chapter 9 - University of Toronto

advertisement

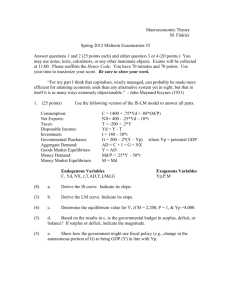

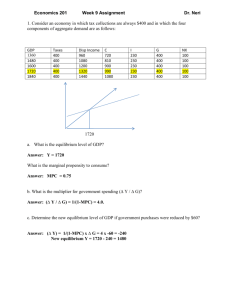

Prof. Gustavo Indart Department of Economics University of Toronto ECO209 MACROECONOMIC THEORY Chapter 11 MONEY, INTEREST, AND INCOME Discussion Questions: 1. The model in Chapter 9 assumed that both the price level and the interest rate were fixed. But the IS-LM model lets the interest rate fluctuate and determines the combination of output demanded and the interest rate for a fixed price level. It should be noted that while the upward-sloping AD-curve in Chapter 9 (the [C+I+G+NX]-line in the Keynesian cross diagram) assumed that interest rates and prices were fixed, the downward-sloping AD-curve that is derived at the end of Chapter 10 from the IS-LM model lets the price level fluctuate and describes all combinations of the price level and the level of output demanded at which the goods and money sector simultaneously are in equilibrium. 2.a. If the expenditure multiplier (α) becomes larger, the increase in equilibrium income caused by a unit change in intended spending also becomes larger. Assume investment spending increases due to a change in the interest rate. If the multiplier α becomes larger, any increase in spending will cause a larger increase in equilibrium income. This means that the IS-curve will become flatter as the size of the expenditure multiplier becomes larger. If aggregate demand becomes more sensitive to interest rates, any change in the interest rate causes the [C+I+G+NX]-line to shift up by a larger amount and, given a certain size of the expenditure multiplier α, this will increase equilibrium income by a larger amount. As a result, the IS-curve will become flatter. 2.b. Monetary policy changes affect interest rates and this leads to a change in intended spending, which is reflected in a change in income. In 2.a. it was explained that a steep IScurve means either that the multiplier α is small or that desired spending is not very interest sensitive. Therefore, an increase in money supply will reduce interest rates. However, this does not result in a large increase in aggregate demand if spending is very interest insensitive. Similarly, if the multiplier is small, then any change in spending will not affect output significantly. Therefore, the steeper the IS-curve, the weaker the effect of monetary policy changes on equilibrium output. 2 3. Assume that money supply is fixed. Any increase in income will increase money demand and the resulting excess demand for money will drive the interest rate up. This, in turn, will reduce the quantity of money balances demanded to bring the money sector back to equilibrium. But if money demand is very interest insensitive, then a larger increase in the interest rate is needed to reach a new equilibrium in the money sector. As a result, the LMcurve becomes steeper. Along the LM-curve, an increase in the interest rate is always associated with an increase in income. This means that an increase in money demand (due to an increase in income) has to be offset by a decrease in the quantity of money demanded (due to an increase in the interest rate) to keep the money sector in equilibrium. But if money demand becomes more income sensitive, a smaller change in income is required for any specific change in the interest rate to keep the money sector in equilibrium. Therefore, the LM-curve becomes steeper as money demand becomes more income sensitive. 4.a. A horizontal LM-curve implies that the public is willing to hold whatever money is supplied at any given interest rate. Therefore, changes in income will not affect the equilibrium interest rate in the money sector. But if the interest rate is fixed, we are back to the analysis of the simple Keynesian model used in Chapter 9. In other words, there is no offsetting effect (or crowding-out effect) to fiscal policy. 4.b. A horizontal LM-curve implies that changes in income do not affect interest rates in the money sector. Therefore, if expansionary fiscal policy is implemented, the IS-curve shifts to the right, but the level of investment spending is no longer negatively affected by rising interest rates, that is, there is no crowding-out effect. In terms of Figure 10-3, the interest rate not longer serves as the link between the goods and assets markets. 4.c. A horizontal LM-curve results if the public is willing to hold whatever money balances are supplied at a given interest rate. This situation is called the liquidity trap. Similarly, if the Bank of Canada is prepared to peg the interest rate at a certain level, then any change in income will be accompanied by an appropriate change in money supply. This will lead to continuous shifts in the LM-curve, which is equivalent to having a horizontal LM-curve, since the interest rate will never change. 5. From the material presented in the text we know that when intended spending becomes more interest sensitive, then the IS-curve becomes flatter. Now assume that an increase in the interest rate stimulates saving and therefore reduces the level of consumption. This means that now not only investment spending but also consumption is negatively affected by an increase in the interest rate. In other words, the [C+I+G+NX]-line in the Keynesian cross diagram will now shift down further than previously and the level of equilibrium income will decrease more than before. In other words, the IS-curve has become flatter. This can also be shown algebraically, since we can now write the consumption function as follows: C = C* + cYD - gi In a simple model of the expenditure sector without income taxes, the equation for aggregate demand will now be AD = Ao + cY - (b + g)i. From Y = AD ==> Y = [1/(1 - c)][Ao - (b + g)i] ==> 3 i = [1/(b + g)]Ao - [(1 - c)/(b + g)]Y Therefore, the slope of the IS-curve has been reduced from (1 - c)/b to (1 - c)/(b + g). 