The 2014 Congressional Primaries in Context

advertisement

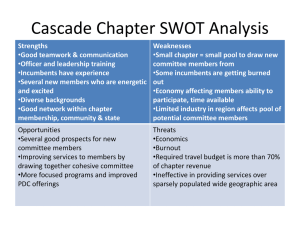

The 2014 Congressional Primaries in Context By Robert G. Boatright Clark University rboatright@clarku.edu Presented at What the 2014 Primaries Foretell About the Future of American Politics Event Co-hosted by The Campaign Finance Institute and The Brookings Institution SEPTEMBER 30, 2014 The 2014 Congressional Primaries in Context Robert G. Boatright Clark University September 30, 2014 rboatright@clarku.edu Congressional primary elections have traditionally received scant attention from policymakers and from political scientists. This is no accident. It is rare for incumbent members of Congress to face opposition from within their own party, and it is still rarer for incumbents to be defeated. Yet over the past decade, a small number of high profile primary challenges have given the impression that the risk of “getting primaried” has increased for moderates of both parties. In 2014, the stunning defeat of House Majority Leader Eric Cantor – the first primary defeat in history of a party leader – provided further ammunition for those who would argue that primary competition has increased. Even before Cantor’s defeat, 2014 was billed as a year in which a “Civil War” would be waged in the Republican Party’s primaries. Tea Party-affiliated organizations drew up lists of incumbents to challenge. Meanwhile, business groups and others concerned with the prospect that the primaries would increase partisan conflict and gridlock announced their intention to support moderates of both parties. Did the 2014 primaries live up to their billing? In this paper I draw upon data collected by the Campaign Finance Institute (CFI) in order to compare the 2014 primaries to those of previous years in regards to their frequency and competitiveness, the number of incumbent defeats, and spending by candidates and outside groups. The results shown here are mixed. The number of primary challenges was higher than has been the norm over the past forty years, but it was lower than in 2014. The number of defeated incumbents in the House and Senate was actually rather low in comparison to prior years. The number of explicitly ideological challenges (as opposed to challenges rooted in other alleged failings of the incumbent) was higher than in any of the 46 years for which I have kept data, and all of these challenges took place within the Republican Party. In other words, there may well have been a civil war, but it was arguably smaller and less successful than one might have expected at the outset of the 2014 primaries. Money, however, played a different role in 2014 than it had in past years. In contrast to previous years, there was no consensus choice for national donors looking to make a statement in primaries. While the overall amount of money contributed to primary challengers increased substantially, this increase was spread across a large number of candidates, and as a result there were few primary challengers who had the financial resources to pose a significant threat to their opponents. It is too early to know if this is a temporary aberration or part of a trend. In the conclusions to this paper, however, I speculate about the reasons for this and the role independent expenditures may have played in changing the national bases for primary candidates. 1 In the discussion below I outline the approach I have taken here in comparing the 2014 primaries to those of prior years. I then discuss House primaries and Senate primaries separately. I focus mainly on challenges to incumbents, but there is some discussion of open seat and challenger primaries. I close with some thoughts on the meaning of apparent changes in the funding of primary challenges. In future papers, CFI will present a more in-depth exploration of the role of independent expenditures in the 2014 primaries. What should we have Expected from the 2014 Primaries? There is nothing new about any of the claims made about the 2014 primaries. In two recent books (Getting Primaried, published by the University of Michigan Press in 2013, and Congressional Primary Elections, published by Routledge in 2014) I analyzed congressional primaries from 1970 through 2012 and drew the following conclusions: - Primary challenges to incumbent members of Congress are more frequent today than they were in the early 2000s and late 1990s, but they are less common than they were in the 1970s or 1980s. Such challenges appear to increase when overall turnover in congressional general elections increases. - The majority of congressional primary challenges are motivated by idiosyncratic failings of the incumbent – factors such as scandals, the incumbent’s age, or the incumbent’s alleged incompetence. Ideological challenges – from the left for Democratic incumbents or from the right for Republican incumbents – constitute an average of just under 14 percent of primary challenges, but they have grown in frequency, particularly within the Republican Party, over the past decade. - There is no evidence that primary challenges are successful either in replacing incumbents or in bringing about change in incumbents’ behavior. Primary challengers are very rarely successful in seeking office, and there is no evidence that challenged legislators change their voting habits in Congress. Anecdotal reports have alleged that some incumbents preemptively change their behavior out of fear of “getting primaried.” This remains a possibility but it is difficult, if not impossible, to measure. - There is compelling evidence that over the past decade a small number of primary challenges – no more than two or