La Traviata - The Metropolitan Opera Guild

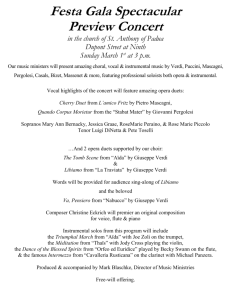

advertisement

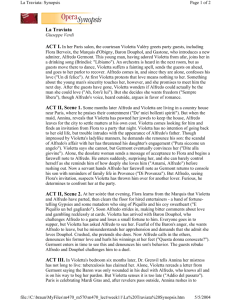

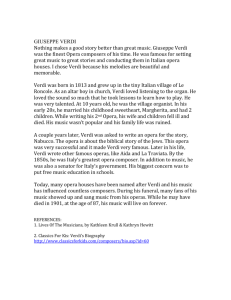

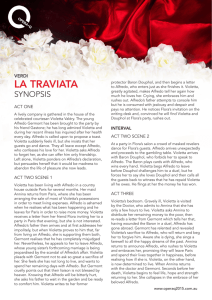

1 Table of Contents An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials 3 Production Information/Meet the Characters 4 The Story of La Traviata Synopsis Guiding Questions 5 7 The History of Verdi’s La Traviata 9 Guided Listening Prelude Brindisi: Libiamo, ne’ lieti calici “È strano! è strano!... Ah! fors’ è lui...” and “Follie!... Sempre libera” “Lunge da lei...” and “De’ miei bollenti spiriti” Pura siccome un angelo Alfredo! Voi!...Or tutti a me...Ogni suo aver Teneste la promessa...” E tardi... Addio del passato... 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 La Traviata Resources About the Composer Online Resources 26 29 Additional Resources Reflections after the Opera The Emergence of Opera A Guide to Voice Parts and Families of the Orchestra Glossary 30 31 35 36 References Works Consulted 40 2 An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials The goal of Pathways for Understanding materials is to provide multiple “pathways” for learning about a specific opera as well as the operatic art form, and to allow teachers to create lessons that work best for their particular teaching style, subject area, and class of students. Meet the Characters / The Story/ Resources Fostering familiarity with specific operas as well as the operatic art form, these sections describe characters and story, and provide historical context. Guiding questions are included to suggest connections to other subject areas, encourage higher-order thinking, and promote a broader understanding of the opera and its potential significance to other areas of learning. Guided Listening The Guided Listening section highlights key musical moments from the opera and provides areas of focus for listening to each musical excerpt. Main topics and questions are introduced, giving teachers of all musical backgrounds (or none at all) the means to discuss the music of the opera with their students. A complimentary CD of the full opera, as well as the full libretto (with English translation), are provided as part of the Guided Listening resources and are sent via mail. Guiding Questions / Discussion Points Guiding Questions or Discussion Points appear within several sections of these materials to spark discussion in your classroom and facilitate student exploration. Note that these questions are not intended to serve as “official” learning outcomes for the opera experience; rather, we hope that they act as a point of departure for prompting meaningful analysis and conversation amongst students. We are aware that teachers incorporate the study of opera into their classrooms in many ways and to address a variety of student outcomes, and we expect that individual teachers will adapt these materials to best serve their specific curriculum and instructional goals. CD Provided Verdi: La Traviata Libretto Provided (with CD) Verdi: La Traviata Sutherland, Pavarotti, Manuguerra National Philharmonic Orchestra Richard Bonynge (Conductor) Sutherland, Pavarotti, Manuguerra National Philharmonic Orchestra Richard Bonynge (Conductor) Copyright 1991 The Decca Record Company Limited Copyright 1991 The Decca Record Company Limited 3 Production Information Music: Giuseppe Verdi Text (Italian): Francesco Maria Piave, after the novel La Dame aux Camélias, by Alexander Dumas fils World Premiere: Venice, Teatro La Fenice March 6, 1853 Meet the Characters Violetta Valéry (soprano): A courtesan suffering from consumption (tuberculosis). Flora (mezzo-soprano): Violetta’s friend. The Marquis d’Obigny (bass): Flora’s protector. Baron Douphol (baritone): An admirer of Violetta’s. Dr. Grenvil (bass): Violetta’s doctor. Alfredo Germont (tenor): Violetta’s lover. Annina (soprano): Violetta’s maid. Giorgio Germont (baritone): Alfredo’s father. 4 The Story of La Traviata: Synopsis Act I Violetta Valéry knows that she will die soon, exhausted by her restless life as a courtesan. At a party she is introduced to Alfredo Germont, who has been fascinated by her for a long time. Rumor has it that he has been enquiring after her health every day. The guests are amused by this seemingly naïve and emotional attitude, and they ask Alfredo to propose a toast. He celebrates true love, and Violetta responds in praise of free love. She is touched by his candid manner and honesty. Suddenly she feels faint, and the guests withdraw. Only Alfredo remains behind and declares his love. There is no place for such feelings in her life, Violetta replies. But she gives him a camellia, asking him to return when the flower has faded. He realizes this means he will see her again the following day. Alone, Violetta is torn by conflicting emotions—she doesn’t want to give up her way of life, but at the same time she feels that Alfredo has awakened her desire to be truly loved. Act II Violetta has chosen a life with Alfredo, and they enjoy their love in the country, far from society. When Alfredo discovers that this is only possible because Violetta has been selling her property, he immediately leaves for Paris to procure money. Violetta has received an invitation to a masked ball, but she no longer cares for such distractions. In Alfredo’s absence, his father, Giorgio Germont, pays her a visit. He demands that she separate from his son, as their relationship threatens his daughter’s impending marriage. But over the course of their conversation, Germont comes to realize that Violetta is not after his son’s money—she is a woman who loves unselfishly. He appeals to Violetta’s generosity of spirit and explains that, from a bourgeois point of view, her liaison with Alfredo has no future. Violetta’s resistance dwindles and she finally agrees to leave Alfredo forever. Only after her death shall he learn the truth about why she returned to her old life. She accepts the invitation to the ball and writes a goodbye letter to her lover. Alfredo returns, and while he is reading the letter, his father appears to console him. But all the memories of home and a happy family can’t prevent the furious and jealous Alfredo from seeking revenge for Violetta’s apparent 5 betrayal. At the masked ball, news has spread of Violetta and Alfredo’s separation. There are grotesque dance entertainments, ridiculing the duped lover. Meanwhile, Violetta and her new lover, Baron Douphol, have