The Anatomy of a Traffic Stop: Lessons after Rodriguez v. United

advertisement

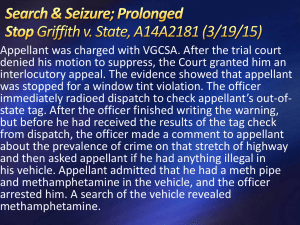

The Anatomy of a Traffic Stop: Lessons after Rodriguez v. United States NCDAA June Seminar June 19, 2015 The Starting Point: The Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution protects citizens against “unreasonable searches and seizures.” U.S. Const. Amend. IV. A traffic stop effectuates a seizure against a driver and any passengers in the vehicle, giving each of them standing to challenge the legality of the stop. Delaware v. Prouse, 440 U.S. 648 (1979) (traffic stop is a “seizure” under the Fourth Amendment); Brendlin v. California, 551 U.S. 648 (2007) (passenger is seized during traffic stop for purposes of the Fourth Amendment). The “Anatomy” of a Traffic Stop: A. The Initial Stop Traffic stops typically occur under one of two circumstances. First, an officer may stop a vehicle if she has probable cause or reasonable suspicion to believe that the driver has committed a traffic violation. Whren v. United States, 517 U.S. 806 (1996). The fact that an officer may have a motive other than a desire to enforce the traffic code does not invalidate the stop under the Fourth Amendment. Id. at 818. “Subjective intentions play no role in ordinary, probable-cause Fourth Amendment analysis.” Id. Officers may also stop motorists at a checkpoint, provided the checkpoint is designed for a permissible purpose. The Supreme Court has approved fixed Border Patrol checkpoints designed to intercept illegal aliens, sobriety checkpoints aimed at removing drunk drivers from the road, and roadblocks established for the purpose of verifying a driver’s license and vehicle registration. See United States v. MartinezFuerte, 428 U.S. 543 (1976) (border checkpoints); Michigan Dept. of State Police v. Sitz, 496 U.S. 444 (1990) (sobriety checkpoints); Delaware v. Prouse, 440 U.S. 648 (1979) (license/registration checkpoints). However, the Fourth Amendment does not permit checkpoints “whose primary purpose [is] to detect evidence of ordinary criminal wrongdoing.” City of Indianapolis v. Edmond, 531 U.S. 32 (2000). Moreover, even checkpoints established for a permissible purpose may be invalid if the resulting stops are overly intrusive or the checkpoint protocol is not systematically enforced. See Prouse, 440 U.S. at 661; State v. Piper, 855 N.W.2d 1 (Neb. 2014)). In order to challenge to a traffic stop on the basis that the officer lacked probable cause or reasonable suspicion that a traffic violation occurred, counsel must either challenge the officer’s observations or demonstrate that the conduct for which the driver was stopped does not, in fact, violate a traffic law. However, an officer is permitted a “reasonable” mistake of law as to what conduct is covered by a particular provision of the traffic code. Heien v. United States, 135 S. Ct. 530 (2014). Therefore, in addition to showing that the law was not actually violated, defense counsel must show that an officer’s interpretation of the statute was not reasonable. Id. at 541 (Kagan, J., concurring). Challengers to checkpoint stops typically allege that the checkpoint was set up for a crime-detection purpose or that it was improperly implemented by officers in the field. To determine whether officer discretion was properly constrained at the checkpoint, courts will consider “whether the checkpoint was approved and whether it was operated in accordance with the approved plan and [ ] policy, as well as any other circumstances that may indicate the exercise of unfettered discretion.” Piper, 855 N.W.2d at 13. B. The Traffic Investigation Prior to the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Rodriguez v. United States, 135 S. Ct 1609 (2015), the Nebraska Supreme Court had held that a traffic investigation may include “asking the driver for an operator's license and registration, requesting that the driver sit in the patrol car, and asking the driver about the purpose and destination of his or her travel.” State v. Howard, 803 N.W.2d 450, 460 (Neb. 2011). The officer was also permitted to “run a computer check to determine whether the vehicle involved in the stop ha[d] been stolen and whether there [were] outstanding warrants for any of its occupants.” Id. Eighth Circuit precedent authorized similar inquiries as part of a routine traffic stop. See, e.g., United States v. Garcia, 613 F.3d 749 (8th Cir. 2010). Rodriguez arguably takes