induce specific muscle impairment in OHS leading to a deterioration in pulmonary function. Respiratory muscle function Although studies have shown that weight loss improves strength/endurance of respiratory muscles47,48 and sometimes hypoventilation,49 the question of inspiratory muscles weakness in OHS remains open. OHS patients are able to temporarily correct hypoventilation with voluntary breathing (i.e. hyperventilation).12 Additionally, during spontaneous breathing34 as well as during hypercapnic-induced hyperventilation,50 transdiaphragmatic pressure has been demonstrated higher or at least equivalent in OHS patients compared with obese eucapnic patients.34,50 Moreover, we recently observed that OHS patients exhibited somatotropic axis impairment compared with eucapnic obese patients. Insulin-like growth factor-I levels were inversely related to partial arterial carbon dioxide concentration levels and to vital capacity, which is an indirect marker of diaphragmatic strength.51 Taken together, these results suggest that muscle function is slightly impaired and Respirology (2012) 17, 601–610 604 does not allow compensation for the overload imposed on the respiratory system by OHS. The underlying causes for respiratory muscle dysfunction that may coexist in OHS include inflammation and somatotopic axis impairment. Further studies are needed to explore in detail respiratory muscle structure and function in OHS. Sleep-disordered breathing encountered in OHS patients Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome It is largely recognized that most OHS patients suffer from an obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome52 (Fig. 2) that could explain or at least contribute to daytime hypoventilation.31 The pathophysiology of sleep apnoea is multifactorial and has been discussed in detail by Isono53 in a previous paper in this series. In brief, upper airway closure occurs when pharyngeal dilating forces cannot overcome the collapsing effect J-C Borel et al. of the negative transmural inspiratory pressure gradient and the tissue weight.54 Excessive fat deposition induces an enlargement of soft tissue surrounding the upper airway, compromising the pharyngeal airspace55 and therefore predisposing the airway to closure during sleep.54 Moreover, the reduced lung volume, particularly present in OHS patients,31 reduces the inspiratory-related caudal tracheal traction56 that stabilizes upper airway structures.54 Beyond these anatomical predispositions to sleep apnoea, it has recently been proposed that fluid shifts from the legs to the neck during sleep (because of the recumbent position), contributing to the pathogenesis of sleep apnoea.57,58 Although this hypothesis remains debated,59 Redolfi et al. have shown that prevention in daytime fluid accumulation in the legs reduces apnoea/hypopnoea index.60,61 As OHS patients are likely to exhibit cor pulmonale22 and consequently fluid overload and peripheral oedema, their upper airway collapsibility might be increased by nocturnal rostral fluid shift. To test the importance of this phenomenon, the severity of sleep apnoea and Figure 2 (a) Polysomnographic pattern of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. ABD, abdominal movements; EOG, electro-occulogram; FLOW, nasal pressure; PTT, pulse transit time (an indirect measure of respiratory effort); SpO2, oxygen blood saturation; THERM, bucconasal thermistor; THO, thoracic movements. (b) schematic representation of insufficient post-event ventilatory compensation (adapted from reference 63 with authorization) contributing to the pathogenesis of diurnal hypoventilation via alteration of ventilatory drive (see text for further details). Respirology (2012) 17, 601–610 © 2011 The Authors Respirology © 2011 Asian Pacific Society of Respirology 605 Obesity hypoventilation syndrome Figure 3 Polysomnographic pattern of REM sleep hypoventilation. (a) 5-min epoch. A2-C3, electroencephalogram; ABD, abdominal movements; EOG, electro-occulogram; FLO, nasal pressure; SpO2, oxygen blood saturation; THER, bucconasal thermistor; THO, thoracic movements. (b) Overnight hypnogram: see the increase in PtCO2 during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. the ratio of central versus obstructive events from acute exacerbation to a chronic stable condition remain to be studied. The pattern of sleep apnoea is a key in the development of hypercapnia in OHS patients. The mean duration of apnoea and hypopnoea is increased with a reduced duration and amplitude of interapnoea ventilation.62 This insufficient post-event ventilatory compensation63 may contribute to the interaction between sleep apnoea syndrome and diurnal hypoventilation. Accordingly, the severity