Infrared Spectra and Characteristic Frequencies of Inorganic Ions

advertisement

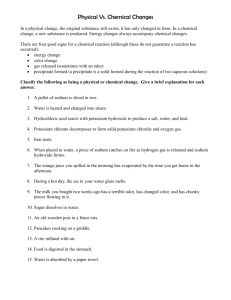

Infrared Spectra and Characteristic Frequencies of Inorganic Ions Their Use in Qualitative Analysis FOIL A. MILLER AND CHARLES H. WILKINS Department of Research in Chemical Physics, Mellon Institute, Pittsburgh 13, Pa. Polyatomic ions exhibit characteristic infrared spectra. Although such spectra are potentially useful, there is very little reference to them in the recent literature. In particular, the literature contains no extensive collection of infrared spectra of pure inorganic salts obtained with a modern spectrometer. In order to investigate the possible utility of such data, the infrared spectra of 159 pure inorganic compounds (principally salts of polyatomic ions) have been obtained and are presented here in both graphical and tabular form. A table of characteristic frequencies for 33 polyatomic ions is given. These characteristic frequencies are shown to be useful in the qualitative analysis of inorganic unknowns. Still more fruitful is a combination of emission analysis, infrared examination, and x-ray diffraction, in that order. Several actual examples are given. It is evident that a number of problems involving inorganic salts containing polyatomic ions will benefit by infrared study. The chief limitation at present is the practical necessity of working with powders, which makes it difficult to put the spectra on a quantitative basis. A LTHOUGH there has been a vast amount of work on the Raman spectra of inorganic salts ( 2 , 4 ) , the study of them in the infrared has been relatively neglected. Schaefer and Matossi (10) have reviewed work done up to 1930, most of which deals with reflection spectra. The most extensive surveys of infrared absorption spectra have been made by Lecomte and his coiTorkers (6, 7 ) , but unfortunately many of their data are somewhat out of date and are not always presented in the most useful form. References to studies on a few ions are given in the books by Wu (12) and by Herzberg ( 3 ) . There has recently been renewed interest in the detailed study of the infrared spectra of selected salts, as exemplified by the papers of Halford ( 8 ) , Hornig ( I I ) , and their coworkers. The well known Colthup chart ( 1 ) contains characteristic frequencies for nitrate, sulfate, carbonate, phosphate, and ammonium ions. An excellent recent paper by Hunt, Kisherd, and Bonham ( 5 ) contains the spectra of 64 naturally occurring minerals and related inorganic compounds. Aside from sixteen spectra in this latter paper, there is in the literature no compilation of infrared spectra of inorganic salts obtained with a modern spectrometer. I t therefore seemed worth while to make a fairly extensive survey to seek answers to the following questions: Is it generally possible to obtain good spectra? Do the ions possess frequencies which are sufficiently characteristic to be useful for analytical purposes? What is the effect on the vibrational frequencies of varying the positive ion? Is infrared spectroscopy useful in the analysis of salts? This paper presents the spectra from 2 to 16 microns of 159 pure inorganic compounds, most of which are salts containing polyatomic ions. A chart of characteristic frequencies for 33 such ions is given. The use of these data for the qualitative analysis of inorganic mixtures is demonstrated. Finally, a number of interesting or puzzling features of the spectra are described. A brief classification of the various types of vibrations in crystals may be appropriate. Ionic solids are considered fiist. In a crystal composed solely of monatomic ions, such as sodium chloride, potassium bromide, and calcium fluoride, the only vibrations are “lattice” vibrations, in which the individual ions undergo translatory oscillations. The resulting spectral bands are broad and are responsible for the long wave-length cutoff in transmission. I n a crystal containing polyatomic ions, such as calcium carbonate or ammonium chloride, the lattice vibrations also include rotatory oscillations. Of greater interest in this case, however, is the existence of “internal” vibrations. These are essentially the distortions of molecules whose centers of mass and principal axes of rotation are a t rest. The internal vibrations are characteristic of each particular kind of ion. I n molecular solids, such as benzene, phosphorus, and ice, the units are uncharged molecules held in the lattice by weak forces of the van der Waals type, andoften also by hydrogen bonds. The same classification into internal and lattice modes can be made. A few examples of such solids are represented in this paper (boric acid, and possibly the oxides of arsenic and antimony). Finally there are the covalent solids, such as diamond and quartz, in which the entire lattice is held together by covalent bonds. Here the distinction between lattice and internal vibrations disappears. One might a t first expect an ill-defined and featureless spectrum, but such is not the case. Actually there are bands that are very Characteristic. The situation is in some ways analogous to that in a polymer, which in spite of its size and complexity possesses a remarkably discrete spectrum. Silica gel is the only representative of this type included here. EXPERIMENTAL Origin and Preparation of Samples. Practically all the samples were commercial products of C.P. or analytical reagent grade. The samples were gound to a fine powder to minimize the scattering of light, and were examined as Sujol mulls. When there were spectral features that were obscured by the Sujol bands, the samples were either run as a dry powder or mulled in fluorolube (a mixture of completely fluorinated hydrocarbons. Fluorolube is a product of the Hooker Electrochemical Co., perfluoro lube oil of E. I. du Pont de Semours & Co.). Some compounds, such as ferric nitrate nonahydrate (No. 49) and calcium permanganate tetrahydrate ( S o . l50),seemed to mull up in their own water of hydration. When the fine powder x a s rubbed between salt plates, it acquired the appearance and feel of a typical mull, but no appreciable fogging of the salt plates resulted. For other compounds, such as potassium carbonate, breathing on the sample achieved the same result. This is not recommended, however, for it varies the water content unnecessarily, and with potassium carbonate some of the bands are shifted. Although these techniques are satisfactory for qualitative examination, it may be of interest t o list some other methods which have been mentioned in the literature for handling inorganic solids. Lecomte, who introduced most of them, has pointed out that a finely ground dry powder scatters very little radiation of wave length greater than 6 microns and consequently it may be used directly in that region (6, 7 ) . He also suggests coating 1253 ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1254 Table I. Index to Infrared Curves and Tables of Data Formula Boron hletaborate No. 1 2 3 Tetraborate Type Sulfur (Contd.) Sulfate Formula No. 4 5 6 Perborate 7 Misc. 8 9 Carbon Carbonate PbCOa SHiHCOa NaHCOa KHCOa 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Cyanide NaCN KCY 21 22 Cyanate KOCX AgOCN 23 24 Thiocyanate NHISCN NaSCN KSCN Ba(SCN)z. 2Hz0 Hg(SCS)z Pb(SCN)z L1&03 NazCOz KzCOa 3hfgCOs hlg(OH)n.3HzO CaCOa BaCOa coco3 Bicarbonate Silicon Metasilicate Silicofluoride Silica gel Sitrogen Nitrite 31 32 NazSiFs SiOr , XHZO 33 34 Nah-02 KNO? AgNOz Ba(SOz!z Hz0 36 36 37 38 Nitrate Subnitrate 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 BiOSOz.Hz0 Phosphorus Phosphate, tribasic Phosphate, dibasic Thiosulfate Metabisulfite 60 61 62 63 64 65 Selenium Selenite 104 105 106 NazSeOa CuSeOa, 2H20 107 108 Selenate (NHhSeOi NazSeOi. lOHzO KzSeOh CuSeOl. 5HzO 109 110 111 112 Chlorate NaC108 KClOa Ba(Cl0s)z.Hz0 113 114 115 Perchlorate NHiClOi SaClOa, H20 KClOa Mg(CIO*)z 116 117 118 119 NaBrOa KBr03 AgBrOa 120 121 122 Bromine Bromate Iodine Iodate Periodate 123 124 125 KIOi Vanadium Metavanadate Chromium Chromate Dichromate Molybdenum Molybdate Heptamolybdate Tungsten Tungstate Manganese Permanganate 66 67 68 103 Persulfate 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 67 58 59 (NHdzHPOi hazHPOi.12HzO KiHPOi MgHPOi. 