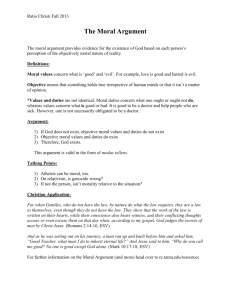

The Moral Argument: a Brief Summary

advertisement

Ratio Christi at Texas A&M The Moral Argument: a Brief Summary Introduction The moral argument is one of a family of arguments attempt to show that the existence of God is plausible given some basic beliefs.1 This argument shows that the objectivity of moral values and duties, if exist, are best explain by a divine being which has the nature of being necessarily good. Different versions of the argument has been given, some are plausible and some are not. However, here I am going to defend what I think the most plausible version of the argument. 1. If God does not exists, objective moral values and duties do not exist; 2. Objective moral values and duties do exist; 3. Therefore, God exists. This argument is valid because the conclusion does necessarily follow from the premises.2 Thus, it is sufficient to show that the premises are plausible. Note that it is not enough for the atheist to reject the argument. The atheist has to give good reasons why at least one of the premises is implausible. But I need first to clarify the argument by stating what I mean by the objectivity of moral values and duties. What do We Mean by Objective Moral Values and Duties? First, we need to explain what we mean by moral values and duties. Moral values is about what we call “morally good” or “morally evil.” It is easy to misuse the word ‘good’. For example, one can say that a football play is ‘good’, or that the taste of coffee is ‘bad’, but these words in this context have no moral implications. Moral duties, on the other hand, has to do with obligations, or what is “right” and what is “wrong.” Note that these two notions are different despite the first impression they give. For example, if an old woman is robbed in the street in front of you, then “it is evil to rob a person” (moral value) and “you are obligated to chase the thief” (moral responsibility.) Sometimes, one is confronted by many good choices, but when limited to one, there is “the right thing to do” and “the wrong thing to do.” Other times, one is confronted by many evil choices, but there is again a right action and the wrong action. Second, we need to clarify what I mean by objectivity. To say something is objective (absolute) is to say that it is independent of person’s beliefs and views. That is to say, people’s opinions on the matter does not affect the matter itself. For example, most of 1 These arguments are called “transcendental arguments.” Transcendental arguments are arguments that try to show that some propositions X are necessary conditions for Y . 2 The rule of logical inference is called “modus tollens.” 1 Ratio Christi at Texas A&M us believe that the Earth is round is an objective fact, because whether people believe that or not is irrelevant to the truth value of that statement. The opposite of objectivity is ‘subjectivity’. Thus, to say that something is subjective (relative) is to say that it is dependent on people’s beliefs or opinions. For instance, taste is considered to be a subjective matter. Some people think that coffee tastes good and others think it tastes bad, and the statement “coffee tastes good” is not a fact, for taste depends on people’s preferences. Similarly, objective moral values and duties imply that the question about moral values and duties is independent from people’s beliefs and opinions. For example, to say that the Holocaust is evil is to say that it is evil even if the Nazi thought it was good, and it is evil even if the Nazi won the World War II and brainwashed every person on the planet to believe that it is good. This argument shows that without God, there will be no objective moral values and duties. If moral values and duties exist in that case, they will be relative, subject to individuals’ preferences. But that is not the case: Objective moral values and duties are real. Thus, God exists. According to the Christian view, God is the ground of moral values and duties. This argument, if successful, shows that the atheist cannot live consistently: either he needs to deny both God and objective moral values, or accept both, but the atheist accept one and reject the other. However, the argument faced few objections by atheists. I am going to address the main ones. Moral Nihilism Premise (2) might be challenged. The atheist might affirm that moral values and duties are relative, rather than objective. “Murdering is evil” might be relative to personal opinion, a subject in which people disagree between themselves. “Murdering is evil,” the atheist continues, might be relative to cultures: cultures have different moral values that they appreciate, which contradict the moral values that others hold. There is no reason to hold that (2) is true, let alone plausible. Moral nihilism, even though it is popular among popular atheists, it is not widely believed among philosophers. Philosophers acknowledge the fact that the objectivity of moral values cannot be proven, and they are properly basic belief, but not holding them results in many absurd situations. Is torturing a baby for fun is relatively evil? Is a culture that supports that a morally good culture? Why do we rage when a culture supports murdering innocents? If your friends are moral nihilists, would they think it fine to kill their family and destroy their property? Surely they would think this is evil, but they cannot make such claim for the person who kills and destroys might think it is fine. We cannot prove that moral values and duties are objective, but we can help our atheist friends to see that. Louise Antony puts it this way: “Any argument for moral skepticism will be based upon premises which are less obvious than the existence of objective moral values themselves.” Note also that the objectivity of moral values and duties is not derived from the 2 Ratio Christi at Texas A&M agreement