of sleep apnoea syndrome—appreciated by overnight apnoea/hypopnoea index—contributes to diurnal hypoventilation in obese apnoeic patients.31 Central hypoventilation Another type of sleep respiratory abnormality encountered in patients with OHS is central hypoventilation (Fig. 3) that is characterized by a sustained reduction in ventilation associated with a constant or reduced respiratory drive.25,64 Hypoventilation is more pronounced during REM sleep64 and the proportion of REM sleep hypoventilation is associated to awake ventilatory response to CO2. Indeed the lower awake © 2011 The Authors Respirology © 2011 Asian Pacific Society of Respirology CO2 ventilatory response, the higher the percentage of REM sleep spent in hypoventilation.25 There is increasing evidence that sleep-breathing disorders contribute to the pathogenesis of diurnal hypoventilation via alteration of ventilatory drive.65 Ventilatory drive Norman et al.65 have recently proposed a computational model that unifies acute hypercapnia during sleep-breathing events with chronic sustained hypoventilation during wakefulness. In this model, the persistence of elevated bicarbonate concentration after the sleep period (characterized by repetitive acute hypercapnia events), possibly due to either alteration of renal excretion or reduction in ventilatory drive (or both), further blunts ventilatory response to CO2, which in turn increases partial arterial carbon dioxide concentration. In a recent study, we observed that the improvement in bicarbonate concentration after 1 month of nocturnal NIV was related to NIV-induced nocturnal oxygen blood saturation improvement.66 This result supports the hypothesis of a link between nocturnal breathing disorders and daytime hypoventilation (Fig. 2b). Nevertheless, although diurnal Respirology (2012) 17, 601–610 606 partial arterial carbon dioxide concentration and bicarbonate concentration were improved after 1month NIV, the ventilatory response to CO2 remained unchanged, suggesting that other factors may play a role in respiratory drive impairment in OHS. The hypothesis of familial impairment of respiratory drive has been evoked, but Jokic et al. have shown that ventilatory chemoresponsiveness was similar between first-degree relatives of OHS patients compared with age- and BMI-matched control subjects.67 Another hypothesis, supported by animal studies, is the participation of neurohumoral agents such as adipokine leptin that acts as a powerful ventilatory stimulant.68,69 In humans, congenital leptin deficiency exists but is very rare;70 on the contrary, in obese subjects circulating leptin levels are often higher than those in lean subjects.71–75 These results suggest that a central resistance to leptin may occur in obesity. A possible mechanism for this central resistance could be deficient leptin transport through the blood–brain barrier.76,77 Inflammation, insulin resistance and somatotropic impairment in OHS Obesity is a disease state characterized by chronic systemic low-grade inflammation and associated inflammatory changes in the adipose tissue.78 Inflammatory status in OHS patients has not been extensively studied, but Budweiser et al. found that C-reactive protein, a systemic biomarker of inflammation, was associated with poor survival.26 We recently observed that moderate OHS patients had a higher level of highsensitivity C-reactive protein, a higher level of the proatherogenic chemokine regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted and a lower adiponectin level (an antiatherogenic and insulinsensitizing adipokine) compared with age- and BMImatched eucapnic control subjects.21 Accordingly, OHS patients exhibited higher insulin resistance, higher glycated Hb and were more likely to be treated by glucose-lowering medications. Endothelial dysfunction, an early key event of atherosclerosis and a strong predictor of incident cardiovascular events,79 was also more impaired in OHS patients compared with eucapnic obese patients.21 Additionally, the impairment in somatotropic axis, as demonstrated by low insulin-like growth factor-I level,51 may contribute to this endothelial dysfunction.80 Taken together, these results support a particular cardiovascular risk associated with OHS and confirm the results of observational cohorts data, demonstrating a higher prevalence of cardiovascular diseases.9,22,26 TREATMENT MODALITIES Through the prism of the International Classification of Functioning81 (Fig. 1), OHS is a chronic condition associated with impairments of body structures (upper airway, respiratory muscles) or body functions (control of breathing, sleep, cardiovascular, metabolic), decrease in activities and a lack of social participation. Thus, in