3Hz0 CaHPOa. 2H20 BaHPOi Bisulfate Complex ions Ferrocyanide 126 127 128 (NHl)zCrOa NazCrOi KzCrOa MgCrO4.7HzO BaCrOb ZnCrOa, 7HzO PbCrOa Alr(CrOd8 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 (NH4)zCrzOi NazCrtO~.2H20 KzCrrOr CaCrzOl.3HzO CuCrzOr ,2Hz0 137 138 139 140 141 NazMoOi, 2HzO Kd~foOi.5HnO 142 143 (~Hdahfo7O24.4HzO 144 NanWOi.2HzO KzWOI CaWOi 145 146 147 NaMn04.3HzO KMnOi Ca(MnOi)*.lHzO Ba(Mn0h 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 71 Ferricyanide NarFe(CN)a. 10HzO KdFe(CN)o.3Hn0 c a ~ F e ( C N ) a12Hz0 . KaFe(CN)s Orthoarsenate, tribasic Orthoarsenate, dibasic Car(.4sOi)z NazHAsO4.7HzO PbnHAsOi 72 73 74 Cobaltinitrite NasCo(N0r)o 156 Hexanitratocerate (NHdzCe(N0ah 157 Orthoarsenate, monobasic KHz.4~04 75 Oxide AszO: 76 NHhCl BaCln. 2Hz0 158 159 Nujol, fluorolube 160 SbzOa Sbzos 77 78 (NHI)ZSOSHzO NazSOa KzSOa 2Hz0 CaSOa 2Hz0 BaSOa ZnSOs 2H20 79 80 81 82 83 84 69 70 Antimony Oxide Sulfur Sulfite Chlorine Chloride Mulling agents V O L U M E 24, NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 Table 11. v w = very weak w = weak C m . - 1 Microns I 1. Sodium metaborate NaBOz 862 11 60 w 925 10 80 vs, b 8 50 ni 1175 1310 7 64 rs 1655 6 05 m 3470 2 85 YS, vb 2. M a nesium metaborate M%Bo~)~.~H~o 808 838 892 952 1005 1085 1130 1220 1370 1420 1640 3360 3500 12.4 11.95 11.2 10.5 9.95 9.2 8.8 8.2 7 3 7 05 6 1 2 98 2 86 3. 960 1340 1380 3280 4. ~~ 5. w s s w s s Lead metaborate Pb(B0z)n. HzO 1 0 . 3 s, vb 7.45 m 7.2 Nujol? 3.05 m Sodium perborate NaBOs.4HzO vw 13 0 w 12 0 11 75 w vw 11 4 TS 10 7 9 8 8 9 3 m 8 5 s 8 05 s 6 05 w vs 3 0 Boric acid &BO3 12.4 m vw 11 3 8.37 s,sp 6.9 vs 3.15 s 8. 807 885 1195 1450 3270 s Manganese tetraborate MnBiOi.8HzO 10.1 9 . 4 1 s , vb 8.7 7.3 s 6.9 m 6.1 w 2.95 8 7. 770 833 852 877 934 1020 1075 1175 1240 1655 3330 m Potassium tetraborate K2BiOi. 5Hn0 14.2 vw 12.8 vw 12.0 s 10.9 s 10.0 s 9.45 vw 9.2 s 8.85 v w 8.65 w 8.05 m 7 . 6 2 sh 7.45 s 6.95 s 6.05 w 4 03 vw 3.03 s 2.95 s 2.81 s 705 782 833 918 1000 1060 1085 1130 1155 1240 1315 1340 1440 1655 2480 3330 3390 3560 990 1065 1150 1370 1450 1640 3390 w s Sodium tetraborate NazBiOi. lOHzO 14.05 w 12.9 w 12.1 s 10.6 s 10.0 s w 9.3 8.85 m 7.95 m 7.85 m 7.35 vs 7.05 vs 6.85 Nujol? 6.05 m 3.0 vs 712 775 828 843 . 1000 1075 1130 1260 1275 1360 1420 1460 1650 3330 6. s m vw 1255 Positions and Intensities of Infrared Absorption Bands s = strong m = medium verystrong s h = shoulder b = broad = KBr region (15-25~) eyamined vs = * Microns I 9. Boron nitride BN 810 12.35 w 1390 7.2 s Cm. -1 Lithium carbonate LipCOp 1 1 . 5 8 in 6.92 s 6.7 s 10. 864 1445 1490 11. 700 705 855 878 1440 1755 2500 2620 -3000 Sodium carbonate NapCOa 14.3 in 14.2 m 11.7 v w 11.4 s 6 . 9 5 vs 5.7 m, sp 4.0 m 3 . 8 2 vw 3.3 m, vb - 12. Potassium carbonate KzCOa 865 11.55 m 1 1 . 1 vw 900 6.9 vs 1450 -3220 3.1 m, vb - 13. M a nesium carbonate basic 3 M g e O ~Mg(OH)n.3H;O . 1 2 . 5 vw 800 11.7 vw 855 vw 885 11.3 7 . 0 vs 1430 vs 1490 6.7 2.9 111, vb 3450 14. Calcium carbonate CaCOa 14.0 w 11.4 s , s p 7 . 0 vs 5.6 vw 3.95 vw 715 877 1430 1785 2530 15. Barium carbonate BaCOa 697 1 4 . 3 5 vi 858 11.65 s , s p 6 . 9 5 vs 1440 16. 747 865 1450 -3330 Cobaltous carbonate COCOS 1 3 . 4 vw 11.55 m 6.9 vs 3 . 0 w , vb 17. 685 840 1410 18. 703 832 993 1030 1045 1325 1400 1620 1655 1890 2550 3060 3160 19. 662 698 838 1000 1035 1050 1295 1410 1460 1630 1660 1900 2040 2320 2500 2940 Lead carbonate PbCOa 14.6 w 1 1 . 9 vw 7.1 YS Ammonium bicarbonate NHiHCOi 14.25 12.02 10.08 9.7 9.58 7.55 7.15 6.17 6.05 5.3 3.92 3.27 3.17 s s, sp s w, SP w , SP vs, b vs, s p s s w m VS,SP 20. 705 833 990 1010 1370 1410 1630 2380 2600 2950 E} 5.27 m 5 vw w (COZ?) s. b hficrons I Potassium bicarbonate KHCOa 14.2 s 12.0 s , s p 10.1 s 9.9 9 m, sh 7.3 vs 7.1 6 . 1 5 vs 4.2 w 3 . 8 5 s , vb 3.37 m s p = sharp 22. Potassium cyanide KCN (KHCOa, K ~ C O Simpurities) 1 2 . 0 m , imp. 833 882 11.35 vw, imp. 1440 6 . 9 5 s , imp. 1635 6.12 8 2070 4.83 s 23. Potassium cyanate KOCN (KHCOa impurity) 706 833 980 1010 1210 1310 1410 1640 2130 2630 1210 1310 1345 2170 3450 25. 1420 1650 2050 2860 3060 3149 26. 758 950 1620 2020 3330 27. 746 945 1630 2020 3400 28. 1630 2060 3500 29. 835 1105 1150 1370 1615 2090 3450 14.17 12.0 10.2 9.9 8 25 7.65 7.1 6.1 4.7 3.8 s. imp. s,rmp. m, !mp. m , imp. m , sp. n', s,p. v s , !mp. vs, imp. s , yb s , imp. 24. Silver cyanate AgOCN 8 . 2 5 vw 7.65 w 7 . 4 3 vw vs 4.6 2.9 vw Ammonium thiocyanate NHiSCN 7.05 s 6 05 m 4 88 s 3.5 m 3.27 s 3.18 s Sodium thiocyanate NaSCN w 13 2 vw, b 10 5 6 18 m 8 4 9 ni 3 0 Potassium thiocyanate KSCN 13.4 m 10.6 vw, vb 6.13 m s 4.9 2.95 m Barium thiocyanate Ba(SCN)z. 2HzO 6.15 m 4 . 8 5 vs, s p 2 . 8 5 vs Mercuric thiocyanate Hg(SCN)z 1 2 . 0 vw 9 . 0 5 vw vw 8.7 s 7.3 w 6.2 4.78 8 2.9 w 30. Lead thiocyanate Pb(SCN)E 2030 4.93 8. sp w 2080 4.8 imp. = impurity Cm. -1 Microns I 31. Sodium metasilicate NarSiOa. 5Hz0 715 14.0 s 775 12.9 s 832 12.03 s 980 10.2 YS 8.9 m 1125 8.58 m 1165 5.9 m 1695 2330 4.3 m 3280 3 . 0 5 vs, vb 32. 21. Sodium cyanide NaCN (NasCOa impurity) 11.55 m , imp. 865 1310 7 . 6 5 vw 1460 6 . 8 5 vs,imp. 6.1 m 1640 2080 4.8 s 4.5 w, vb 2220 3.0 m , vb 3330 vs, sp Sodium bicarbonate NaHCOs 1 5 . 1 5 w (COZ?) 14.35 R 11.95 10.0 9.65 9.55 7.73 7.1 6.85 4.9 4.3 4.0 3.4 Cm. -1 vb = verybroad Potassium metasilicate KtSiOa 13.0 vw 1 0 . 1 vs, vb 6.15 vw 3.0 m 770 990 1625 3330 33. Sodium silicofluoride Na2SiFa 13.73 v s m,sh 12.7 9.05 vw 728 790 1105 34. Silica gel SiOz. xHzO 12.5 10.55 9,l5 8.4 6.1 3.0 800 948 1090 1190 1640 3330 35. s,sh vw m Sodium nitrite NaNOz 831 1250 1335 12.03 8.0 7.5 36. w w vs m, s p vs m,sh Potassium nitrite KNOz 830 1235 1335 1380 2560 3450 12.05 s , s p 8.1 vs 7 . 5 m, sp 7.25 m 3.9 vw 2.9 vw 37. 833 848 1250 1380 Silver nitrite AgNOz 12.0 w 11.8 v w vs 8.0 7.25 vs 38. Barium nitrite Ba(N0n)z. H20 820 1235 1330 1640 3360 3510 12.2 8.1 7.53 6.1 2.98 2.85 39. m , SP ;:i5} 6.13 w 5.75 w w 3410 2.93 40. 836 1358 1790 2428 41. 824 1380 1767 42. 803 835 1348 m m m ,sp Ammonium nitrate NHiNOa 12.05 w 830 1340 1390 1630 1740 733 w vs Sodium nitrate* NaNOa 11.96 m , s p 7.36 vs 5.59 v w 4.12 vw Potassium nitrate KNOI 12.14 m, s p 7 . 2 5 vs 5 . 6 6 vw Silver nitrate AgNOa 13.64 vw 12.45 11.98 w vw 7.42 YB ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1256 Table 11. vw = very weak w = weak Cm. - 1 RZicrons I 43. Calcium nitrate Ca(N0a)z 820 12.20 w 9.58 vw 1044 s 1350 7 4 1430 7.0 s 6.1 m 1640 s 3450 2.9 44. 13.72 6 , SP 12.24 S , S P 7 . 4 0 vs 7.05 m,sp 5 64 w, SP 4.15 b UT, 46. Cupric nitrate Cu(N0a)z. 3Hz0 11.96 w 7.26 vs 6.30 6, SP 5 58 v w 4 . 1 1 vw 3 15 w 2.98 s, b 47. 807 836 1372 1640 3230 3410 726 807 836 1373 Lead nitrate Pb(N0a)z 13.77 u' 12.39 v w 11.96 w, sp 7.28 w 835 1361 1613 1785 2440 3230 49. Ferric nitrate Fe(NOa)a,9HzO 11.98 w 7 . 3 6 vs 6.19 m 5.6 vw 4.1 vu. 3 . 1 s , vb 50. 816 1325 1380 1640 3390 * 1 55. Manganese phosphate, tribasic Mns(P0a)z. 7Hz0 935 10.7 vw, sh 980 10.2 w 1020 9.8 s 1040 9.6 ?sh 1070 9.35 s 1145 8.75 w 1250 8.00 w 1300 7.7 w 2470 4.05 vw 3170 3,l5'! 3330 3450 i:: I 56. Nickel(ous) phosphate, tribasic Nia(P0a)~. 7Hz0 735 13.6 w. vb 877 11.4 w Rh 943 io 6. w., .~. 100.5 9.95 s 1060 9 . 4 5 w, sh -1440 ?) 6 . 9 5 w (Sujol 1595 6.27 w -3030 3.3 s 3450 2.9 m,sp - 57. + Lead phosphate, tribasic Pbs(P0a)z 59. Chromic phosphate, tribasic CrPOa. H?O 1030 9.7 vs, vb 1625 6.15 w 3230 3 . 1 E, b 60. Ammonium phosphate, dibasic (NHa)zHPOc Potassium phosphate, tribasic KaPOi 10.0 vs, vh 1000 6 . 3 w , vb 1590 3180 3.15 vs, b 53. Magnesium phosphate, tribasic Mga(POajz.4HzO 768 13.05 w, b 887 1 1 . 3 vw, b 1% 1040 1135 1155 1230 1640 3260 3460 %E5] 8.83 8.65 8.13 6.1 3.07 2.9 ," m w,sh w m s m, s h vb = very broad sp = sharp m ::::} - 71. 64. Calcium phosphate, dibasic CaHPOa. 2H20 880 11.35, m 990 10.1 1050 9.5 1 s, r b 1125 8.9 J 1350 7.4 ? 1650 6.07 m -2270 4.4 m, vb -3000 3.3 m 3610 2.85 v w , sh 65. Sodium metaarsenite NaAsO, 14.36 vs, b 13.35 m 12.9 w,ah 12.0 s, sp 11.8 s , s p 7.06 v w 6.85 m, sp 2.90 w , b 697 748 775 833 848 1420 1460 3450 -- 72. Calcium orthoarsenate, tribasic Ca,(AsO4)2 Barium phosphate, dibasic BaHPOa 73. 2440 2700 66. 900 1080 1275 1420 1440 -1610 -2270 2900 3050 67. 4.1 3.7 w w Ammonium phosphate monobasic NHaHzPOa 11.1 w , vb 9.25 m, b 7.85 m 7.05 w, sh 6 . 