arrived. Alfredo and the baron battle at the gaming table and Alfredo wins a fortune: lucky at cards, unlucky in love. When everybody has withdrawn, Alfredo confronts Violetta, who claims to be truly in love with the Baron. In his rage Alfredo calls the guests as witnesses and declares that he doesn’t owe Violetta anything. He throws his winnings at her. Giorgio Germont, who has witnessed the scene, rebukes his son for his behavior. The baron challenges his rival to a duel. Act III Violetta is dying. Her last remaining friend, Doctor Grenvil, knows that she has only a few more hours to live. Alfredo’s father has written to Violetta, informing her that his son was not injured in the duel. Full of remorse, he has told him about Violetta’s sacrifice. Alfredo wants to rejoin her as soon as possible. Violetta is afraid that he might be too late. The sound of rampant celebrations are heard from outside while Violetta is in mortal agony. But Alfredo does arrive and the reunion fills Violetta with a final euphoria. Her energy and exuberant joy of life return. All sorrow and suffering seems to have left her—a final illusion, before death claims her. THE METROPOLITAN OPERA 6 The Story of La Traviata: Guiding Questions Act I: One Happy Day • Why are the guests all so amused by Alfredo? What kind of a social scene is presented at this party? What sort of society does Violetta reside in? • Why is it so hard for Violetta to believe in the kind of sentiment that Alfredo expresses so easily? What does her skepticism say about the sort of life she has lived? • Think about the character of Violetta. Do you think she is truly independent? Do you think she is happy in her life? Why or why not? Act II: Father Knows Best • How could Alfredo be unaware that Violetta was paying for their life together by selling her things? What does his lack of awareness show about his disposition? • Do you think Giorgio Germont’s desire to end his son’s romance is truly in order to protect Alfredo? Do you perhaps think he might have a more selfish motive for wanting to be rid of Violetta? • Why does Violetta lie to Alfredo about being in love with Baron Douphol? How does Alfredo react? Act III: A Bittersweet End • Think of the relationship between Doctor Grenvil and Violetta. How is it that such an epicenter of society like Violetta would in the end really only have one loyal friend, Doctor Grenvil. What does this say about her world and Violetta’s place within it? • Why do you think Alfredo’s father has a change of heart about his son and Violetta? Do you think he just feels guilty because Violetta is dying or is it something more? 7 Act III: A Bittersweet End (continued) • Why might Violetta abruptly feel better, only to die suddenly? What does this say about her mental state? Or is her sickness preempted by Alfredo’s reappearance? Do you think Violetta dies peacefully? 8 The History of Verdi’s La Traviata La Traviata was conceived in 1852, the year that Alexander Dumas’ play La Dame aux Camélias went onstage at the Vaudeville in Paris. In July, composer Giuseppe Verdi had not yet settled upon the subject and libretto of the new opera he was to write for the Teatro la Fenice in Venice. In a letter to Marzari, president of that theater, Verdi wrote, “If there were a first-rank prima donna in Venice, then I would have ready a sure-fire subject, one that could not fail; but things being what they are, we must look for something suitable and adaptable to the situation.” This sure-fire subject—“simple and filled with love”, as Verdi described it on another occasion—was the story of Dumas’ heroine Marguerite Gautier. Verdi composed it to Francesco Maria Piave’s libretto in Busseto and Rome during the fall and winter of 1852–1853. While he was working on the score, he received bad news from Paris regarding Fanny Salvini-Donatelli, the soprano who La Fenice had engaged to sing Violetta. From Cremona on January 20, 1853, he wrote to La Fenice asking the management to engage someone else, a “real prima donna”—such as Rosina Penco, who had sung Leonora in the successful world premiere of Il Trovatore in Rome ten days earlier. But La Fenice dragged its feet. It was February, and La Traviata was scheduled to go onstage in less than a month. The composer left for Venice prepared for the worst. Rehearsals began during the last week in February, immediately after his arrival. Lodged at the Hotel Europa on the Grand Canal, Verdi worried about the singers: they misunderstood the music and the play, they ignored his instructions, and they showed little interest in the work. The first performance took place on March 6, 1853. On the March 7th and 9th Verdi wrote as follows: To his secretary-pupil Emanuele Muzio: “La Traviata last night, fiasco. Is it my fault or the fault of the singers? Time will tell.” To Ricordi, his publisher: “I am sorry to give you the sad news, but I cannot hide 9 the truth. La Traviata was a fiasco. Let us look for the causes. This is the story. Addio, addio.” To Luccardi, the sculptor, in Rome: “It was a fiasco! A solid fiasco! I don’t know whose fault it was: it is better not to talk about it. I won’t say anything about the music; and allow me to say nothing about the singers. Give this news to Jacovacci [the impresario of the Teatro Apollo in Rome] and say this is my answer to his last letter, in which he asks me about one of the cast.” For more than a century Verdi’s reports had been accepted at face value. However, other sources paint a different picture of Traviata’s first performance. Immediately after the prelude to the first act, the public began to shout for Verdi, who had to take curtain calls even before the curtain went up. He was called out again after the Brandies, after the Alfredo-Violetta duet “and I don’t know how many other times— alone and with the prima donna at the end of the first act.” So wrote Tommaso Locatelli, a well-known Venetian critic, the reviewer for the newspaper La Gazzetta Uffiziale di Venezia. As for Salvini, over whom Verdi had been apprehensive, “she ravished the public, which deluged her with applause.” The review continues, “The music was magnificently played by the orchestra, so much so that the delicious prelude of the third act got and deserved a unanimous round of shouted cheers…The public was ravished by the most beautiful and lively melodies that have been heard in a long time…Anyone who does not see the beauty of ‘Un dì, quando le veneri’; anyone who does not feel moved by those ‘Piangi’, neither played nor sung but spoken by the orchestra; anyone who does not feel his heart tremble with that musical sigh of ‘Pietà, gran Dio, di me’; anyone who is not moved by those moments has no right to talk about music.” On the debit side the reviewer notes that “three things are needed for the art of music: voice, voice, and voice. And truthfully, Verdi has created something beautiful, even though he does not have an artist who understands and can perform what he creates. Last night Verdi had the bad luck to lack those three things mentioned above, and all the pieces not sung by Mme. Salvini-Donatelli went by the line, so to speak.” 