Chesterton on War and Peace

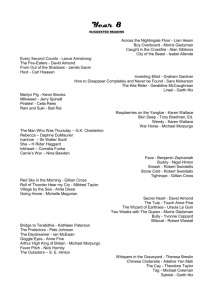

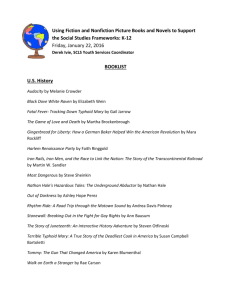

advertisement