SA2001 Handbook 14-15 [1][2]

advertisement

![SA2001 Handbook 14-15 [1][2]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008113248_1-1462bfa25e9511f3a5a6432ca7285930-768x994.png)

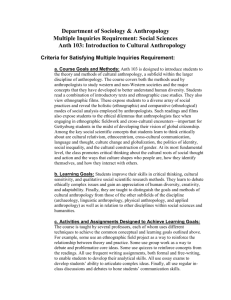

Department of Social Anthropology SA2001 Handbook 2014/15 3.9.14 INTRODUCTION The Second Level Modules in Social Anthropology have a pivotal position in the department's programme. For some students they are the pathway to the Social Anthropology Honours Programme; for others they represent the completion of a quite intensive and sophisticated Sub-­‐

Honours anthropology experience. The department therefore considers that Second Level anthropology constitutes a comprehensive grounding in all basic areas of the discipline. Added to the First Level modules students who accomplish Second Level will have a thorough understanding of the methods and scope of Social Anthropology. They will appreciate its historical roots, how it has built a range of theories concerning human societies and cultures, and the holistic vision by which it explores the relations between economic, political and ideological domains of human life. The learning outcomes of Second Level Anthropology will extend those of First Level. In addition, students who take Second Level will appreciate: 1. The relevance of historical thinking to the discipline of social anthropology, and the relation between theory and ethnographic experience and observation. 2. The relevance of social anthropology in relation to other academic disciplines. 3. How a theoretical understanding the difference between social worlds becomes relevant to the practical accomplishment of life in one's own society, as someone who works, takes place in family life and interacts with many types of people, social institutions and diverse cultural principles. 4. How the Sub-­‐Honours modules lay the foundations for further study at Honours level in Social Anthropology. The Sub-­‐Honours programme grounds students theoretically and gives them the opportunity to develop and explore their interests in Social Anthropology, through ethnographic study as well as by discussing and evaluating particular anthropological issues and problems. 2 SA2001 THE FOUNDATIONS OF HUMAN SOCIAL LIFE This module examines the historical conditions in which modern anthropological practice, concepts and categories have emerged. This includes a survey of the major intellectual developments in the discipline and the major shifts between schools of thought. We focus on the debates that have animated professional anthropology since its inception at the beginning of the twentieth century, including a look at the most recent discussions of anthropological theory and practice. As well as considering competing modes of anthropological analysis, students will be invited to engage with key ethnographic texts. By the end of the course, you should have a clear sense of the history of ideas within professional anthropology (i.e. the relationship between notions such as ‘functionalism’, ‘structural functionalism’, ‘structuralism’, ‘Marxist anthropology’, ‘feminist anthropology’, ‘postcolonialism’ & ‘poststructuralism’), but also a sense of the shifts and development of ethnographic modes of writing. A note on course essays: in addition to readings suggested by lecturers and tutors wherever possible, students should refer to the general texts indicated to in each section and also to those cited for the relevant lectures. Essay topics connect directly to sections of teaching but you must show judgement in how you choose relevant case material for your answer. The more widely and in depth you read, the better your answer is likely to be. KEY READINGS FOR THE MODULE • Barnard, Alan (2000) History and Theory in Anthropology. Cambridge, University Press. • Clifford, James & George Marcus [eds.] (1986) Writing Culture: the poetics and politics of ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press. • Kuper, Adam (1996) Anthropology and Anthropologists. London, Routledge. • Gay y Blasco, Paloma & Wardle, Huon (2006) How to Read Ethnography. London, Routledge ___________________________________________________________________________ Module Convener: Lecturers: Credits: Teaching: Lecture Hour: Tutorials: Workshops: Ethnographic films: Course Assessment: Dr Huon Wardle (hobw). Please address all problems to him. Professor Peter Gow (pgg2), Dr Huon Wardle (hobw), Professor Roy Dilley (rmd), Dr Adam Reed (ader), Dr Stavroula Pipyrou (sp78) 20 Three lectures per week. Plus one workshop/film per week. Also weekly tutorials. Attendance in each component is compulsory. 11am Monday, Tuesday, Thursday & Friday in School 6 These are held WEEKLY in either the department seminar room or in the Arts Building The whole lecture class workshops will be held in School 6. These will be held in one of the class hours of each lecturer’s slot of teaching. These will be shown in one of the class hours of each lecturer’s slot of teaching. They are shown in School 6. Two assessed essays = 30% plus student led project = 10% Two hour examination = 60% 3 An online reading list is available for this module. http://resourcelists.st-­‐andrews.ac.uk/index.html It contains key readings for the course including all those necessary for the tutorials and a core of those required for the essays. Other readings are available in Short Loan and, in some cases, via MMS. 4 SECTION ONE

