This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached

copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research

and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution

and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or

licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the

article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or

institutional repository. Authors requiring further information

regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are

encouraged to visit:

http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

Author's personal copy

International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Business Review

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ibusrev

Regional integration and the international strategies of large

European firms

Chang Hoon Oh a,*, Alan M. Rugman b,1

a

b

Faculty of Business, Brock University, 500 Glenridge Avenue, St. Catharines, Ontario, L2S3A1, Canada

School of Management, Henley Business School, University of Reading, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon, RG9 3AU, United Kingdom

A R T I C L E I N F O

A B S T R A C T

Article history:

Received 17 June 2010

Received in revised form 18 April 2011

Accepted 30 May 2011

From the perspective of regional economic integration we decompose international

strategy into regional integration strategy and three types of global strategy (global sales,

global production, and pure global integration). Using 1100 firm-year observations we find

that 60% of the largest European firms pursue a regional integration strategy. We also find

that global strategies vary. We examine the firm specific factors that affect global

strategies. In general, R&D capability determines a global production strategy, whereas

firm size and managerial capability determine both a global sales strategy and a pure

global integration strategy.

Crown Copyright ß 2011 Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

European firms

Multinational enterprises

Regional integration

Regional versus global strategy

1. Introduction

Today an unresolved issue is whether large firms can pursue a ‘global’ or a regional strategy. By global we mean an

extension of home country domestic strategy to a global context, assuming that the world is flat such that there is

homogeneity in production and consumption patterns. By regional we mean sales or asset dispersion within each of the

broad triad regions of the E.U., North America and Asia. Today firms are required to report their sales and assets across these

broad geographic regions.

A great deal of ambiguity and misunderstanding remains in the literature as to when and how a global strategy can be

used (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1991; Zou & Cavusgil, 1996). The literature on global strategy recognizes some of the complexities

of globalization and of global strategy itself but it also generates confusion about when to use it. In addition there is now

ambiguity in the empirical support for global strategy, especially in light of recent finding that regional strategy is now being

used by many large firms (Rugman & Verbeke, 2004, 2005). In this paper we provide new empirical work which helps us test

the relative importance of global and regional strategies across large European firms. To facilitate this we first develop a new

framework combining the firm-specific and country-specific factors that determine global or regional strategy.

The early literature of global strategy is a simple extension of domestic competitive strategy. Hout, Porter, and Rudden

(1982) suggest using a portfolio approach in order to leverage a competitive edge in different countries to achieve a synergy

effect across different products and markets. Levitt (1983) proposes that the best global strategy is to standardize a product

for a global market in order to produce a high quality product at a low cost. Hamel and Prahalad (1985) argue that global

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 905 688 5550x5592; fax: +1 905 378 5716.

E-mail addresses: coh@brocku.ca (C.H. Oh), a.rugman@henley.reading.ac.uk (A.M. Rugman).

1

Tel.: +44 (0)1491 418 801.

0969-5931/$ – see front matter . Crown Copyright ß 2011 Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2011.05.009

Author's personal copy

494

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

strategy requires product varieties by sharing core competencies in proprietary assets across product lines. A large related

literature emphasizes strategic flexibility in order to gain a comparative advantage (Kogut, 1985) and coordinate

independence across countries (Porter, 1986). On the other hand, Bartlett and Ghoshal (1989) suggest a transnational

solution that focuses on balancing pressures for integration and responsiveness. In addition, Ohmae (1985) and Yip (1989)

focus on how industry and external environments drive globalization. Kobrin (1991) gives special attention to intra-firm

resource sharing and learning across borders within a firm’s network.

Recent studies on the nature of regional strategies question the existence of global strategy itself in both theory and

practice (Ghemawat, 2007; Rugman & Verbeke, 2004). The empirical evidence suggests that globalization is not uniform

across economic space due to the segmentation of manufacturing process carried out in different locations (Rugman, 2005).

Therefore, the strategies of multinational enterprises (MNEs), which are embedded in the causes and consequences of

globalization, may not be uniform (Buckley & Ghauri, 2004). In summary, the new regional literature demonstrates that the

world’s largest MNEs operate regionally (Rugman, 2005; Rugman & Verbeke, 2004) or semi-globally (Ghemawat, 2001,

2007) rather than globally. Small and medium size MNEs also show a regional orientation (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009; Lopez,

Kundu, & Ciravegna, 2009). This recent evidence suggests that new empirical work linking economic integration with the

strategies of MNEs needs to decompose integration into regional integration and global integration.

A related problem is that the existing literature does not tell us what motivates a firm’s global (or regional) strategy.

Several determinants could be the driving force for such a strategy, including firm size (Levitt, 1983), proprietary assets as

core competencies (Hamel & Prahalad, 1985), managerial skills for coordination and integration (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989;

Kogut, 1985; Porter, 1986) and external factors (Ohmae, 1985; Yip, 1989). Future research needs to focus on whether these or

different drivers exist in regard to using global or region strategies. We can address these questions by classifying strategies

into two broad building blocs, firm specific advantages (FSAs) and country specific advantages (CSAs). This classification will

help us test the determinants of global and regional strategies.

Here we will compare the extent of the regional integration of Europe’s largest firms to three types of global integration,

namely global production (integrating upstream activity globally), global sales (integrating downstream activity globally)

and pure global integration (integrating both upstream and downstream activities globally). We empirically test the

consequences of globalization (or regionalization) based on the extent of an MNE’s international sales and assets.

Using regional integration as a reference strategy, it is found that MNEs choose a global production strategy when they

possess FSAs in R&D; they choose a global sales strategy when they have FSAs in growth orientation and in firm size and

managerial capability; and they choose a pure global integration strategy when they have FSAs in firm size and managerial

capability. However, the majority of large MNEs pursue a home region integration strategy. We also find that home CSAs

determine which strategy is used.

The rest of the paper is organized into four sections. In Section 2 we examine the international and regional activity of

large European MNEs and categorize them into four types of international strategy based on the perspective of economic

integration. In Section 3 we discuss our data and methodology. In Section 4, we present empirical results from a multinomial

logit regression analysis that we use to find the firm-level and country-level factors leading to global or regional integration

strategies. Finally we conclude with a discussion of future research issues in Section 5.

2. Theory and evidence of regional integration and MNE strategy

2.1. Regional integration

Regional integration has been an integral part of the international economic system since the 1960s. As of 2008,

more than 230 regional or bilateral trade agreements and about 1950 bilateral investment treaties exist worldwide. In

addition, several regional trade agreements have expanded their membership and economic size over time, which has

affected the activities of MNEs (Fratianni & Oh, 2009; Oxelheim & Ghauri, 2004). More than 50% of world trade and 40%

of foreign direct investment (FDI) are generated from within a firm’s home region triad (North America, Europe and

Asia-Pacific). In fact, regional integration, or so-called new regionalism, has gone beyond preferential tariff reduction

toward deeper integration, and FDI is now as much a central part of new regionalism as trade was in old regionalism

(Ethier, 2001). Thus, macro economic and institutional factors provide favorable environments for MNEs that operate

within their home region. Several studies have used a gravity equation modeling in their country-level analysis (e.g.,

Brenton, Di Mauro, & Lücke, 1999; Fratianni & Oh, 2009; Hejazi, 2009) and shown that regional integration leads to

regional bias in both trade and FDI.

Applying the gravity concept to MNEs, Ghemawat (2001) suggests that firms should analyze not only opportunities in

foreign countries, but also the costs and risks that arise from operations in these countries. These costs and risks arise from

the four dimensions of distance: cultural, administrative/political, geographic and economic. However, Ghemawat’s

dimensions are to be used for an industry- and country-level analysis rather than a firm-level analysis.