9 5 rn 6.2 w, vb 4.4 w, vb 3 . 4 5 w, sh 3.28 m -- Sodium phosphate, monobasic NaH2POa. HzO 1640 2850 2820 Sodium orthoarsenate, dibasic NazHAsOa.7HzO 712 836 1175 1280 1640 2175 2380 -3130 - 74. Lead orthoarsenate, dibasic PbzHAsOc 743 13.45 m , b 800 12.5 vs 75. Potassium orthoarsenate, monobasic KHzAsOa 750 850 1020 1266 1585 -2275 -2740 -- 6.1 m , vb 4 . 2 5 s, b 3.55 s , b 803 840 1040 77. 61. Sodium phosphate, dibasic NanHPOa. 12HzO 11,55 9 865 1 0 . 4 5 w, sh 958 10.15 S 985 1070 9 . 3 5 17s 1125 8.9 u-,sh 1145 8 . 7 5 vw, sh 1185 8 45 w 126.5 7.9 W 1630 6.13 m -2220 4 . 5 w , vb 3280 3 . 0 5 vs, vb - 62. imp. = impurity Cm.-' hlirrons I 70. Calcium phosphate monobasic, Ca(H2POa)z. ~ 2 0 670 14.9 m, vh 855 w, r b 885 915 10 9 ' v w , sh 950 10 5 s. h 1085 9 2 s,b 1160 8 6 w 1235 8 1 s,b 1640 6.1 m 2320 4.3 m, vb -2980 3.35 s , v b 76. 51. 52. 35 Copper(icj phosphate, tribasic C~a(POa)2.3Hz0 645 15.5 m 855 11.7 m 925 10.8 s 960 10.4 s 1010 9.9 s 1070 9.35 s 1100 9.1 m , sh 8.75 m 1140 7.75 m 1290 3390 2.95 m 58. b = broad Cm. -1 Microns I 63. Magnesium phosphate, dibasic MgHP04.3H20 882 11.35 m 1020 9.8 s 1055 9.5 s 1160 8 6 8 N Bismuth subnitrate BiONOa. H20 12 27 vw 7.55 s 7.25 vs 6.1 vw 2.95 m, b Sodium phosphate, tribasic NaaPOa. 12H20 694 1 4 . 4 real? 1000 1 0 . 0 vs 6.9 vw 1450 6.03 m 1660 3200 3.13 vs, b ah = shoulder = I<Br region (15-25p) examined Microns I Calcium phosphate, tribasic Caa(P0a)z 10.4 v w 962 1030 9 . 7 ' YS, vb 1085 9.2 3230 3 . 1 m, b Cobaltous nitrate Co(NOa)2.6HzO 12 4 vw, r b 11 96 w, 6p 7 29 vs 6 1 m 3 1 m , sh 2.93 s 48. vs = very strong 54. Barium nitrate Ba(N0s)t 729 817 1352 1418 1774 2410 s = strong Cm. - 1 Strontium nitrate Sr(NOdz 45. 836 1378 1587 1790 2431 3170 3360 Positions and Intensities of Infrared Absorption Bands (Continued) m = medium Potassium phosphate, dibasic KzHPOc 837 11.95 s 934 10.7 s 990 1 0 . 1 vs, vb 1110 9.0 w,sh 1350 7.4 m, sp 1835 5.45 m 2380 4.2 m 2860 3.5 m 68. Potassium phosphate monobasic* KHzPOc 538 18 59 m 900 1 1 . 1 m, vb 1090 9.15 m , b 1300 7.7 m 1640 6 1 m, b 2320 4.3 m, b 1105 1410 3075 1 s. b m Arsenic trioxide AS?Oa 1 2 . 4 5 vs 11.9 w, sh 9 6 vw, b 78. Antimon pentoxide Sbr8r 685 1 4 . 6 v w , real? 740 13.5 s , v b 3225 3.1 w, b 69. iii: m, b m, b vw, b m, vb m ,vb m. vb Antimony trioxide Sb2Oa 14.5 w 1 8 . 5 vs 1 0 . 5 vw, b 690 740 950 79. Magnesium phosphate, monobasic Mg(H2POa)z 755 13.2 w. vb 943 10.6 1040 9.6 m,vb 1150 8.7 J 1235 8.1 w , sh 1640 6.1 m 13.3 11.75 9 8 7.9 6.3 4.4 3.85 Ammonium sulfite (NHa)zSOa. H20 9 . 0 5 vs, b 7 . 0 8 v s , sp 3.25 s 80. 960 1135 1215 Sodium sulfite Na2S03 10.4 rs,b 11.35 w 8 2 vw V O L U M E 24, NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1257 Table 11. Positions and Intensities of Infrared Absorption Bands (Continued) vw = very x e a k Cni.-' xv = weak I Nicrons 81. Potassium sulfite K?SOS.2H20 913 10.6 vs, vb 1100 9.1 vs, b 1175 8.5 s 6.07 v w 1645 5.3 vw. 1885 2.95 m 3390 82. Calcium sulfite CaSOs. 2HzO :$; i::: 653 15.3 1100 1210 1625 3400 } m = medium 86. Lithium sulfate* LizSOa. H z 0 15.77 m 634 815 12.25 v w , real? 1020 9.8 v w 1110 9.0 T S 1170 8.55 m, sh 1 1380 7.25 Nujol 1625 6.15 m , sp 2.88 m 3470 + 87. Sodium sulfate NazSOa 645 15 5 w 1110 9.0 vs 88. Potassium sulfate* KzSOa 1110 9 0 vs 667 1010 1130 1630 1670 2200 3410 90, 660 825 1025 1135 3225 Calcium sulfate CaSOa. 2Hz0 14.95 s 9.9 w, sh 8.85 6.13 5,95 4.55 2.93 vs, vb s. sp w m. b s, b Manganese sulfate MnSOd.2HpO 15.15 m 12.1 s 9.78 nr 8.8 3.1 vs, vb s, b 91. Ferrous sulfate* 611 990 1090 1150 1625 3330 FeSOh. 7Hz0 16.37 s , v b 10.1 vw 9.2 vs, vb 8.7 m,sh 6.15 m 3.0 s , b sh = shoulder 101. Microns - 93. 1080 1630 1650 3195 94. Zirconium sulfate* ZrSOa. 4Hz0 15 95 w 15.4 w 13.8 w 13 0 v w , sh 10 9 v n , sh 9 7 w, sp 9.25 vs, vb 6.12 m 6.05 m 3.13 s Chromium potassium sulfate Crz(SO4)d . KzSOa. 24Hz0 1090 9.2 vs 1660 6.05 w, b 2.97 m 3370 95. Ammonium bisulfate NHaHSOa 855 11.7 m. b 1035 9.65 m, b 1180 8.5 m, b 1410 7.1 vw 3180 3.15 m , Ammonium sulfate 85. (NHa)zSOa 15.5 w 645 9.05 vs. b 1105 1410 7.1 vs, sp 5 , 7 5 vw 1740 3.25\ 3032 3.161 s * s p 3165 89. very strong - b = broad = KBr region (15-25p) examined Cm. -1 627 650 720 770 920 1030 84. Zinc sulfite ZnSOs.2HzO 11.7 s , vb 10.57 w 9.8 s 9.1 m 8.6 m 6.13 m 3.15 2.951 * I m, b ~ sh , vw,vb 83. Barium sul5te BaSOa 638 15.7 m 917 10.9 vs. b 990 10.1 w 1070 9.35 m,vb 1200 8.35 m 1410 7.1 v w YS = 92. Copper sulfate cusoa 680 14.7 m 805 12.45 m 860 11.6 m 1020 9.8 w, sp 1090 9 . 2 vs, vb 1200 8.35 s 1600 6.25 w, sh -3300 3.15 s , b Cm. -1 9.1 8.3 vw 6.15 m,sp 2.94 s , s p 855 945 1020 1100 1160 1630 3170 3390 s = strong 96. Sodium bisulfate NaHSOh 655 215.3 ni 12.95 vw 773 - 665 1000 1115 1645 2250 3200 3360 3450 Magnesium thiosulfate MgSzOr .6Hz0 -1n.O s 10.0 s 8.95 vs 6.08 m 4 . 4 5 > v. vb 3.13 2.981 s 2.9 ) 102. Barium thiosulfate BaSzOs.U2O m s m vw m 820 848 877 1005 1065 1160 1280 1325 1640 2600 2900 Potassium bisulfate KHSOa 12.2 w , s h 11 8 s 11.4 s 9.95 5 9.37 S , SP 8.6 vs,b 7.78 s 7.55 w, s h 6.1 w m. vb 3.85 v w 3.45 s , v b 2:: j> 98. Ammonium thiosulfate (NHdzSzOa 953 10.5 s 1065 8.4 s 1390 t.18 s 1650 6.05 w 2960 3.4 s , vb 99. Sodium thiosulfate Na&03.5H20 677 14.8 s 757 13.2 v w , sh 1000 10.0 vs 1125 8.9 8.6 1165 1630 G,l5 w 1660 6.03 m ) '" 2080 3390 2.95 vs 100. Potassium thiosulfate KzSzOs. H20 658 15.2 676 14.8 10 03 s 995 1120 8 95 v s 1625 6 15 v w 3300 3 03 w Cm. -1 Potassium selenate KsSeOa 12.35 v w . s h 12.13 s , sp 11.67 11.42 11.15 9.22 9.0 8.75 7.28 5.73 4.18 89? Sodium metabisulfite* Na&Os 4.56 m 21.91 14..58 .: I2 a31 m 18.81 m 1.5. 171 660 fifi7 973 1,j.n / in.25 0.4.5 8..5 7.9 lofin 11x0 1265 112. vs v w , sh Potassium metabisulfite KZSZO5 RR2 1,5.l rn 475 1 0 . 2 5 cs iofin 4.ii 10x0 9 . 2 i ni 104. 1105 9 0.5 R. i 105. fi?7 702 865 lOR0 1085 -1190 1280 14211 3260 ni 7's 8.0 r w , ~ h Ammonium persulfate (NHi)zSzOq 15.7 vw 14.23 s 12.5- w 11 ..?.a 7-w - 4.45 4.23 8.4 7.8 7.0.5 s,sp 3.07 E m, s , 3p I060 9 1? 1270 7 88 1100 7 7 3300 3 02 w 107. 720 788 112.5 1450 3330 r Sodium selenite NazSeOa 18.7 vs 12.7 s 8.4 w , h 6.9 Nuiol ? 3.0 w, b + - 109. @ 860 1235 1420 1640 2320 -3140 Ammonium selenate (NH4)zSeOa 13.0 \ i:;i31 vs,vb 11.63,' 8.1 w 7.03 s 6.1 m 1.3 ni 3.18 v s - 938 962 1610 3S40 3570 116. vs 108. Copper selenite CuSe08.2Hz0 714 14.0 v s 768 17.0 m.sh 807 12.4 r w , s h 918 10.9 m 1570 6.35 m 1650 6.05 w 4.4 vw, v b 2270 -3120 3.2 1 3450 2.9 1 770 114. vs w, sp w,8p Copper selenate CuSeOa. 5Hz0 13.0 m, b 11.65 s 10.85 m 6.25 m , s p 3.1 \ 2.951 113. 935 965 990 vw vw Sodium chlorate NaClOa 10.7 s , s p 10.35: 10.1 ( vs Potassium chlorate KClOa 10.65 w 10.4 YS t:;:5] KzS201 14.1 770 858 922 1600 3220 3390 vw m vw 115. Barium chlorate Ba(ClOa)n.H z O SD w,sh v' 106. Potassium persulfate 710 1080 1110 1140 1375 1745 2390 vs 1's I Microns 875 857 103. imp. = impurity 110. Sodium selenate Na~Se04.10H~O 735 13.6 vw, sh 793 12.6 vs 838 11.95 vs 573 11.45 vs I105 9 05 m 1125 8.9 m, s p 8.6 w 1165 1240 8.07 m 1390 7.2 s 1640 6.1 m 2350 4.25 s 3220 3.1 m 3500 2.85 s , s p 810 824 793 97. sp = sharp 111. 117.5 1250 8.0 8.1 6.02 3.85 2.88 I Rlicrons - vb = very broad 1060 1136 1420 3330 vs. v b 6.2 m,s p 2.83 s , s p 2.80 s , s p Ammonium perchlorate NHaClOa 9.45 v s 8.8 s , s h 7.05 s 3.0 s, sp 117. Sodium perchlorate 1100 1630 2030 3570 NaCIOI. HzO 0.1 vs, b 6.14 s , s p 4.93 vw 2.80 s , sp 118. Potassium perchlorate KClOc w 637 15.7 940 10.65 v w 1075 93 s 1140 8 . 7 5 s . SI1 1990 5,02 cw 119. Magnesium perchlorate MgClOi 652 15.35 rn 10.58 w 943 10.4 w 962 9.45 vs 1060 8 . 85 \I 1130 6.13 s , sp 1625 4.8 P , vb 2100 2.83 s 3540 ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1258 Table 11. Positions and Intensities of Infrared Absorption Bands (ConcEuded) vw = very weak K = weak m = medium C m - 1 Microns I 120. Sodium bromate NaBrOz 807 1 2 . 4 vs 121. Potassium bromate KBrOa 12.65 vs 790 122. 765 797 1280 Silver bromate AgBrOs 13.08 s 12.55 vs 7 . 2 5 Nujol ? + 123. Sodium iodate NaIOs ;;; i;:?} vs 800 m 12.5 124. 738 755 800 Potassium iodate KIO? 13.55 vs 13.25 s 12.5 w 125. Calcium iodate Ca(I0s)z. 6HzO 13.35 m 748 13.15 m 760 775 12.9 s 817 12.25 8 827 1 2 . 1 vw, sh 838 11.93 v w , s h 1610 6.20 w , s p 3350 3450 i::8} 126. 848 Potassium periodate KIOa 1 1 . 