THE EMERGENCE OF SCIENTIFIC ANTHROPOLOGY WEEKS 1 & 2 Professor Peter Gow, pgg2@st-­‐andrews.ac.uk, 2nd Floor, 71 North Street This section of the course will explore the rise of professionalized fieldwork and the development of theoretical frames within the modern discipline. LECTURE 1: THE INVENTION OF PRIMITIVE SOCIETY We examine the origin of the concept of "primitive society" in the nineteenth century. This includes the concern for the origin of religion, evolutionist thinking and the ranking of societies. • Frazer, James. "The magic art" in The Golden Bough. • Kuper, Adam. The Invention of Primitive Society. • Stocking, George. "Animism, Totemism and Christianity: A Pair of Heterodox Scottish Evolutionists" in After Tylor. LECTURE 2: RIVERS AND THE BEGINNING OF FIELDWORK In this lecture we explore the shift towards scientific methodology in anthropology. We look at the beginnings of fieldwork and its roots in natural science and the naturalistic approach to human thought. • W.H.R. Rivers. "The Primitive Conception of Death" in Richard Slobodin (ed.) W.H.R. Rivers: Pioneer Anthropologist, Psychiatrist of the Ghost Road • Slobodin, Richard. Sections 1-­‐3 from "Work" in Richard Slobodin (ed.) W.H.R. Rivers: Pioneer Anthropologist, Psychiatrist of the Ghost Road • George Stocking. "From the Armchair to the Field: The Darwinian Zoologist as Ethnographer" in After Tylor. LECTURE 3: MALINOWSKI: FIELDWORK AND FUNCTIONALIST ANALYSIS We examine the development of ethnographic research by participant observation. Our attention falls on the density of ethnographic data and on culture as a functional totality. • Malinowski, Bronislaw. "Baloma" in Magic, Science and Religion. • Kuper, Adam. "Malinowski" in Anthropology and Anthropologists. • Stocking, George. "From Fieldwork to Functionalism" in After Tylor. LECTURE 4: RADCLIFFE-­‐BROWN AND STRUCTURAL FUNCTIONALISM This lecture looks at the development of a theory of society; set against history and evolutionism. 5 We look at how comparison was put forward as the key scientific method. • Radcliffe-­‐Brown, A.R. 'Introduction', in A.R. Radcliffe-­‐Brown and D. Forde (eds.) African Systems of Kinship and Marriage, Oxford, OUP. • Kuper, Adam. "Radcliffe-­‐Brown" and "The Thirties and the Forties" in Anthropology and Anthropologists. • Fortes, M. 'Introduction', in J. Goody (ed.) The Developmental Cycle in Domestic Groups. LECTURE 5: LÉVI-­‐STRAUSS We look at the move to the human mind, and the examination of nature and culture. This includes examining what comparison says about the nature of what it is to be human. • Lévi-­‐Strauss, C. "Race and History" in Structural Anthropology. • Leach, Edmund. "Rethinking Anthropology" in Rethinking Anthropology. • Mary Douglas. "If the Dogon ..." in Implicit Meanings. LECTURE 6: THE ARRIVAL OF CULTURE Finally, we look at the arrival, from the USA, of the concept of culture. Do all humans have culture? This includes the shift away from society towards the person and culture. • Wagner, Roy. "Chapter 1: The assumption of culture" in The Invention of Culture. • Strathern, M. "No nature, no culture" in C. McCormack and M. Strathern (eds) Nature, Culture and Gender. • Fortes, M. "The concept of the person" in Religion, morality and the person. ETHNOGRAPHIC FILM—STRANGERS ABROAD 3: WH RIVERS-­‐EVERYTHING IS RELATIVES In this celebration of one of anthropology's foremost ancestors, the life and work of Rivers are clearly explained. In particular, the documentary outlines his genealogical method for understanding kinship, returning to the same locations visited by Rivers to test his theories out against contemporary realities. WORKSHOP Topic to ponder: Now we all know about, and even celebrate, "cultural differences". This popular understanding of "culture" has a very long history in anthropology, and makes it hard for us now to understand just how difficult it was to move from racist evolutionism to modern anthropology. 6 SECTION TWO SOCIETY AS A DYNAMIC SYSTEM WEEKS 3-­‐5 Dr Huon Wardle, hobw@st-­‐andrews.ac.uk, Room 20, United College TOPIC 1: STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION: THE PROFESSIONALISATION OF SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY On the idea of ‘function’ At its simplest, functionalism describes a question addressed to particular ideas and behaviours; ‘socially speaking, what use are these practices for these people?’ The first lectures for this part of the course deal with the emergence and refinement of the ideas of structure and function in social anthropology from the 1930s to the mid-­‐1950s. We look initially at some of the classic functionalist ethnographies of the 1930s. These texts demonstrate a focus on small-­‐scale (often island-­‐based) societies and a common aim of showing how social roles, rights, responsibilities, institutions and behaviours are coordinated and respond functionally to basic human needs. The emphasis in these functionalist works is on methodological induction – collecting as large a quantity of observations as possible in order to arrive at generalisations. Functionalism as a movement is closely connected to the seminars run by Malinowski at the LSE during the 1930s. Gellner has distinguished function as the method of collecting data with a view to the social usefulness criterion, from function as a doctrine (the principle that everything in a society has a ‘purpose’ within the whole). He argues that the latter assumption is suspect, while the former idea has enduring value. Diffusionism As an approach, functionalism is in part a reaction against the historical speculation characteristic of evolutionist and diffusionist writing. A good example of the diffusionist approach is this article by WHR Rivers. Rivers, W.H.R. ‘Massage in Melanesia’ in B. Goode et al. (ed.) A Reader in Medical Anthropology. Ch. 1. Function Kuper, A. 1979. Anthropology and Anthropologists. Chapter 3 (‘the 1930s and 1940s’). Firth, R. 1936. We the Tikopia. (Esp. Chapter VI). Fortune, R. 1932. Sorcerers of Dobu. Richards, A. 1932. Hunger and Work in a Savage Tribe. Especially Ch. 1.section 4. Malinowski, B. 1935. Coral Gardens and Their Magic, Volume II, ‘The Sociological Function of Magic’. • Fei, Hsiao-­‐Tung (Xiaotong). 1938. Peasant Life in China. • Clarke, E. 1957. My Mother Who Fathered Me. •