10 Certain pieces for the tenor and baritone fell below par: “Di Provenza il mar” was sung in its original uncut form and was thus too long. The tenor was in bad voice for the difficult aria he must deliver at the beginning of Act II. But apart from these moments, which laid a certain chill on the audience, the performance went reasonably well. La Traviata was repeated ten times during its first season at La Fenice—only four performances fewer than Rigoletto had in 1851, and remains one of the most treasured of Verdi’s operatic hits. 11 Guided Listening: Prelude CD 1, Track 1 | Libretto pg. 36 A prelude opens the first act of La Traviata. Discussion Points • Define “prelude.” What is the purpose of a “prelude” from a composer’s perspective? • What is the tone, or mood, of the prelude at the very beginning, until1:32? Is the tone morose, exuberant, romantic, silly, melancholy, or something else? o What is the section of the orchestra that you hear most predominately during this musical selection? Do you hear multiple sections playing in the orchestra? If so, what sections are playing throughout the excerpt? • What happens at 1:32? What major change do you notice? How does this change affect the mood of the excerpt? o How might you describe this new tone or musical feeling? o What musical changes happen in this moment? Do you hear a change in tempo? Is there a change in tonality? o Does the orchestra section that was playing most strongly in the beginning half of the expert change after 1:32? If so, how does it change? What orchestral sections are added or taken away at this point? continued on next page 12 Discussion Points (continued) • Based on your previous answers, what two tones or moods, are explored in the prelude? o Why might Verdi have written this distinct musical juxtaposition within his prelude? Do you think he was foreshadowing the story and events to come? Explain. 13 Guided Listening: “Brindisi: Libiamo, ne’ lieti calici” CD 1, Track 3 | Libretto pg. 46-56 Alfredo sings about the joy of living in the moment while the woman he has loved in secret for over a year, Violetta, looks on in interest. Alfredo alludes to his feelings for Violetta, while Violetta explains she will never know the life of constant and consuming love. Discussion Points • What is your impression of this piece? How might you describe the tone or feeling of this music? o Would you describe the music as happy, sad, relaxed, or excited? What about the music gives you that feeling? o Is there a musical technique or gesture that is used during this selection that gives you this impression? If so, give specific musical or textual references to explain your reasoning. • What is happening in this scene? What is the setting? Are there many people on stage or just a few? o If you were the set designer for this opera, how would you “set” the scene? What would the set pieces look like? Would they be opulent or sparse? Explain. o If you were the costume designer for this opera, how would you clothe the singers? Would they be in plain or fancy clothing? Explain. • What word would you use to describe the music in this excerpt? Is it lush, evocative, mysterious, dance-like, or something else? o How does the text relate to the music, and vice versa? o What kind of dance does the music remind you of? o Why might the composer—Giuseppe Verdi—have chosen to include this type of music in this scene? continued on next page 14 Discussion Points (continued) • We are introduced to Alfredo in this excerpt. Describe him. o What do you imagine he looks like? What seems to be his role among the party-goers? o What voice part is Alfredo? Does he have a high or low voice part? How would you describe his music? • How does Violetta feel about Alfredo and his speech? Are they in agreement? o Why might she be wary of Alfredo and his declaration of life? Do you think she believes that he is genuine? Do you think she is excited or scared by what she hears? o Support your answer using specific excerpts from the libretto. 15 Guided Listening: “È strano! è strano!... Ah! fors’ è lui...” and “Follie!... Sempre libera” CD 1, Tracks 6-7 | Libretto pp. 62-66 Violetta finds that her feelings for Alfredo are getting stronger. Discussion Points Track 6 • Do you get the sense that Violetta is comfortable with her growing love for Alfredo? Why or why not? o Do you think this was something that Violetta predicted for her life? Do you think she is excited or saddened by the idea of loving Alfredo? o What might be scaring her? Do you think her health is a factor in her view on love? Explain. • Do you hear a change in the music early in the excerpt? Where does that change occur? o What changes do you hear in the melody–—does it become smoother (“legato”) or more disjointed (“staccato”), or something else? o What changes do you hear in the instrumental texture, if any? Are there more instruments (fuller texture), or fewer instruments (sparser texture)? o What changes do you hear in the dynamics—is the music louder (“forte”) or softer (“piano”)? o What tempo changes do you hear? Does the music become faster or slower? o What does this change, or break, indicate in the music structure? Does it indicate the start of the main section of the excerpt—the aria? How can you tell? Use the libretto, as well as your answers to the previous questions to help you decide. continued on next page 16 Discussion Points (continued) Track 7 • What happens at the beginning of the second track? What happens to the mood, or tone, of the excerpt, based on both the music and the libretto? o What about the music changes? Do you hear a shift in tempo? Is there a change in the tessitura, or range, in which Violetta sings? o Does Violetta’s music become more or less embellished in this track? What might this imply about her emotional state in this moment? • How do Violetta’s feelings change by the end of the excerpt? Has she become more or less confident in the love between her and Alfredo? o Do you imagine she will be able to forget Alfredo and go back to her normal lifestyle? Explain. • Does Violetta seem to be experiencing an internal conflict? If so, about what is she conflicted, and why? Think about who she is in this moment, and think about possible instances in her past that might be holding her back from accepting her feelings for Alfredo. o What would you do if you were in Violetta’s situation? 