8 vs 127. Ammonium metavanadate NHdVOa 690 14.5 s, vb 843 11.85 s 888 11.25 s 935 10.7 s 1415 7.08 s , sp 3200 3.12 8 , sp 128. 693 828 910 935 957 3450 129. 74 5 843 865 935 1410 1650 2860 2990 3120 130. 680 820 855 890 915 1665 2125 3170 131. 858 935 Sodium metavanadate NaVOa . 4 & 0 1 4 . 4 s, b 12.08 s 1 1 . 0 vw 10.7 10.45} 2.9 w, b Ammonium chromate (NHd)zCrO4 13.4 m 11.85 m, ah 11.55 vs, b 1 0 . 7 m. sh 7.1 8 6.05 m 3.5 m.sh 3.35 s 3.2 m,sh s = strong 1 10.90 6.0 4.7 3.15 * = very = KBr strong s h = shoulder b = broad region (15-25p) examined Cm.-1 Microns Z 132. M a nesium chromate MgErO4.7HzO 695 14.4 w, v b 765 1 3 . 1 w, b 855 11.7 m , s h 877 1 1 . 4 vs 1620 1650 ::I%} 2270 4.4 m, b 3260 3 . 0 7 vs, b 133. Barium chromate BaCrOa i i g ii:z5} vs b 930 3450 142. 1 135. Lead chromate PbCrO4 825 855 vw. vb 885 11.3 ::::1 vs.b Potassium chromate KzCrOh 11.65 w, sh 11.45 vs 10.7 s = very broad 820 855 900 1680 3280 143. Copper dichromate CuCrz01.2HzO 1 3 . 3 s , vb 10.65 s 6.15 m 2.9 s Sodium molybdate NazMoO,. 2 H ~ 0 12.2 vs 11.7 m 11.1 m , s p 5.95 w 3.05 s Potassium molybdate KzMoOa.5HzO 1 2 . 1 va 11.1 m 3.02 m 825 900 3310 144. Ammonium heptamolybdate (NHa)nMoiOzi.4HzO 663 1 5 . 1 vs 836 11.95 m 877 11.4 vs 913 10.95 w , s h 1420 7.05 s 1640 6.1 w 3080 3.25 s, b sp = sharp 136. 745 950 1010 1300 1625 3460 3520 Aluminum chromate Alr(CrO4)s 13.4 s , v b 10.5 s , b 9.9 s 7 . 7 vw 6.15 m ;:ii} 137. Ammonium dichromate (NH4zCrzOi 730 1 3 . 7 vs 877 11.4 m 900 11.1 m 925 10.8 s , s h 950 10.55 s 1410 7.1 s,sp 2850 3.5 m, sh 3060 3170 ::%} 145. 810 822 8.50 925 1670 3310 Sodium tungstate NazW04.2 H z 0 12.35 w , s h 12.15) 11,751 vss 10.8 w 6.0 w 3.02 s 146. Potassium tungstate KsWOc 750 13.3 vw 823 1 2 . 1 5 vs, b 925 10.8 w 1680 5.95 w 3170 3.15 m 3320 3.01 w,sh 147. 794 1640 3390 Calcium tungstate Caw04 1 2 . 6 vs, vh 6.1 w 2.95 m 152. Sodium ferroc anide NaaFe(CN)s. lOd0 1625 6.15 s , s p 2000 5.0 vs 2020 4.95 m, sh 153. 930 995 1630 1650 2015 3410 3510 Sodium dichromate NalCrzOr .2Hz0 13.55 vs 12.8 m 11.25 8. sp 11.0 m , s p 9 . 0 7 vs 7.2 Nujol 1 8 , SP 2.85 8 ;:A;} + 139. 568 760 795 885 905 920 940 1305 Potassium dichromate* KnCrzOi 17.61 w 13.15 vs 12.55 m 11.3 m, SP 11.05 m , s p 10.85 w , ~ h 10.65 vs, b 7 . 6 5 vw 148. Sodium permanganate NaMn04.3Hz0 840 1 1 . 9 vw, sh 896 11.15 vs 1625 6.15 s,sp w,b 3510 2.85 s $::: ::e} 149. Potassium permanganate KMnOd 845 11.85 w 900 11.1 vs 1725 5.8 w 150. 840 905 1625 3470 Calcium permanganate Ca(Mn03z.4HzO 11.9 m 11.05 vs, b 6.15 8 , s p 2 . 8 8 vs Potassium ferrocyanide &Fe (CN)8.3H20 10.75 vw 10.05 vw 6.13 8 , sp 6.07 m 4 . 9 6 vs ;:%} 154. Calcium ferrocyanide CazFe(CN)n. 12Hz0 1615 6 18 m 2015 4 . 9 6 vs, sp 3390 2 . 9 5 vs, b 155. Potassium ferricyanide KsFe(CN)e 2100 4.77 s 847 1333 1430 1575 1645 2665 2780 3450 Sodium cobaltinitrite NaaCo(N0l)s 11.8 s , s p 7.5 vs 7.0 vs 6.35 m 6.07 w 3 . 7 5 vw,s p 3.6 vw, sp 2.9 m 157. Ammonium hexanitratocerate (NHdzCe(N0dn 745 13 42 8 , sp 803 12 45 m, sh 807 12.4 8 , sp 815 12 25 vw 1030 9 7 s, s p 1050 9 5 vw 1260 7 95 vs 1325 7 55 w 1420 7 05 s 1530 6 6 vs, b 3210 3 11 s, b 158. 138. imp. = impurity Cm.-1 Microns I 151. Barium permanganate Ba(Mn0a)t 840 11.9 m , s p 877 11.4 s 913 10.95 s 935 10.7 m 156. vs, b m,sh s,sp m, b 750 940 1625 3450 10.75 s , s h 2.9 w 134. Zinc chromate ZnCr04.7HzO 720 13.9 m 795 12.55 s 875 11.4 940 10.65 1050 9.5 1090 9,l5 s,b 1183 8.45 m 1620 6 . 1 5 vw 1820 5.5 vw, b 2700 3.7 w, b 3450 2.9 s,b vb Cm.-1 Microns I 140. Calcium dichromate CaCrzO7.3HzO 725 1 3 . 8 vu. 830 12.05 m 900 11.1 m 940 10.65 s 1625 6.15 m 3450 2.9 s 141. Sodium chromate NaKrOd 14.7 m i?:: 11.2 vs 1410 1780 2000 2860 3070 3150 Ammonium chloride* NHiCl 7.1 8 , sp 5.75 w,b 5.0 vw 3.5 m ::?!} 159. Barium chloride BaClz.2HzO 700 1 4 . 3 vs, vb 1615 6.18 8 , sp 1645 6.07 8,sp 3370 2 . 9 7 vs 2918 2861 1458 1378 720 160. Nujol 3.427 s 3.495 a 6.859 m 7.257 m 13.89 w V O L U M E 2 4 , NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1259 one of the salt plates with a very thin layer of solid paraffin to The purities of the samples are indicated in the legends for the hold the particles in place (6, 7 ) . The fine powder may be precurves. pared by grinding, by evaporation of a suitable solvent (6, 7 ) , or Some idiosyncrasies of the curves warrant mention. Many of by sedimentation ( 5 ) . Vacuum evaporation which has been them show weak remnants of the carbon dioxide bands near 4.3 used for preparing films of ammonium halides ( I I ) , may be useful and 14.8 microns. The latter always appears as a sharp upward for other relatively volatile inorganic materials. pip. Many of the curves exhibit a drop in transmission near Spectroscopic Procedures. 8 1 1 samples were examined from 15 microns and then a small increase beginning at 15.5 microns. 2 to 16 microns with a Baird XIodel A infrared spectrophotometer. The initial decrease is due to the absorption by the sodium chloride Wave lengths are accurate to about zt0.03 micron, although for plates, which was not compensated in the reference beam. The broad bands the error of judging the center may exceed this. It reason for the later increase is not known, but it is not real. It was sometimes found that duplicate spectra for the same comhas the effect of suggesting an incorrect position for bands near pound differed by more than this amount. Some oossible reasons are mentioned below. Table 111. Infrared Bands of Various Nitrates (Cm.Representative ex a m p 1 es of Intensity m, s p a w m, sp w VS S S VS vw several ions were examined in .. , . 836 .. 1358 .. .. 1790 2428 the potassium bromide region 824 1767 .. 1380 , . .. 733 803 835 1318 .. with a Perkin-Elmer 12B spec, . .. 820 1044 (1359) ( 1430) (lii0, 737 .. 815 .. 1387 1795 1441 .. 2iio trometer. Likewise, a series of 729 .. 817 .. 1352 1418 1774 (2410) ten nitrates was examined in the (1785) .. 835 .. 1361 , . . . (1640) i6ij .. (807) 836 ., 1372 .. rock salt region with this same 836 .. 1378 .... 1587 1790 2431 726 807 836 .. 1373 , . .. instrument in order to fix the Bands >3000 cm.-L are omitted. wave lengths of absorption more ( ) Baird values, less accurate. accurately. a w, ni, s = weak, medium, strong. g p = sharp. v = very. No attempt was made to put the spectra on a quantitative basis. RESULTS 16 microns. For example, in ferrous sulfate heptahydrate The spectra are presented a t the end of this paper. Table I ( S o . 91) the curve indicates a band a t 650 cm.-l (15.5 microns), lists the compounds examined and gives the numbers of the corbut actually it is a t 611 ern.-' (16.5 microns). responding spectral curves. Table I1 summarizes the positions DISCUSSION OF RESULTS of the bands in wave numbers and in microns, and gives estimated peak intensities. If more precise wave numbers have been The spectra range in quality from surprisingly good ones, with determined with the Perkin Elmer spectrometer, they are used. sharp, intense bands (see curves for barium thiocyanate dihyAsterisks indicate those compounds examined in the potassium drate, No. 28; strontium nitrate, No. 44; and ammonium bromide region. hexanitratocerate, No. 157,) to very poorly defined ones such as The spectra themselves are shown in graphical form. Nujol those for potassium silicate, S o . 32; monobasic magnesium bands are marked with asterisks; portions of curves run in fluorophosphate, No. 69; and monobasic potassium orthoarsenate, lube are indicated by an F. The spectra of Nujol and fluorolube KO.75. I t seems to be characteristic of the phosphates, and are included for comparison (No. 160). I n a few cases the ponder especially of their monobasic and dibasic modifications, to have was used without a mulling agent; these are indicated by P. ill-defined spectra. The reason for this is not clear, but it may be due to lack of a single, well-ordered crystal c rn-1 structure. Effect of Varying Positive Ion. One of the purposes of this study was to ascertain whether the various ions have useful characteristic frequencies. It was therefore of interest to know the effect of altering the positive ion. The spectra of ten SUIfates are shown in Figure 1 in the form of a line graph. I t is seen that two characteristic frequencies occur, one a t 610 to 680 em.-' ( m ) and the other a t 1080 to 1130 cm.