of people. The fact that people agree on “murdering is evil” does not imply “murdering is objectively evil.” Moral realism is a metaphysical principle. Moral realism is as true as the existence of the external world: the external world exists even if most people believe otherwise. Our understanding of moral values and duties might be shaped or changed over time (people believed that slavery is good, and then they rejected it), yet that has no effect of the objectivity of moral values and duties. This situation is similar to the shape of the Earth: people believed that the earth is flat, and then they believed that it is round, and that has no effect whatsoever on the objectivity of the answer to the question “what does the Earth look like?” I hope that it is clear that people’s agreement does not affect moral realism, and that knowing these moral values does not affect their existence. Atheists are Good without God It seems from what is stated previously that objective moral values and duties do exists. Does the atheist in this case challenge the first premise? The atheist might affirm that objective moral values and duties exists, but–in order to avoid the conclusion–say that (1) is false because there are many atheists who are good persons. We can think of all those atheists who live their lives to help those who are in need around the world. There are also many secular organizations that seek to give a hand to those who were subject to natural disasters. To say that atheists are evil is to deny their good work and consider it evil, which is very counter-intuitive because the theist does the exact same actions and consider them to be right. Thus, (1) is not only false, the atheist concludes, but it is obviously false. Unfortunately, many atheists on the Internet raise a similar objection over and over again. This objection shows that the atheist misunderstands what is being stated in premise (1): the non-existence of God implies the non-existence of objective moral values and duties. The premise does not deal with believing in God; it deals with the existence of God. A person can be atheist and does the right moral action without believing in God, and the reason is because God does exist. The condition in (1) is not about believing in God, but the existence of God. Thus, the fact that many atheists do the right moral action and many theists do the wrong moral action does not threaten the truth or the plausibility of the first premise. The atheist has to deny (1) or (2) to avoid the conclusion that God exists. But since (2) seems very plausible, the atheist has to deny (1). In order to do that, one has to give a plausible theory satisfies three conditions: i. explains the existence of objective moral values; ii. explains the existence of objective moral duties; iii. independent from the existence of God. 3 Ratio Christi at Texas A&M Note that the theist cannot prove by mathematical certainty that (1) is true. What the theist has to do is to show that that (1) is plausible by examining every theory concerning moral values and duties the atheist gives case by case. If the atheist cannot give a moral theory, (1) is plausible. So, I will examine briefly the most contemporary theories held by atheist to reject (1). Utilitarianism One view is that moral duties depend on the outcome of that action; the action is right if it maximizes happiness and reduces suffering. This view is called utilitarianism. It is right, for example, for a poor father to steal bread to feed his family if he is utterly unable to provide the money, while it is evil to murder a person because it causes suffering to many people including the victim. Even though one cannot calculate happiness and suffering, it is clear most of the time what is right and what is wrong according to this view. Interestingly, utilitarianism became more popular among atheists after Sam Harris’ book the Moral Landscape. However, this theory, as attractive as it seems, does not account for moral values. We can ask, “why is it good to maximize happiness and reduce suffering?” Why should we not believe that we need to maximize happiness and reduce suffering of monkeys, or ants, instead of humans? It seems that the theory makes a hidden assumption of what is good and what is evil, but it does not account for it. The theist can agree that there are some actions that maximize happiness and reduce suffering, but there is no reason to believe that that is good without justification. In short, utilitarianism fall short in trying to satisfy condition (i). The theory that says “do unto others as you would be done by” has exactly the same problem. Even though it accounts for (ii), it does not account for (i). There is no reason to believe that treating others as one wants to be treated is good. The Evolution of Morality The atheist might say that there objective moral values and duties can be explained away by the theory of evolution. According to this model, our moral values and duties came about through random mutations and natural selection. Thus, our moral intution and sense of being good is a product of evolution, just as our ability of seeing and hearing. Since the theory of evolution does not require God, the atheist might claim, it follows logically that the rise of moral objectivity does not require a divine being. What can we say about this point? There is no problem in asserting that evolution explains moral values and duties! It might be the case that evolution ineed explains moral values and duties as it explains vision and taste, for example. However, evolution does not account for the objectivity of moral values and duties. If the theory of evolution is true, and it happened independent from any external interventions, then it does not explain the rise of objective morality. For our moral values could have been different 4 Ratio Christi at Texas A&M than the ones that other