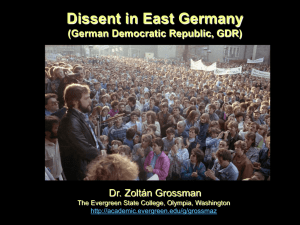

Let Bygones be Bygones? Socialist Regimes and Personalities in

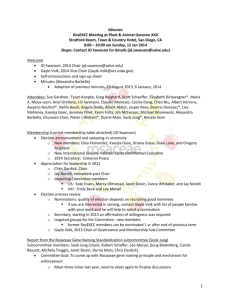

advertisement