The Vinyl Touch

advertisement

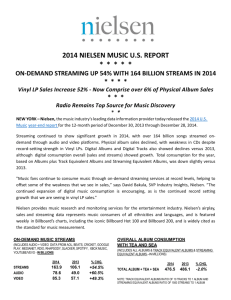

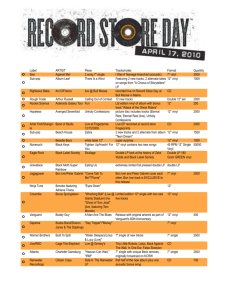

THE VINYL TOUCH Written by OSAYI ENDOLYN Illustration by BARRY LEE “Whoa. Whoa! What album is that?” The Zifty delivery guy pointed behind me. Forty-five minutes earlier, I had ordered a chicken Parmesan sub through Zifty.com. The Zifty people pick up your takeout order from restaurants that don’t deliver, and bring it right to you. I was famished. It was one of those offensively cold nights just before Atlanta was held hostage by snow and ice. My kitchen offered unattractive options ranging from uncooked pasta to granola, and I was not about to brave the weather. So when I opened the door to the nice Zifty man holding my sandwich from Noni’s Italian Deli, I could have grabbed his face and smacked a juicy one right on him. I tipped the man instead. Then things took a detour. 6 S CAN M AGAZ INE » W INTER 2 0 11 W INTER 2 0 11 » SCAN MAGA ZI NE 7 “Do you mind if I take a look at it?” he asked. I was confused at first. This is not how it usually works: I’m hungry, you bring food, I pay you, you leave. Then it clicked. My stairway leading up to the second floor was in clear view, and it was lined with vinyl records. They sit flush against the wall, from top to bottom, kept out of the way by clear plastic bookends. Zifty Man was referencing the front album on the first step. I set down my sandwich and picked up the record, bringing it over to him. music meditation. He stood on one side of the door, I was on the other, an album hovered between us while my chicken Parmesan rested behind me. It smelled delicious. Another minute passed as he commented on Jackson and his love for vinyl in general. Then, a brief silence. If he made a break for it, I wasn’t going to chase him. “Yeah,” he nodded enthusiastically. “I hope you don’t mind. I’m a part-time DJ and I collect records. I love Joe Jackson, but I’ve never seen that album.” It must have looked odd. A moment earlier we were strangers, connected solely by my hunger pains. Suddenly, we were sharing some kind of 8 S CAN M AGAZ INE » W INTER 2 0 11 A DIFFERENT WORLD Some of the records were purchased, most we adopted. There’s a lot of good music out there that faces abandonment. Rod Stewart, Stevie Wonder, Frank Sinatra, Prince — they needed a home, so we took them in. And where does one put 600 albums? Everywhere. They line both stairways in our townhome. They are framed artwork on the walls. They are conversation starters stacked underneath the coffee table. You can’t go anywhere in my house without running into an album. “The Joe Jackson?” The record in question was “Body and Soul,” released in 1984, influenced by jazz, pop and salsa. The cover is striking. The 30-year-old Jackson is posed against a black background and he’s tinted a fiery red. His saxophone is front and center, and he holds a burning cigarette while staring into the distance. The artwork on “Body and Soul” pays homage to the 1957 release “Vol. 2” by Sonny Rollins, master saxophonist of the bebop era. Zifty Man held the record in his hands, turned it over to check out the track listing and then back to the front to stare at the artwork. My door was still wide open. Every bit of that night’s wind chill was whipping through my house. The front of my body facing the door was frozen, and my backside was losing warmth by the second. But I couldn’t rush him. He was totally romanced. stepped through my front door and walked up that stairway, he might have wanted to smack a juicy one on me. My husband and I own about 600 albums. At some point counting them became silly. “Sorry,” he said finally, with an apologetic laugh. He handed the record back to me. “No worries,” I said, “I totally get it.” And I did. Hours later, after I had wolfed down my sandwich, that moment stuck with me for its tenderness and its awkwardness. Music has a way of forcing people to act on their instincts, in spite of themselves. Delivery guys don’t make conversation — they’re in a rush, they’ve got other people’s doors to knock on. Zifty Man deviated from the routine not only because he was a Joe Jackson fan, but because of the impact that seeing a stairway lined with albums has on a music lover. Had Zifty Man Each record has its own richness – not just because of the music it holds, but because of the sensation you get when you hold it. Something fragile bubbles up, something you miss out on with an MP3 file, streaming music, or even a CD. I’m not talking about the audiophile debate that’s gone on since the dawn of digital, or the efficacy of vinyl sound quality versus other mediums. I’m talking about that tactile element. The thing that made Zifty Man linger on my doorstep. Whatever that thing is, a lot of us have experienced it, and it’s contagious. Reports that album sales have increased steadily every year are no longer news. Today, smart musicians release a vinyl record along with a digital version, especially if they’re independent artists. Turntable purchases are going to young people, and their parents are buying iPods. As someone who can’t remember a time when CDs weren’t an option, I find that strange. But it’s happening all over, and no one really knows why. Some say it’s the vinyl sound – like crinkling paper or a fire popping — that accentuates the listening experience. Others say the methodology wins. Everything slows down when you’re jamming to a record; moving a needle to a specific point is not as easy as clicking the