17 Guided Listening: “Lunge da lei...” and “De’ miei bollenti spiriti” CD 1, Track 8-9 | Libretto pg. 66-67 Alfredo explains his understanding of what Violetta has given up in order to be with him. Here he exclaims his joy and thankfulness for the love and sacrifice she has given him. Discussion Points Track 8 • This excerpt begins Act II. Where are Alfredo and Violetta? How long have they been there, and why did they leave Paris? o Why is Alfredo in hunting clothes? Where is Violetta? Use specific references from the libretto and music to support your answer. • What is the mood, or tone, of this excerpt? Is it lethargic, exuberant, jolly, downhearted, or something else? o How does the mood connect with the libretto, and the words Alfredo sings? o Do you think that Alfredo is happy? How are you able to tell? What elements in his music inform you of his feelings? Use examples to explain your reasoning. • Alfredo sings of what Violetta has sacrificed for their relationship. o In the last excerpt we heard, Violetta was experiencing conflicting feelings about her relationship with Alfredo. What might have changed her mind? If you aren’t sure, make an educated guess based on what you know about the story. o What does Alfredo say that Violetta has sacrificed? What choice would you have made in Violetta’s position? continued on next page 18 Discussion Points (continued) Track 9 • Do you believe that Alfredo is correct in saying that he has “forgotten the world and lived like one in heaven…?” o Do you think that Alfredo has given up as much as Violetta to be together? o Do you think the happiness between Violetta and Alfredo is forever? Why or why not? o How might Violetta feel about the situation? • Why do you think that Violetta has not told Alfredo that she is selling all of her possessions so that they can live together in the country? o Do you think that Violetta is happy to sell her possessions? Why is Alfredo unable to help pay for their new lifestyle? • What do you think will happen to these two lovers? Do you imagine that they will be together forever? Will they move back to Paris and continue their past lifestyles? Explain how you’ve predicted Violetta and Alfredo’s future. 19 Guided Listening: “Pura siccome un angelo” CD 1, Tracks 11| Libretto pg. 78-86 Alfredo’s father, Giorgio Germont, visits Violetta to talk to her about her relationship with his son and to discuss a sacrifice she must make for his family. Discussion Points • What has Giorgio asked of Violetta, and why? Is it fair of him to ask this? Why or why not? Again, think about the conventional roles of men and women during this time. Might Giorgio have no other choice? Explain. • What emotions is Violetta feeling? How do her feelings come across through the music? Which musical element—such as the dynamics (loud/soft), tempo (fast/slow), texture (full/sparse), etc.—is most successful in communicating her emotions? • Are the vocal phrases that Violetta and Giorgio sing in this excerpt similar or different? Why might Verdi have chosen to write such drastically different parts for the two characters in this excerpt? Think about the emotions each is experiencing, and what they both want out of their conversation. • How does Violetta’s reaction to Giorgio’s request change throughout the scene? o Indicate the point in the music and in the libretto where she begins to give in to Giorgio’s wishes. o What does it say about Violetta’s character that she agrees to give up her relationship with Alfredo on his sister’s behalf? o What would you do in Violetta’s position? continued on next page 20 Discussion Points (continued) • Is Giorgio Germont a “likeable character”? Why or why not? Do you think he understands the weight of his request? Support your answer with specific examples from the libretto. 21 Guided Listening: “Alfredo! Voi!...Or tutti a me...Ogni suo aver” CD 2, Track 2 | Libretto pp. 116-135 Violetta sees Alfredo for the first time after leaving him. Discussion Points • Where does this excerpt take place? What has happened since Violetta and Alfredo last saw each other? o Why is Alfredo at the party? Is he there to have a good time or does he have an alternative plan? o Does it seem that Alfredo has any idea about the sacrifice that Violetta made for his family? How are you able to tell? • What does Violetta warn Alfredo about? What is she afraid will happen to him? o What might happen between the Baron and Alfredo? How might the Baron take his revenge out on Alfredo? • How would you describe Alfredo’s words in this excerpt? Are they soothing, stinging, sarcastic, or something else? o How would you feel if you were in Violetta’s position? Why does Alfredo believe so easily that she doesn’t love him? o Do you think that Alfredo still loves Violetta, or do you think that he never really did? Do you think he’s treating her like someone he loves? Why or why not? • This excerpt is a “duet” between Violetta and Alfredo. Compare this duet with others we’ve heard between Violetta and Alfredo throughout the opera. Think about the orchestral accompaniment, as well as the libretto. Are the phrases more narrative or more poetic? Why might the librettist have made this choice? continued on next page 22 Discussion Points (continued) • Do you believe Violetta is being truthful when she says that she loves the Baron and not Alfredo? o Why would she tell Alfredo this? o Does she give Alfredo any indication that she has been forced into this situation? If so where? o What would you do if you were in Violetta’s position? 