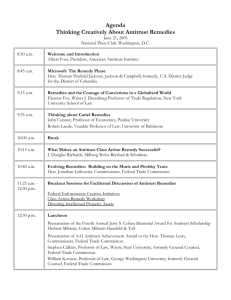

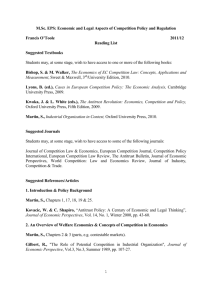

in PDF format - Krannert

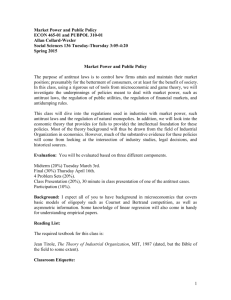

advertisement