three per election cycle – have effectively been “nationalized.” In each cycle since 2006 there have been candidates who stood out not only because of the amount of money they raised, but because they were able to raise a disproportionate amount of their money from out-of-state donors and in small contributions. The majority of independent expenditures in each of these primaries were directed at aiding these same candidates. There are several reasons to expect the 2014 election to represent a break from this pattern. The dominant media narrative for much of early 2014 had to do with the alleged “civil 2 war” between Republican Party leaders and Tea Party conservatives. In addition, 2014 is the third election cycle since the Supreme Court’s Citizens United v. FEC decision, and the increase in independent spending might expected to have increased the flow of money into congressional primaries and to have changed the beneficiaries of independent spending. To monitor such spending as it took place, the Campaign Finance Institute developed an interactive web-based too to track candidate and interest group fundraising and spending. While independent expenditure data are available from the Federal Election Commission, we have sought to supplement these data. Although our analysis of the data is not complete, here I summarize some of our initial findings and I compare these findings to what we know about previous congressional primaries. House of Representatives Primaries Primary Challenges to Incumbents Figure 1 shows the number of incumbents held to 75 percent or less of the primary vote and those held to 60 percent or less of the primary vote in each year since 1970, with incumbentvs.-incumbent races excluded.1 As Figure 1 shows, there were fewer competitive primary challenges to incumbents in 2014 than there were in 2012 according to both measures, but there were more than in 2010. This is noteworthy because in the past there has been a high correlation between the number of incumbents who face competitive primary challengers and the number of incumbents defeated in the general election. Should the 2014 general election conform to most analysts’ predictions and fail produce very much turnover, the 2012 – 2014 period would be only the second pair of elections since 1970 where this relationship was not present. Figure 2 shows this pattern. The pattern suggests there is clearly a link between primary and general election competition, but it is not necessarily intuitive that there should be such a connection. It is hard to come up with definitive proof about any account of the relationship, but my hypothesis in prior work has been that activists within the two parties tend to take out their ideological frustration on members of their own party as well as on the opposite party. Previous instances where there have been highs in both categories have either been “wave” elections such as 1974, 1994, 2006, or 2010, or redistricting years. It is possible that the same sorts of forces that impelled Tea Party-affiliated general election challengers in 2010 also prompt potential candidates with similar views to take on incumbents of their own party. If this is the case, then 2014 may simply represent a continuation of this wave, but one that takes place in a year when many of the Democratic seats that such candidates might aspire to wrest from the Democrats have already been taken. Despite the higher-than-usual number of challenges, however, the number of defeated incumbents was not out of line with the historical average (see Figure 3). This figure does include incumbent-vs.-incumbent races. It has been over thirty years since more than four House incumbents were defeated in a non-redistricting year, but, as the figure shows, during the 1950s, 3 1960s, and 1970s it was common for ten or more incumbents to lose in their primaries each year. By this measure, then, 2014 looks unremarkable. For each election since 1970 I have coded the reasons for primary challenges into twelve different categories, drawing on candidates’ statements, expert analyses of these races, and media accounts. Ideological primary challenges never constitute the majority of primary challenges in any year. Most incumbents are challenged because they are alleged by their opponents to be incompetent, insufficiently attentive to the district, or compromised by a real or perceived scandal. There is no reason to expect the number of such challenges to increase or decrease from election cycle to the next. The number if ideological challenges, however, has increased steadily over the past five election cycles, and was at an historic high in 2014.2 This is entirely due to challenges within the Republican Party; not a single Democratic primary challenger based his or her campaign on the claim that the incumbent was insufficiently liberal. Figure 4 shows the change in the number of ideological challenges since 1970, and Figure 5 compares ideological challengers within the Democratic and Republican parties. This is noteworthy not only for what it says about conflict within the Republican Party, but for what it says about the lack of conflict among Democrats. During the primaries in 2006, 2008, and even 2010, there was a noticeable effort among liberals to recruit challengers to Democrats who had broken with the party on a variety of different liberal priorities, including funding for the Iraq War and support for the Affordable Care Act. Such rhetoric was still a part of liberal politics in 2014, as exemplified by Zephyr Teachout’s challenge to New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, but it was missing entirely from the Democratic House