6. In the IS-LM model, a simultaneous decline in interest rates and income can only be caused by a shift of the IS-curve to the left. This shift in the IS-curve could have been caused by a decrease in private spending due to negative business expectations or a decline in consumer confidence. In 1991, the economy was in a recession and firms did not want to invest in new machinery and, since consumer confidence was very low, people were not expected to increase their level of spending. In the IS-LM diagram the adjustment process can be described as follows: Io ↓ ==> Y ↓ (the IS-curve shifts left) ==> md ↓ ==> i ↓ ==> I ↑ ==> Y ↑. Effect: Y ↓ and i ↓ . i i1 ISo LM IS1 i2 0 Y2 Y1 Y Application Questions: 1.a. Each point on the IS-curve represents an equilibrium in the expenditure sector. Therefore the IS-curve can be derived by setting Y = C + I + G = (0.8)[1 - (0.25)]Y + 900 - 50i + 800 = 1,700 + (0.6)Y - 50i ==> (0.4)Y = 1,700 - 50i ==> Y = (2.5)(1,700 - 50i) ==> Y = 4,250 - 125i. 1.b. The IS-curve shows all combinations of the interest rate and the level of output such that the expenditure sector (the goods market) is in equilibrium, that is, intended spending is equal to actual output. A decrease in the interest rate stimulates investment spending, making intended spending greater than actual output. The resulting unintended inventory decrease leads firms to increase their production to the point where actual output is again equal to intended spending. This means that the IS-curve is downward sloping. 1.c. Each point on the LM-curve represents an equilibrium in the money sector. Therefore the LM-curve can be derived by setting real money supply equal to real money demand, that is, M/P = L ==> 500 = (0.25)Y - 62.5i ==> Y = 4(500 + 62.5i) ==> Y = 2,000 + 250i. 4 1.d. The LM-curve shows all combinations of the interest rate and level of output such that the money sector is in equilibrium, that is, the demand for real money balances is equal to the supply of real money balances. An increase in income will increase the demand for real money balances. Given a fixed real money supply, this will lead to an increase in interest rates, which will then reduce the quantity of real money balances demanded until the money market clears. In other words, the LM-curve is upward sloping. 1.e. The level of income (Y) and the interest rate (i) at the equilibrium are determined by the intersection of the IS-curve with the LM-curve. At this point, the expenditure sector and the money sector are both in equilibrium simultaneously. From IS = LM ==> 4,250 - 125i = 2,000 + 250i ==> 2,250 = 375I ==> i = 6 ==> Y = 4,250 - 125*6 = 4,250 - 750 ==> Y = 3,500 Check: Y = 2,000 + 250*6 = 2,000 + 1,500 = 3,500 i 125 IS LM 6 0 2,000 3,500 4,250 Y 2.a. As we have seen in 1.a., the value of the expenditure multiplier is α = 2.5. This multiplier α is derived in the same way as in Chapter 9. But now intended spending also depends on the interest rate, so we no longer have Y = αAo, but rather Y = α(Ao - bi) = (1/[1 - c + ct])(Ao - bi) ==> Y = (2.5)(1,700 - 50i) = 4,250 - 125i. 2.b. This can be answered most easily with a numerical example. Assume that government purchases increase by ∆G = 300. The IS-curve shifts parallel to the right by ==> ∆IS = (2.5)(300) = 750. Therefore IS': Y = 5,000 - 125i From IS' = LM ==> 5,000 - 125i = 2,000 + 250i ==> 375i = 3,000 ==> i = 8 ==> Y = 2,000 + 250*8 ==> Y = 4,000 ==> ∆Y = 500 When interest rates are assumed to be constant, the size of the multiplier is equal to α = 2.5, that is, (∆Y)/(∆G) = 750/300 = 2.5. But when interest rates are allowed to vary, the size of the multiplier is reduced to α1 = (∆Y)/(∆G) = 500/300 = 1.67. 5 2.c. Since an increase in government purchases by ∆G = 300 causes a change in the interest rate of 2 percentage points, government spending has to change by ∆G = 150 to increase the interest rate by 1 percentage point. 2.d. The simple multiplier α in 2.a. shows the magnitude of the horizontal shift in the IS-curve, given a change in autonomous spending by one unit. But an increase in income increases money demand and the interest rate. The increase in the interest rate crowds out some investment spending and this has a dampening effect on income. The multiplier effect in 2.b. is therefore smaller than the multiplier effect in 2.a. 3.a. The LM-curve becomes flatter as money supply becomes interest sensitive. Any increase in income will lead to an increase in money demand, which will drive up the interest rate. But the higher interest rates will not only reduce the demand for money but also increase the supply of money. Thus a smaller increase in the interest rate than before is required to bring the money sector back into equilibrium. This means that the LM-curve is flatter. 3.b. If the central bank believes that private spending is very interest sensitive, it is more likely to pursue policies that are intended to keep interest rates from fluctuating. If the central bank believes that most economic disturbances result from changes in money demand (causing the LM-curve to shift), then it is more likely to increase money supply in response to higher interest rates. In other words, if the Bank of Canada accommodates an increase in money demand by increasing money supply, then neither income nor the interest rate will be affected. On the other hand, a disturbance can also come from the expenditure sector, in which case the IS-curve will shift. If interest rates increase due to higher desired spending, then the rise in interest rates can again be kept in check if the Bank of Canada responds by increasing money supply. This time, however, the overall increase in the level of output demanded will now be even larger due the expansionary monetary policy and this may not be desirable. 