early menarche: trends, risks and possible causes

advertisement

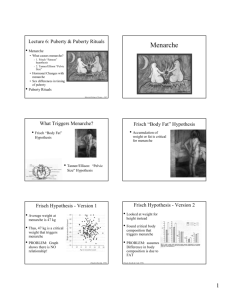

CHECK THE RESEARCH Prepared by SIECCAN (The Sex Information and Education Council of Canada) EARLY MENARCHE: TRENDS, RISKS AND POSSIBLE CAUSES Menarche, or the age at which girls begin to menstruate, has been gradually but steadily falling since the mid-19th century. Researchers have explored various reasons for this decline, ranging from improved nutrition, environmental toxins, and psychosocial stressors. Most studies suggest that a number of factors likely interact to affect the timing of menarche and other markers of puberty. Early menarche and early puberty raise a number of issues for the health and well-being of girls and women. In this issue of Check the Research, we will examine demographic trends on the timing of menarche, as well as discuss some the recent research on possible factors that may affect the age of onset of menarche and puberty. THE MARKERS OF PUBERTY Puberty is marked by the development of breast tissue (thelarche), growth of pubic hair (pubarche) and the beginning of menstruation (menarche). The hypothalamus region of the brain secretes gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) which starts the process of thelarche and menarche. The secretion of this hormone is, in turn, affected by hormones, enzymes and neurotransmitters in the brain. Breast development is the first sign of puberty and it is beginning, on average, one to two years earlier than it did in the mid-20th century (Biro, Greenspan, & Galvez, 2012). While the average age of menarche has also fallen, it has not fallen as dramatically as has the average age of thelarche. According to Steinbraber (2007), studies of American children indicate that the mean age of thelarche is 10 years for white girls and 9 years for black girls and that the process of puberty, from the start of breast and pubic hair development to menstruation now starts earlier and takes longer to complete. STATISTICAL TRENDS Statistics on the age of menarche date from the early 19th century (Tanner, 1968). These early studies often surveyed female patients in hospitals in continental Europe and Great Britain who recalled from memory how old they were when their menstruation began. These studies suggested that the average age of menarche ranged from 16 to 17 years. It has been noted, however, that since memory is not always reliable these findings may have been subject to recall bias. As well, most studies during this period focussed on socioeconomically disadvantaged women and since poor nutrition has been associated with delayed menstruation, this could explain why the average age of menarche reported was quite high in comparison to more recent statistics. CURRENT STATISTICS Research from the 20th and 21st centuries shows a steady decline in the average age of first menarche. According to Steingraber (2007), since the nineteenth century, the average age of first menarche has declined at the rate of approximately 4 months a decade. A study from the United States indicated an average age of first menarche of 12.3 years, with variations based on race and ethnicity; white girls had an average age of first menarche of 12.52 years, NonHispanic black girls 12.06 years and Mexican-American girls 12.09 years (Andersen & Must, 2005). Statistics from Europe indicate an average age of menarche that ranges from 12.3 years in Greece to 13.3 years in Finland (Steingraber). Other international statistics on the average age of menarche include 13.0 years for Australia, 13.0 years for Russia and 13.2 years for Norway (Al-Sahab, Arden, Hamadeh, & Tamin, 2010). CANADIAN STATISTICS Canadian statistics related to menarche have usually come from relatively small, regional studies. For example, an Ontario study on the relationship between nutrition and menarche followed a cohort of 589 premenarchal girls from February 2013 CHECK THE RESEARCH Prepared by SIECCAN (The Sex Information and Education Council of Canada) the years 1992 to 1996 (Koo, Rohan, Jain, McLaughlin, & Corey, 2002). Among the 189 girls who reached menarche during the course of the study, the median age of onset was 13.6 years. A similar Quebec study on the relationship between diet and menarche, followed a cohort of 2,390 pre-menarchal girls for the years 1986-1988 (Moisan, Meyer, & Gingras, 1990) . At the end of the study, 39.6% of the girls had reached menarche, with the median age of this group being 12.1 years. The first national study on the age of menarche among Canadian adolescent girls was based on statistics from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY). This survey by Statistics Canada and Human Resources and Social Development Canada began in 1994 with a sample of children aged 0 to 11 years. At two