23 Guided Listening: “Teneste la promessa...” E tardi... Addio del passato...” CD 2, Track 5 | Libretto pg. 146-148 Violetta reflects on life and love. Discussion Points • What is happening to Violetta? How has she changed? • Listen closely to the orchestral accompaniment. o Is the orchestral accompaniment full or sparse? o Is the accompaniment mostly “legato” (smooth) or “staccato” (detached), or a mix? o How do these musical elements help to communicate Violetta’s feelings in this excerpt? Do they seem to match the words she is singing? Explain. • What happens around 1:55? o Does the musical phrase Violetta sings “ascend” (get higher) or “descend” (get lower)? o On what word does the phrase reach its highest point? What is the significance of this word? o Would you characterize Violetta as a spiritual individual, based on what you know about her character? Is her seeking solace in God surprising? Why or why not? • Does Violetta regret her past and the choices she has made? Reference the libretto to support your answer. continued on next page 24 Discussion Points (continued) • Do you hear any repeated musical material in the aria? If so, where? o Why might Violetta be repeating herself in this moment? Is she alone or with people? • This is not the end of the opera. What do you think will happen next? Will Alfredo and Violetta be reunited once again? 25 La Traviata Resources: About the Composer Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) The son of innkeepers in Roncole, Italy, Giuseppe Verdi is thought to have been born sometime between October 9th and October 11th, 1813 (the records of the exact date are unclear). Although Verdi did not come from a family of notable wealth, his parents were able to afford to arrange for their son to apprentice to the town’s organist, with whom he showed enough aptitude to pursue studies in the nearby town of Busseto. Confident in his musical potential, and with the financial assistance of a fatherly benefactor (a greengrocer by the name of Antonio Barezzi), Verdi traveled to the Milan Conservatory for further study at the age of nineteen. Upon arrival in Milan, Verdi was considered to have neither the youth nor the proficiency at the keyboard to succeed at the conservatory, and he was refused enrollment. Despite this rejection, Verdi studied privately with an accompanist at La Scala1, who encouraged him regularly to attend the opera. As his musical career began to take shape, Verdi married Margherita Barezzi, the daughter of his financial benefactor, at the age of twenty-three. Only three years later, he completed his first opera—Oberto—which promptly premiered at La Scala in 1839. Following the success of his first opera, Verdi encountered a series of tragedies that nearly caused him to abandon music. In April 1840, Verdi’s young son fell ill and died, followed by his daughter only two days later. In June, his wife Margherita had an attack of acute encephalitis and also died. Verdi’s life was shattered; he left Milan and returned to the town of Busseto in grief. It wasn’t until two years later, when he discovered the libretto Nabucco (a tale of the plight of the biblical Hebrews), that his interest in opera was revived. Nabucco became a great success, and its portrayal of oppression was understood as a political statement in Italy, where citizens often felt oppressed by the reigning Austrian Empire. 1 La Scala (or, Teatro alla Scala) is one of the world’s most famous opera houses, and has premiered famous works by composers such as Giacomo Puccini, Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and of course, Giuseppi Verdi. 26 Verdi’s name became synonymous with the political movement to free and unify Italy, and his public stature continued to grow. With the success of Nabucco still ringing throughout Italy, the reinvigorated Verdi went on to compose some of the most important (and successful) operas in all of opera history, including Rigoletto, La Traviata, Il Trovatore, and Aida. But Verdi did not complete such masterpieces alone, and as early as 1843 (one year after Nabucco), he began correspondence with the poet Francesco Maria Piave, who would eventually write ten librettos for him between 1843 and 1862. Verdi played a major role during the Risorgimento (Reunification), the movement to free Italy from foreign rule and to unify the Italian Peninsula into a single nation. In 1848, while Verdi was working at the Paris Opera House, revolts broke out across Europe. Verdi promptly returned to Italy upon hearing the revolution had broken out in Milan, a city ruled by the Austrian government. Throughout this time, Verdi supported the Risorgimento through various deeds and compositions. Eventually, the movement paid off and Italy gained its unification. Verdi was recognized as a leader of the Risorgimento and became a member of the first national parliament in 1861. In addition to his political exploits in Italy, Verdi was fascinated by the political landscape of Spain. Four of his operas, Ernani (1844), Il Trovatore (1853), La Forza del Destino (1863), and Don Carlo (1867) are set in Spain or written on Spanish themes and stories. These operas reveal opinions Verdi and his contemporaries held about Spain, a country where race, passion and politics were intertwined. Verdi’s treatment of each of these themes was innovative during his day. We see Moors and Gypsies mistreated by fiery Spaniards, and shadows of the Inquisition. Of the three “Spanish” operas, only Don Carlo was written after the composer’s trip to Spain. Though his career was by no means finished, Verdi retired at the age of 58 to his estate, Sant’Agata, with his second wife, the well-known soprano Giuseppina 27 Strepponi. Over the next several years he wrote his famous Requiem Mass, as well as a string quartet. In 1887, at the surprising age of 74, Verdi shook the opera world with his masterpiece Otello, based on William Shakespeare’s Othello. Six years later the 80-year-old composer produced another masterpiece, yet again from Shakespeare. The opera was Falstaff, based on the play The Merry Wives of Windsor. In the winter of 1901, after the loss of his wife Giuseppina and many of his friends, Verdi suffered a stroke in his hotel suite in Milan. After the simple funeral he requested, he was given a public funeral of the size and scope usually reserved for chiefs of state. He was 88 years old. 28 La Traviata Resources: Online Resources Note: click on the blue link below the description to visit the corresponding page. Video Clips • La Traviata 2013-14 – Highlights Production Preview, San Francisco Opera (2014) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBV8mHu5u4g • Verdi's La Traviata at Lyric Opera of Chicago Production Preview, Lyric Opera of Chicago https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qo6XReu4c5w • Ailyn Pérez on La traviata – Interview Artist