the absence of guidelines on Respirology (2012) 17, 601–610 J-C Borel et al. treatment modalities being clearly established in OHS, clinicians should adapt treatment modalities aimed at improving specific impairments, dysfunctions and handicaps of each patient. From this perspective, the three main tools available for clinicians are positive airway pressure therapies (continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and/or NIV), body weight loss strategies and rehabilitation. Positive airway pressure therapies to abolish sleep-breathing disorders Positive airway pressure therapies (CPAP and/or NIV) represent the first-line therapy for sleep-breathing disorders. The choice of nocturnal CPAP or NIV is often based on the underlying sleep-related respiratory abnormality encountered.82 CPAP is efficient in reversing diurnal hypoventilation82–85 in OHS patients presenting mainly OSA-related hypoventilation. Piper et al.85 have shown that more than 60% of OHS patients who exhibited an incomplete initial response to CPAP have a good response after 3 months of CPAP, suggesting that incomplete immediate response to CPAP does not preclude midterm efficacy. However, some OHS patients continue to exhibit sleep hypoventilation,82,83,85,86 particularly in REM,25,35 even though upper airway obstruction is abolished with CPAP, and require NIV to overcome this central hypoventilation. In contrast to CPAP, NIV is more expensive and more complex to set up a large range of ventilatory parameters (ventilatory mode, inspiratory and expiratory pressures, back-up respiratory rate, triggering sensitivity, pressurization slope).87 Moreover, residual respiratory events occur frequently in OHS patients treated with nocturnal NIV. Additional attention is required to ensure treatment efficacy and avoid machine-related undesirable respiratory events.88,89 Thus, in the absence of long-term randomized trials comparing NIV with CPAP in patients with predominant OSA-related hypoventilation,85 NIV should be reserved for OHS patients presenting with primarily central hypoventilation during sleep. Manufacturers have proposed new ventilatory modes (example: average volume-assured pressure support, volume targeting by bi-level positive pressure ventilation90,91 and auto-titrating NIV92), but the efficacy of these modes needs to be assessed in larger cohort studies and on a long-term follow-up basis. Long-term uncontrolled studies have consistently reported a lower mortality rate in OHS patients treated with NIV26–28 compared with those in a cohort principally composed of untreated patients.14 Additionally, these studies have shown an improvement in gas exchange.26,28 Beyond hypoventilation, basal atelectasis or coexisting lung disease may lead to obesity-related hypoxia. Therefore, additional oxygen therapy may be necessary to correct persistent hypoxaemia even under efficient positive airway pressure therapy. Of note, the need for supplemental oxygen therapy and baseline hypoxaemia have been shown as independent predictors of mortality.26–28 In a recent randomized controlled trial including moderate OHS patient, partial arterial oxygen concentration © 2011 The Authors Respirology © 2011 Asian Pacific Society of Respirology 607 Obesity hypoventilation syndrome was not significantly improved after 1 month of nocturnal NIV.66 Even though baseline hypoxaemia was very mild, this result supports the concept that obesity-related hypoxaemia might be more difficult to correct than hypercapnia. Additionally, this randomized controlled trial failed to demonstrate that shortterm nocturnal NIV could impact favourably on metabolic, cardiovascular or inflammatory markers in spite of the improvements in pulmonary function and sleep parameters. This suggests that positive airway pressure therapies should not be the only form of treatment for these patients.66 Effect of body weight loss, changes in lifestyle habits and rehabilitation programmes Previous studies have largely documented the benefits of body weight loss to correct or attenuate sleep apnoea related to obesity. Indeed, Peppard et al.93 have studied a cohort of 690 subjects and demonstrated that 10% weight gain or weight loss were respectively associated with a 32% increase or a 26% decrease in the apnoea/hypopnoea index. Intervention studies designed to allow weight loss in obese patients have largely shown that weight loss achieved either by bariatric surgery (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, vertical-banded gastroplasty)94,95 or by lifestyle intervention96–99 was associated with an improvement in sleep-related breathing disorders. Body weight loss obviously seems to be the etiological treatment in OHS. The correction of OHS