Sensori-motor period

advertisement

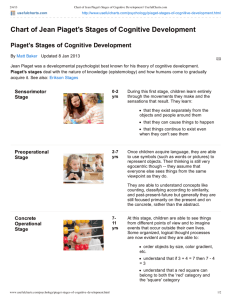

Cognitive Development – Piaget Sensori-motor period – 0 to 24 mo. Sensory awareness and motor actions Prior to the development of language, children’s knowledge is embedded in their sensory and motor systems. Regularities develop, or sensori-motor schemas Three things to keep in mind when considering the following 6 stages: 1. Each describes the most advanced level of performance for each stage 2. Age ranges are only approximate. The sequence is more important 3. These stages only represent one way of describing infant cognitive development The use of locution "circular reactions" here emphasizes that the child is operating on the world and receives feedback. When a behavior produces an interesting event, it is repeated. Stumbling onto a new experience caused by baby’s own motor activity. Stage 1: Reflexes (birth to 1 month) "Genetically programmed" reflexes. Minor refinements of these reflexes occurs in first month. A continuation of what happens in the womb. Behaviors that were in some sense "available" are now exercised. Eye movements, sucking, grasping, larger movements of arms and hands. No truly new behaviors are learned in this period, only minor refinements. Piaget believed these provide the building blocks for later development. Stage 2: Simple actions (primary circular reactions, 1 to 4 months) A circular reaction is a behavior producing an event that leads to the behavior's being repeated. The end of one sequence triggers the start of another. 1 Ex. Malcolm waving his hand…brushing his cheek…movement becomes abbreviated…hand goes in mouth…sucking occurs. “One evening when John was putting 2-month-old Malcolm to bed, he noticed Malcolm moving his arms in a seemingly random but rhythmic up-and-down pattern. As his right hand brushed against his face, he turned his head to the right and his arm movements became smaller. The next time his hand brushed against his face, he opened his mouth and captured it. After sucking for a while he released the hand, moved it up and down again, and then recaptured it with his mouth. Over and over Malcolm repeated this sequence. John was observing a type of sensorimotor scheme Piaget called a primary circular reaction.” Primary circular reaction involves one's own body. Thumb sucking. Infants seem to be trying to gain control over events that originally occurred by accident. Sucking does not continue, but the child tends to repeat the action that led to getting the thumb in the mouth. Their own activities seem to generate and select information useful for development. Coordinating separate actions, self-interest, reproduction of the actions. Mouth opens differently for nipple than for spoon. Begin to anticipate events – hunger cry stops when mom comes in room. Adaptations oriented towards one’s own body and motivated by basic needs. Stage 3: Actions on objects (secondary circular reactions, 4 to 8 months) At this time, infants sit up and become skilled at reaching for, grasping and manipulating objects. Turning their attention to the environment. Infants investigating the effects their actions have on external objects. Reproduction of interesting external events. Piaget’s description of his son Laurent and the rattle: “Piaget tied a string from Laurent’s wrist to a rattle suspended above his crib. If Laurent moved his arm vigorously, the rattle made a noise. By randomly waving his arms, Laurent soon caused the rattling sound. At this point he stopped, listened, and then moved his whole body so the sound occurred again. Repeating this secondary circular reaction, Laurent gradually adapted his movements until he moved only the appropriate arm. The next day Piaget again tied the string from Laurent’s wrist to the rattle, but Laurent did not spontaneously move his arm. Only after his father shook the rattle did Laurent revive the previous day’s circular reaction. On the third day Piaget tied the string to Laurent’s other wrist. Again Piaget had to reinstate the circular reaction by shaking the rattle. When Laurent began moving his arm, it was the one without the string. When no sound resulted, he moved his 2 body more extensively until he heard the rattle. As Laurent repeated the circular reaction, he again adapted his movements until he eventually moved only the arm connected to the rattle.” He is learning a connection between a motor movement and a consequence, but only has a dim cognitive understanding of the relationship. A sensori-motor pairing. Child can now initiate behaviors that allow them to learn about their world. Behaviors appear that are assembled out of two previously present behaviors, such as visual tracking and hand reaching. Simple imitation of others occurs if it is a behavior already available. Cannot imitate new behaviors. Stage 4: Coordination of Actions (Coordination of Secondary Schemes, 8 to 12 months) At 7 months, Meryl got very frustrated if she wanted a toy and some other object was blocking the way. Karen thought it was strange Meryl made such a fuss instead of moving the unwanted object, but she figured it was just Meryl’s cranky nature. Two months later, one day Karen saw Meryl crawling toward the television plug. To distract her, Karen quickly placed a large toy dog in front of the socket. To her surprise, this tactic failed completely. With a sweep of her arm, Meryl knocked the dog out of the way and reached for the cord. Actions put together in goal-directed chains. Behaving not for itself but in order to obtain something. (child can now knock something out of the way to get to something else) This is a form of anticipating consequences. First sign of purposefulness. "Coordination of Secondary Schemes" because child is coordinating schemes applied to external objects to achieve some goal. e.g. baby can now learn to use a spoon to transport food to mouth. Child now anticipates consequences of action. Intentional, goaldirected behavior. Piaget argues that infants now understand their own behavior enough to imitate actions they seldom perform spontaneously. Can imitate without seeing their own behavior. Babies now appreciate physical causality. Some object permanence – they will search for objects but in a previous hiding place. Stage 5: Exploration by Variations of Actions (Tertiary Circular Reactions, 12 to 18 months) Circular reaction now becomes experimental and creative. 