Interview, Royal Opera House (2011) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5S8ZDYwHTEo • La Traviata: In the Director’s Chair with John Hoomes Informational Interview, Nashville Opera (2011) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5tVNCkCJxQs • Sempre Libera from La Traviata: Sung by Emma Matthews Opera Excerpt, Opera Australia (2011) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vu901LTyypM • La Traviata – Metropolitan Opera – Poplavskaya and Polenzani Opera Excerpt, The Metropolitan Opera (2010) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u9JyY8v4iLQ • VERDI, G.: Traviata (La) (Arthaus Musik; Naxos) Recording Excerpts, NTSC (Uploaded 2010) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1NRJGq1aD68 • Giuseppe Verdi’s La Traviata Opera Excerpts, Los Angeles Opera (2009) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4PPYYTGzZfE Articles and Other Links • “In Focus: La Traviata” from The Metropolitan Opera http://www.metoperafamily.org/metopera/news/features/infocus-traviata.aspx • “That Was Then: Zeffirelli on La Traviata” by Caroline Cooper for WQXR (January 14, 2011) A 1983 Interview on WQXR Reveals Director's Thoughts on Verdi Opera. http://www.wqxr.org/#!/articles/wqxr-features/2011/jan/14/that-was-then-zeffirelli-la-traviata/ • “Romance and Remorse: Verdi’s La Traviata” from NPR Music’s World of Opera (June 27, 2008) If you spend much time reading about opera, you’ve probably seen comparisons between operas and movies…in 19th-century Europe, operas were a popular form of large-scale, massmarket entertainment. http://www.npr.org/2008/06/27/91958409/romance-and-remorse-verdis-la-traviata 29 Additional Resources: Reflections after the Opera After every opera performance, the director, conductor, and performers reflect and evaluate the different aspects of their production, so that they can improve it for the next night. In a similar way, these Guiding Questions encourage active reflection, both individually and collectively, on your student’s opera experience. Think about the portrayal of the characters in the production at the Met. • How were the characters similar or different from what you expected? Try to identify specific qualities or actions that had an impact on your ideas and thinking. • Did the performers’ voices match the character they were playing? Why or why not? • Did any characters gain prominence in live performance? If so, how was this achieved? (Consider the impact of specific staging.) • What did the performers do to depict the nature of the relationships between characters? In other words, how did you know from the characters’ actions (not just their words) how they felt about the other characters in the story? • Stereotypically, most opera performers are considered singers first, and actors second. Was this the case? How did each performer’s portrayal affect your understanding of (or connection with) their character? Consider the production elements of the performance. • How did the director choose to portray the story visually? Did the production have a consistent tone? How did the tone and style of each performer’s actions (movement, characterization, staging) compare with the tone and style of the visual elements (set design, costume design, lighting design)? • How did the set designer’s work affect the production? Did the style of the setting help you understand the characters in a new way? • How did different costume elements impact the portrayal of each character? • How did the lighting designer’s work affect the production? • Did you agree with the artistic choices made by the directors and designers? If you think changes should be made, explain specifically what you’d change and why. 30 Additional Resources: The Emergence of Opera The origins of opera stretch back to ancient Greece, where playwrights used music and dance to augment moments of action in their stories. At this time, it was popular to write plays in Attic, a sing-song language, where half the words were sung and half were spoken. Dance was also a pivotal part of Greek drama; a chorus danced throughout scenes in an effort to highlight the play’s themes. The philosopher Aristotle, in ‘The Poetics,’ outlined the first guidelines for drama, known as the Six Elements of Drama. Aristotle suggested that a play’s action should take place in one day, portray only one chain of events, and be set in one general location. Over the centuries, playwrights and composers took Aristotle’s advice more seriously. The tradition of including music and dance as an integral part of theatre continued through Roman times and into the Middle Ages. Liturgical drama, as well as vernacular plays, often combined incidental music with acting. Opera can also be traced to the Gregorian chants of the early Christian Church. Music was an integral part of worship, and incorporated ancient melodies from Hebrew, Greek, Roman, and Byzantine cultures. The Church’s organization of music throughout the early Middle Ages gave it structure, codifying scales, modes, and notation to indicate pitch and rhythm. The chants were originally sung in single-line melodies (monophony), but over time more voices were added to compliment the main melody, resulting in the beginning of polyphony (many independent voices or parts sung simultaneously). However, the Church objected polyphony, worried that the intricate weaving of melodies and words obscured the liturgical text. Since conveying the meaning of the text was the primary reason for singing in church, polyphony was viewed as too secular by Church leaders, and was banished from the Liturgy by Pope John XXII in 1322. Harmonic music followed, which developed as songs with one-line melodies, accompanied by instruments. Then, in 1364, during the pontificate of Pope Urban V, a composer and priest named Guillaume de Machaut composed a polyphonic setting of 31 the mass entitled La Messe de Notre Dame. This was the first time that the Church officially sanctioned polyphony in sacred music. Another early contributor to the emergence of opera was Alfonso the Wise, ruler of Castile, Spain, in the 13th century. Also known as the Emperor of Culture, he was a great troubadour and made noted contributions to music’s development. First, he dedicated his musical poems, the “Cantigas de Santa Maria,” to Saint Mary, which helped end the church’s objection to the musical style. His “Cantigas” are one of the largest collections of monophonic songs from the Middle Ages. Secondly, he