•

•

•

•

On the idea of ‘social structure’ 7 Structural functionalism analyses society as a system of interrelating parts asking the question ‘what is the function of X practice in relation to the overall social structure?’ The approach, drawing inspiration from Radcliffe-­‐Brown, comes to the fore in the 1940s, as a more abstract anthropology also emerges. Radcliffe-­‐Brown had placed weight on a view of society as akin to an articulated social organism (an idea of Herbert Spencer’s). The emphasis in structural functionalist texts is more analytical and deductive –models and holistic social logics are applied to a body of observations. Evans-­‐Pritchard’s The Nuer represents a high point of this development. Structural Functionalism • Radcliffe-­‐Brown, A. 1952. Structure and Function in Primitive Society. Intro. Chap 1. • Metcalf, P. 2005. Anthropology: The Basics. Chapters 3 and 4. • Wilson, M. 1951. ‘Witch-­‐beliefs and Social Structure’ American Journal of Sociology, 56(3):307-­‐

13. * (Or chapter 22 in Marwick M. (ed) Witchcraft and Sorcery). • Evans-­‐Pritchard, E. 1940. The Nuer. • Kaberrry, P. 1952. Women of the Grassfields. http://www.era.anthropology.ac.uk/Kaberry/Kaberry_text/ • Fortes, M. (et al, eds) 1940. African Political Systems. • [1959]1971. ‘Primitive Kinship’ in Spradley, J. (ed) Conformity and Conflict. Additional Readings • Gay y Blasco, P. and Wardle, H. 2006. How to read Ethnography. Chapter 3 (‘Relationships and Meanings’). • Gellner, E. 1987. The Concept of Kinship. Chapter 7 (‘Sociology and Social • Anthropology’). • Goody, J. 1995. The Expansive Moment. • Grimshaw, A. and K. Hart. 1993. Anthropology and the Crisis of the Intellectuals. • Hsueh-­‐Chin, T. [C.18]1917. Dream of the Red Chamber. • Leach, E. The Essential Edmund Leach. Vol. 1, chapter 1.8 (‘Social Anthropology: A Natural Science of Society?’) • Lienhardt, G. 1966. Social Anthropology. Chapter 5 (‘Kinship and Affinity’). • Metcalf, P. 2005. Anthropology: The Basics. Chapters 3 and 4. • Thompson, D. [1917]1994. On Growth and Form. • Wardle, H. and P. Gay y Blasco. 2011. ‘Ethnography and an Ethnography in the Human Conversation’ Anthropologica 53(1):117-­‐129. N.B. All readings marked * are available electronically through the online catalogue. Lecture themes: (1) funtionalism, holism, synchronicism; (2) kinship as an articulating structure; (3) The ‘doctrine’ of structural functionalism – society as an ‘organism’; (4) empiricism and rationalism –relativism and universalism. ETHNOGRAPHIC FILM – THE NUER TOPIC 2: THE PROBLEM WITH ‘TIME’: PROCESS, CHANGE AND TRANSFORMATION While anthropology came to be defined by its fieldwork-­‐based, holistic, synchronic emphases during 1930-­‐1955, criticisms of the functionalist approach appear quite early; from, amongst others, Gregory Bateson whose early affiliations were to Rivers and Haddon in Cambridge. Anthropologists such as Gluckman and Barth began to build situational and individualistic diversity into their accounts that challenged the ‘social organic’ view of Radcliffe-­‐Brown. Firth’s work on ‘social 8 organisation’ also critiques the rigidity of social structure as explanation. Edmund Leach’s Political Systems of Highland Burma is a key moment in this revision of structural functionalist orthodoxy, marking the opening up, from the 1960s onwards, of a more intellectualist, less empirically focused movement – structuralism. Time, change and history in anthropology • Leach, E. 1954. Political Systems of Highland Burma. • Firth, R. 1955. ‘Some Principles of Social Organization’. Journal of the Royal • Anthropological Institute, 85(1/2):1-­‐18. * • Evans-­‐Pritchard, E. 1950. ‘Social Anthropology: Past and Present’ Man, • L(198):118-­‐124. * • Fortes, M. [1957]1983. Oedipus and Job in West African Religion. • Goody, J. (ed). 1971. The Developmental Cycle of Domestic Groups. (Introduction by Meyer Fortes). • Sahlins, M. 1963. ‘Poor Man, Rich Man, Big Man, Chief’. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 5:285-­‐303. * Additional Readings • Achebe, C. 1958. Things Fall Apart. • Bateson, G. 1936. Naven. • Burridge, K. 1960. Mambu. • Fortune, R. 1935. Manus Religion. • Gay y Blasco, P. and Wardle, H. 2006. How to read Ethnography. Chapter 8 (‘Big Conversations’) • Gellner, E. 1958. ‘Time and Social Theory’. Mind, 67:182-­‐202. * (or The Concept of Kinship, chapter 6) • Gluckman, M. [1940]1958. Analysis of a Social Situation in Modern Zululand. • Lipset, D. 1982. Gregory Bateson: Legacy of A Scientist. • Nadel, S.F. 1942. A Black Byzantium. • _______1951. The Foundations of Social Anthropology. (ch. VI, ‘Institutions’). • Schapera, I. 1962. ‘Should Anthropologists be Historians? Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 92(2):143-­‐56. * • Wardle, H. 1999. ‘Gregory Bateson’s Lost World’. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 35(4):379-­‐389. N.B. All readings marked * are available electronically through the online catalogue. Lecture themes: (1) the problem of the time factor; (2) radical change; (3) cyclical and processual change; (4) enduring legacies ETHNOGRAPHIC FILM Lost Kingdoms of Africa: The Zulu Kingdom 9 TOPIC 3: HUMAN UNIVERSALS RECONSIDERED – STRUCTURALISM AND THE INTELLECTUALIST TURN The period in the development of social anthropology from the late 50s onwards is closely associated with a renewed interest in human universals. In this climate, the Structuralisme protagonised by Claude Levi-­‐Strauss (as distinct from British Structural Functionalism) gained ascendency. Structuralism became an intellectualist movement focused on how the human mind supplies the bases of socio-­‐cultural commonality and difference. Levi-­‐Strauss’ work was championed (sometimes equivocally) by Edmund Leach in British circles. The work of Mary Douglas, Gregory Bateson, Victor Turner and Robin Horton take similarly universalizing stances but with different emphases. In the United States, work on universals of colour perception, inter alia, correspond to the expanded scope for a scientific anthropology in this period. These lectures will focus on two debatably ‘universal’ properties of human thought and sociality including the tendency toward reciprocity (exchange/The Gift). This part of the discussion requires us to review the different pathways anthropology had taken up to now in its three main strongholds – Britain, France and the United States. On the idea of ‘structure’ and structuralism Levi-­‐Straussian structuralism describes a move toward a significantly more abstract idea of culture. Levi-­‐Strauss argued that culture is essentially a cognitive phenomenon. Rather than the British emphasis on fieldwork in small-­‐scale societies and the empirical study and modelling of social practices, the aim of structuralist inquiry is to explore universal tendencies of the human mind to generate culture. Levi-­‐Strauss looked first at kinship structures then at mythology to find clues about these universal potentials of the human mind. • Leach, E. 1976. Culture and Communication. • Leach, E. 1972. ‘Anthopological Aspects of Language: Animal Words and Verbal Abuse’ in P. Miranda (ed.) Levi-­‐Strauss. • Leach, E. 1970. Levi-­‐Strauss. • Lévi-­‐Strauss. 1963. Structural Anthropology. • Lévi-­‐Strauss. 1973. Tristes Tropiques. • Metcalf, P. 2005. Anthropology, the Basics. Ch 6. Gift, reciprocity, exchange: • Graeber, D. ‘On the Moral Ground of Economic Relations: A Maussian Approach’. English version of a paper for special issue of La Revue du Mauss. K. Hart (ed.) (forthcoming). • Guyer, J. ‘The True Gift: Thoughts on L’annee Sociologique Edition of 1923/24’. English version of a paper for La Revue du Mauss K. Hart (ed.) (forthcoming). • Levi-­‐Strauss, C. 1949. The Elementary Structures of Kinship. Volume I, Ch V. • Mauss, M. 1924. The Gift. • Sigaud, L. 2002. ‘The Vicissitudes of the Gift’ Social Anthropology 10(3):335-­‐ • 358. • Tarde, G. 1899. Social Laws: An Outline of Sociology. Chapter II ('The Opposition of Phenomena') Available for free at the Open Library 10 WORKSHOP The words 'structure' and 'structuralism' strike fear into the heart of even the most hardy anthropology student. This session will act as a recap session. What is a structure? How are social structures formed? what is function? what is the difference between British Structure and French Structuralism? 11 SECTION THREE