-l (s). There is enough variation between the individual sulfates so that it is often possible to distinguish between them from the exact positions of the bands. Table I11 presents similar data for ten nitrates. Again there are characteristic frequencies, a t 815 t o 840 cm.-' (m) and 1350 to 1380 (vs). The authors I have been unable to find any orderly relation between the positions of these nitrate bands and a MnSO4.2W property of the positive ion, such as its charge or I I mass. This is not surprising, for there are a t least ZrSO4.4W three reasons why a frequency may shift slightly as I I1 . I C r S 04' K2S 04 the kind of positive ion is changed. 24 W Figure 1. Comparison of Infrared Spectra of Ten Sulfates W. Water vh. Very broad s h . Shoulder The different charges and radii of the various positive ions produce different electrical fields in the various salts. These doubtless affect the vibrational frequencies of the negative ions. (Continued on page 1298) ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1260 IW /4n I I I 10 A~ Z;\ $U: z i 40 f~ 20 , ~ ~ 1 J ~I 2 500) 4 8 7 low Urn 2SW 5 6 I WAVE LENGlH IN MICRONS WAVE NUMBER5 IN CM' ,5WI,W ?OW I200 IIW ~ \ ~ Sodium metaborste, NaBOz ;I C.P. ~ I 0 I , F = bo W I 10 liW Iwo I1 12 I I1 1s I4 ' 0 WAVE NUMBERS IN CMI 9w aw b2S 700 Magnesium metaborate, Mg(BOz)z.SH:O C.P. 2 1 4 5 b 7 WAVE LENGTH IN MICRONS WAVE NUMBERS IN CM 5wo 100) Urn 2100 lwa Ism ,104 I I1W 9 I100 IO IIW Iwo 12 I1 WAVE LENGTH IN MICRONS 11 9w I4 WAVE NUMBERS IN CM' I00 IS 7w I6 b2S 100 lM Lead metaborate, Pb(BOdn.Hz0 IO IO 560 bO C.P 3 z g* 40 z 20 20 0 I 2 4 5 6 7 WAVE LENGTH IH MICRONS 8 IO P I, I1 I1 WAVE LENGTH IN MICRONS I4 IS I6 0 Sodium tetraborate, Na2BO. 10Hz0 C.P. WAVE LENGTH IN MICRONS WAVE LENGTH IN MICRONS WAVE NUMIRS IN C H 500) (ooo 100) 2Mo low ,5Wl,W 1100 IIW llW Iwa 9W WAVE NUMBERS IN CM1 ud IM 7w 625 Potassium tetraborate KgBdO?.5HzO IO c iz * z e 1" : 20 0 WAVE LENGTH IH MICRONS WAVE LENGlH IH MlCRMlS P. V O L U M E 2 4 , NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1261 IW 80 1 I . E i ZbQ I z I! r " 10 1 1 , C.P. M) * Y ~ v 20 0' I IW. 4 5 8 7 b \l/*la/ !1 s I 11 IO 0 1 10 II 0 11 I1 I4 I. I5 IO V " l * j I V ilo 1 '1'"Sodium perborate, 60/ r I ?;aBOa.lHdI Y E'O ' I 'I 10 s5 Manganese tptraborate, MuB4&.8HzO 6'* j II L' f, '0. 1 I I \AIL I I I ~ ~ I 1 6 7 1 I V (0 * I ~ :L/; I C.P. lh/--, I ~ 10 I I I I l l I1 I I1 I1 10 0 I5 I4 Ib Boric acid, HiBO 02. SVX 100. Y IO 1VX 4oW . < / ZSW 1VX r F ! z p7f ' IIW l u x ) . Q' 1 100.' 1 / I 1 4 5 b -#-10. H F fa- zi 615 loo 7m 10) - 'm * I 10 I I 7 I5W J I lux) 1lW 9 1100 1100 10 11 IVX I I1 I4 700 iw (w I5 Ib 615 1'0 i V I AR u 64 40 lo 8 0 9 0 I Lithium carbonate, LizCOa IO I ~ 1 Pure M I \, i *- Boron nitride, B N 9 1 1 ~ 9w * I 10 loo0 I ~ Y liW uI 'Ob Y I IlW / c L c 1100 I1 I1 I IS Ib ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1262 WAYL NUM?ERS IN C M ' 5ccO wO 3w0 15W iico 1 5 w 1 4 c a 1100 lw(. WAVE hLM5ERS Ih C U I iom )loo FCO 100 6CC bli Sodium carbonate, NazCOi AR Potassium carbonate, KnCOi AR Magnesium carbonate, basic, 3MgC.01Mg(OH)n.aHnO Unk Calcium carbonate, CaCOa AR 5wO u40 1wO 2m ISWilW 1004 I700 IIW ll00 I IW IOW 9w IW IM 7 80 ! J I b15 15Im Barium carbonate. 3 r BaCO: -80 AR " 5.f Y I ~ 1" Y 10 --~ - * 1-1 I ! 10 41 b 1 5 L WAVE LENGTH IN MICRONS 1 I V 0 I I 1 I1 WAVE LENGTH IN W C R M I S 10 I5 b0 V O L U M E 2 4 , NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 I,263 WAVE NUMlfRS IN u ( l WAVE NUMBERS IN C M ' 5 io0 Cobaltous carbonate, COCOl W Unk. m 1 1 5 b I WAVE LENGW IN MICRONS I 11 I1 I1 WAVf LfNOTH IN MICRONS 14 16 0 lb Lead carbonate, PbCOj Unk. Ammonium bicarbonate NHiHCOa Sodium bicarbonate, NaHCOa C.P. Potassium bicarbonate, KHCOI C.P. ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1264 IW I I i Sodium cyanide, NaCN 80 I 'Na,CO. - k. NaaCO3 impuritg W I 40 P 20 20 I 0 I 0 Potassium cyanide KCN IlHCOa and K:COa impurities Potassium cyanate, KOCN Considerable KHCO impurity Silver cyanate, AgOCN "Higheat purity ' I IW1 \ IO s I mPY- I,/ fM ' Ammonium thiocyanate, 2 5 1 m 1 " AR 'D F c E" 10 E 1 10 1 10 I 0 1 1 ' 8 WAVE LENGTH IN' MICRONS e 10 I II I1 WAVE LENGTH IN MICRONS 14 0 5 NHaSCN 80 \ I I 2 1 I -7 Ib V O L U M E 24, NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1265 Sodium thiocyanate, SaECS Potassium thiocyanate KBCS AR WAVE NUMBERS IN C M ' XCC IW Urn 3wO 1SW 3000 ISW I4W 12w IIW I W Iwo 9w WAVE NUMIIERS IN CM 8W b25 IW 100 IO (0 M (0 Barium t h ~ o c y a n a t e Ba(SCX):.2HzO C.P. i f e 4 5" $ 10 20 0 0 3 1 sox 4ccc 1 3mo 25w 5 h 7 WAVE UN6TH IN MICRONS WAVE NUMBERS IN CM 2000 I5W 1 l4W l3W V 17W IO W IWO I! Vw I2 I3 WAVf LENGTH IN MICRONS I4 WAVE NUMOERS IN CM1 8W lb bl5 lW 703 lW 1- Mercuric thiocyanate, Hg(SCS)* m (0 Pure (0 4 I" Y 20 10 0 0 3 2 SWO 4 IWO 4wO ISW 5 6 7 WAVE ttNGrn IN M~CRONS WAVE NUUBERS IN C M ' lD00 1503 I+W V IIW I1W I 0 w lax, 9w It I3 W A S Wlli IN MICRONS 15 I4 WAVE NUMBERS IN C M ' SOD 7w Ih hl5 -01 lop Lead thiocyanate Pb(SCN)* m IO 3 C.P. kt4 n < rm 4Q v 20 0 1 I 5 L 7 WAVE LENGTH IN MICRONS V IO I1 I1 11 WAVE LEN6TH IN MICRONS Ib IS Ib 0 ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1266 Sodium metssilicate, NarSiOr5HaO O.P. Potassium nietrtsilicate, KrSiOi O.P. Xm IW Io. 1800 u*yI 1100 I 1 100 Irn 110) Ilm la4 no rr-"---/ * J W 7 8s " Iyo lOm 1W 800 (11 Sodium ~ i l i r o f l ~ ~ o r i d ~ , 33 \ SazSiFe w a.p. ?- I I' 1 L * W 1 44 20 20 ~ 0 0 3 I I 1 b WAVE NUMBERS IN 8 7 0 I1 CM I ll I+ I& Ib WAVE NUMBERS IN CMI Silica gel, SiOmHrO WAVE LM6W IN MICRONS WAVE U N 6 W IN MICRONS 5 IW Sodirim nitrite, NaNOi H 44 10 0 2 I I 5 WAVE b LWOM IN HICRM 7 I * 0 II WAbl IuN6W IN I MCRONS 3 4 It 4 b C.P. V O L U M E 24, NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1267 Potassium nitrite, KXO, C.P. tm ' I -. MI 3 f 1I * w C.P. L Y I * ~ fi I 1 2 \ Y / I 20 37IW Mver nitrite, AgKOz / 1 I 4 la 20 0 e 5 6 7 WAVE LEWTH IN UlCRONS IO I 1 2 WAVE LENGTH IN WCRONS 14 I5 WAVE NUMBERS IN CM I WAVI NUMBERS IN C U I Ib 5 Barium nitrite, Ba(N0:hHsO 80 C.P. Y a 20 2 1 5 6 WAVE LLNGTP IH H U M S 7 I e 0 IO II I2 WAVE ENOW IN I1 mcRoNs I4 I5 Ib 5 im Animonium nitrate, NHaKOs W C.P Y 20 2 I I 5 WAVE UNOIH b m 7 MICROHS WAVE NUMBERS IN C U I IO II 12 I> WAVE LENOM IH MICRONS I4 Ib * WAVE HUMBEIS IH C W Sodium nitrate, KaNOa AR a WAVf YHCM IN MICRONS ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1268 5wO W UDO 105) 2SW 2mO z ll00 IXd rn im , b25 700, , loo l P \ w d '4l Io // 1' 60 IlW llm 1100 l4M I z A 11 I 1 bo/ ; g S Potassium nitrate, KSOa M 1 ' 401 * e 10 I I 10 I 10 0 1 1 I 5 b 7 I 0 I 1 1 I IS Ib * Silver nitrate, AgSCs C.P. Calcium nitrate. Ca(Pi0dp C.P Strontium nitrate, Sr(XOd3 Unk. WAVE WUMlERS N CM 5 100 (D 10 10 1 1 4 5 b 7 WAVE LENbTH H MICRON5 I 10 It I1 I1 WAVE LEN6lV IH MICRMIS 16 IC 1b * Barium nitrate, B~.:(?jod? A It V O L U M E 24, NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1269 Cuprio nitrate, Cu(XOi):.3H:O C.P. Cobaltous nitrate, CO(;203) 2.6 €I20 AR Lead nitrate, Pb(XO3) AR 100. IW 80 ~ z 2 bo- i9 20 0 2 no ~ i' 3- \r' AR I / P Ferric nitrate, Fe(S03)3.9H20 *7 49 " - ' \ / p z i t 4 , 4a ~ " ' W A d LENGTH IH' MICRONS 20 a I V 0 I 2 I3 WAVE LENGTH IN MURCUS 0 Ik I5 Ib Bismuth subnitrate. BiOSO3.HnO Unk. ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1270 IW 80 5 EM I '0 / I F \J 1 \ " I s f Y I I \ ! I 1 1 5 M Mo( I w - ' I ( " ' 3oW , 2'W' ' 1 I v i v t I D * 3- ji ! L:j lol 0 ~ 2 I swo k4f8 IW 80 ' !' 5 10 V * 0 2 3 I , 0 I4 IS Ib i 52lw ; 2100 zoo0 lua Ism I2W IlW IlW IO Imo 11 c. P I I 40 I20 i I1 I2 /--.., b25 700 I I 153r I J i I i? ba I I I I 8 . C.P. 4a I ! Magnesium phosphate, tribasic, Mga(POdyAHz0 I8O , I ~1 t 5 b WAVE LEN6TH IN MlCRMiS ' 0 15 I* aw (00 I -$ ! I e 8 Potassium phosphate. tribasic, &PO4 10 I IC/ I 7 b I; I P 1 I I :i I I I I2 I1 WAVE LENGTH IN WCROHS I I f Z" l \\ j 'A P g, g I1 l I b-,* ?I I \ :1* 1m " . 