Assessment and Instruction in Phonological Awareness

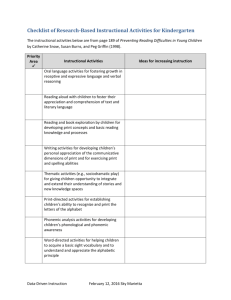

advertisement