related to weight loss following bariatric surgery has been addressed in some studies that have reported an improvement in diurnal hypoventilation, as well as an improvement in spirometric parameters.49,100–102 Whereas bariatric surgery seems to be an interesting option for treatment of OHS, two points have to be considered: first, a multicentre study identified sleep apnoea syndrome as an independent factor associated with an increased risk of major adverse outcome during the 30 days following bariatric surgery in a large cohort of patients;103 and second, recurrent sleep-disordered breathing, as well as deterioration of blood gas and spirometric parameters,102 were observed in a follow-up of bariatric surgery patients, even though these patients did not regain weight.104 The level of physical activity is another characteristic of lifestyle habits that is associated with sleepdisordered breathing and may be corrected by lifestyle intervention programmes. Indeed, the level of physical activity is inversely correlated to the apnoea/hypopnoea index.93 In addition, an increase in physical activity is also associated with a decrease in visceral fat accumulation,105 and with an improvement in low-grade inflammation. Physical activity also improves metabolic profile and muscle function. Therefore, OHS patients may benefit from an increase in physical activity, as well as from weight loss, acting synergistically to improve the respiratory disturbances and comorbidities of OHS. Compared with obese eucapnic OSA patients, individuals with OHS exhibit a lower exercise tolerance.106 In contrast, in a study of patients with a range of dis© 2011 The Authors Respirology © 2011 Asian Pacific Society of Respirology orders causing chronic respiratory failure and treated with long-term NIV, Budweiser et al.107 have shown that OHS patients had a relatively preserved functional capacity (i.e. 6MWD test) compared with patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or thoracic restriction. Moreover, among these different causes of respiratory failure, exercise tolerance was improved after 2 months of nocturnal NIV.108 However, in OHS patients, in spite of correction of partial arterial carbon dioxide concentration after 3 months of NIV, these patients continued to exhibit exercise-induced hypoventilation.106 In a recent study aimed at comparing a low-calorie diet and a physical activity programme plus respiratory muscles training versus the same programme without respiratory muscle training, the former strategy induced greater improvement in dyspnoea and exercise capacity than the latter one.109 On the other hand, NIV during exercise training might also be an aid to enhance exercise capacity in rehabilitation programmes.110 Taken together, these results suggest that specific exercisebased rehabilitation programmes including NIV and respiratory muscle training are likely to benefit these patients, and the onset of NIV could be the appropriate time to start such programmes. Nevertheless, the best modalities to include in these programmes have to be determined in order to improve motivation,111 adherence and long-term benefits. CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVES Although largely underdiagnosed, OHS is characterized by sleep, respiratory, metabolic and cardiovascular impairments leading to a decrease in activities, a lack of social participation and a higher mortality rate. Although CPAP/NIV represent first-line therapy to treat sleep-related breathing disorders, they cannot be considered as the only therapeutic strategy. Weight loss strategies (surgical and non-surgical), as well as changes in lifestyle habits and rehabilitation programmes, should be proposed. Finally, long-term, large-scale multicentre studies are required to assess the effect of multimodal therapeutic strategies on morbidity and mortality. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The authors thank Suzanne Lamothe for language revision. REFERENCES 1 Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet 2009; 373: 1083–96. 2 Young T, Shahar E, Nieto FJ et al. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002; 162: 893–900. 3 Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M et al. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000; 342: 1378–84. 4 Mokhlesi B. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: a state-of-theart review. Respir. Care 2010; 55: 1347–62. discussion 63–5. Respirology (2012) 17, 601–610 608 5 Kessler R, Chaouat A, Schinkewitch P et al. The obesityhypoventilation syndrome revisited: a prospective study of 34 consecutive cases. Chest 2001; 120: 369–76. 