4a I ! * /I a- 1 I'\ W \ I I i \ I I 80 b4 20 I I b 7 W A M L W l H IN MICRONS I AR / ( 1 1 10 0~ 2 Eodium phosphate, tribasic, NalP04.12H;O 51: I IO 0 0 I1 I2 I3 WAVE LENOW IN MICRONS Ib Calcium phosphate, tribasic, Cas(PO4)r r.e Manganese phosphate, tribasic, Mni(POdp.7H10 C.P. V O L U M E 24, NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 Imp 1271 WAVf NUMBERS IN CM1 WAVE NUMltRS IN C M ' m tmo 2100 Ima IW I- IZW IIW I IN tW imp iim I IW / ir\ 7 1 . m ., , , qoo LIS 5 I I ! I i i ~ l Nickel (ow) phosphate, tribasic, Nia(POdz.7 H?O - 1 / * , I I * /, 1 I \ \, L, I I I , I 7 I I I I I ; I I 0 Copper(ic) phosphate, tribasic, Cut(POa)z.3H10 C P 5wO ION IWP 25W WAYZ NUMBfRS ZOW H CM 15w Iuc Lm, 1100 lIW Iwo WAVE NUMBERS IN C M ' 9w 100 IN b15 phosphate, tribasio, 58Iw Lead PbdPOdz IO I C.P. I? I I ~ ' i* 10 I 1 . I 5 b 7 WAVE LENGTH IN MICRONS I V 0 I 12 I1 WAVf LENGTH IN HhROlll 0 I4 I5 Ib WAVE NUMBERS IN CM 5 iw (0 Chromic phosphate, tribasic, CrPOc.Hn0 P.P. M 40 20 5 b I WAVf LfNGTH IN UICROM I V IO I1 I1 I> WAVf LENGTH IN MKRONS 0 I4 I6 Ammonium phosphate, dibaaio, (NHOrHPOt C.P A N A L Y T I C A L CHEMISTRY 1272 WAW W W S IN CU- l5a IUD I1rn I200 llrn WAVE NUMDERS IN C U I 700 100 Im, b25 100 100 S 80 Sodium phosphate, dibasic, NaSHPO 1.12 H20 C.P. U E I" 4 P n 10 I 1 I 4 I I 5 b 1 WAVr W T H IN UCRONS I 8 IW * I I 10 I1 I 1 I2 I1 WAVr LW6W IN MICRONS I I I4 I5 Ib Potassium phosphate, dibasic, K ~ I I P C I (0 C.P. E M f o4 F 20 0 WAYS W T H IN MKRONS WAVE ENSW IN UCRCUS llagnesium phosphate, dibasic, MgHPOa.3HzO C.P w urn Irn 1m 2x0 WAYS NUMBERS IN CU I WAVE NUMBERS IN C U I 2wo 5 ID3 10 Calcium phosphate, dibasic. CaHP04.2H20 m C.P jM f Lo 5" 4 10 20 P 0 2 5 6 I WAVE UNSW IN UKROM 1 8 * IO 0 II 12 I1 WAVE LENGTH IN MICRONS I4 I5 Ib WAVE NUMllRS IN C U I Barium phosphate. dibasic, BaHPOi C.P. 1 a 4 5 b 7 WAVr LBTW N W W 8 * IO I1 I1 t i WAVE LWSM IN MICRONS I4 I5 Ib V O L U M E 2 4 , N O . 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1273 IW phosihate, mono67lW Sodium basic, KaH1POd.HsO ~ IO ao kb3 n 5 F lJ ~- 5 a8 t I F v I 20 . I 0 2 I In -v'd 20 I L 7 1 1 I 9 I I * I lW - 68~ .- \J * I 0 I P 2 5" 1 i0 I IO 20 a 1 I 5 \ ia w I IW z C.P 1 I 1 I Potassium phobphate, monobasic KHlPOl C P IbO i*) 10 1 I 0 2 3 4 I b 1 WAVE UNOTH IN *UCRON5 8 v 0 It 2 3 WAVE UNSTH IN MICROM 0 I4 16 Ib .\Iagnesium phosphate monohaeic, 3Ig(HzPO& cC . P. P. I 0 2 I 4 6 b 7 WAVI W ? H IN MICRONS 8 ID I1 I2 I3 W A X M O T H W MICRONS I4 IS Ib Calcium phosphate, monobasic, C a ( H ? P 0 3 ~ . H r O .\ R ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1274 Sodium rnetaaraenite, YaAsOe AR I I IWW( I I 1 72O0 Ii Calciuni orthoarhenate, tribasic, Cas(AsOd2 to C.P. M 4a l, \ / f/ XI 0 3 1 4 5 b 7 WAVf LfNGTH IN MICRONS I I ID 12 I1 WAVE LLNGTH IN MICRONS I IS I4 Ib Fodiuni orthoarsenate. dihaiic, Na:HAsO~.iH,O Unk. Lead orthoaraenato, dibasic. P ~ H A s O I C.P. WAVE NUMPfRS IN CM X48 1000 *Dp 2100 IWO Sm 110) Ilm ,100 llm Imp 9m W A M NUHIILRS IN C H I UD 7m bZS Im P o t a w u r n orthoarsenate, inonohasic, KH14a04 iR M 4a m 0 2 3 4 5 6 7 WAVE LENGTH IN MICRONS 8 10 II I2 I3 WAVE LfN6lH IN HKRONS I4 I6 Ib VOLUME 24, NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1275 Arsenic trioxide, .-\sr03 Vnk. Yodirirn 1276 ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY Potassium sulfite. K?S0!.2H?0 r I, Calcium sulfite, CaSOi.2H20 C.P. Barium sulfite, BaSOi C.P. Zinc sulfite, ZnSOa.2HnO C.P Ammonium sulfate, (NHWOd Unk. 1277 Sodiuiii sulfate, Xa?SOd AR Potawlurn sulfate, lid304 AR Calcium sulfate CnS04.2H20 AR aiilfare, JInSOc2HzO XIangnn-e C.P. ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1278 Ziroonium sulfate, ZrEOi,4H?O i I BO C.P. ~ d , , I I oi * I ~ I 1 1 rJ I 20 I j ~ 6 7 I 9 IO j I I I, 12 ~ 5 , I ~ i 0 13 k 15 Ib fii ! IO g i 5 bo; * \ 10 z l 20- ol ,I I 1 * I I ' i i : 1 bo i ; . j ~I ! I I __r ~ f~ 5 J 110 I I 5 WAM tEwm b 7 IN MICRONS : j" 1 i 0 Unk. i , " 0 _ , V Chroiniu~npotassium ralfare, CI.E(SOI)J.lirR0~.24H:O I1 I ,I WAVE LENGTH UI UICRONS IC I I I I, I5 1 10 I6 Ammonium bisulfate, NH4HSOl C.P V O L U M E 2 4 , NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1279 Sodium biaulfate, XaHSOI AK Potassium bierilfate. KHSOI AR Aiiiruoniurii thiosrilfate ( N€i,)..S2OI C.P Sodium thiobulfatr, xa:S*03.5H?o .IR Potassium thioniilfntr, KnSrOa.Hr0 C.P ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1280 I1100 IHD 31100 k1100 IW WAVE NUMBERS IN CM 2Wa IHDiHiO ,IS0 l1W two ilW PW W A M NUMBERS IN CM BOO 700 b2S IW I I I Magnesium thiosulfate, hlgS20a.6H10 C.P. Barium thiosrilfatr, Be&Oa.H>O C.P Sodium ~netahisrilfite, Wa?PtOs Potassium nietittiisuifite, Ii2SnOr AR IW, Arnmoniuni persillfate. (NHI)?S~O~ I - IO 4 1 .IR 1~ !bo7A 5 E 10 V 20 +i I , * i I ~ \ m I I 4 1 'il , 5 b 1 8 j P O 0 II I1 I I4 I5 Ib V O L U M E 24, NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1281 Potassium persulfata, KnStOs C.P. Sodiiini selenite, Pl'alSeOd Pt i y e IW i I Y A 5 M I 40 Vnk. I I ~ I 1 20. , \ ,I 4 I 20 \/ I i I I 0 I a \ I ~ $ (0 \ t \ / z 5 selenite, 'I 08ImCopper CuSeOL2HZ0 I Y *? A 0 1 I 5 b 7 8 V 0 II I2 I3 I4 IS I6 Sodium selenate, SazSe04.10H~O C.P. 1282 ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY rKa urn ma WAM NUHBERS IN CM' WAVE NUUlKRS IN C M ' 1XD mo b% 100 ,Cd 80 Potassium Belenate, KzSeOi W C.P. 60 4 20 10 0 1 1 4 5 b 7 W A M LENCTH W MICRONS 8 IO I1 I1 I3 WAM LENSTH IN MICRONS I4 I5 Ib 0 Copper selenate, CuSeOc5HzO C.P. Sodiuiii chlorate, liaCl01 AR Potassium chlorate, KClOa AR Barium chlorate. Ba(C10a)z.HaO C.P. V O L U M E 24, NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1283 WAVE N V H l E R S IN C U ' W A S NUMBERS IN C M I 5 IW 80 L.P. M 4c 20 0 I 3 2 5mo IW ImO UC4 I= 1 $10 8 L 11m 1100 Iom I2 I3 W A M LLHSTH IN MICRONS m 10) sw 8W I4 16 I6 I & 11 11 ;ir 2 lrn 14w II IO \n,.L'-\, * f"" 1 ',ii s$ * I 7. lrm 2mO 1 p?, IO 5 6 WAVE LENOTH IN MICRONS I I I I LJ x 10 t 0 ym 1w- urn 3om 250) 2om ? 1 150) , 14w I 13W l l la I , l l IlW ImO > ! .I 80 :/ , , , j I 7w d )IS i IS'* I 80 AR ! 5 b0 n I # 2Z W i I Y ' I 0 2 \, I I 3 S 7 b I 0 9 IW ~ ! P r rL 0 I2 I1 87 ' ZW 2 1 10 I . I nf V / I\ i 11 1 \L i 1 I I I 2 3 4 S b 7 9 IS 1 r' 1[ I 1 / Mgd104 11 1191 10 I , h ~ I1 I 1 I I 0 Ib -lW I I , /* I - ' I 10 I 02*+- I 0 I4 I /?\ I d* 02I+! 11 I 10' ! I - 1 1 I ; l 1 ?r , IO bo I z 2 I3 I lo I+ IS Ib ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY Potassium bromate, KBrOa hR Silver bromate, AgBrOi C.P. Sodium iodate, KaIOz C.P. I 10 I9 0 0 I I 4 6 b I 7 0 I1 1 I I, IS Ib Potasaium iodate. K I O i Unk. Calcium iodate, CaIOa.BHz0 O.P. V O L U M E 2 4 , NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1285 Potassium periodate, KIO4 C.P. .4mmonium metnvana. date, NHcVO: c. P Sodiurn rnetavunadate. SnVOz.IHr0 Sodium chromate. KaL'rO4 ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1286 ym urn 3m0 Ism WAVf NUMBERS ZmO M CM' IUD ,100 1100 Im I200 1100 I wo ImO WAVE NUMBERS IN 800 \ 'rlV$ -I !5 ** z 1m b2S IW I IO Potassium chroinate, KnCrO4 I + ~ rA ; \\ P, I * I W i 9,' I I 20 I * 0 I CM' I 3 I 4 5 b 7 8 I IO I //J O I 10 W' ,I I1 I 0 I I4 I5 I 1 Ib l l a g n e j i u n i chroniate, f iiii i I\ I MgCrO~.iH~O 10 C.P. Barium ciironiate, BaCrOa C.P. Zinc rhromate. ZnCr04.7IipO C.P. WAM NUMBERS IN C M ' pm WAVf NUHIERS IN 8W CMl 1m V O L U M E 24, NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1287 136 Aluminiini chromate, Alz(CrO4)i M I I C.P. 1 1 I S -/I , I I I oI ,' 3 , m>YE Wr(0 im 1 0 8 5 1 7 WAVE W T H IN MICRONS nm IUD t I, lua Ilm 110 IlW 10 I !/ lmo em Ho 625 7m I 37' l 'V $ f j F I ~~ ~ I 1 10 I . 0 3 8 - I , 0 . 2 I1 I1 I3 WAVE LENGTH m WCROHS I 40 m b Sodium dichroinate, NatCrtO; .2€ 1 2 0 I38 W C.P -c I Y IS I4 \ I 1- / rl i i'L d t 44 m IV I , I 0 5 b 7 WAVE W T H IN MICRONS mnm uyx)uDo IO \ 20 I * 7 7T 1 - 1I I !\! !/[ - I !/ \1 I ,VI 0 5 b 7 WAVE LINGTH IN MKlOHS IO iM \r I C.P. S I ' 100 i : \, d i I I Ammoniuni dichroniate, (XHi)zCrSO; 80 1 ~ I b I5 4 WAVE LENGTH IN MICRCUS 1 < S ,I 0 I z IO I I WAVE NUMBERS H laa I 0 II I I1 I I4 Ib WAVE LEN6TH IN MKRONS W' IUD 9 1100 im iim WAVE HUMERI IN W1 iiw ID^ ua m b15 700 im IC4 M W Potassium dichromate. K~CTSOT L-nk. i fbQ M ;;" 40 : Y m 20 . 0 I 3 row urn nm 0 5 WAVE UNOW b 7 IN I ~ O N S WAyt NUMlERS IN C Y ' IUD Imo IUD iua 9 8 iim IIW itw IO imo I1 I1 I3 WAVE LEMGTH IN MKROM WAVE NUMDERS IN C M ' 9m em IS I4 7m Ib bl5 Calcirini dichromate. CaCrzO;.SHrO C.P. 1 O I *Y I II 4 I 1 5 WAVE LINGW 7 b m WRONS 8 * 10 I1 I1 WAVE LENGTH IN MKROHS ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1288 IW ~ I4I ~ P i 1 Copuer dichromate, C uCr& .S H 2 0 II S 110 i P. \r A m~ I 5" $ 1 I I 1 I 4a I I I 10 M I I 0 S 4 7 b I 9 IO I I 10 I/ ,I . I 1 0 I5 Ib >odium molybdate. SaAfo0~2HzO .4 R Iopdurn -2 lwo ludm Iffl AT M P I $@ M I * I / Z" \ !