primaries. One should read these party differences with some caution, however. Congressional candidates can be expected to use whatever sorts of appeals are most likely to generate support; it may well be that among Republicans a claim to be more conservative than the incumbent is an effective campaign tactic in 2014 but might not have been as effective in prior years. In addition, such claims also do not indicate that the incumbents who faced challengers were, in fact, as moderate or liberal as their opponents claimed them to be.3 It is worth noting that none of the four successful challenges was a clear case of an ideological challenge. Michigan Representative Kerry Bentivolio reached office in 2012 only because of the unexpected withdrawal from that year’s primary of incumbent Thaddeus McCotter, and was seen by many as an “accidental congressman.” Bentivolio was challenged by a candidate with substantial political experience who framed the race as a referendum on Bentivolio’s competence. Texas Representative Ralph Hall’s advanced age figured in many accounts of his defeat. Massachusetts Democrat John Tierney had received unfavorable media coverage for two years related to a legal scandal involving his wife. And even the Eric Cantor challenge, perhaps the defeat where ideology played the largest role, also was complicated by claims that Cantor was insufficiently attentive to his district and that the 2012 redrawing of his district had worked to Cantor’s disadvantage. I coded the challenge to Cantor as an ideological challenge, but not the other three. The amount of money contributed to primary challengers increased substantially for the second straight year. This is true both in the aggregate – that is the overall money contributed to all challengers – and in terms of the average amount raised by primary challengers. While the 4 inflation-adjusted increases in individual contribution limits in each year since 2002 might be expected to result in some increase across election cycles, it is important to note that the average amount raised by primary challengers actually fell, in non-inflation-adjusted dollars, in 2010 and again in 2012. The increase in 2014, then, shows that on average candidates in 2014 posed more of a threat in financial terms than they had in the past two cycles. As Figure 6 shows, the total amount raised in small contributions (unitemized contributions and itemized contributions of $250 or less) and in itemized amounts from out-of-state contributors also increased in 2014; small contributions went slightly up and out-of-state contributions went up sharply. These two categories, as I have argued in my prior work, are useful metrics in assessing whether a primary campaign has been nationalized – that is, they show whether the candidate has received favorable media attention outside of his or her home state, is the beneficiary of a bundling campaign, or is the beneficiary of online appeals from ideological groups. In contrast to prior years, however, this increase was not driven by the fundraising successes of a small number of candidates. Figure 7 compares the top twenty fundraisers among House primary challengers from 2004 through 2012 to those of 2014. In the 2004-2012 races, it is easy to spot the candidates who were the beneficiaries of national bundling campaigns or internet-based grassroots efforts. In 2012, three of the six best-funded primary challengers were Democrats, none of these six were ideological challengers, and the most successful candidate at raising money from out-of-state donors was successful Democratic primary challenger Seth Moulton. The closest to a nationalized ideological primary challenge for a Republican in the House was Idaho’s Bryan Smith, who ran unsuccessfully against incumbent Mike Simpson. In terms of its funding, this race resembled some of the more vigorous challenges of past years, but, whether because of its location or because of characteristics of the candidates, it did not receive substantial national attention. Of course, ideological donors and interest groups do not solely decide among House primary challengers in making their spending decisions; they may also choose to support House incumbents, House open seat candidates, candidates in House challenger primaries (that is, races for the nomination to face an incumbent in the general election), and/or Senate candidates. Incumbents, Open Seat Candidates, and Challenger Primary Candidates House primary challengers are easy to study for three reasons: they are uncommon, they are almost always motivated by easily-identifiable failings of the incumbent, and because they so rarely win, the money spent in their campaigns is almost always aimed at winning the primary. Other types of candidates are less easy to categorize, and many incumbents and candidates in other types of primaries spend money during the primary cycle that is clearly geared toward winning the general election. That is, an incumbent with an uncompetitive opponent, or even an incumbent who regards his or her primary opponent as an irritant but not as someone who is likely to defeat him or her may spend money in the primary for the purpose of campaigning against his or her prospective general election foe. The same holds true for the frontrunner in an open seat primary or a challenger primary (a primary for the nomination to run against an incumbent in the general election). Because of this, it is difficult to analyze such campaigns and it is particularly difficult to draw conclusions about spending in such campaigns. 