3 “(Piaget’s 1 ½ year-old daughter) Jacqueline had a visit from a little boy of 18 months whom she used to see from time to time, and who, in the course of the afternoon, got into a terrible temper. He screamed as he tried to get out of a playpen and pushed it backward, stamping his feet. Jacqueline stood watching him in amazement, never having witnessed such a scene before. The next day, she herself screamed in her playpen and tried to move it, stamping her foot lightly several times in succession.” Also begins when some action accidentally leads to an interesting sensory consequence. Rather than leading to a more or less exact repetition, child begins to experiment. Discovery of new means and qualities of objects. (ex. Child throwing a ball, then a doll, then a shoe down the stairs). Can now twist and turn an object to fit in a hole. Infants now get into everything in their exploration. Learning new means for reaching goals (means-ends relationships). Children around 18 months of age rapidly acquire tool-using skills. Trial and error approach (pulling a blanket to get a toy on it). More advanced understanding of object permanence. Will look in several places to find an object. Will imitate many more behaviors like stacking blocks, scribbling on paper and making funny faces. Stage 6: Beginnings of Representational Thought (18 to 24 mo.) The forming of mental representations - indicated in such actions as deferred imitation. The ability to make one thing stand for something else. Pretend play. Children also start to solve problems "in their heads" apart from physical action. Inventions of new means through mental combinations. Limited to sensorimotor schemes the child could act out. Challenges to Piaget’s Theory Description considered to be accurate, but explanations have been questioned in the following areas: The timetable for the emergence of cognitive skills The existence of qualitatively distinct developmental stages The range of innate abilities The source of infants’ cognitive limitations Reassessing the Timetable for Infant Development 4 Piaget seemed to underestimate the skills of infants. We can find skills much earlier. Perhaps because he only credited infants with a skill when it was well developed and could be used in a variety of situations. Reassessing the Concept of Stages Stage – infants who are at a particular stage with respect to one task should be at the same stage for other major tasks. Certain general cognitive advances characterize each stage, and these general advances should produce simultaneous progress in a number of different areas. Researchers find a great deal of inconsistency in each baby’s achievements. An infant may be at one stage on one task, but show evidence of another. Piaget had used the term horizontal decalage to refer to the lack of simultaneous development in different areas. Some have suggested that cognitive development is the acquisition of separate specific skills and understandings, rather than progress through global stages. Progress on one particular cognitive task may be to some degree independent of their progress in mastering other tasks. Reassessing Infants’ Inborn Abilities Babies may be born with an understanding of many basic properties of the physical world (Spelke) or with fairly specific learning mechanisms that guide the development of their understanding (Baillargeon) Reassessing Infants’ Cognitive Constraints For Piaget, cognitive development was constrained by their sensori-motor cognitive structures and lack of mental representation. Some argue that there are constraints or limits on information-processing capacity, or working memory. An infant must use this memory to remember things, initiate actions, and control behavior. Development involves expanding capacity due perhaps to brain development or development of habits. Causality and Other Relations Between Objects To what extent can babies understand relations between objects? Needed to make sense of the stream of perceptual information from the world around them. How do they understand causality? Studies of moving objects, impossible situations of things suspended in midair. A rudimentary understanding of the relations between objects appears between 4 and 8 months, applied I simple situations. Complexity and flexibility of understanding increases between 8 and 12 months. Number 5 Starkey and Cooper (1980) – habituated 4-7 mo. olds to either two or three dots. Could distinguish when either another dot was added to 2 or taken away from 3. Could not work with larger numbers. Starkey, Spelke, Gelman (1983) – 6-8 mo. olds would look at arrays of two or three objects depending on how many drum beats there were. Interpreted as meaning that they have an abstract concept of number. Categorization 6