~ : Y 20 C.P. i ~ I 2 P molybdate, I 43:Im Potassium KzMoo4.mo 1 i \J I I P f 10 I '10 ~ O 1 I 4 ' -" . I S b WAE W T H M UCRONS l o 8 9 0 ,I 1 I1 WAVE LENOlH IN W C U S I, IS b ,4z .4 m nion u ni I \ / W / s F 53 -,pf, J M I" he1)tamolybdate ~NH~)s~Io;Ou.4HiO - x U I .1R 4 10 10 0 0 1 1 4 5 b 7 WAVE LENOM IN MICRONS 8 V IO ! 1 1 I. I5 I6 WAVE LENOW IN WCRONS WAVE NUMBfRS IN C M ' 5 lm Sodium tungstatr, S~~WOL~IIIO (0 c P. M 10 1 I I 5 b 7 WAVE LEN6M IN MICRONS D . 0 ,I WAVE I 1LEN6TH 111 11 MKRONI I. I5 Ib 1289 Potassium tungstate KzWO4 C.P Calcium tungstate Caw04 Pure WAVE NUMIIERS IN C M ' 15% I100 I1W IM IIW em Iwp .. WAY€ WMERS IN CMI 800 '15 7m I I ' -,i \ ,~ ', I48 ~,-.-- I4 ? ~ Sodium permanganate. NaMnOc3HzO C.P bo ' 1 "i,: I * f - i I 10 ;, W 1 0 3 1 4 I 5 6 7 WAVE LENGTH IN MICRONS 9 IO WA- WAVE NUMlElS vi C M ' yxxl Mm UD) IW 1m 2mo lxx) lux) llm ,100 IIW Imo .m I3 I2 I 0 I4 15 W l H IN Y C I C U S b W A M NWlERS IN W-l 7m 8rn b25 im 10 I4 E 5 AR = 60 M 4 - 5 Potassium permanganate, KhlnOi 40 10 P 10 20 0 1 4 5 b WAVf LEN6TH IN MICRMIS 7 8 1, 11 11 W A M LWOTH IN MICRONS I. 0 I5 Ib Calcium permanganate, Ca(MnOa)z.4Hn0 C P ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1290 Bariuui permanganate Ra(3lnOi)z C.P. Sodium ferroeyanide, SaiFe(CN)s.lOH.O C.P Potas.ium ferrocyanide, KqFe(CX"i).3I1~0 hK sbx rom ' rn 2rm 15m - Im 10 \ f n Ef M I E II \, 4 110 Pure i~ 60 10 I ,I * IO IIO I I l I 0 I 4 Ca!cium ferrocyanide, CarFe(CN)s.l2H>O I54 I I J I I I J 5* I I I 5 b 7 I O 9 0 I I1 ,I I, I5 Ib Potassium ferricyanide, KsFe(CN)s AR V O L U M E 24, NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 5WO IMo 1wP 2x4 WAVE NUMBERS IN C M 1 1x4 I r n 1wP I1W 1291 IIW IIW WAVE NUMBERS IN C M ' lca aw VW 615 7W Sodiuiii coliultiriitritr NarCo iSO.!* f- ~ I 1 I 1 LO 1 - % . K I I I I i 1 I I 157Iw r-\ I I 'e I ~ 10 AR Barium chluride, BaC12.2H10 .i R ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 1292 Table IV. 1.0 1 Eniiwion Sa I.; Ca To explore this possibility, u series of eight synthetic mixtures wa? prepared and analyzed independently by the three techniques. ( A photographic x-ra!. procedure was used.) This iriformation was then pooled, thr data were re-esamined, and ii combined analysis was obtained. The test was not completel!fair because it, was known that infrared spectra have been ohtained for nearly all the inorganic salts in the laboratory, and that t'hese same salts would he used in making up the mixtures. I n addition, t,he components n-ere mixed in roughly equ:il amounts by bulk. The results are shoa-n in Table IT'. The analysis of misture 3 is discussed in greater detail below. I t is apparent that no one of the techniques by itself is powerful enough to give a complete analysis of even these idealized unknoums. This is partl)- because there was no prior information about the caontent of the samples, and therefore every possibility had to be considered. -1s xith any other anal) much more detailed and reliahlr Use of Infrared Spectra in Qualitative Anal>-sis Independrnt d n a l y - e . Infrared SaHCOi Final Cornbined rinalysis X-ray Actual Composition WaHCOi CaCOr KSOi NH4NO.I SO,--Silica eel 4T14SOI Very poor pattern B Silica gel .II Ph x Yellon 4 I'ellon- Na ICKr20; K N a S C S or N H i K S Cr Ifp(cloi)? Sulfide odor Ph Y Cd SiL?HlOi Bi B Sa AI K*CI.yOi NaSCN AIg(ClO,)?" Pb 1 Sothing Very poor p a t t e r n KilCrzOi S-aSCX RSCS CaS0. L H j O NazBIO; 10H?O CdS SaBiOx '! SatBaO; IOtLO CdS ') c ?P .\IO Ca I.; S a '? Sr 11 K*S?O6 CaCOa PhCrO4 KazSOr Y Caar PO, I 2 Sh Si P ca C P? Ba Na I. .11 ? SI.? 7 KaI.03 Ba(K0s A nitrate; prohahly BaPhSOI '? isos)?.possibly SaSOz Other component(s) Possibilities: Another nitrate, SaBrOl. Sa?WO, or K?\VOi. S a l l o O , or K l l o O ~ Changing the positive ion may produce a different crystallin? arrangement, resulting in a different symmetry or iiitensity of the electrical field around a negative ion. A difference in t,he type or extent of hydration probably alters some of the frequencies. Cm-1 700 600 8 BO; 840: 3 c coj a nco; 3 SILICATES N NOi NO: 900 1100 !OW 1200 Z 4 s Y soq ¶ *A L l 1 - II L nso; 3 5 ClOi Br Br 0; I lo; v voj c, c,o; GE .o= ! * s i - k l i I -1- 1 3 4 I 3 3 2 8 , 5 A 4 600 Figure 2. 700 800 900 1000 1100 IPW 1300 1400 Characteristic Frequencies of Polyatomic Inorganic Ions m, w. Strong, medium, weak sp. Sharp s. - L *LP No h b o i 2 w wo; 3 Mn MnOZ - A s20j 2 szoi 2 se sao; 2 s*o; c uo; A , 1 IO s20g - + NH; 17 P Po: 9 HPOq 6 H PO' 5 2. 4 5 SO; 6 1400 1300 -21 SCN' the other hand Hunt, J\-isherd, and Bonham ( 5 ) found that for anhydrous carbonates there is an approximately linear relationship between the wave length of the 11- to 12-micron band and the logarithm of the mass of the positive ion(s). Hunt has kindly pointed out that, the authors' data tit his curve, with the exception of lit,hium carbonate. Characteristic Frequencies of Inorganic Ions. Just as with sulfates and nitrates, most other polyatomic ions exhibit characteristic frequencies. These are summarized in Figure 2 . It is evident that they are distinctive and that they do not have a great spread in wave numbers. Qualitative Analysis. The usefulness of these charactei,istic frequencies in qualitative analysis is obvious. It appeared that the infrared spectrum might give, rapidly and easily, some information about the polyatomic ionE that are present in an unknoivn inorganic mixture. If only one or two compounds are involved, it might, even be possible to narrow the possibilities to a fex- specific salts. It also seemed that a combination of infrared, emission, and x-ray analysis might be very effective. Presumably emission analysis would determine the metals, infrared would say something about the polyatomic ions, and x-ray analysis might, give their combinat,ion into specific salts. 011 800 3 * In most, but not all, examples ** Literature value V O L U M E 2 4 , NO. 8, A U G U S T 1 9 5 2 1293 results can be obtained if there is some advance information ahout the nature of the unknowns. However, Table I\- also shoTvL: that the three techniques are nicely complementary, and th:it together they are capable of providing a considerable amount of information even when such prior knowledge is lacking. Although thrre are two or three surprising errors in the combined :inaI?ws, the over-all rwults are verj- encouraging. It is espec-iall:. noteworth>-that the actual chemical compounds are giveir iri miny ca.vs. WAVE N U M B S IN CM.1 15W1400 1100 1100 IIW 1000 tain possibilities for the x-ray analysis which greatly simplify its interpretation. The advantages of this physical analysis include small sampk requirement, reasonable time, and the ability t o determine the actual compounds in man>- cases. I t is evident, too, t'hat any or all of these three techniques are valuable preliminaries to a ishemica1 analyis on an unknown material, especially a quantitative one. Variability of Spectra. It is not uncommon to find that the spectra of t,wo samples of the same compound are somewhat different. There are several possible reasons for thin. In the spectra of sodium IMP~RITIES. cyanide, potassium cyanide, and potassium cyanate (Xos. 21, 22, 23) bands have been marked that are plainly due to 60 the corresponding carbonates and bicar2= bonates. CRYSTALORIESTATIOX. It is well knonm that the spectra of anisotropic y crystals depend on the orientation of 8 the sample. Consequently it is desirable io t o have completely random orientation of the crystallites to avoid such effects. This is an additional rewon for grinding L p d 0 the sample very finely. I5 Ib 8 9 IO 11 12 I3 I4 WAVE LENOTH IN MICRONS PoLnioRPmsai. Different crystalline forms of the same compound are often Figure 3. Portion of Infrared Spectrum of Lead S i t r a t e raDable of eshibitine slightly ., . different infrared spectra ( 2 1 1.. WAVE NUMBERS IN C M ' \ . A R Y I S G DXGREES O F HYDRATIOX. 1200 1100 1000 900 800 ~ t> 8 I -4 0 IO II WAVE LENGTH, Figitre 1 . I n vier\ caw 12 I 2 5 y , I3 1.1 Znonialous H a n d in Unknown 3 (:a301 .hould be w r i t t e n C a S 0 ~ . 2 A ? 0 Isi)i\-ii)i..ii, Ti:i.iisrui I.