5 In the case of open seat or challenger campaigns, there is often an “insider vs. outsider” or “establishment vs. insurgent” dynamic, and in some races (most notoriously, the open seat 2010 Senate open seat race in Delaware that pitted Representative Mike Castle against Christine O’Donnell) one candidate may even be the de facto incumbent. In subsequent work we expect to analyze outside group spending decisions with such dynamics in mind. Here, however, I confine the analysis to noting that overall competition in Republican challenger and open seat primaries exceeded that of Democratic primaries for the third election cycle in a row, but that overall competition in these races was down in comparison to 2012. Figure 8 shows this using a “fractionalization index,” a tool developed by political scientists to measure competition in multi-candidate races where a high score indicates a high level of dispersion of the vote among different candidates while a low score represents a substantial advantage for one candidate.4 While competition in open seat races is driven somewhat by the nature of the seats that are open, it is apparent in the time series here that there is more competition in years where a party expects to gain seats. The limited change for Republicans in 2014 open seat primaries, and the decline for both parties in 2014 challenger primaries, may be indicative of the expectation that 2014 will be a low turnover election. The decline of competition in challenger primaries here may be particularly indicative of parties’ perceptions that there are relatively few vulnerable incumbents of either party. The difference between parties, however, is noteworthy, and when coupled with the lack of competition in Democratic incumbent primaries it suggests that the Republican Party is currently experiencing more internal conflict than are Democrats. This is something that has been noted in the media, and it is something that has been framed as an avoidance by the Democratic Party, for now, of divisions that will manifest themselves once the Obama Presidency has concluded. This difference has also been noted by political scientists, who have suggested that the traditional notion of the Democrats’ traditional reputation as the more heterogeneous party may no longer be accurate. Primary competition patterns do not prove either of these notions to be true, but they do suggest that for the time being, Democratic primary frontrunners have an easier path to the nomination than is the case for Republicans. Senate Primaries The 2014 Senate races did feature a relatively high number of competitive primary challengers. There were four competitive Republican challengers, although arguably the most competitive challenger was the lone Democrat, Hawaii Representative Colleen Hanabusa. An additional two Republican incumbents (Lindsey Graham of South Carolina and John Cornyn of Texas) received low primary vote shares but won comfortably because they were running against multiple challengers who split the anti-incumbent vote. Because there are fewer Senate primaries than House primaries in any given year, and because the idiosyncrasies of the states holding them and the incumbents running in them thus take on greater importance, it is hard to measure trends in Senate primaries. There is clearly not 6 a pattern in incumbent defeats; there were no incumbents defeated in the 2014 primaries, but there has only been one election cycle since 1980 where as many as two incumbents lost their primaries, and the last instance where a primary challenger defeated an incumbent and then went on to win the general election took place in 2002. One could conclude from the six instances where Republican incumbents were held to less than 75 percent of the vote that the same sort of trend seen in Republican House races is manifesting itself in Senate races. If one were to draw such a conclusion, however, one would need to then explain why in 2012, when the number of House primary challenges was higher than in 2014, there were only two competitive Senate challenges. In short, it is hard to use Senate primaries as a barometer of any sort of national when they could be a reflection of a small number of weak incumbents. What is clear from the 2014 data, however, is that some Senate primary challengers did attract the sort of donors who were absent in the 2014 House races. Overall fundraising by Senate primary challengers was up in comparison to 2012, a function of the larger number of candidates. The fundraising by these candidates was different from the norm in the House or the Senate, however. Senate primary candidates have historically relied more heavily on selffinancing than have House candidates, but this was not the case in 2014. The five Senate primary challengers who exceeded 25 percent of the vote also showed signs of having nationalized their campaigns. Figure 9 shows that as many as three of the four Republican challengers were the beneficiaries of national fundraising campaigns. Hawaii Democrat Colleen Hanabusa, a member of the House seeking a Senate seat, also raised a substantial amount of money from out-of-state donors; the percentage of her funds that came from out-of-state donors in the Senate race was higher than her fundraising from out-of-state donors had been in her previous House campaigns. Figure 10 shows the level of fractionalization in challenger and open seat Senate primaries. Like incumbent primaries, variations from one year to the next in competition in Senate open seat and challenger primaries can also be strongly influenced by a small number of races. There were, for instance, seven open seat primaries, five of which were in Republicanleaning states. Unsurprisingly, the level of competition was higher in Republican