arrow in iTunes. Still, others promote the visual candy. Album artwork is ubiquitous today; it’s hard to believe that the concept of putting art on a cover wasn’t invented until 1938 (plain cardboard sufficed until then). The innovative Alex Steinweiss, Columbia Record’s first art director, invoked a new way for artists to promote their music, and for consumers to think about the mood behind their favorite songs. Would Joni Mitchell’s “Blue” sound the same without the deep blue headshot of her close-to-tears face? Sure, it would. But would it feel the same? I’m not so sure. TAKE A RETROSPECTIVE Perhaps to understand what’s happening in today’s record bins, we should examine the way it used to be. Our parents are good resources. If you ask them, they might recall the days when singles were released on 45s and only on Fridays. For that reason, Fridays were special and full of excitement. Discussions at school would ultimately turn toward what was coming out that weekend and what you thought it would sound like. They might remember a time when records sold out, just poof, they were gone, and weeks would go by before a new shipment came. In order to hear the album in question, you had to go to a friend’s house, because they ditched class and waited in line to buy it. Everyone would gather around and listen or dance, sometimes both, but you couldn’t go too far away — in less than 30 minutes you had to turn the record over. If you played an instrument, your popularity increased by how quickly you could learn the new songs and perform them with your fellow band mem- bers. The very acquisition of music made it a collective experience, something you had to share with others. That’s just how it was. And even when you were alone and it was just you and your album, you could hold the liner notes and cover in your hands. You could stare at the lyrics and read the acknowledgments over and over, until you looked at them without seeing. And sometimes, the record would sound so perfect, the music would stop, but that hissing noise that records make when they keep spinning would come through the speakers, and you would just sit there and keep thinking about whatever it is you think when something has inspired you, or made you wistful. If you ask your parents, or your aunts and uncles, that’s what they might say. If they leave out the part where the needle was dull and it ruined the record, or how it was hot one day and the vinyl melted in the car, or how when they tried to move, the box broke under the weight of too many albums smashed together — please, forgive them. We’ve convinced ourselves that vinyl takes us “back” somewhere and that it’s a more “authentic” listening experience. It’s not. It just feels good. SOMETHING MORE, SOMETHING GOOD This is typically the part where the author bemoans “The State of Music Today” and how the latest advances in technology have wreaked havoc on our society. You won’t hear me complain about any of that. I love living in a time where all 6,524 songs in my iTunes can fit in the palm of my hand. I like that I can buy one song if I only like that one, and the other 12 can stay wherever songs live in Apple world when you don’t buy them. I don’t mind that clicking “Buy” is a solitary experience and that I don’t lose my breath from anticipating a new release because it streamed on NPR for free. And I love hitting “Play,” then “Shuffle,” and walking away from my computer, knowing that days could pass before all the songs play. But I wonder sometimes if we’re missing something special. I wonder if some hidden gene lodged in that place only music goes, is leading us back to — there, I said it — a time when you didn’t just share music with friends, you experienced it together. I guess that’s what Ping and Pandora try to cultivate by showing what your friends are listening to, and recommending new artists based on your tastes. They’re certainly effective; millions of satisfied users indicate as much. But they don’t give you that warm and fuzzy feeling. There’s also artistic integrity to consider. Some musicians’ projects are based on a concept and the music is meant to be listened to in order, start to finish. Take Neko Case’s “Middle Cyclone” or Janelle Monáe’s “The ArchAndroid.” The album as a medium certainly favors their visions. Don’t we get something out of hearing a piece of music the way it was intended? And haven’t we proven we’re unreliable when given the (digital) reins? Admit it, sometimes we need guidance. Not because our views of music are pedestrian, but because just like a wellcrafted book, some musicians arrange their tracks like chapters. Reading cover to cover is part of the deal. Maybe this is the new happy medium: a little digital for your everyday, a little vinyl for your soul. That’s the only way I know to explain the sense of security I feel when a record is playing. That’s all I can say when visitors wonder why we have so many records. And it’s the only way I can understand the stillness and admiration that came over Zifty Man so quickly, and to justify that I was close to inviting him in. Just to talk. About music. Because even when you’re hungry and cold and not thinking about music, when you connect with someone over an album that you forgot you had, the dynamics change. You soften. And you listen. As I placed the record back on the step, Zifty Man apologized again. “You just don’t come across too many people,” he started to say. “I know,” I said, “I know.” » W INTER 2 0 11 » SCAN MAGA ZI NE 9