Break Bulk Shipping Study

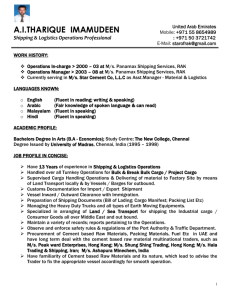

advertisement