6 Resta O, Foschino-Barbaro MP, Bonfitto P et al. Prevalence and mechanisms of diurnal hypercapnia in a sample of morbidly obese subjects with obstructive sleep apnoea. Respir. Med. 2000; 94: 240–6. 7 Laaban JP, Chailleux E. Daytime hypercapnia in adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in France, before initiating nocturnal nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Chest 2005; 127: 710–15. 8 Mokhlesi B, Saager L, Kaw R. Q: Should we routinely screen for hypercapnia in sleep apnea patients before elective noncardiac surgery? Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2010; 77: 60–1. 9 Trakada GP, Steiropoulos P, Nena E et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of obesity hypoventilation syndrome among individuals reporting sleep-related breathing symptoms in Northern Greece. Sleep Breath. 2010; 14: 381–6. 10 Akashiba T, Kawahara S, Kosaka N et al. Determinants of chronic hypercapnia in Japanese men with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest 2002; 121: 415–21. 11 Golpe R, Jimenez A, Carpizo R. Diurnal hypercapnia in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest 2002; 122: 1100–1. 12 Leech JA, Onal E, Baer P et al. Determinants of hypercapnia in occlusive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest 1987; 92: 807–13. 13 Mokhlesi B, Tulaimat A, Faibussowitsch I et al. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: prevalence and predictors in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2007; 11: 117–24. 14 Nowbar S, Burkart KM, Gonzales R et al. Obesity-associated hypoventilation in hospitalized patients: prevalence, effects, and outcome. Am. J. Med. 2004; 116: 1–7. 15 Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA 2010; 303: 235– 41. 16 Sturm R. Increases in morbid obesity in the USA: 2000–2005. Public Health 2007; 121: 492–6. 17 Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Obesity prevalence in the United States—up, down, or sideways? N. Engl. J. Med. 2011; 364: 987–9. 18 Laub M, Midgren B. Survival of patients on home mechanical ventilation: a nationwide prospective study. Respir. Med. 2007; 101: 1074–8. 19 Perez de Llano LA, Golpe R, Ortiz Piquer M et al. Short-term and long-term effects of nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation in patients with obesity-hypoventilation syndrome. Chest 2005; 128: 587–94. 20 Quint JK, Ward L, Davison AG. Previously undiagnosed obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Thorax 2007; 62: 462–3. 21 Borel JC, Roux-Lombard P, Tamisier R et al. Endothelial dysfunction and specific inflammation in obesity hypoventilation syndrome. PLoS ONE 2009; 4: e6733. 22 Berg G, Delaive K, Manfreda J et al. The use of health-care resources in obesity-hypoventilation syndrome. Chest 2001; 120: 377–83. 23 Jennum P, Kjellberg J. Health, social and economical consequences of sleep-disordered breathing: a controlled national study. Thorax 2011; 66: 560–6. 24 Hida W, Okabe S, Tatsumi K et al. Nasal continuous positive airway pressure improves quality of life in obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Sleep Breath. 2003; 7: 3–12. 25 Chouri-Pontarollo N, Borel JC, Tamisier R et al. Impaired objective daytime vigilance in obesity-hypoventilation syndrome: impact of noninvasive ventilation. Chest 2007; 131: 148–55. 26 Budweiser S, Riedl SG, Jorres RA et al. Mortality and prognostic factors in patients with obesity-hypoventilation syndrome undergoing noninvasive ventilation. J. Intern. Med. 2007; 261: 375–83. 27 Heinemann F, Budweiser S, Dobroschke J et al. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation improves lung volumes in the obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Respir. Med. 2007; 101: 1229–35. Respirology (2012) 17, 601–610 J-C Borel et al. 28 Priou P, Hamel JF, Person C et al. Long-term outcome of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation for obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Chest 2010; 138: 84–90. 29 Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007; 357: 753–61. 30 Akashiba T, Akahoshi T, Kawahara S et al. Clinical characteristics of obesity-hypoventilation syndrome in Japan: a multicenter study. Intern. Med. 2006; 45: 1121–5. 31 Kaw R, Hernandez AV, Walker E et al. Determinants of hypercapnia in obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and metaanalysis of cohort studies. Chest 2009; 136: 787–96. 32 BaHammam A. Is apnea hypopnea index a good predictor for obesity hypoventilation syndrome in patients with obstructive sleep apnea? Sleep Breath. 2007; 11: 201. author reply 3–4. 33 Gozal D. Determinants of daytime hypercapnia in obstructive sleep apnea: is obesity the only one to blame? Chest 2002; 121: 320–1. 