a narrower view of the actions that make up a routine traffic investigation. Under Rodriguez, the authority to hold detain a driver during a traffic stop is defined by the stop’s “mission”– “to address the traffic violation that warranted the stop . . . and attend to related safety concerns.” Rodriguez, 135 S. Ct. at 1614. The Supreme Court in Rodriguez held that an officer’s mission includes “‘ordinary inquiries incident to [the traffic] stop,’” which “typically” involve “checking the driver’s license, determining whether there are outstanding warrants against the driver, and inspecting the automobile’s registration and proof of insurance.” Id. at 1615. Rodriguez does not prohibit unrelated inquiries or actions such as dog sniffs on the basis that they exceed the scope of a routine traffic investigation. Nonetheless, Rodriguez makes it clear that actions not considered part of the “mission” will render the traffic stop unconstitutional if they add time to the stop. Thus, the appropriate inquiry is whether the unrelated inquiries or activities extended the duration of the stop. Id. at 1616. Under Rodriguez, “[a]uthority for the seizure . . . ends when tasks tied to the traffic infraction are–or reasonably should have been–completed.” Id. at 1614. It is important to examine whether the officer’s extracurricular questioning or activities interfered with or delayed the officer while she was should have been addressing her “mission.” When that occurs, Rodriguez holds that the traffic investigation violates the Fourth Amendment. C. Post-Stop Detentions The question presented in Rodriguez was whether an officer may detain a driver after all traffic-related tasks have been completed in order to run a drug detection dog around the vehicle. Prior to Rodriguez, the Eighth Circuit had permitted “de minimis” detentions for that purpose–a rule that had led to suspicionless detentions of up to 10 minutes. See e.g., United States v. Martin, 411 F.3d 998 (8th Cir. 2005); United States v. Morgan, 270 F.3d 625 (8th Cir. 2001); United States v. 404,905.00 in Currency, 182 F.3d 643 (8th Cir. 1999). The Court in Rodriguez found that such detentions, however brief, are unlawful in the absence of reasonable suspicion of criminal activity. Rodriguez, 135 S. Ct. at 1615. The question whether an officer is truly entering into a “post-stop detention” or an unlawfully prolonged investigation does not turn on whether, or when, a traffic ticket has been issued. As the Court explained in Rodriguez, “the critical question . . . is whether conducting the sniff ‘prolongs’–i.e., adds time to–‘the stop.’” Id. at 1616. As explained above, “the stop” is defined by its mission and the inquiries “incident to” accomplishing that mission. Id. at 1615. Once those inquiries are–or should have been–completed, “the stop” ends and any additional detention requires reasonable suspicion or consent. D. Canine Sniffs If the traffic stop ends with a canine sniff, defense counsel may challenge that sniff and any resulting search even if they were not the product of an unlawful detention, as they were in Rodriguez. Under both federal and state law, a positive alert from a canine may provide probable cause for the search of a vehicle. Florida v. Harris, 133 S. Ct. 1050 (2013); State v. Howard, 803 N.W.2d 450 (Neb. 2011). In fact, according to the Supreme Court’s decision in Harris, if a bona fide organization has certified a dog after testing his reliability in a controlled setting, or if the dog has recently completed a training program, the court may presume that the dog’s alert provides probable cause to search. Id. at 1057. However, a defendant may rebut that presumption with contrary evidence of the dog’s unreliability. Id. Evidence that the certification or training program was inadequate, or that its standards were too lax and its methods faulty, is the best evidence to present in order to rebut the presumption. Harris, 133 S. Ct. at 1058. But the court will also accept as proof of unreliability evidence that the dog performed poorly in training, that the dog’s history in the field was inconsistent, and/or that the handler was cueing the dog while conducting the sniff. Id. “The question—similar to every inquiry into probable cause—is whether all the facts surrounding a dog's alert, viewed through the lens of common sense, would make a reasonably prudent person think that a search would reveal contraband or evidence of a crime.” Id. at 1058.