year intervals, the study followed up the children and administered questionnaires on various topics related to growth and development. For the years 2001/2002 the NLSCY surveyed 1,403 girls aged 14 to 17 about their age of menarche. Al-Sahab et al. (2010) analyzed the responses of the survey and found the mean (average) age of menarche to be 12.72 years and the median age to be 12.67 years. They also noted considerable variation in age of menarche across the provinces. British Columbia had the lowest rate of early menarche (less than 11.53 years), and New Brunswick, PEI, and Quebec had the highest. Ontario had the highest rate of late menarche (greater than 13.91 years), and Alberta had the lowest. Al-Sahab et al. (2010) found that the only socio-economic variables associated with age of menarche were income and family composition (i.e., whether the children lived with one or two parents). High income was associated with lower rates of early menarche. The authors speculate that while higher income improves nutritional status, which has been linked to early menarche, there are lower rates of obesity in higher income children and obesity has also been associated with early menarche. Girls who lived in families with an absent father were more likely to experience an early menarche. This relationship between father absence and early menarche has also been noted in US studies (Steingraber, 2007). It has been hypothesized that living in a single parent family increases both physical and psychological stress, which in turn affect the timing of metabolic changes related to menarche (Belsky, Steinberg, & Draper, 1991). EFFECTS OF EARLY PUBERTY/MENARCHE Several studies have indicated that women who have an early menarche are at increased risk for breast cancer (Walvoord, 2010). According to Steingraber (2007), researchers have speculated that with early menarche a woman’s lifetime exposure to estrogen is increased, and exposure to estrogen increases the risk of breast cancer. The early appearance of pubic hair (pubarche) has been linked to polycystic ovary syndrome in adulthood, which causes pelvic pain and infertility. Those who suffer from this syndrome are also at a higher risk for diabetes (Steingraber). Some studies have also drawn links between early age of menarche and increased risk for psychosocial distress such as depression, eating disorders, earlier sexual initiation, and substance abuse (Steingraber, 2007). However, some researchers have also noted that the incidence of these problems may level off as these girls age, so that by late adolescence there is little difference between girls who mature early and those who mature later. A recent study of Canadian girls found no association between age of menarche and substance abuse. The factors that did affect the rate of substance abuse were satisfaction with school and the quality of the father-daughter relationship. ( Al-Sahab et al. , 2012). POSSIBLE CAUSES OF EARLY MENARCHE/PUBERTY The timing of puberty can be affected by genetic and environmental factors. One of the strongest predictors of age of menarche is the age at which a child’s mother attained menarche. As noted above, Racial and ethnic factors may also influence the age of menarche. Some environmental factors that have been associated with early puberty are nutrition, pollution, exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals, stressful life events, family relationships, socioeconomic status, weight, premature birth, and low birth rate (Walvoord, 2010). February 2013 CHECK THE RESEARCH Prepared by SIECCAN (The Sex Information and Education Council of Canada) “EARLY PUBERTY IS A PROBLEM THAT DOES NOT ARISE FROM A SINGLE TOXICANT, LIFESTYLE OR DIETARY SHORTCOMING. RATHER, MANY DIFFERENT ENVIRONMENTAL STRESSORS – SOME PSYCHOSOCIAL, SOME NUTRITIONAL, SOME CHEMICALINTERACT IN THE BODIES OF YOUNG GIRLS IN WAYS THAT RESULT IN ACCELERATED SEXUAL MATURATION WITH ITS ATTENDANT RISKS FOR HEALTH AND WELL-BEING.” (Steingraber, 2007, p. 14) Several studies have linked television viewing and computer use with the early onset of puberty (Salti et al., 2006; Sigman, 2007). Researchers have speculated that television viewing and computer use disrupts the production of melatonin, a hormone that plays a role in the timing of puberty. Melatonin affects the body’s circadian rhythms such as sleep patterns, body temperatures, and the release of hormones. The production of melatonin is affected by light levels, increasing when it is dark. The levels of light emitted by televisions, computer screens and other electronic devices may be enough to inhibit melatonin production. Low levels of melatonin have been found among girls who experience puberty at an early age. According to DiVall (2013), exposure to endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) during