BEFORE THE PENNSYLVANIA INSURANCE

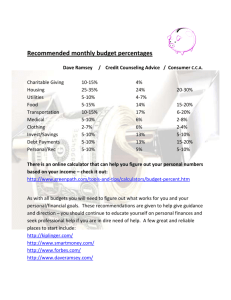

advertisement