At the firm level, Kobrin (1991) suggests that the greater the intra-firm resource flows, the greater is the level of

transnational (global) integration. However, this simple type of globalization has been re-evaluated and challenged due to

the asymmetry existing in CSAs and the complexity of economic (regional) integration, as the benefits of FSAs and CSAs are

likely enhanced by geographical proximity (Buckley & Ghauri, 2004). Thus deeper economic integration may increase intraand inter-firm resource flows within an economic cluster or a regional bloc.

Author's personal copy

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

495

From a micro-perspective, Morrison, Ricks, and Roth (1992) argue that implementing a global strategy is often costly

because of internal resentment and resistance and the high opportunity costs in developing key subsidiary strengths. As a

result, both headquarters and subsidiaries prefer a regional strategy because it is a safer and more manageable alternative to

a global strategy. They suggest that regionalization offers an opportunity for organizational change, which builds upon the

distinctive competencies of the entire organization, and, at the same time, allows the organization to respond to legitimate

pressure from greater integration.

Transaction cost economics theory implies that MNEs can better align their FSAs and CSAs in their home region than in

the foreign region. By expanding within its home region, an MNE can lower its adaptation costs while improving its

international experience through the redeployment of its core FSAs in knowledge in less risky locations (Rugman & Verbeke,

2005). In short, CSAs in regional coherence, such as economic integration and political harmonization, can reduce the

adaptation costs of MNEs within their home region of the triad.

Building on the nature of regional integration at the CSA level, as outlined above, and moving to using firm-level data on

FSAs, Rugman (2005) shows new evidence for regional integration at the firm-level. In his analysis only a few firms operate

globally, and more than 80% of the 500 large firms operate regionally. Indeed, more than 70% of the sales of the large MNEs

occur in their home region markets. Subsequent studies show supporting evidence for regional MNE perspectives from all

angles of an industry, a country and a region (e.g., Collinson & Rugman, 2008; Grosse, 2005; Lopez et al., 2009).

We extend Rugman’s (2005) single year analysis of 2001 to eight years, 2000–2007, and focus on the 219 largest European

MNEs. While there were 249 European firms listed in the Fortune Global 500 between 2000 and 2007, thirty of the firms did

not provide any information about their geographic sales or assets.

Table 1 shows the international and regional presence in regard to sales and assets of these European MNEs. In the first

two columns of the table, we use conventional scale measures of internationalization to measure the geographic tendencies

of large European MNEs: foreign-to-total sales (FSTS) and foreign-to-total assets (FATA). The results show that large

European MNEs generate approximately 50% of their sales (the first column) and their assets (the second column) outside of

their home country. These values are consistent throughout the sample period. Therefore, it can be assumed that large

European MNEs are certainly internationalized. The important implication of the first two columns is that the strategic

importance of the international market is about the same as that of the domestic market. The results show that the foreign

sales and assets of the sample firms are very stable, and that their internationalization trend is very slow. The FSTS only

increases by 2% on average, while the FATA remains the same.

The next two columns of Table 1 show the intra-regional sales (the third column of Table 1) and assets (the fourth column

of Table 1). The intra-regional sales-to-total sales (IRSTS) is a firm’s sales in Europe divided by its total sales, while the intraregional assets-to-total assets (IRATA) is a firm’s assets in Europe divided by its total assets. IRSTS and IRATA include

domestic sales and assets, respectively. Clearly the domestic market is a key component of regional integration. As a firm’s

capabilities are usually developed in its headquarters and home country (Doz, Santos, & Williamson, 2002; Hennart, 2007),

the domestic sales and assets need to be included to conduct a proper analysis of the firm’s strategy. For example, scale

benefits and brand equity depend on domestic, as well as international, sales and assets.

The results show that large European MNEs have more than 70% of their sales and assets located in Europe. The results do

not show any evidence of globalization; instead they show a regionalization trend. The IRSTS and IRATA increased by 2% and

6% on average, respectively, from 2000 to 2007. As both the FSTS and IRSTS increased by 2% in the eight years studied, the

large European MNEs increased their international sales, but only within Europe during the period. While the FATA remains

the same, the IRATA increases by 6% during the eight years studied. This result indicates that the large European MNEs

expand on an intra-regional basis.

In sum, regional economic integration provides a favorable environment within which MNEs can operate. Firm-level

evidence also shows that most European MNEs operate mainly within Europe. However, some firms extend their operations

Table 1

International and regional presence of large European MNEs: 2000–2007.

Year

Multinationality (foreign-to-total; %)

Regional activity (intra-region-to-total; %)

Sales (FSTS)

Assets (FATA)

Sales (IRSTS)

Assets (IRATA)

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

51.2

50.6

50.8

49.9

49.7

50.6

52.8

53.9

48.6

50.5

51.7

50.0

47.8

46.5

47.4

48.7

68.3

68.9

69.6

70.6

71.1

70.8

69.8

70.7

68.5

69.2

71.0

72.1

74.1

73.5

74.3

74.5

Average

51.2

48.7

70.1

72.51

Source: Authors’ calculations based on annual reports. Data include only firms that report all four measures in a year. Information for 219 firms is used, but

observations vary by year and by measures.

FSTS is foreign-to-total sales; FATA is foreign-to-total assets; and IRSTS is intra-regional sales-to-total sales; and IRATA is intra-regional assets-to-total

assets.

Author's personal copy

496

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

outside Europe. In the next sections, we will closely analyze why MNEs choose different international strategies and what

determines these choices.

2.2. Four types of international strategy

Much discussion exists in regard to the literature on simple global strategy. A conventional global strategy does not

distinguish characteristics of foreign countries (e.g., Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989; Hout et al., 1982), but, rather, implicitly

addresses the advantages of regional strategies. For example, Ohmae (1985) describes the difficulties faced by even the

largest firms to imitate their home region (domestic) strategy in other triad markets. Thus a simple extension of Western

business strategy does not work well in the Asia Pacific region (Lasserre, 1996). Buckley and Ghauri (2004) underline the

size-of-country benefit for MNEs in regard to regional economic integration. Yamin and Forsgren (2006) note that MNEs

suffer a greater degree of severity in regard to control problems outside of the home region and, therefore, focus on home

region markets rather than global markets. Rugman and Verbeke (2005) and Ghemawat (2007) explain that an MNE’s costs

and inefficiencies increase outside of the home region, and, thus, its activities are bounded by its geographic presence.

Bartlett and Ghoshal (1989) define three types of firm strategy in regard to geographic expansion. They use somewhat

unfortunate terms for these three types of strategies. First, ‘international’ firms build a competitive advantage through

knowledge transfer across borders and subsequent production in host country subsidiaries. Second, ‘global’ firms engage in

the worldwide export of their goods, and are supported by downstream-oriented subsidiaries abroad. Third, ‘multinational’

firms derive their strength from firm-specific capabilities embedded in their subsidiaries. Here multinational firms are very

nationally responsive in the various countries in which they operate.

However, in reality, MNEs integrate their upstream and downstream operations in their home region due to regional

economic integration and their region-bound FSAs as discussed in the previous section (Section 2.1). The MNEs are likely to

efficiently reduce their liability of foreignness and coordination costs in intra-regional activities by operationalizing their

FSAs and minimizing country-specific differences, such as cultural, geographic and institutional distances. Thus, MNEs

efficiently integrate their upstream and downstream activities within their home region and their domestic country acts as a

hub for their regional integration network. In the home region, dividing an MNE’s strategy into multinational, international,

and global strategies does not help our understanding of the geographic strategy of an MNE. Likewise, Buckley and Ghauri

(2004) note that horizontal FDI in an integrated market complements vertical FDI in other non-integrated markets. Indeed,

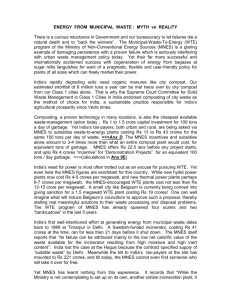

most MNEs use a regional integration strategy that corresponds to Quadrant 1 in Fig. 1.