played a crucial role in the introduction of instruments from the Moorish kingdoms in southern Spain. These instruments, from the timpani to lute, came from Persia and the Arabic culture of the Middle East. Throughout the European Renaissance (14th – 16th centuries), minstrels and troubadours continued to compose harmonic folk songs which informed and entertained. Some songs were mere gossip; others were songs of love and heroes. These contained a one-line melody accompanied by guitars, lutes, or pipes. Martin Luther (1483 – 1546) continued to reform church music by composing music in his native tongue (German) for use in services. He also simplified the style so that average people in the congregation could sing it. Luther turned to the one-line melodies and folk tunes of the troubadours and minstrels and adapted them to religious texts. His reforms had great impact upon the music of Europe: the common people began to read and sing music. From the church at this time also emerged the motet, a vocal composition in polyphonic style, with Biblical or similar text which was intended for use in religious services. Several voices sang sacred text accompanied by instruments, and this format laid the groundwork for the madrigal – one of the last steps in preparing the way for opera. Sung in the native language of the people in their homes, taverns, and village squares, madrigals were written for a small number of voices, between two and eight, and used secular (rather than biblical or liturgical) texts. 32 When refugee scholars from the fall of Constantinople (1453) flooded Italy and Europe, their knowledge of the classics of Rome and Greece added to the development of European musical traditions. Into this world of renewed interest in learning and culture came a group of men from Florence who formed a club, the Camerata, for the advancement of music and Greek theater. Their goal was to recreate Greek drama as they imagined it must have been presented. The Camerata struggled to solve problems that confronted composers, and were interested in investigating the theory and philosophy of music. The Camerata also experimented with the solo song, a forerunner of the opera aria. Not surprisingly, Greek and Roman mythology and tragedies provided the subject matter of the first librettists. The presence of immortals and heroes made singing seem natural to the characters. Composers used instrumental accompaniment to help establish harmony, which freed them to experiment with instrumental music for preludes or overtures. Development of the recitative and the instrumental bridge enabled writers to connect the song, dance, and scene of the drama into the spectacle which was to become opera. This connector-recitative later evolved into a form of religious drama known as oratorio, a large concert piece which includes an orchestra, a choir, and soloists. Members of the Camerata – Jacopo Peri, Ottavio Rinnuccini, and Jacopo Corsi – are credited with writing the first opera, Dafne, based on the Greek myth. Their early efforts were crucial in establishing the musical styles of the new genre in the early 17th century. A sizeable orchestra was used and singers were in costume. Dafne became famous across Europe. The Camerata set the scene, and onto the budding operatic stage came Claudio Monteverdi. He is considered the last great composer of madrigals and the first great composer of Italian opera. He was revolutionary in developing the orchestra’s tonecolor and instrumentation. He developed two techniques to heighten dramatic tension: pizzicato – plucking strings instead of bowing them; and tremolo – rapid repetition of a single note. Modern orchestration owes him as much gratitude as does 33 opera. In his operas, such as Orfeo (1607), the music was more than a vehicle for the words; it expressed and interpreted the poetry of the libretto. His orchestral combinations for Orfeo were considered to be the beginning of the golden age of Baroque instrumental music. Monteverdi’s experimentation with instruments and his willingness to break the rules of the past enabled him to breathe life into opera. He was far ahead of his time, freeing instruments to communicate emotion, and his orchestration was valued not only for the sounds instruments created but also for the emotional effects they could convey. In his work, music blended with the poetry of the libretto to create an emotional spectacle. His audiences were moved to an understanding of the possibilities of music’s role in drama. 34 Additional Resources: A Guide to Voice Parts and Families of the Orchestra Voice Parts SOPRANO Sopranos have the highest voices, and usually play the heroines of an opera. This means they often sing many arias, and fall in love and/or die more often than other female voice types. MEZZO-SOPRANO, or MEZZO This is the middle female voice, and has a darker, warmer sound than the soprano. Mezzos often play mothers and villainesses, although sometimes they are cast as seductive heroines. Mezzos also play young men on occasion, aptly called “pants roles” or “trouser roles.” CONTRALTO, or ALTO Contralto, or alto, is the lowest female voice. Contralto is a rare voice type. Altos usually portray older females, witches and old gypsies. COUNTERTENOR Also often known as alto, this is the highest male voice, and another vocal rarity. Countertenors sing in a similar range as a contralto. Countertenor roles are most common in baroque opera, but some contemporary composers also write parts for countertenors. TENOR If there are no countertenors on stage, then the highest male voice in opera is the tenor. Tenors are usually the heroes who “get the girl” or die horribly in the attempt. BARITONE The middle male voice. In comic opera, the baritone is often a schemer, but in tragic opera, he is more likely to play the villain. BASS The lowest male voice. Low voices usually suggest age and wisdom in serious opera, and basses usually play kings, fathers, and grandfathers. In comic opera, basses often portray old characters that are foolish or laughable. Families of the Orchestra STRINGS violins, violas, cellos, double bass WOODWIND piccolos, flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons BRASS trumpets, trombones, French horns, baritones, tubas PERCUSSION bass drums, kettle drums, timpani, xylophones, piano, bells, gongs, cymbals, chimes 35 Additional Resources: Glossary adagio Indication that the music is to be performed at a slow, relaxed pace. A movement for