open seat races than in Democratic ones. Republican open seat primaries have been more contentious than Democratic open seat races in all but one of the past ten election cycles, but the difference has been particularly dramatic since 2010. As it did in the House, competition declined in both parties’ Senate challenger primaries. Conclusions and Caveats In this paper I have limited my attention to comparing 2014 to previous election years with regard to competition and candidate fundraising. The data here show that there was some turmoil within the Republican Party in 2014, but that the extent to which that turmoil reflected any sort of “civil war” is ultimately in the eye of the beholder. In my analyses of primary competition over the 1970-2014 time period, it is clear that wave elections produce heightened primary conflict within the party that is riding the wave. Such competition, furthermore, does 7 not immediately subside once that wave has passed (refer back to Figure 5 for a display of this). Democrats experienced a large number of primary challenges in 1974, and many of these were ideological in nature. Several similar challenges took place within the party in 1976. Similarly, Republicans saw a large number of ideological challenges in 1994, and a smaller – but still atypically large – number in 1996. One can think of such challenges as instances of candidates trying to catch the wave before it has completely receded. The unusually large Republican wave in 2010 may well have produced similar effects – that is, we may simply be seeing the ebbing of the 2010 tide. If this is the case, ideological challenges can be expected to diminish in the upcoming years. The success Republican incumbents had in repelling so many of this year’s challengers (and any accompanying media narrative suggesting that the establishment “won the war”) may well contribute to this. I have said little here about incumbents’ activities during the primaries. As we detail in our forthcoming analysis of independent expenditures in the 2014 primaries, there was far more outside spending on behalf of incumbents in 2014 than in any previous election. It is possible to look at the crop of primary challengers that emerged in 2014 and conclude that they were somehow lacking – that few of them had the ability to nationalize their campaigns in the manner that previous challengers such as Richard Mourdock or Ned Lamont in the Senate, or Andrew Harris or Donna Edwards in the House, had done. This may in fact be the case; some media coverage in 2014 did focus on the flaws of some of the more prominent Senate primary challengers. Yet incumbents clearly played a role in making this the case. Preemptive spending by incumbents such as Lindsey Graham, Lamar Alexander, and John Cornyn (and by allied Super PACs) may have insulated these incumbents from serious threats, may have deterred outside groups from spending money against them. In short, there is some evidence that incumbents took the threat of primaries seriously in 2014, but there is no way to demonstrate the consequences of efforts to preempt competition. More broadly, the role of Super PACs and other independent expenditure groups in 2014 merits consideration, and this is the theme of the accompanying slides by Michael J. Malbin.5 Independent expenditures in 2014 were higher than was the case in 2010 or 2012, and this increase was largely the consequence of spending by recently-formed Super PACs. Since I have confined this paper to an analysis of primary candidates, however, I will merely make two points about the interaction between independent expenditures and candidate fundraising. First, the Super PAC spending on behalf of incumbents is unusual. In 2010 and 2012, the candidates who drew the most outside spending were either open seat races (for instance, Ted Cruz and David Dewhurst race in Texas) or challengers to incumbents such as Arkansas’ Bill Halter or Indiana’s Richard Mourdock. Although by 2012 it had become de rigeur for presidential contenders to be supported by Super PACs, it was uncommon until 2014 for candidate-specific Super PACs to support congressional incumbents in their primaries, and it was similarly rare for incumbents to be supported by any independent spending at all. This clearly changed in 2014. Second, recall the discussion above of the lack of “nationalization” among the 2014 primary challenges. Although spending in support of incumbents increased in 2014, there also was a substantial increase in the amount of independent spending in support of primary challengers or in opposition to vulnerable incumbents. Has independent spending reduced the need for candidates or groups to appeal to a nationwide base of ideologically motivated donors? 8 Many of the groups that engaged in independent expenditures do not have the capability to bundle contributions or mount aggressive online campaigns. And even the groups that do, such as the Club for Growth, may simply find it easier to make independent expenditures. This is a development that is worth watching in coming elections. Do this year’s primaries suggest anything about the primary system? There has been a noticeable increase in talk of primary reform, as epitomized by California’s adoption of a nonpartisan top-two primary. There is little consensus on what might be done, and thus far the results in California do not suggest that changes in primary laws will have a profound effect on the conduct of primary campaigns. Furthermore, as I have argued elsewhere, there is some evidence that changes to primary laws can deter fringe candidates but there is little evidence that they will affect the sorts of more consequential challenges considered here. In many ways, there was less, rather than more, turmoil in the 2014 primaries than in the past two elections, and it is likely that within a few years we will be lamenting the lack of competitiveness in primaries rather than discussing threats to the parties. And to the extent that we have seen enduring changes in congressional primaries, the culprit may well be the changed campaign finance system, and not the primaries themselves. 