When discussing an MNE’s activities outside of its home region, we can modify Bartlett and Ghoshal’s three types of firms

from the perspective of regional integration. First, an MNE manufactures the majority of its products in a foreign region due

to high CSAs, such as labor costs, human capital, natural resources and technology. Although some of the products sell in the

foreign region in which they are produced, the majority of the products sell in the MNE’s home region through intra-firm

Fig. 1. Regional integration and international strategies.

Author's personal copy

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

497

trade channels (from the foreign region to the home region). We call this type of strategy a global production strategy,

which corresponds to Quadrant 2 in Fig. 1. Thus, the upstream activity of the MNE is global, but its downstream activity is

regional.

Next, an MNE manufactures its products through its regional supply chains, but the products are exported (using both

intra- and inter-firm methods) to foreign regions. Three reasons exist for using this type of strategy. First, an MNE

manufactures its products in a regional cluster but sells them worldwide in order to achieve economies of scale and scope.

Second, industry and product lifecycles lead the MNE to export its products to a foreign region as the home region market is

already mature, but the MNE still has an excess production capacity or inventory. Third, an MNE’s knowledge and production

knowhow are too complex to transfer to its foreign region subsidiaries where the human capital is limited. We call this type

of strategy a global sales strategy, which corresponds to Quadrant 3 in Fig. 1. Thus, the downstream activity of the MNE is

global, but its upstream activity is regional.

Finally, an MNE develops its own capabilities in each foreign region. If it is a European MNE, then it will develop its

subsidiary-specific capabilities in North America and Asia-Pacific separately. The MNE improves its regional responsiveness,

so that most of its activities can stay within a foreign region (i.e., produce and sell in the same region). The MNE can integrate

and coordinate these capabilities through its regional headquarters, and some, but not many, of the activities may interact

inter-regionally. We call this type of strategy a pure global integration, which coincides with Quadrant 4 in Fig. 1.

Our four types of international strategy also refine Porter’s industry-level international strategy at the firm-level. Porter

(1986) divides international strategy into multidomestic industry and global industry. He explains multidomestic industry

as ‘‘industries in which competition in each country (or small group of countries) is essentially independent of competition in

other countries’’ (p. 11). However, except for a few industries in countries that are perfectly protected by the national

government, no such independent industry exists due to economic integration. Thus, we replace the impractical

multidomestic strategy with a regional integration strategy.

2.3. Determinants of international strategies

Global integration is much more difficult and rare in today’s business practices than regional integration. MNEs face a

more diverse and greater number of competitors when they integrate their upstream and downstream activities globally

than when they operate regionally or domestically (Porter, 1986; Rugman, 2005). However, some FSAs and CSAs may

improve the configuration and coordination of MNEs’ global activities and position them on a global basis rather than on a

home-region basis.

The literature has identified the FSAs (or resources) that lead a firm to engage in global activities. Firm size is the first FSA,

which is a proxy for economies of scale (Levitt, 1983). In addition, a large firm presents a greater threat to potential

competitors, and, thus, the large firm finds that an aggressive integration strategy is more attractive than a cooperation

strategy (Shan & Hamilton, 1991). Thus, firm size associates positively with global integration strategies.

Managerial capability in a Penrose sense is another FSA, as it improves a firm’s efficiency of integration and coordination

of different functions across various geographic markets (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989, 1991). Managerial capability enables the

firm to manage strategic changes and interdependencies (Doz & Prahalad, 1988) and directly relates to the global operation

(Roth & Morrison, 1992). Therefore, we expect that managerial capability will be positively associated with the global

integration strategies.

R&D and marketing capabilities are intangible aspects of a firm’s assets that create a competitive edge and generate

monopolistic rents (Caves, 1971; Hamel & Prahalad, 1985; Porter, 1986). These intangible assets encourage the firm to

diversify its business lines and geographic markets (Chang, 1995). MNEs can also maximize their internalization benefits

through internalizing their technology and marketing resources (Hennart, 1982; Rugman, 1981). Thus, firms that have better

R&D and marketing capabilities choose global integration strategies rather than regional integration strategy.

In addition, a firm’s financial capability may allow it to enter into foreign markets and lead to long term success as

financial health provides a great range of feasible investment opportunity for the firm at a lower cost of funding in new

geographic markets (Agarwal & Ramaswami, 1992; Grosse, 1992). Therefore, financial capability positively determines

global integration strategies.

Finally, growth orientation is likely to be another motivation for firms looking expansion to foreign markets due to the

limited size of domestic and home region markets (Cavusgil, 1984). In addition, a firm seeking a growth opportunity needs to

expand into different foreign markets in order to hedge its customer-side risks but also its production-side risks because the

firm faces international product and industry life cycles (Vachani, 1991; Vernon, 1966). We expect that growth orientation

will positively determine global integration strategies rather than a regional integration strategy.

These FSAs positively affect global integration as they will turn out to be internalization benefits when firms transfer

them across borders (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Rugman, 1981; Shan & Hamilton, 1991; Teece, 1986). However, some FSAs are

not easily transmitted to foreign countries (Stuckey, 1983) or foreign regions (Rugman & Verbeke, 2005) due to their

complexity and regional differences. In a foreign region, even large MNEs suffer from the incremental costs associated with

coordinating and integrating country-level (and region-level) differences, transferring FSAs to foreign region subsidiaries

and developing subsidiary specific capabilities (Morrison et al., 1992). Thus, incremental complexities and differences will

generate an organizational boundary when an MNE transfers its FSAs from its home region to a foreign region. In particular,

we expect that these FSAs will have an asymmetrical effect between upstream (production) integration and downstream

Author's personal copy

498

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

(sales) integration. While we expect that strong FSAs will be positively associated with global strategies, the level of

boundary and asymmetric effect of each FSA will need to be analyzed empirically.

Regarding CSAs, domestic and regional characteristics also determine a firm’s internationalization strategy (Porter, 1990;

Rugman & D’Cruz, 1993; Wan & Hoskisson, 2003). CSAs are not usually transferable to other countries, and therefore strong

CSAs in the domestic and integrated regional market may make MNEs focus more on their domestic and integrated regional

markets. If a CSA is a downstream advantage (i.e., domestic market size), then the MNE will not likely use a global sales

strategy. Likewise if a CSA is an upstream advantage (i.e., unemployment rate, literacy rate, and quality of infrastructure),

then the MNE will not likely use a global production strategy. In other words, strong domestic CSAs will provide an MNE with

a favorable environment for implementing a regional strategy, and, therefore, a positive relationship is expected to exist

between strong domestic CSAs and regional strategy.

On the other hand, strong domestic CSAs offer MNEs competitive advantages not only in the domestic and regional

market, but also in global markets where MNEs compete with foreign MNEs (Porter, 1990). In other words, domestic and

regional growth would complement, not be a substitute for, global growth (e.g., Autio, Sapienza, & Almeida, 2000) because

favorable domestic and regional CSAs provide experiential learning experience in the process of global integration

(Contractor, 2007; Rugman & Oh, 2010). Therefore, we expect that strong domestic CSAs will be positively related to global

strategies. Hence, theories suggest that the effects of CSAs can either be positive or negative, and, as such, the relative

strength of each CSA will be empirical question to analyze. We include the above four CSAs as control variables.

3. Data and method

3.1. Data

We select 249 large European MNEs, as listed in the Fortune Global 500, between 2000 and 2007. The 249 MNEs originate

from 19 European countries: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the

Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and the United Kingdom. Sixty percent of

the MNEs are from three countries: France, Germany and the United Kingdom. The list of MNEs used is available upon

request. As discussed above (Section 2.1), 30 of 249 MNEs do not provide information about their geographic sales and assets.