MEANING AND RATIONALITY OF SOCIAL LIFE WEEKS 6 & 7 PLEASE NOTE: Classes will take place on Raisin Monday as usual (20/10/14) Professor Roy Dilley rmd@st-­‐andrews.ac.uk Room 21, United College MAKING SENSE OF RITUAL. FROM FUNCTION TO MEANING For a general discussion of issues raised in this two-­‐week course of lectures, see B. Morris, Anthropological Studies of Religion, Cambridge U. P. 1987*. In addition, two useful collections of articles and chapters on relevant themes: see M. Lambek (ed.), A Reader in the Anthropology of Religion (2002)*, and W. Lessa & E. Vogt (eds), Reader in Comparative Religion (1979)*. * means the book is on short loan in the University Library ** means the article is available electronically through JSTOR The series of lectures in Week 7 will outline a selection of developments in anthropological thought that took the discipline beyond the functionalist paradigm of the 1930s and 1940s. We start off by looking at the classic issue of rites of passage, but instead of regarding them as mechanisms for the management of the transition of persons from one social status to another, they are now viewed as sites for the negotiation of conflict, dissent and rebellion. The idea of the primary human experience of those undergoing ritual transformation is also examined. By contrast, structuralist approaches to ritual are presented next, and these attempt to locate an underlying cultural logic that is the basis for their social organisation. This perspective is, however, critically examined in the final lecture, in which the problem of native knowledge and understanding of ritual activity is raised. This approach is contrasted with those views that seek a logic in social organisation which links ritual symbols and action into an overarching conceptual structure. LECTURE 1. RITES OF PASSAGE: BEYOND FUNCTIONALISM • A. van Gennep. The Rites of Passage [1908], London: RKP 1965 • V. Turner. The Ritual Process [1969], Harmondsworth: Penguin 1974* • Schism and Continuity in an African Society, Manchester U.P. 1957* • M. Gluckman (ed.). Essays on the Ritual of Social Relations, Manchester U. P. 1962* LECTURE 2. STRUCTURALIST APPROACHES TO RITUAL • L. de Heusch, ‘Heat, Physiology and Cosmogony: Rites de Passage among the Thonga’ in I Karp and C. Bird (eds) Explorations in African Systems of Thought, Washington DC 1980, pp. 27-­‐43.* 12 • E. Leach. Culture and Communication, Cambridge U. P. 1976* • C. Lévi-­‐Strauss. Structural Anthropology, Harmondsworth: Penguin 1963* LECTURE 3. LOCAL KNOWLEDGE AND THE PERFORMANCE OF RITUAL • C. Bell. Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice, esp. chp. 2, Oxford U.P. 1992.* • G. Lewis. Day of Shining Red: An Essay on Understanding Ritual, Cambridge U. P. 1980 • S. Tambiah, ‘A Performance Approach to Ritual’, Proceedings of the British Academy, LXV (1979), pp113-­‐69. THE RATIONALITY OF RELIGIOUS THOUGHT. INTELLECTUALIST, CONTEXTUALIST AND SYMBOLIST APPROACHES The lectures in Week 8 examine the problem of how anthropologists deal with religious thought in other societies. Expressions of such religious thought are manifested in types of social activity or in statements