the fetal and perinatal periods can have an effect on pubertal timing. EDCs are chemicals found in many everyday items such as pesticides, cosmetics, plastic toys and food containers as well as in industrial by-products and flame retardants used in the production of furniture, mattresses, and some clothing. Endocrine disrupters interfere with the functioning of the endocrine system, which regulates the growth and development of the body. The hormones that stimulate and drive pubertal changes are part of the endocrine system. It is difficult to isolate the effects of specific EDCs on human growth since individuals are exposed to a number of compounds during their lives, starting with fetal and perinatal exposure. There is some evidence linking prenatal exposure to EDCs and low birth weight (DiVall, 2013). Researchers have also noted a possible link between environmental contaminants and the obesity epidemic in the United States (Biro, Greenspan, & Galvez, 2012). Low birth weight and obesity have both been associated with early menarche. Rapid weight gain following a low birth weight has also been linked to early menarche (Steingraber). Studies have also linked early menarche to consumption of animal fat, formula feeding, inactivity and as mentioned previously, low income and family stressors such as lack of a father (Steingraber). It is apparent that many of the risk factors for early menarche and puberty are over-represented in disadvantaged populations. “ALL OF THE STRESSORS … THAT APPEAR TO CONTRIBUTE TO EARLY PUBERTY IN GIRLS—OBESITY, TELEVISION VIEWING, SEDENTARINESS, FAMILY DYSFUNCTION, PRETERM BIRTH, FORMULA-FEEDING, CHEMICAL EXPOSURES—ARE HIGHER IN POOR COMMUNITIES AND COMMUNITIES OF COLOR WHERE POVERTY, RACISM, UNEMPLOYMENT AND TOXIC SUBSTANCE EXPOSURES ARE HIGH AND ACCESS TO NOURISHING FOOD AND SAFE PLACES TO EXERCISE IS LOW.” (Steinbraber, 2007, p. 60) February 2013 CHECK THE RESEARCH Prepared by SIECCAN (The Sex Information and Education Council of Canada) WHAT’S THE TAKE HOME MESSAGE? The age of menarche has been steadily decreasing since the mid-19th century. Studies point to various social and health-related consequences associated with early menarche. Researchers generally agree that the reasons behind this steady decline in the age of menarche are multifaceted and involve a range of genetic and environmental influences. Many risk factors for early menarche are often tied to conditions of poverty and include exposure to toxic chemicals, poor nutrition, obesity and psychosocial stressors. The role of endocrine disruptors in contributing to early menarche and puberty is an ongoing area of interest for researchers. REFERENCES Al-Sahab, B., Ardern, C., Hamadeh, M. & Tamim, H. (2010). Age at menarche in Canada: Results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children & Youth. BMC Public Health, 10:736. (doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-736) Al-Sahab, B., Ardern, C., Hamadeh, M. & H. Tamim. (2012). Age at menarche and current substance use among Canadian adolescent girls: Results of a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 2012 12:195. Anderson, S. & Must, A. (2005). Interpreting the continued decline in the average age at menarche: Results from two nationally representative surveys of U.S. girls studied 10 years apart. Journal of Pediatrics, 147, 753-760. Belsky, J., Steinberg, L., & Draper, P. (1991). Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Development, 62, 647-670. Biro, F., Greenspan, L., & Galvez, M. (2012). Puberty in girls of the 21st century. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 25, 289-294. DiVall, S. (2013). The influence of endocrine disruptors on growth and development of children. Current Opinions in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, 20, 50–55 Koo, M., Rohan, T., Jain, M., McLaughlin, J. & Corey, P. (2002). A cohort study of dietary fibre intake and menarche. Public Health Nutrition, 5, 353-360. Moisan, J., Meyer, F. & Gingras, S. (1990). Diet and age at menarche. Cancer Causes and Control, 1, 149-154. Salti, R., Tarquini, R., Stagi, S., Perfetto, F., Cornelissen, G, Laffi, G., Mazzoccoli, G., & Halberg, F. (2006). Age-dependent association of exposure to television screen with children’s urinary melatonin excretion? Neuroendocrinology Letters, 27, 73-80. Steingraber, S. (2007). The falling age of puberty in U.S. girls: What we know, what we need to know. San Francisco, CA: Breast Cancer Fund. Sigman, A. (2007). Visual voodoo: The biological impact of watching TV. Biologist, 54, 12-17. Tanner, J. (1968). Early maturation in man. Scientific American, 218, 21-27. Walvoord, E. (2010). The timing of puberty: Is it changing? Does it matter? Journal of Adolescent Health, 47, 433-439. February 2013