4.a. An increase in the income tax rate (t) will reduce the size of the expenditure multiplier (α). But as the multiplier becomes smaller, the IS-curve becomes steeper. As we can see from the equation for the IS-curve, this is not a parallel shift but rather a rotation around the vertical intercept. Y = α(Ao - bi) = [1/(1 - c + ct)](Ao - bi) ==> i = (1/b)Ao - (α/b)Y = (1/b)Ao - (1/b)[1 - c + ct]Y 4.b. If the IS-curve shifts to the left and becomes steeper, the equilibrium income level will decrease. A higher tax rate reduces private spending and this will lower national income. 4.c. When the income tax rate is increased, the equilibrium interest rate will also decrease. The adjustment to the new equilibrium can be expressed as follows (see graph on the next page): t up ==> C down ==> Y down ==> md down ==> i down ==> I up ==> Y up. Effect: Y ↓ and i ↓ 6 i IS1 ISo LM i1 i2 0 Y2 Y1 Y 5.a. If money demand is less interest sensitive, then the LM-curve is steeper and monetary policy changes affect equilibrium income to a larger degree. If money supply is assumed to be fixed, the adjustment to a new equilibrium in the money sector has to come solely through changes in money demand. If money demand is less interest sensitive, any increase in money supply requires a larger increase in income and a larger decrease in the interest rate in order to bring the money sector into a new equilibrium. i i IS LM1 LM2 IS LM1 i1 i1 i2 i2 0 Y1 Y2 Y 0 LM2 Y1 Y2 Y The adjustment process in each of the two diagrams is the same; however, in the case of a more interest-sensitive money demand (a flatter LM-curve), the change in Y and i will be smaller. (M/P) up ==> i down ==> I up ==> Y up ==> md up ==> i up Effect: Y↑ and i ↓ Section 10-5 derives the equation for the LM-curve and the equation for the monetary policy multiplier as i = (1/h)[kY - (M/P)] and (∆Y)/∆(M/P) = (b/h)γ respectively. If money demand becomes more interest sensitive, the value of h becomes larger and the slope of the LM-curve becomes flatter, while the size of the monetary policy multiplier becomes smaller. 7 5.b. An increase in money supply drives interest rates down. This decrease in interest rates will stimulate intended spending and thus income. If money demand becomes less interest sensitive, a larger increase in income is required to bring the money sector into equilibrium. But this implies that the overall decrease in the interest rate has to be larger, given that the interest sensitivity of spending has not changed. 6. The price adjustment, that is, the movement along the AD-curve, can be explained in the following way: With nominal money supply (M) fixed, real money balances (M/P) will decrease as the price level (P) increases. There is an excess demand for money and interest rates will rise. This will lead to a decrease in investment spending and thus the level of output demanded will decrease. In other words, the LM-curve will shift to the left as real money balances decrease. 7. In the classical case, the AS-curve is vertical. Therefore, any increase in aggregate demand due to expansionary monetary policy will, in the long run, not lead to any increase in output but simply lead to an increase in the price level. An increase in money supply will first shift the LM-curve to the right. This implies a shift of the AD-curve to the right. Therefore we have excess demand for goods and services and prices will begin to rise. But as the price level rises, real money balances will begin to fall again, eventually returning to their original level. Therefore, the shift of the LM-curve to the right due to the expansionary monetary policy and the resulting shift of the AD-curve will be exactly offset by a shift of the LM-curve to the left and a movement along the AD-curve to the new long-run equilibrium due to the price adjustment. At this new long-run equilibrium, the level of output and interest rates will not have changed while the price level will have changed proportionally to the nominal money supply, leaving real money balances unchanged. In other words, money is neutral in the long run (the classical case). 8.a. An increase in the demand for money will shift the LM-curve to the left, raising the interest rate and lowering the level of output demanded. As a result, the AD-curve will also shift to the left. In the Keynesian case, the price level is assumed to be fixed, that is, the AS-curve is horizontal. In this case, the decrease in income in the AD-AS diagram is equivalent to the decrease in income in the IS-LM diagram, since there is no price adjustment, that is, the real balance effect does not come into play. 8.b. An increase in the demand for money will shift the LM-curve to the left, raising the interest rate and lowering the level of output demanded. As a result, the AD-curve will also shift to the left. In the classical case, the level of output will not change, since the AS-curve is vertical. In this case, the shift in the AD-curve will simply be reflected in a price decrease, but the level of output will remain unchanged. The real balance effect causes the LM-curve to shift back to its original level, since the price decrease causes an increase in real money balances.