Regarding the measure of the degree of integration, Kobrin (1991) measures the degree of integration at the aggregated

industry level using a single indicator of intra-firm sales. We use both the sales and assets data in order to divide the

upstream and downstream integration at the firm level. Thus, we use two scale measures: IRSTS (i.e., intra-regional sales-tototal sales) and IRATA (i.e., intra-regional assets-to-total assets). The sales and assets data were hand-collected from the

annual reports of each firm and supplemented by the OSIRIS of Bureau van Dijk. Both the IRSTS and IRATA represent the

degree of regionalization (or globalization) for the downstream (IRSTS) and upstream (IRATA) sides of value chains.

Data on these six FSAs are gathered from the OSIRIS and COMPUSTAT Global databases and supplemented by data from

the annual reports of each firm. Firm size, which is a proxy of economies of scale, is measured using the log of the firm’s sales.

Managerial capability is measured using Tobin’s Q (Sudarsanam & Mahate, 2006). R&D and marketing capabilities are

measured using R&D expenditures and advertising and selling expenses divided by total sales, respectively (Chang, 1995;

Kim & Lyn, 1990). Financial capability is measured using the book value of assets divided by debt (Myers & Majluf, 1984; Oh

& Oetzel, 2011). Growth orientation is measured using the firm’s five-year compounding sales growth rate (Kim & Lyn, 1990).

In order to reduce the issue of reverse causality, we use one year lagged values for the FSAs in the model.

The World Development Indicator (2009) by the World Bank is the source of the country characteristic variables:

domestic market size, which is measured using the log of the GDP; unemployment rate; adult literacy rate; and

infrastructure quality, which is measured using the total number of land-line telephones and mobile phone subscriptions per

1000 persons. These measures are widely accepted conventional measures for the quality of country characteristics (see, for

example, Canning, 1998; Oh & Oetzel, 2011; Yeniyurt & Townsend, 2003). In our sample, the European MNEs share the same

home region characteristics, and, therefore, we do not control for regional characteristics. All of the monetary variables are

expressed in real terms of U.S. dollars.

3.2. Model

As our dependent variable is a categorical variable, a multinomial logit regression model is used to estimate the effects of

the firm- and country-specific characteristics on the logarithm of the probability that each of the four qualitative alternatives

(i.e., regional integration, global production, global sales and global integration strategies) would be selected. The

multinomial logit model provides three parameter estimates for each independent variable, one for ‘global production’,

another for ‘global sales’, and the other for ‘global integration’. The parameter estimates are measured against the reference

strategy that is ‘regional integration’. The coefficients are estimated with the assumption that the sum of the probabilities of

each of the four strategies being chosen is equal to one.

We control for the industry-fixed effects in order to capture the unobserved industry characteristics that are likely to

influence the propensity of global and regional integration (Rugman & Oh, 2007) and the level of the international supply

chain linkages (Giroud & Mirza, 2006). We also use White’s heteroskedasticity-robust standard error method in order to

reduce the possible presence of heteroskedasticity. We check the robustness of our findings in multiple ways, which will be

Author's personal copy

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

499

discussed later. A multinomial logit model has been previously used in international business literature to estimate the entry

mode decision (Anand & Delios, 1997; Chen & Hu, 2002; Kogut & Singh, 1988), location choice decision (Strange, Filatotchev,

Lien, & Piesse, 2009) and types of internationalization strategy (Hollenstein, 2005).

4. Empirical results

4.1. Categorization of international strategy

Among the 219 firms in Table 1, 187 firms have information for both the IRSTS and IRATA. However, some of the firms do

not provide information for the entire eight years. Finally, we gather 1100 firm-year observations, which allow us to further

analyze the MNE’s international strategies.

In Fig. 2, we place each of the European MNEs in one of the four quadrants discussed in the previous section (Section 2.2).

We use a 60% threshold for both the IRSTS and IRATA in order to divide the international strategy into a regional integration

strategy and three global integration strategies. Rugman and Verbeke (2004) use a 50% threshold for the IRSTS only. Although

this classification scheme is, in general, robust for the sales data, Osegowitsch and Sammartino (2008) argue that a 50%

threshold could be too strong and overstate regional firms. In addition, the IRATA is usually higher than the IRSTS. Therefore,

we relax the 50% threshold and use the 60% threshold for this study. Due to limited space in Fig. 2, we do not list all of the

MNEs in each quadrant. The definitions adopted in Fig. 2 are as follows:

(1) Regional integration (Quadrant 1): European MNEs that have more than 60% of their sales and assets in Europe (or less

than 40% of their sales and assets outside Europe). 60% of large European MNEs were located in Quadrant 1.

Intr a -Re gion a l Sa le s

1. Regional Integration

3. Global Sales

Intra-Regional Assets

Intra-regional sales < 60%

Intra-regional assets ≥ 60%

Intra-regional sales ≥ 60%

Intra-regional assets ≥ 60%

129/1100 (12%)

Examples:

A.P. Møller-Mærsk Group; ABB;

ABN AMRO Holding; Akzo Noble; AREVA;

Cie Nationale à Portefeuille;

ING Group; L.M. Ericsson; LVMH;

Novartis; Prudential (UK); Econik;

Wolseley; etc.

664/1100 (60%)

Examples:

Altadis; Arcandor; Assicuazioni Generali;

Aviva; Bertelsmann; Bouygues; BT;

Carrefour; Cepsa; Commerzbank; Corus;

Deutsche Telekom; Électricité de France;

E.ON; ENI; Fiat; Finmeccanica; Fortum;

GasTerra; Groupo Ferrovial; Ladbrokes;

Lagardère; Lufthansa; Man Group; PPR;

Saint-Gobain; Svenska Cellulosa; Skanska;

Suez; Swiss Life; Tesco; Thales Group; TNT;

TUI; Vinci; Volkswagen; etc.

4. Global Integration

2. Global Production

Intra-regional sales < 60%

Intra-regional assets < 60%

250/1100 (23%)

Examples:

Alcatel-Lucent; Anglo American;

AstraZeneca; Sanofi-Aventis; BAE systems;

BP; Christian Dior; Compass Group; Delhaize;

Diageo; Electrolux; GlaxoSmithKline;

Hochtief; Holcim; HSBC; Invensys; Lafarge;

Linde Group; National Grid (UK); Nestlé;

Nokia;

Old Mutual; Roche Group; Royal Ahold;

Royal Dutch Shell; Schneider Electric;

Siemens; Unilever; SABMiller; etc.

Intra-regional sales ≥ 60%

Intra-regional assets < 60%

57/1100 (5%)

Examples:

Adecco; AXA; Barclays;

Continental (Germany); Heineken;

Henkel; Repsol YPF; Total; UBS;

Vivendi Universal; etc.

Note: The total number of observations is 1,100. Information for eight years is used for 187 firms.

Examples are based on the latest available information. Observations vary across year.

Fig. 2. Large European MNEs and international strategies.

Author's personal copy

500

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

(2) Global production (Quadrant 2): European MNEs that have more than 60% of their sales, but less than 60% of their assets

in Europe (or less than 40% of their sales, but more than 40% of their assets outside Europe). Only 5% of large European

MNEs are located in Quadrant 2.

(3) Global sales (Quadrant 3): European MNEs that have less than 60% of their sales, but more than 60% of their assets in

Europe (or more than 40% of their sales, but less than 40% of their assets outside Europe). About 12% of large European

MNEs are located in Quadrant 3.

(4) Global integration (Quadrant 4): European MNEs that have less than 60% of their sales and assets in Europe (or more than

40% of their sales and assets outside Europe). About 23% of large European MNEs are located in Quadrant 4.

