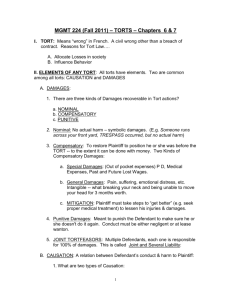

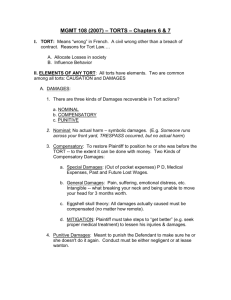

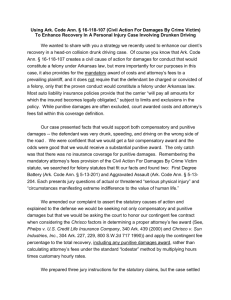

palsgraf, punitive damages, and preemption

advertisement