Sex, Drugs and Guns: Gonzales v. Raich and

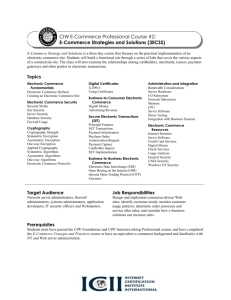

advertisement