cultures have. That is to say, it might be the case that people who live in Germany are more advance, which allow them to have more advanced moral values and duties. Also, it is possible that if evolution happened again, we would have developed different moral values than today’s, which means that our moral values are contingent, i.e., we happened to have these moral values which could have been different. Thus, evolution per se does not explain both (i) and (ii). Evolution denies (2), which is absurd. Note that this is not the genetic fallacy. We do not say simply that our moral values and duties are subjective simply because we received them by evolution. Rather, we are asserting that evolution is not a justification for the belief in moral values and duties. For example, assume that I say to you that the Earth is round because I read this fact from a cook book. The fact that I read it from a cook book does not disprove the fact that the Earth is round. However, it does not justify it either. Similarly, even if evolution is true, it does not justify moral objectivity. And as a matter of a fact, many philosophers argued that evolution in fact implies the subjectivity of moral knowledge: 4. If human morality is a product of purely natural selection, then objective moral values and duties do not exist; 5. Objective moral values and duties do exist; 6. Therefore, human morality is not a product of purely natural selection. This argument shows that if pure natural evolution accured, then it follows that moralily is illusory. To give an analogy, assume that say to you that the sky is green because I heard it from a teacher. Surely you cannot say that I am right or wrong simply because I heard it from the teacher, but you can say that I am wrong if you can show that what the teacher says is only what is wrong. However, I am not going to defend this argument for it is outside the length of this paper.3 . Euthyphro Dilemma We saw that moral values and duties cannot be objective in the atheistic worldview, but can it be objective in the theistic world view? The atheist says no. Euthyphro dilemma is an old argument given by Euthyphro, an ancient Greek thinker, to Plato. Euthyphro said (goodness is used here as objective moral values and duties): (i) Is goodness good because God chose it to be good? (ii) Or did God chose it because it is good? 3 You can find more detail on this argument in “the Moral Argument” in the Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology. 5 Ratio Christi at Texas A&M If we choose (i), then goodness is arbitrary. If God chose murdering to be good, then God is a source for moral system, but not a good moral system. On the other hand, if we choose (ii), then good is outside of God, i.e., God was bounded by goodness, thus the existence of good is independent of God himself, which makes the existence of God unnecessarity for goodness. In any case, the theist has a problem to solve, implying that (1) is implausible. Can we escape this dilemma? Note that this is not a real dilemma, for the second option is not the negation of the first one. This dilemma gives two options: A and B, but one can choose C or D. If the dilemma was in the form A and not A, then it would have been a real dilemma. We, as a matter of fact, can make a third option and embrace it: God is necessarily good, and that goodness is in God himself. God and goodness are not saperated, if God exsits, goodness exists, otherwise, goodness is illusory. To say that God is necessarily good is to say that God cannot be evil, and to say that God is the source of goodness is to say that goodness is dependent on the existence of God. So, (i) is false because God only choses what matches his nature, which is good. (ii) is also false because goodness is not independent from God. The third option does solve this false dilemma. Note that God did not choose to be morally good, it is part of his definition and nature. God’s goodness is a consequence of his perfection. God has to be good rather than God happened to be good. Similarly, God has to exist rather than God happened to exists, for God is a necessary being. Thus, to ask “why is God necessarily good?” is to ask an incoherent question. This very idea can be found in the Bible. Even though the Bible affirms that God can do everything (Genesis 18:14, Luke 1:37), it affirms also that God cannot lie (Hebrews 6:18, Titus 1:2). The implication the Bible leads to is that God’s nature does not correspond with telling lies. The assertion that the theist is making is completely justified. The theist defines God to be both a concrete object (as apposed to abstract objects) and a necessarily. good. Thus, even if one believes that abstract objects do not exists in reality, that does not affect the theist’s assertion. Also, God did not just happened to be good. Rather, he is the definition of goodness, necessarily. It seems to me that the theist’s theory is successful in providing a ground for such moral goodness, while no atheistic theory does. Conclusion We saw that the moral argument tries to show that without the existence of God, objective moral values and duties are but illusion, which is contrary to the facts. Thus, this argument establish the existence of a morally good being, who is the author of goodness and moral duties. We showed the absurdity of moral relativism, and that whoever does not believe in them cannot live consistently. We examined the most popular ethical theories that are independent from the existence of God and how they fall short in ex6 Ratio Christi at Texas A&M plaining moral values and duties. On the other hand, God as an explanation is successful in grounding moral objectivity–since he is be nature necessarily good. I do think that the moral argument is a sound argument and does indeed justify the belief in God. If one agrees with the premises (1) and (2), they have to agree with (3). 7