34 Pankow W, Hijjeh N, Schuttler F et al. Influence of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation on inspiratory muscle activity in obese subjects. Eur. Respir. J. 1997; 10: 2847–52. 35 Piper AJ, Grunstein RR. Big Breathing—the complex interaction of obesity, hypoventilation, weight loss and respiratory function. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009; 108: 199–205. 36 Behazin N, Jones SB, Cohen RI et al. Respiratory restriction and elevated pleural and esophageal pressures in morbid obesity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010; 108: 212–8. 37 Pankow W, Podszus T, Gutheil T et al. Expiratory flow limitation and intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure in obesity. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998; 85: 1236–43. 38 Salome CM, King GG, Berend N. Physiology of obesity and effects on lung function. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010; 108: 206– 11. 39 Lee MY, Lin CC, Shen SY et al. Work of breathing in eucapnic and hypercapnic sleep apnea syndrome. Respiration 2009; 77: 146–53. 40 Lin CC, Wu KM, Chou CS et al. Oral airway resistance during wakefulness in eucapnic and hypercapnic sleep apnea syndrome. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2004; 139: 215–24. 41 Lazarus R, Sparrow D, Weiss ST. Effects of obesity and fat distribution on ventilatory function: the normative aging study. Chest 1997; 111: 891–8. 42 Babb TG, Wyrick BL, DeLorey DS et al. Fat distribution and end-expiratory lung volume in lean and obese men and women. Chest 2008; 134: 704–11. 43 Lin WY, Yao CA, Wang HC et al. Impaired lung function is associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome in adults. Obesity 2006; 14: 1654–61. 44 Collins LC, Hoberty PD, Walker JF et al. The effect of body fat distribution on pulmonary function tests. Chest 1995; 107: 1298–302. 45 Lazarus R, Gore CJ, Booth M et al. Effects of body composition and fat distribution on ventilatory function in adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998; 68: 35–41. 46 Vassilakopoulos T, Hussain SN. Ventilatory muscle activation and inflammation: cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and nitric oxide. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007; 102: 1687–95. 47 Kelly TM, Jensen RL, Elliott CG et al. Maximum respiratory pressures in morbidly obese subjects. Respiration 1988; 54: 73–7. 48 Weiner P, Waizman J, Weiner M et al. Influence of excessive weight loss after gastroplasty for morbid obesity on respiratory muscle performance. Thorax 1998; 53: 39–42. 49 Marti-Valeri C, Sabate A, Masdevall C et al. Improvement of associated respiratory problems in morbidly obese patients after open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes. Surg. 2007; 17: 1102– 10. 50 Sampson MG, Grassino K. Neuromechanical properties in obese patients during carbon dioxide rebreathing. Am. J. Med. 1983; 75: 81–90. © 2011 The Authors Respirology © 2011 Asian Pacific Society of Respirology Obesity hypoventilation syndrome 51 Monneret D, Borel JC, Pepin JL et al. Pleiotropic role of IGF-I in obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2010; 20: 127–33. 52 Rapoport DM. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: more than just severe sleep apnea. Sleep Med. Rev. 2011; 15: 77–8. 53 Isono S. Obesity and obstructive sleep apnoea: mechanisms for increased collapsibility of the passive pharyngeal airway. Respirology 2011; ‘Accepted Article’; doi: 10.1111/J.14401843.2011.02093.x. 54 Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ et al. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol. Rev. 2010; 90: 47–112. 55 Schwab RJ, Gupta KB, Gefter WB et al. Upper airway and soft tissue anatomy in normal subjects and patients with sleepdisordered breathing. Significance of the lateral pharyngeal walls. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995; 152: 1673–89. 56 Thut DC, Schwartz AR, Roach D et al. Tracheal and neck position influence upper airway airflow dynamics by altering airway length. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993; 75: 2084–90. 57 Redolfi S, Yumino D, Ruttanaumpawan P et al. Relationship between overnight rostral fluid shift and obstructive sleep apnea in nonobese men. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009; 179: 241–6. 58 Yumino D, Redolfi S, Ruttanaumpawan P et al. Nocturnal rostral fluid shift: a unifying concept for the pathogenesis of obstructive and central sleep apnea in men with heart failure. Circulation 2010; 121: 1598–605. 59 Jafari B, Mohsenin V. Overnight rostral fluid shift in obstructive sleep apnea: Does it affect the severity of sleep-disordered breathing? Chest 2011; 140: 991–7. 60 Redolfi S, Arnulf I, Pottier M et al. Effects of venous compression of the legs on overnight rostral fluid shift and obstructive sleep apnea. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2011; 175: 390–3. 61 Redolfi S, Arnulf I, Pottier M et al. Attenuation of obstructive sleep apnea by compression stockings in subjects with venous insufficiency. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011; PMID 21836140 [Epub ahead of print]. 62 Ayappa I, Berger KI, Norman RG et al. Hypercapnia and ventilatory periodicity in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002; 166: 1112–5. 63 Berger KI, Ayappa I, Sorkin IB et al. Postevent ventilation as a function of CO(2) load during respiratory events in obstructive sleep apnea. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002; 93: 917–24. 64 Becker HF, Piper AJ, Flynn WE et al. Breathing during sleep in patients with nocturnal desaturation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999; 159: 112–8. 65 Norman RG, Goldring RM, Clain JM et al. Transition from acute to chronic hypercapnia in patients with periodic breathing: predictions from a computer model. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006; 100: 1733–41. 66 Borel JC, Tamisier R, Gonzalez-Bermejo J et al. Noninvasive ventilation in mild obesity hypoventilation syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2011; PMID: 21885724 [Epub ahead of print]. 67 Jokic R, Zintel T, Sridhar G et al. Ventilatory responses to hypercapnia and hypoxia in relatives of patients with the obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Thorax 2000; 55: 940–5. 68 O’Donnell CP, Schaub CD, Haines AS et al. Leptin prevents respiratory depression in obesity. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999; 159: 1477–84. 69 O’Donnell CP, Tankersley CG, Polotsky VP et al. Leptin, obesity, and respiratory function. Respir. Physiol. 2000; 119: 163–70. 70 Montague CT, Farooqi IS, Whitehead JP et al. Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature 1997; 387: 903–8. 71 Dagogo-Jack S, Fanelli C, Paramore D et al. Plasma leptin and insulin relationships in obese and nonobese humans. Diabetes 1996; 45: 695–8. 72 Maffei M, Halaas J, Ravussin E et al. Leptin levels in human and rodent: measurement of plasma leptin and ob RNA in obese and weight-reduced subjects. Nat. Med. 1995; 1: 1155–61. © 2011 The Authors Respirology © 2011 Asian Pacific Society of Respirology 609 73 Campo A, Fruhbeck G, Zulueta JJ et al. Hyperleptinaemia, respiratory drive and hypercapnic response in obese patients. Eur. Respir. J. 2007; 30: 223–31. 74 Phipps PR, Starritt E, Caterson I et al. Association of serum leptin with hypoventilation in human obesity. Thorax 2002; 57: 75–6. 75 Shimura R, Tatsumi K, Nakamura A et al. Fat accumulation, leptin, and hypercapnia in obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Chest 2005; 127: 543–9. 76 Caro JF, Kolaczynski JW, Nyce MR et al. Decreased cerebrospinal-fluid/serum leptin ratio in obesity: a possible mechanism for leptin resistance. Lancet 1996; 348: 159– 61. 77 Schwartz MW, Peskind E, Raskind M et al. Cerebrospinal fluid leptin levels: relationship to plasma levels and to adiposity in humans. Nat. Med. 1996; 2: 589–93. 78 Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006; 444: 860–7. 79 Deanfield JE, Halcox JP, Rabelink TJ. Endothelial function and dysfunction: testing and clinical relevance. Circulation 2007; 115: 1285–95. 80 Conti E, Carrozza C, Capoluongo E et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 as a vascular protective factor. Circulation 2004; 110: 2260–5. 81 World Health Organisation. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). [Accessed 15 Sep 2011.] Available from URL: http://www.who.int/classifications/ icf/en/ 82 Berger KI, Ayappa I, Chatr-Amontri B et al. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome as a spectrum of respiratory disturbances during sleep. Chest 2001; 120: 1231–8. 83 Mokhlesi B, Tulaimat A, Evans AT et al. Impact of adherence with positive airway pressure therapy on hypercapnia in obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2006; 2: 57–62. 84 Perez de Llano LA, Golpe R, Piquer MO et al. Clinical heterogeneity among patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome: therapeutic implications. Respiration 2008; 75: 34–9. 85 Piper AJ, Wang D, Yee BJ et al. Randomised trial of CPAP vs bilevel support in the treatment of obesity hypoventilation syndrome without severe nocturnal desaturation. Thorax 2008; 63: 395–401. 86 Banerjee D, Yee BJ, Piper AJ et al. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: hypoxemia during continuous positive airway pressure. Chest 2007; 131: 1678–84. 87 Rabec C, Rodenstein D, Leger P et al. Ventilator modes and settings during non-invasive ventilation: effects on respiratory events and implications for their identification. Thorax 2011; 66: 170–8. 