Sixty percent of large European MNEs use a regional integration strategy as they have more than 60% of their sales and

assets in Europe. These MNEs actively integrate and coordinate their activities in their home region of Europe. Their home

region is the central area in which they create and foster their regional goods and services across several countries. Regional

economic integration offers the most substantial market size benefits to such MNEs (Buckley & Ghauri, 2004). The other

40% of the MNEs are categorized into global production (5%), global sales (12%) and global integration (23%) as shown in

Fig. 2.

Another important result shown in Fig. 2 is that European MNEs balance their upstream (assets) and downstream (sales)

activities in international markets. Eighty-three percent of the large European MNEs use either a regional or pure global

integration strategy. Although global offshore manufacturing and sourcing have received a large amount of attention from

the media and academics, the global production strategy is limited to 5% of the MNEs. The global sales strategy, which is the

strategy most likely to be used when exporting goods produced in the home region to foreign regions, is only used by about

12% of the MNEs. Therefore, an MNE’s organizational structure should balance assets and sales to coordinate and integrate its

operations regionally or globally.

We test the 60% threshold used in Fig. 2 in two ways. First, as is consistent with Rugman and Verbeke (2004), we change

the threshold from 60% to 50% and find consistent results. The 50% threshold is tauter than the 60% threshold as it requires

that more than 50% of the MNE’s sales or assets (instead of 40%) be categorized within one of three global strategies. The

threshold change categorizes 72% of the large European MNEs into regional integration, 4% into global production, 8% into

global sales and 16% into pure global integration.

Second, we relax the 60% threshold to 70%, which means that an MNE would need to have more than 30% of its sales and/

or assets in Europe. The relaxation re-categorizes 48% of the MNEs into regional integration, 6% into global production, 12%

into global sales and 34% into pure global integration. About 50% of the European MNEs use a regional integration strategy, so

the results are consistent.

Regarding the dynamics of the individual firms in Fig. 2, 55 firms (30% of the 187 firms) change their international

strategies between groups. There are also several firms which change more than once between groups. Thus, our measure of

international strategy has enough variation for useful analysis. In addition, only eight firms (4%) remain as purely domestic

companies during the observation period. Thus, the effects of pure domestic companies are very minor in our findings.

In the next section, we will examine the determinants of the four types of international strategies by using a multinomial

logit regression model.

4.2. Determinants of the four types of international strategies

Table 2 shows a summary of the statistics and correlation matrix of variables. This table does not show any symptoms of

collinearity. Due to the lagged variables and limited information of the FSA variables, the final sample consists of 599

observations.

The regression results of the multinomial logit regression model are in Table 3. The three columns explain the probability

of an MNE choosing a global production strategy (Column 1), global sales strategy (Column 2), or global integration strategy

(Column 3), respectively, against a regional integration strategy. The Pseudo-R Squared is about 0.44, which is equivalent to

about 0.8 of the linear regression (Hensher, Rose, & Greene, 2005, p. 339). The odds of success in correctly predicting four

alternatives are about 75% (in detail, 85% for regional integration; 60% for global sales; 68% for global production; and 72% for

pure global integration). Thus our model is well-specified and statistically sound.

Each FSA has a different impact on the three types of global strategy. Regarding global production, in the first column

of Table 3, R&D capability is positive and significant while managerial capability is significantly negative. An R&D

intensive MNE is likely to use an offshore production strategy in a foreign region and sell its products in the home

region. These MNEs have better technological knowledge, and, therefore, internalizing foreign technologies eventually

provides them FSAs in global production. An MNE with better managerial capability is less likely to choose a global

production strategy than a regional integration strategy. We presume that integrating both upstream and downstream

activities in the home region market requires more coordination capability than integrating only upstream activities in

the global market.

In the second column of Table 3, firm size, managerial capability and growth orientation are positive and significant,

while financial capability is significantly negative for a global sales strategy. An MNE having economies of scale and

managerial capability will choose the global sales strategy. It is likely that the MNE manufactures its products in the home

region and seeks foreign region markets to increase its economies of scale and scope. Therefore, serving several different

Author's personal copy

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

501

Table 2

Means, standard deviations and correlations.

Mean (S.D.)

Firm sizea

Managerial capabilitya

R&D Capabilitya

Marketing capabilitya

a

Financial capability

Growth orientationa

Domestic market size

Unemployment rate

Literacy

Infrastructure quality

9.901

(0.921)

0.426

(0.208)

0.024

(0.051)

0.414

(0.391)

4.510

(14.131)

0.168

(0.482)

27.4181

(0.910)

6.505

(2.419)

98.917

(0.637)

148.477

(17.030)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0.022

0.002

0.127

0.138

0.301

0.026

0.122

0.152

0.205

0.081

0.104

0.110

0.115

0.067

0.047

0.157

0.075

0.097

0.281

0.009

0.032

0.001

0.039

0.081

0.084

0.042

0.114

0.292

0.073

0.116

0.074

0.029

0.125

0.157

0.045

0.244

0.136

0.047

0.048

0.103

0.029

0.053

0.306

0.344

0.014

Note: N = 599.

a

Lagged one-year.

markets requires further coordination capability when compared to serving an integrated regional market. A fast growing

MNE will benefit from decreasing marginal costs in the short term by increasing its size even more. A lack of financial

resources may lead the MNE to choose global sales through an export platform likely because it cannot commit its assets to

both home and foreign regions. The literature on the exporting strategy finds similar results for firm-specific characteristics

(e.g., Cavusgil & Zou, 1994).

In the third column of Table 3, firm size and managerial capability are positively significant, while marketing capability is

negative and significant for a global integration strategy. As discussed in Section 2.3, economies of scale and coordination

Table 3

Determinants of regional and global strategies: multinomial logit regression. (i) 60% threshold of intra-regional sales and assets is used for categorizing

firms. (ii) Base model is Quadrant 1 (Regional integration).

Firm characteristics

Firm size (lagged)

Managerial capability (lagged)

R&D capability (lagged)

Marketing capability (lagged)

Financial capability (lagged)

Growth orientation (lagged)

Home country characteristics

Domestic market size

Unemployment rate

Literacy

Infrastructure quality

Successful prediction Rate

Number of observations

2 log likelihood

Pseudo-R Squared

Akaike Information Criterion

(1) Quadrant 2

Global Production

(2) Quadrant 3

Global Sales

(3) Quadrant 4

Global Integration

0.5576

(0.4636)

4.6076*

(2.5449)

65.2329**

(33.1277)

0.1953

(1.0173)

0.0114

(0.0873)

3.2909

(3.2765)

0.7887***

(0.2617)

8.4358***

(1.8060)

4.8851

(5.8085)

0.3897

(0.6731)

0.0215*

(0.0124)

0.5619*

(0.3293)

0.6667***

(0.1748)

3.6337***

(1.2631)

3.3243

(5.1933)

1.3437**

(0.5453)

0.0015

(0.0051)

0.106

(0.3544)

0.4567

(0.3838)

0.1973y

(0.1324)

1.7046y

(1.0466)

0.0778***

(0.0232)

0.0624

(0.2584)

0.7582***

(0.1324)

1.9305***

(0.4687)

0.0121

(0.0120)

0.5589**

(0.2201)

0.7679***

(0.0969)

0.1567

(0.2459)

0.0101

(0.0086)

75%

599

726.522

0.443

880.552

Note: * if p < 0.10, ** if p < 0.05; *** if p < 0.01. Two-tailed test. y if p < 0.10 at one-tailed test. Heteroskedasticity robust standard are in parentheses.

Industry-fixed effects and constant were estimated but not reported here.