made by local actors, the meaning or sense of which is not obviously apparent to the outside observer. These lectures investigate the ways in which anthropologists have sought to give sense to religious thought and practice. How can they be seen to intelligible, or even rational? Varying views on such questions give rise to a debate amongst anthropologists about the extent to which religious thought could be seen to be akin to our own conceptions of science on the one hand, or of art, poetry and literature on the other. Three different approaches to this debate will be outlined over the course of the week’s lectures. LECTURE 4. THE INTELLECTUALIST APPROACH • E. B. Tylor. ‘Religion in Primitive Culture’ [1871], reprinted in M. Lambek (ed.), A Reader in the Anthropology of Religion, 2002* • L. Lévy-­‐Bruhl. How Natives Think, London: Allen & Unwin 1926 • R. Horton. ‘Ritual Man in Africa’, in Africa Vol. 34 [1964], also reprinted in W. Lessa & E. Vogt (eds), Reader in Comparative Religion, 1979*/** • ‘African Traditional Thought and Western Science’, in Africa Vol. 37 [1967], also reprinted in B. Wilson (ed.) Rationality, Oxford: Blackwell 1970*/** See also, J. Skorupski, Theory and Symbol [1976], in which he discusses this and other approaches from a philosopher’s viewpoint. LECTURE 5. THE CONTEXTUALIST APPROACH • E. Evans-­‐Pritchard. ‘The Problem of Symbols’, chp 5. of Nuer Religion [1956], reprinted in M. Lambek (ed.), A Reader in the Anthropology of Religion, 2002* • ‘The Notion of Witchcraft Explains Unfortunate Events’, Part 1, Chp 4, Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande[1937] (Chp 2 in abridged edition, 1976), also reprinted in W. Lessa & E. • Vogt (eds), Reader in Comparative Religion, 1979* • Theories of Primitive Religion, Oxford U.P. 1965 • E. Gellner. ‘Concepts and Society’, in B. Wilson (ed.) Rationality, Oxford: Blackwell 1970* LECTURE 6. THE SYMBOLIST APPROACH • J. Beattie. ‘Ritual and Social Change’, in Man [JRAI], Vol 1 (N.S.), 1966, 60-­‐74** • ‘On Understanding Ritual’, in B. Wilson (ed.) Rationality, Oxford: Blackwell 1970, pp.240-­‐68.* 13 • ‘Objectivity and Social Anthropology’, in S. Brown (ed.), Objectivity and Social Divergence, Cambridge U. P. 1984.* • G. Lienhart. ‘The Control of Experience: Symbolic Action’, chp 7 of his book Divinity and Experience, reprinted in M. Lambek (ed.), A Reader in the Anthropology of Religion, 2002* ETHNOGRAPHIC FILM – WITCHCRAFT AMONG THE AZANDE, ANDRÉ SINGER AND JOHN RYLE A programme in the Granada TV’s series ‘Disappearing World’, this film examines witchcraft beliefs and oracular practice among the Azande, in an attempt to corroborate Evans-­‐Pritchard’s ethnography of some 50 years earlier. The film illustrates the continued importance of witchcraft today, and gives us an intimate and personal picture of its place in the lives of a number of Zande individuals. It remains a major danger to human life, and effective means of diagnosing its effects are crucial. The various kinds of oracle used by the Azande are the means by which the causes of misfortune can be identified. One of the features of social life that has changed since Evans-­‐