>. S-I,:~?. :in;ilysis of a conipletely o i r i i ~ \vhi~11 ~ thrr(J art' nlow than two unknowi sani~)IeI ~ ~ ~ i ~tiiffii.ult coniponc~ntr. It is not :i1)plii,:iI)lv t o noncrystallinc material.. ( r f . unknown 2 ) and runs into troul)lc \\-ith substances that gaiii 01' lose water of hydi,ation readily. I n both c5ase.q infmred i i often a rcliable tool. Suhstanc~eslike metal osides, hytirosides, and sulfides gener:illy h:ivcl no sharply defined infrared absorption from 2 t o 10 i d e from possible water and 0-H bands. On the ot1rc.r y are often good samples for x-ray analysis (vf. cadmium sulfide in unknown 4). The principal fault with emission analysis is its great sensitivity : it is frequently difficult t o distinguish between major components :ind impurities. This fact arcounts for t,he surprising oversight 01 cdcium in unknoivn 2 , and tungsten in 8. Infrared examination has advantages over wet chemistry for detecting the more unusual ions, such as BOz-, B407--, SzOs--, and S?Os--, since these are not included in the usual schemes of The proper sequence in using these techniques is the order cniission, infrared, and then s-ray. The first two present rer- Several esamples of variable spectra have been otiserved, lor Lvhirh the muse is not definitely knonn. Tn-o different samples of potassium metabisulfite, KzS206,were esaniincd, and proved to have different, patterns of band intensities in one region (see curve 104). I n potassium carbonate there is a hand a t 880 c m - ' or a t 865 em.-', and in one spectrogram out of a total of ten hoth hands appear. There is no cleai correlation b e t w e n position and water content. Figure3 shows that the mode of preparation is important. It rompares the spectra of two lead nitrate samples, one prepared nornially with Sujol and one with very little Sujol. Differmces near 1300 rm.-l and 880 t o TOO cm-I are striking. This may be an orientation effect. X more baffling case of unexpected variation was ol)serveil with unknon-n S o . 3. In analyzing this by infrared, calcium sulfate dihydrate was missed completely and magnesium percahlorate \\-as reported in its place. The reason is brought out in Figure 4. Pure calcium sulfate dihydrate has a single broad lmnd centered near 1140 cm.-' (8.8 microns), whereas in inisture 3 a strong doublet was observed a t 1080 and 1140 cni.-l Thtx origin of the doublet was puzzling berause no other ($omponcnt of 3 but calcium sulfate has a band near here. Calcium sulfate dihydrate had been run as a Nujol mull and mixture 3 as a dry powder. Reversing each did not change their spectra. Then calcium sulfate dihydrate was mised with each of the other components in turn in the dry state, and the mixtures \wre es:mined as Nujol mulls. It \vas found that the misture with ium thiocyanate gave a doublet. \Tith sodium thiorj-anate there was also a doublet, but it TI-as much less pronounced. It seems unlikely t,hat a chemical reaction between calcium sulfate dihydrate and potassium thiocyanate could account for these peculiar results, bemuse the materials are in the solid state. Two other possible causes are changes in crystal structure, presumably caused by changing the hydrate, and an orientation effect. The following observat,ions seem to rule out variable water content as a cause, and suggest the orientation effect. A calcium sulfate dihydratepotavsium thiocyanat'e mixture heated a t 170' C. for 3 days gave the two bands near 1100 em.-' Only one band was found after the salt plates were separated and t h e mull e ~ p o s e dt o air for an hour. A N A L Y T I C A L CHEMISTRY 1294 Another portion of the same heated mixture was esposetl to air under more humid conditions for an hour and then mulled in Nujol: two bands again resulted. This mull was opened to the air for an additional half hour, and only one band was found. \\-hen calcium sulfate dihydrate alone was heated overnight a t 170" C., three bands were found. The sulfate vibration absorbing near 1100 cni.-l is triply degenerate (12), and this may be a case of splitting of the degeneracy as a result of altering the crystal symmet'ry. Finally, potassium sulfate has exhibited a similar variability in this same band, . ~ _-_ Table V. Characteristic Frequencies i n Complex Ions Complex I o n Fe(CN)s--Fe(CKjc---Fe(CS)sNO-- cm.- 1 2100 -2010 2140 1923 847 Ce(S0ds- - 1336 1430 745 SO? 1080 1260 1420 1530 Simple Ion csC?i cs - XO (gac) SOP SO,- cm.-1 2070-80 2070-80 2070-80 1878 820-33 1235-80 1328-80 i26-40 815-35 ... 13.40-80 I t is much safer to base arguments on the identity of spectra than on their nonidentity. >lore empirical experience with the spectra of salts from many different' sources should improve t,his situation. Miscellaneous Observations. AXOMALOUS DISPERSION ANU CHRISTIAXSEN FILTER EFFECTS.These have been adequately described in the literature ( 5 , 9). Examples will be seen in the steep-sided band of magnesium carbonate a t 3 microns (No. 13), of sodium thiocyanate near 5 microns (No. 26), and of potassium ferricyanide near 5 microns ( S o . 155). WATERAXD HYDROXYL BAXDS. The sharpness of the \\-ater bands near 3 and 6 microns in sodium and magnesium perchlorate (Nos. 117, l l S ) , and the high value of their 0-H stretching frequency ( >3500 cm.-I), are striking. Apparently t'here is very little hydrogen bonding in these salts. It, is interesting t o note that animoniuni perchlorate (KO. 116), \vhicah forins no hydrate, has a high K-H stretching frequency. Other compounds with sharp water bands are barium chlorate (KO.115) and 1)ai~iuni chloride (No. 159). I n bicarbonate there is a band a t 2500 to 2600 cni.-', in Iiisulfate at 2300 to 2600 cm.-' (very broad), and in HPOI--, H2P04-, HAs04--, and HP;IsO4-at about 2300 em.-' (very broad). Their is evidence that these are 0-H stretching frequencies of the hydroxyl groups attachrd to the rentral atom. B.%RInf CHLORIDE.Several chlorides of the purely ionic type were examined to observe how the hands due to watcr of hydrat,ion varied. Among these was barium chloride dihydrate ( S o . 159). Surprisingly it has a strong band a t 700 cm.-', which )\-as totally unexpected but was c,onfirnied on a second sample. I t is not attributable to carbonate or bicmhonate, hut may tie due to a torsional motion of the w:itcr molecules in tlic lattice. COMPLEXIoss. The rliaracteristic. frequcncic:; carry over moderately wcll into roinplex ions-for exainple, pot ricyanitie has a band a t 2100 c m - l , and each of the rhree ferrocyanides has one near 2010 cni-'. This is obviously thc stretching frequency of the C S - gi'oupj which in simplr ryanides is 2070 to 2080 c i n - ' Other examples are shon.n in Tnl)le V. CoIiPoazrns WITH So ABSORPTIOS.Sickel hydroxide, fci~ic* oside, cadmium sulfide, and mercuric sulfide have no absorption in the rock salt rcgion aside from watcr mid hydroryl hands. ACLYO&LEl)(;\I EX1 The authors are inciel)ted to two colleagues, D. T. P i t i i i x i i and E. S. Hodge, for carrying out t h r x-ray and emission analyses, respectively. Helen Golob prepared many of the curvrs. The Chemistry Departments of the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Institute of Technolog!- graciou3ly provided many of t,he samples. LITERATURE CITED Colthup, N. E . , ,I. Optical S o c 40 397 (lCJ50'. Glockler, G., Rec. M u d e r n I'hys., 15, 111 (1913). Hersberg. G., "Infrared and Raman Spectra of Polyatomic Molecules." Sew I-ork. D. Van Noatrand Co., 1945. (4) Hihhen, J. H., "The Ranian Effect and Its Chemical -ippIications." S e w York. Reinhold Puhlishinrr Coru.. 1939. ( 5 ) Hunt, J . M.,Wisherd. 11.P., and Ronhani, L. k., .is\r.,C H i c v . , 22, 1478 (1950). Lecomte. J., AM^. Chim. d c t n . 2, 727 (1948). (7) Lecomte, J.. C'ahiers p h y s . . 17, I (1943!, and referelives cited therein. (8) Sewman, It.. and €Idford, R. S.. .I. C'Aem. Phys.. 18, 1 2 i 6 , 1 9 1 (6) (1950'. (9) Price, TT. C.. and Tetlow, K. S . , I b i d . , 16, 1157 (194q). (10) Schaefer, C.. and Xlatossi, F.. "Das ultrarote Spektrum," Herlin, Julius Springer., 18:30; repi.inted by Edwards Bi,os., Inc., Ann Arbor, l f i c h . (11) \Vagner, E. L., and I-Ioi,nig, D. F.,J . Chem. P h y s . . 18, 296, 305 (1950). (12) Wu, Ta-You, "Vibrational Spectra and Structure of Polyatomic Molecules," 2nd ed., .%nn .%I hor, Mich., J. W.ICcIwat ds. 1946. RECEITED for review July 3 , 1931 .ici.epted J u n e 7 , 19z2