Author's personal copy

502

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

capability are the most important characteristics of a globally integrated MNE. However, marketing capability may lead an

MNE toward regional integration instead of global integration. This result contradicts previous findings in the literature as a

global brand does not help an MNE to operate globally. We find that many leading prestigious brands, such as BMW, Ferrari,

Christian Dior, Gucci and Chanel, rarely manufacture their products outside of their home region. They do so in order to keep

their prestigious brand awareness and to protect their proprietary knowhow and technology from imitators. Therefore,

marketing intensive MNEs are likely to use a regional strategy in their production.

In summary, strong FSAs are generally positively associated with global strategies, but the asymmetric effect of each FSA

should be considered. R&D capability leads an MNE to choose a global production strategy; growth orientation leads an MNE

to expand its production activity globally; and firm size and managerial capability lead an MNE to expand its production and

sales activity globally. Marketing capability leads an MNE to integrate its sales and production activities regionally, but not

globally.

Regarding CSAs, some home country characteristics also have a different impact upon types of international strategy.

First, in production, a high literacy rate in the home country leads an MNE to expand outside its home region, while a high

unemployment rate and better infrastructure quality in the home country leads to an MNE focus on the home region (see

Column 1). Second, high unemployment and literacy rates in the home country lead an MNE to focus on sales in its regional

market (see Column 2). Third, a large domestic market size and a low unemployment rate push an MNE to integrate its

upstream and downstream activities globally rather than regionally (see Column 3).

The home country literacy rate affects the production side of global and regional integration decisions because

international knowledge transfers between home and host countries are likely higher when an MNE’s home nationals are

educated and sophisticated (Davidson & McFetridge, 1985). Due to the free movement of factors in an integrated market

such as the E.U., MNEs can benefit from lower labor costs (high unemployment rate) and better infrastructure in their

regional market. In addition, domestic and regional governments offer favorable incentives to attract investments within the

integrated region (Oxelheim & Ghauri, 2004). Large domestic market size (higher domestic demand) pushes MNEs to operate

globally. These MNEs likely build their global production chains in order to meet diverse domestic demand and also sell their

products (and surplus of domestic and regional markets) globally because their competitiveness over foreign competitors is

developed in the domestic markets.

4.3. Robustness checks

In Appendix A, we use a 70% threshold instead of a 60% threshold of IRSTS and IRATA, which we discussed in the previous

section (Section 4.1), as a robustness check. We use a 70% threshold because the mean values of the ITRSTS and IRATA are 70%

and 73%, respectively. The results are consistent with those found in Table 3: the R&D capability is positive and significant,

while the managerial capability is negative and significant for the global production strategy (Column 1); firm size and

managerial capability are positive and significant, while financial capability is negative and significant for the global sales

strategy (Column 2); and firm size and managerial capability are positive and significant, while marketing capability is

negative and significant for the pure global integration strategy (Column 3).

Second, we test the year-demeaned data in the multinomial logit model due to the panel structure of our data. We choose

to use a year-demeaned data analysis over a year-fixed effects analysis because of the small sample size in the global

production strategy (i.e., Quadrant 2). The year-demeaned data analysis is the same method with a least square dummy

variable approach in econometrics (Greene, 2004). Previous research uses the year-fixed effects model to control a timeseries aspect of multinomial logit model in a panel data model (e.g., Fischer & Sousa-Poza, 2009; Thursby et al., 2009). In

addition, the cross-sectional differences, in Table 3, are controlled by industry-fixed effects. The results from the yeardemeaned data are shown in Appendix B and are consistent with those found in Table 3.

Third, our sample is drawn from a set of European firms likely to share similar and stable CSAs. These CSAs are repeated

for the firms sharing the same nationality in the analysis. Therefore, potential statistical inferences exist within the

clustering of similar observations by country even though we use the CSAs as the control variables. We control for the

potential inferences by adding the country-fixed effects and dropping the CSA variables. Appendix C shows the results from

the country-fixed effects model. These results are fully consistent with those shown in Table 3. We are confident that our

findings are statistically sound and robust.

5. Discussion and conclusions

We build upon recent empirical research on the sales and assets of the world’s largest firms which demonstrate strong

intra-regional activity. For the first time, we examine the nature and extent of economic integration across 1100 firm-year

observations from Europe’s largest firms. We distinguish between strategies which determine intra-regional integration

(which accounts for 60% of the firms) and three types of global strategy. These are: global production (5% of all firms); global

sales (12% of all firms); and pure global integration (23% of all firms). We then apply a multinomial logit regression analysis

to demonstrate that the key determinant of a global production strategy is an FSA in R&D; in contrast the key determinants of

a global sales strategy and/or a pure global integration strategy are FSAs in firm size and managerial capability. This finding

implies that empirical work on the nature of integration strategy needs to reflect the decomposition between the regional

and global activities of MNEs.

Author's personal copy

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

503

5.1. Discussion

This study offers two insights into the international strategy literature. First, given economic integration and

liberalization, we examine the international and regional activities of MNEs to answer whether the upstream or downstream

activities of MNEs are global or regional. This contribution is directly related to the structure of the MNE. Second, we explore

which FSAs and CSAs induce the observed global (or regional) integration of the upstream and downstream activities of

MNEs. We find that different FSAs and CSAs determine global integration and regional integration of MNEs.

The results in this study present a number of implications both for the existing theory of the MNE and for practitioners.

While a simple global strategy has been popular in international business as well as in the mass media, we find that only a

few MNEs can integrate their upstream and downstream activities globally. In understanding internationalization strategy,

our results suggest that economic integration has a strong influence on the geographic tendency of MNEs at firm-level. Here

we examine the international activities of MNEs (i.e., sales and assets) whereas much of the literature on this topic has only

investigated the effects of economic integration on FDI at industry- and country-levels (Ghemawat, 2007; Oxelheim &

Ghauri, 2004) and on international trade (Fratianni & Oh, 2009).

We provide comprehensive and robust evidence to interpret the geographic pattern of MNE expansion. While some MNEs

target foreign regions to increase their sales and improve their production, most of their activities are bounded within their

home region markets. Thus, the conventional categorization used for domestic strategy and global (or international) strategy

(Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989; Kobrin, 1991) should be revisited. Regional economic integration and firm capabilities enable

firms to overcome foreignness within the home region. Johanson and Vahlne (2009) discuss such foreignness and call it the

liability of outsidership by using a concept of business network.

Regional integration strategy can be interpreted as a learning process for large MNEs (Rugman & Oh, 2010) in the same

way that domestic learning is an antecedent of internationalization for start-up firms (Sapienza, De Clercq, & Sandberg,

2005). Managerial capability and firm size are important FSAs of MNEs using global integration strategy. It appears that

MNEs develop their managerial capability (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989; Kogut, 1985; Porter, 1986) by managing their

subsidiaries in home region markets and increase their economies of scale (Levitt, 1983) by integrating their activities within

home region markets. Although the learning process may eventually lead MNEs to expand globally, the data show that the

process is very slow.

5.2. Limitation and future research

Although this study links regional economic integration and strategic management, we need to note some limitations.

First, we could not estimate the regional characteristics that lead to or deter global and regional strategies because we only

focus on a sample of European firms, which share the same regional characteristics. Therefore, the first extension of this

study should be to test all of the firm, country and region factors that determine global and regional strategies with a multiregion sample. Qian, Khoury, Peng, and Qian (2010) provide some groundwork on regional factors and find that regional GDP

growth, regional export growth and regional private consumption increase firm performance, while the regional inflation

rate reduces firm performance. In addition, longer longitudinal data would be beneficial because the country and region

factors do not likely vary much over time.