a piece of music with this marking. allegro Indicates a fairly fast tempo. aria A song for solo voice in an opera, with a clear, formal structure. arioso An operatic passage for solo voice, melodic but with no clearly defined form. baritone A man’s voice, with a range between that of bass and tenor. ballad opera A type of opera in which dialogue is interspersed with songs set to popular tunes. bel canto Refers to the style cultivated in the 18th and 19th centuries in Italian opera. This demanded precise intonation, clarity of tone and enunciation, and a virtuoso mastery of the most florid passages. cabaletta The final short, fast section of a type of aria in 19th-century Italian opera. cadenza A passage in which the solo instrument or voice performs without the orchestra, usually of an improvisatory nature. chorus A body of singers who sing and act as a group, either in unison or in harmony; any musical number written for such a group. coloratura An elaborate and highly ornamented part for soprano voice, usually written for the upper notes of the voice. The term is also applied to those singers who specialize in the demanding technique required for such parts. conductor The director of a musical performance for any sizable body of performers. contralto Low-pitched woman’s voice, lower than soprano or mezzo-soprano. crescendo Meaning “growing,” used as a musical direction to indicate that the music is to get gradually louder. diatonic scale Notes proper to a key that does not involve accidentals (sharps or flats) ensemble From the French word for “together,” this term is used when discussing the degree of effective teamwork among a body of performers; in opera, a set piece for a group of soloists. 36 finale The final number of an act, when sung by an ensemble. fortissimo (ff) Very loud. forte (f) Italian for “strong” or “loud.” An indication to perform at a loud volume. harmony A simultaneous sounding of notes that usually serves to support a melody. intermezzo A piece of music played between the acts of an opera. intermission A break between the acts of an opera. The lights go on and the audience is free to move around. legato A direction for smooth performance without detached notes. leitmotif Melodic element first used by Richard Wagner in his operas to musically represent characters, events, ideas, or emotions. libretto The text of an opera. maestro Literally “master”; used as a courtesy title for the conductor, whether a man or woman. melody A succession of musical tones (i.e., notes not sounded at the same time), often prominent and singable. mezzo-soprano Female voice in the middle range, between that of soprano and contralto. octave The interval between the first and eighth notes of the diatonic scale opera buffa An Italian form that uses comedic elements. The French term “opera bouffe” describes a similar type, although it may have an explicitly satirical intent. opera seria Italian for “serious opera.” Used to signify Italian opera of a heroic or dramatic quality during the 18th and early 19th centuries. operetta A light opera, whether full-length or not, often using spoken dialogue. The plots are romantic and improbable, even farcical, and the music tuneful and undemanding. overture A piece of music preceding an opera. pentatonic scale Typical of Japanese, Chinese, and other Far Eastern and folk music, the pentatonic scale divides the octave into five tones and may be played on the piano by striking only the black keys. 37 pianissimo (pp) Very softly. piano (p) Meaning “flat,” or “low”. Softly, or quietly. pitch The location of a musical sound in the tonal scale; the quality that makes “A” different from “D.” prima donna The leading woman singer in an operatic cast or company. prelude A piece of music that precedes another. recitative A style of sung declamation used in opera. It may be either accompanied or unaccompanied except for punctuating chords from the harpsichord. reprise A direct repetition of an earlier section in a piece of music, or the repeat of a song. score The written or printed book containing all the parts of a piece of music. serenade A song by a lover, sung outside the window of his mistress. singspiel A German opera with spoken dialogue. solo A part for unaccompanied instrument or for an instrument or voice with the dominant role in a work. soprano The high female voice; the high, often highest, member of a family of instruments. tempo The pace of a piece of music; how fast or how slow it is played. tenor A high male voice. theme The main idea of a piece of music; analogous to the topic of a written paper, subject to exploration and changes. timbre Quality of a tone, also an alternative term for “tone-color.” tone-color The characteristic quality of tone of an instrument or voice. trill Musical ornament consisting of the rapid alternation between the note and the note above it. trio A sustained musical passage for three voices. verismo A type of “realism” in Italian opera during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in which the plot was on a contemporary, often violent, theme. 38 vocalise A musical composition consisting of the singing of melody with vowel sounds or nonsense syllables rather than text, as for special effect in classical compositions, in polyphonic jazz singing by special groups, or in virtuoso vocal exercises. volume A description of how loud or soft a sound is. 39 References: Works Consulted Additional Resources: The Emergence of Opera Albright, Daniel. Modernism and Music: An Anthology of Sources. University of Chicago Press, 2004. Bent, Margaret. The Grammar of Early Music: Preconditions for Analysis, Tonal Structures of Early Music. New York: Garland Publishing, 1999. "Polyphony - New World Encyclopedia." Info:Main Page - New World Encyclopedia. New World Encyclopedia, 2 Apr. 2008. Web. 27 Jan. 2011. <http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Polyphony>. Sadie, Stanley. "Monteverdi, Claudio." The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. New York: Grove's Dictionaries of Music, 1992. 445-53. Sadie, Stanley. "The Origins of Opera." The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. New York: Grove's Dictionaries of Music, 1992. 671-82. Sadie, Stanley. "Peri, Jacopo." The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. New York: Grove's Dictionaries of Music, 1992. 956-58. van der Werf, Hendrick. Early Western polyphony, Companion to Medieval & Renaissance Music. Oxford University Press, 1997. 40