9 Figure 1: Number of Competitive Primary Challengers by Year, 1970-2014 Note: Incumbent vs. incumbent primaries excluded. 10 Figure 2: Primary and General Election Competition Compared, 1970-2014 Note: Incumbent vs. incumbent primaries excluded. Primary challenges here as defined in Figure 1 – challenges where the incumbent is held to less than 75 percent of the vote. 11 Figure 3: Number of Defeated House and Senate Incumbents, 1946-2014 Note: This graph does include incumbent vs. incumbent primaries. 12 Figure 4: Number of Ideological House Primary Challenges, 1970-2014 Note: Incumbent vs. incumbent primaries excluded. 13 Figure 5: Comparing the Role of Ideology in Democratic and Republican House Primary Challenges, 1970-2014 Democrats Republicans Note: Incumbent vs. incumbent primaries excluded. 14 Figure 6: Total Contributions, Total Contributions Under $250, and Total Itemized Out-of-State Contributions to Primary Challengers, 1980-2014 Note: Incumbent vs. incumbent primaries excluded. 15 Figure 7: Out-of-State Contributions to House Primary Challengers Top Twenty Candidates, 2004-2012 Democrats 2014 Republicans 2014 16 Figure 8: Competition in House Open Seat and Challenger Primaries, 1970-2014, by Party Note: See text for a discussion of the fractionalization index. 17 Figure 9: Out-of-state Contributions and Small Contributions to Senate Primary Challengers, 2014 Note: Small contributions include unitemized contributions and itemized contributions of $250 or less. 18 Figure 10: Competition in Senate Open Seat and Challenger Primaries, 1970-2014, by Party 19 1 These are the two measures of competitiveness I use in both of my books. The 60 percent threshold is the most common threshold for determining general election competition. The 75 percent threshold is presented as a means of providing an expansive view of competitiveness while eliminating candidates who did not actively campaign, and of eliminating variation in such candidacies that results from differences across states in ballot access requirements. This expanded threshold also provides a full picture of election financing. Almost all races where incumbents are held to 75 percent or less feature at least one challenger who has raised enough to file with the Federal Election Commission, while virtually no races where the incumbent received more than 75 percent have any such candidates. 2 While it is clear that there has been an increase in ideological challenges, I caution that the precise measure of the number of ideological challenges may be affected by changes in coding procedure. For elections from 1970 through 2012, I rely on two reasonably objective expert sources, Congressional Quarterly’s Politics in America and the National Journal’s Almanac of American Politics. These are used in part because they are generally considered by political insiders to be nonpartisan sources of information on elections, and also as a means of establishing continuity in coding from one election to the next. Because these two books are not published until approximately a year after the election, I could not use them for this analysis of 2014. Instead, I draw heavily upon the analyses presented in the Cook Political Report and the Rothenberg Report, which are also considered to be nonpartisan but which may differ in that they provide more information on races than my sources in previous years. There may thus be a bias in favor of identifying a reason for the challenge; for the 1970-2012, thirty percent of challenges could not be categorized. In 2014, only four challenges, or 6.7 percent, were uncategorizible. It is thus possible that the number of ideological challenges was higher in previous years than the figures I provide, and some other analyses, such as Jeff Berry and Sarah Sobieraj’s The Outrage Industry (Oxford, 2013) have argued that this was the case in 2010 and 2012. In future work I will recode using the sources I used for prior years. 3 In Getting Primaried (pp. 81-86) I show this to be the case for many Republican challenges between 2002 and 2010. 4 The fractionalization index is a measure of competition that takes into account both the number of candidates and their vote share. I provide a discussion of the development of this index and some prominent books and articles that use it in Congressional Primary Elections, pp. 124-26. The index is operationalized as F = 1 - ∑ [(C1)2 + (C2)2+ (C3)2+ (C4)2. . .] Where F is the fractionalization index, C1 is the percentage of the total vote received by the first candidate, C2 is the percentage of the total vote received by the second candidate, and so on. This yields an index where a one-candidate race has a fractionalization index of zero and a race where two candidates split the vote would have a fractionalization index of 0.5 (or 1 – (0.52 + 0.52)). The larger the number of similarly competitive candidates, the closer the index is to 1. For instance, a race with ten candidates who received ten percent of the vote each would have an index of 1 – [(.1)2 * 10], or 0.9. 5 See Michael J. Malbin, “Independent Spending in the 2014 Congressional Primaries.” Available at the Campaign Finance Institute website, www.cfinst.org. 20