88 Gonzalez-Bermejo J, Perrin C, Janssens JP et al. Proposal for a systematic analysis of polygraphy or polysomnography for identifying and scoring abnormal events occurring during noninvasive ventilation. Thorax 2010; PMID: 20971982 [Epub ahead of print]. 89 Janssens J, Pépin J, Guo Y. Non invasive ventilation and chronic respiratory failure secondary to obesity. Eur. Respir. Mon. 2008; 41: 251–64. 90 Janssens JP, Metzger M, Sforza E. Impact of volume targeting on efficacy of bi-level non-invasive ventilation and sleep in obesity-hypoventilation. Respir. Med. 2009; 103: 165–72. 91 Storre JH, Seuthe B, Fiechter R et al. Average volume-assured pressure support in obesity hypoventilation: a randomized crossover trial. Chest 2006; 130: 815–21. 92 Jaye J, Chatwin M, Dayer M et al. Autotitrating versus standard noninvasive ventilation: a randomised crossover trial. Eur. Respir. J. 2009; 33: 566–71. 93 Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M et al. Longitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep-disordered breathing. JAMA 2000; 284: 3015–21. 94 Fritscher LG, Canani S, Mottin CC et al. Bariatric surgery in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in morbidly obese patients. Respiration 2007; 74: 647–52. Respirology (2012) 17, 601–610 610 95 Valencia-Flores M, Orea A, Herrera M et al. Effect of bariatric surgery on obstructive sleep apnea and hypopnea syndrome, electrocardiogram, and pulmonary arterial pressure. Obes. Surg. 2004; 14: 755–62. 96 Foster GD, Borradaile KE, Sanders MH et al. A randomized study on the effect of weight loss on obstructive sleep apnea among obese patients with type 2 diabetes: the Sleep AHEAD study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009; 169: 1619–26. 97 Johansson K, Neovius M, Lagerros YT et al. Effect of a very low energy diet on moderate and severe obstructive sleep apnoea in obese men: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009; 339: b4609. 98 Tuomilehto H, Gylling H, Peltonen M et al. Sustained improvement in mild obstructive sleep apnea after a diet- and physical activity-based lifestyle intervention: postinterventional followup. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010; 92: 688–96. 99 Tuomilehto HP, Seppa JM, Partinen MM et al. Lifestyle intervention with weight reduction: first-line treatment in mild obstructive sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009; 179: 320–7. 100 Boone KA, Cullen JJ, Mason EE et al. Impact of Vertical Banded Gastroplasty on Respiratory Insufficiency of Severe Obesity. Obes. Surg. 1996; 6: 454–8. 101 Lumachi F, Marzano B, Fanti G et al. Hypoxemia and hypoventilation syndrome improvement after laparoscopic bariatric surgery in patients with morbid obesity. InVivo 2010; 24: 329–31. 102 Sugerman HJ, Fairman RP, Sood RK et al. Long-term effects of gastric surgery for treating respiratory insufficiency of obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1992; 55: 597S–601S. 103 Flum DR, Belle SH, King WC et al. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009; 361: 445–54. Respirology (2012) 17, 601–610 J-C Borel et al. 104 Pillar G, Peled R, Lavie P. Recurrence of sleep apnea without concomitant weight increase 7.5 years after weight reduction surgery. Chest 1994; 106: 1702–4. 105 Ross R, Dagnone D, Jones PJ et al. Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after diet-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000; 133: 92–103. 106 Schonhofer B, Rosenbluh J, Voshaar T et al. [Ergometry separates sleep apnea syndrome from obesity-hypoventilation after therapy positive pressure ventilation therapy]. Pneumologie 1997; 51: 1115–9. 107 Budweiser S, Heidtkamp F, Jorres RA et al. Predictive significance of the six-minute walk distance for long-term survival in chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure. Respiration 2008; 75: 418–26. 108 Schonhofer B, Zimmermann C, Abramek P et al. Non-invasive mechanical ventilation improves walking distance but not quadriceps strength in chronic respiratory failure. Respir. Med. 2003; 97: 818–24. 109 Villiot-Danger JC, Villiot-Danger E, Borel JC et al. Respiratory muscle endurance training in obese patients. Int. J. Obes. 2011; 35: 692–9. 110 Dreher M, Kabitz HJ, Burgardt V et al. Proportional assist ventilation improves exercise capacity in patients with obesity. Respiration 2010; 80: 106–11. 111 Jordan KE, Ali M, Shneerson JM. Attitudes of patients towards a hospital-based rehabilitation service for obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Thorax 2009; 64: 1007. © 2011 The Authors Respirology © 2011 Asian Pacific Society of Respirology