Second, our sample consists of large firms, which likely have experience, at least in their home region countries. However,

for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), regional integration is still a difficult decision as these enterprises will

likely face high barriers to integration. While most literature on this topic has focused on firm factors, it is still unclear as to

whether these SMEs are ‘born global’ or ‘gradual global’ (Hashai & Almor, 2004; Madsen & Servais, 1997). Recent evidence

shows that SMEs are ‘born regional’ rather than ‘born global’ (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009; Lopez et al., 2009). Examining

country and region factors will help us to better understand the internationalization process of SMEs.

Third, in this study, we focus on the firm-level drivers that determine regional and global integration. We find that each of

the four types of international strategy requires different FSAs (or resources). Indeed, developing several FSAs does not

guarantee global competitiveness. Some micro- and macro-level drivers may also determine the type of integration strategy

and, in fact, the international competitiveness of the firm. For example business–business relationships affect international

competences (Wu, Sinkovics, Cavusgil, & Roath, 2007) and determine the type of international expansion strategy used by

the firm. In addition to the country-level drivers that we use as the control variables in this study, other drivers, such as geopolitical factors, institutional factors, cultural factors, banking systems and the level of domestic competition, are likely to

influence a firm’s global and international orientation (Fan & Phan, 2007; Ragozzino, 2009). These topics are worthy of

further research, and we hope that this study has made a contribution to the understanding about global and regional

strategies.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge helpful comments from the editor, Pervez Ghauri, and two anonymous reviewers. Financial

support to the first author for this project was partially provided by a Standard Research Grant of the Social Science and

Humanities Research Council of Canada (File #: 410-2010-1589).

Author's personal copy

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

504

Appendix A. Robustness Check 1: Change categorization of four international strategies

70% threshold of intra-regional sales and assets is used for categorizing firms.

Base model is Quadrant 1 (Regional integration).

Firm characteristics

Firm size (lagged)

Managerial capability (lagged)

R&D capability (lagged)

Marketing capability (lagged)

Financial capability (lagged)

Growth orientation (lagged)

Home country characteristics

Domestic market size

Unemployment rate

Literacy

Infrastructure quality

Successful prediction rate

Number of observations

2 log likelihood

Pseudo-R Squared

Akaike Information Criterion

(1)

Quadrant 2

Global production

(2)

Quadrant 3

Global sales

(3)

Quadrant 4

Global integration

0.4101

(0.4225)

3.7564y

(2.3265)

27.8375*

(15.8752)

0.4850

(0.8344)

0.1276

(0.1195)

0.0003

(0.5125)

0.7663***

(0.2286)

5.3836***

(1.6892)

3.9351

(6.2512)

0.5297

(0.8261)

0.0204y

(0.0146)

0.1141

(0.2785)

0.8481***

(0.1675)

2.5793**

(1.0106)

4.8691

(4.2731)

0.9537**

(0.4746)

0.0013

(0.0066)

0.3873

(0.3087)

0.0935

(0.4702)

0.0686

(0.1335)

0.8575**

(0.4331)

0.0442**

(0.0184)

0.4199y

(0.2763)

0.3961***

(0.1282)

1.3080***

(0.4038)

0.0269**

(0.0109)

0.2939y

(0.1838)

0.5604***

(0.0769)

0.0599

(0.2381)

0.0117y

(0.0075)

73%

599

825.51

0.373

951.51

Note: * if p < 0.10, ** if p < 0.05; *** if p < 0.01. Two-tailed test. y if p < 0.10 at one-tailed test. Heteroskedasticity robust standard are in parentheses.

Industry-fixed effects and constant were estimated but not reported here.

Appendix B. Robustness Check 2: A year averaged cross-section regression

Use year-demeaned variables.

60% threshold of intra-regional sales and assets is used for categorizing firms.

Base model is Quadrant 1 (Regional integration).

Firm characteristics

Firm size (lagged)

Managerial capability (lagged)

R&D capability (lagged)

Marketing capability (lagged)

Financial capability (lagged)

Growth orientation (lagged)

Home country characteristics

Domestic market size

Unemployment rate

Literacy

(1)

Quadrant 2

Global production

(2)

Quadrant 3

Global sales

(3)

Quadrant 4

Global integration

0.7109y

(0.5294)

6.6055***

(2.3038)

72.3652**

(30.5499)

1.4515

(1.2304)

0.1369

(0.1682)

1.6142

(1.8390)

0.6774***

(0.2559)

8.4180***

(1.8371)

3.9051

(6.1611)

0.8817

(0.6831)

0.0208y

(0.0140)

0.7676**

(0.3532)

0.6928***

(0.1787)

3.7903***

(1.3123)

3.3079

(5.5613)

1.5309***

(0.5526)

0.0012

(0.0054)

0.2885

(0.3503)

0.8779*

(0.4661)

0.3142**

(0.1517)

1.5566***

(0.5657)

0.1707

(0.2717)

0.9763***

(0.1569)

1.9714***

(0.4714)

0.6642***

(0.2242)

0.8592***

(0.1127)

0.2275

(0.2334)

Author's personal copy

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

505

Appendix B (Continued )

Infrastructure quality

Successful prediction rate

Number of observations

2 log likelihood

Pseudo-R Squared

Akaike Information Criterion

(1)

Quadrant 2

Global production

(2)

Quadrant 3

Global sales

(3)

Quadrant 4

Global integration

0.0562*

(0.0308)

0.0496***

(0.0190)

0.0238*

(0.0122)

76%

599

721.98

0.447

951.51

Note: * if p < 0.10, ** if p < 0.05; *** if p < 0.01. Two-tailed test. y if p < 0.10 at one-tailed test. Heteroskedasticity robust standard are in parentheses.

Industry-fixed effects and constant were estimated but not reported here.

Appendix C. Robustness Check 3: Control country-fixed effects

Control country-fixed effects and drop country-level variables.

60% threshold of intra-regional sales and assets is used for categorizing firms.

Base model is Quadrant 1 (Regional integration).

Firm characteristics

Firm size (lagged)

Managerial capability (lagged)

R&D capability (lagged)

Marketing capability (lagged)

Financial capability (lagged)

Growth orientation (lagged)

Successful prediction rate

Number of observations

2 log likelihood

Pseudo-R Squared

Akaike Information Criterion

(1)

Quadrant 2

Global production

(2)

Quadrant 3

Global sales

(3)

Quadrant 4

Global integration

0.4339

(0.4196)

2.8528y

(2.2146)

73.4796***

(27.4452)

0.6886y

(0.4642)

0.1506y

(0.1008)

1.2997

(2.3809)

0.6371***

(0.1495)

6.2483***

(2.0485)

12.7249

(14.5304)

1.4115*

(0.7047)

0.0579***

(0.0079)

2.2636***

(0.6008)

0.4924***

(0.1187)

3.4928*

(1.8476)

4.4861

(10.8747)

1.9107***

(0.3050)

0.0034

(0.0079)

1.2563***

(0.4444)

81%

599

585.39

0.551

604.39

Note: * if p < 0.10, ** if p < 0.05; *** if p < 0.01. Two-tailed test. y if p < 0.10 at one-tailed test. Heteroskedasticity robust standard are in parentheses.

Industry-fixed effects, country-fixed effects, and constant were estimated but not reported here.

References

Agarwal, S., & Ramaswami, S. N. (1992). Choice of foreign market entry mode: Impact of ownership, location and internationalization factor. Journal of

International Business Studies, 23(1), 1–27.

Anand, J., & Delios, A. (1997). Location specificity and the transferability of downstream assets to foreign subsidiaries. Journal of International Business Studies,

28(3), 579–603.

Autio, E., Sapienza, H. T., & Almeida, J. G. (2000). Effects of age at entry, knowledge intensity, and imitability on international growth. Academy of Management

Journal, 43(5), 909–924.

Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1989). Managing across borders: The transnational solution. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1991). Global strategic management: Impact on the new frontier of strategy research. Strategic Management Journal, 12, 5–16.

Brenton, P., Di Mauro, F., & Lücke, M. (1999). Economic integration and FDI: An empirical analysis of foreign direct investment in the EU and in Central and Eastern

Europe. Empirica, 26, 95–121.

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. C. (1976). The future of the multinational enterprise. London: Macmillan.

Buckley, P. J., & Ghauri, P. N. (2004). Globalization, economic geography, and the strategy of MNEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2), 81–98.

Canning, D. (1998). A database of world stocks of infrastructure, 1950–1995. The World Bank Economic Review, 12(3), 529–547.

Caves, R. (1971). International corporations: The industrial economics of foreign investment. Economica, 38, 1–27.

Cavusgil, S. T. (1984). Differences among exporting firms based on their degree of internationalization. Journal of Business Research, 12, 195–208.

Cavusgil, S. T., & Zou, S. (1994). Marketing strategy-performance relationship: An investigation of the empirical link in export market venture. Journal of Marketing,

58(1), 1–21.

Chang, S. J. (1995). International expansion strategy of Japanese firms: Capability building through sequential entry. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 383–

407.

Chen, H., & Hu, M. Y. (2002). An analysis of determinants of entry mode and its impact on performance. International Business Review, 11(2), 193–210.

Collinson, S., & Rugman, A. M. (2008). The regional nature of Japanese multinational business. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(2), 215–230.

Author's personal copy

506

C.H. Oh, A.M. Rugman / International Business Review 21 (2012) 493–507

Contractor, F. J. (2007). The evolutionary or multi-stage theory of internationalization and its relationship to the regionalization of firms. In A. M. Rugman (Ed.),

Regional aspects of multinationality and performance (pp. 11–29). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Davidson, W. H., & McFetridge, D. G. (1985). Key characteristics in the choice of international technology transfer mode. Journal of International Business Studies,

16(2), 5–21.

Doz, Y., & Prahalad, C. K. (1988). Quality of management: An emerging source of global competitive advantage? In N. Hood & J. Vahlne (Eds.), Strategies in global

competition (pp. 345–369). London: Croom Helm.

Doz, Y., Santos, J., & Williamson, P. (2002). From global to metanational: How companies win in the knowledge economy. Boston: Harvard University Press.

Ethier, W. (2001). Regional regionalism. In S. Lahiri (Ed.), Regionalism and globalization: Theory and practice (pp. 3–15). New York: Routledge.

Fan, T., & Phan, P. (2007). International new ventures: Revisiting the influence behind the ‘Born-Global’ firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(7),

1113–1131.

Fischer, J. A. V., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2009). Does job satisfaction improve the health of workers? New evidence using panel data and objective measures of health.

Health Economics, 18, 71–89.

Fratianni, M., & Oh, C. H. (2009). Expanding RTA, trade flows, and the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(7), 1206–1227.

Ghemawat, P. (2001). Distance still matters: The hard reality of global expansion. Harvard Business Review, 79(8), 137–147.

Ghemawat, P. (2007). Redefining global strategy. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Giroud, A., & Mirza, H. (2006). Factors determining supply linkages between transnational corporations and local suppliers in ASEAN. Transnational Corporations,

15(3), 1–34.

Greene, W. H. (2004). Econometric analysis (5th edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Grosse, R. (1992). Competitive advantages and multinational enterprises in Latin America. Journal of Business Research, 25, 27–42.

Grosse, R. (2005). Are the largest financial institutions really global? Management International Review, 45(S1), 129–144.

Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1985). Do you really have a global strategy? Harvard Business Review, 63(4), 139–148.

Hashai, N., & Almor, T. (2004). Gradually internationalizing born global firms: An oxymoron? International Business Review, 13(4), 465–483.

Hejazi, W. (2009). Does China receive more regional FDI than gravity would suggest? European Management Journal, 27(5), 327–335.

Hennart, J.-F. (1982). The theory of the multinational enterprise. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hennart, J.-F. (2007). The theoretical rationale for a multinationality-performance relationship. Management International Review, 47(3), 423–452.

Hensher, D. A., Rose, J. M., & Greene, W. H. (2005). Applied choice analysis: A primer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hollenstein, H. (2005). Determinants of international activities: Are SMEs different? Small Business Economics, 24(5), 431–450.

Hout, T., Porter, M. E., & Rudden, E. (1982). How global companies win out. Harvard Business Review, 60(September–October), 98–108.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (2009). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of

International Business Studies, 40, 1411–1431.

Kim, W. S., & Lyn, E. O. (1990). FDI theories and the performance of foreign multinationals operating in the U.S.. Journal of International Business Studies, 21(1), 41–

54.

Kobrin, S. J. (1991). An empirical analysis of the determinants of global integration. Strategic Management Journal, 12, 17–31.

Kogut, B. (1985). Designing global strategies: Comparative and competitive value added chains. Sloan Management Review, 26(4), 27–38.

Kogut, B., & Singh, H. (1988). The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(3), 411–432.

Lasserre, P. (1996). Regional headquarters: The spearhead for Asia Pacific markets. Long Range Planning, 29(1), 30–37.

Levitt, T. (1983). The globalization of markets. Harvard Business Review, 61(3), 92–102.

Lopez, L. E., Kundu, S. K., & Ciravegna, L. (2009). Born global or born regional? Evidence from an exploratory study in the Costa Rican software industry. Journal of

International Business Studies, 40(7), 1228–1238.

Madsen, T. K., & Servais, P. (1997). The internationalization of born globals: An evolutionary process? International Business Review, 6(6), 561–583.

Morrison, A. J., Ricks, D. A., & Roth, K. (1992). Globalization versus regionalization: Which way for the multinational? In F. R. Root & K. Visudtibhan (Eds.),

International strategic management, challenges and opportunities (pp. 87–99). Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis.

Myers, S., & Majluf, N. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial

Economics, 13, 187–221.

Oh, C. H., & Oetzel, J. (2011). Multinationals’ response to major disasters: How does subsidiary investment vary based on the type of risk and the quality of country

governance? Strategic Management Journal, 32(6), 658–681.

Ohmae, K. (1985). Triad power: The coming shape of global competition. New York: Free Press.

Osegowitsch, T., & Sammartino, A. (2008). Reassessing (home-) regionalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 39, 184–196.

Oxelheim, L., & Ghauri, P. (2004). European Union and the race for foreign direct investment in Europe. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Porter, M. E. (1986). Changing patterns of international competition. California Management Review, 28(9), 9–40.

Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. New York: Free Press.

Qian, G., Khoury, T. A., Peng, M. W., & Qian, Z. (2010). The performance implications of intra- and inter-regional geographic diversification. Strategic Management

Journal, 31(9), 1018–1030.

Ragozzino, R. (2009). The effect of geographic distance on the foreign acquisition activity of U.S. firms. Management International Review, 49(4), 509–535.

Roth, K., & Morrison, A. J. (1992). Global strategy: Characteristics of global subsidiary mandates. Journal of International Business Studies, 23(1), 715–735.

Rugman, A. M. (1981). Inside the multinationals: The economics of internal markets. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rugman, A. M. (2005). The regional multinationals: MNEs and global strategic management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rugman, A. M., & D’Cruz, J. R. (1993). The double diamond model of international competitiveness: Canada’s experience. Management International Review, 33(2),

17–39.

Rugman, A. M., & Oh, C. H. (2007). Multinationality and regional performance, 2001–2005. In A. M. Rugman (Ed.), Regional aspects of multinationality and

performance (pp. 31–41). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Rugman, A. M., & Oh, C. H. (2010). Does the regional nature of multinationals affect the multinationality and performance relationship? International Business

Review, 19(5), 479–488.