Pritchard’s time is the introduction of Catholicism into the area, and this has created tensions and divisions of opinion in Zande society about the place of witchcraft beliefs in relation to the Church. Yet, older people see the young abandoning their traditional moral and cultural values, and here they come to regard the Church and witchcraft beliefs as sharing a set of common values to guide the younger generation. WORKSHOP – TO BE ANNOUNCED 14 SECTION FOUR ANTHROPOLOGY’S REFLEXIVE TURN WEEKS 8 & 9 Dr Adam Reed, ader@st-­‐andrews.ac.uk, Room 56, United College (Quad) This section explores developments in anthropology and ethnographic writing towards the end of twentieth century. It begins by examining the contribution of feminist anthropology to the discipline. Then the course examines what is known as the ‘reflexive turn’, the increasing attention paid since the 1980s to the mediating role of text, which includes a new awareness of the responsibilities of anthropologists as text-­‐producers. These debates centre round issues of representation. How does language structure description? Which voices and what aspects of the fieldwork experience are typically left out of ethnography? Attention focuses here as much on the culture of anthropology as on the societies anthropologists describe. One of the important outcomes of this disciplinary reflection is a whole range of new styles of ethnographic writing, all of which aim to better capture the nature of social and cultural realities. LECTURE 1: FEMINIST ANTHROPOLOGY: LOST VOICES In the 1970s feminist anthropology began to consider why it was that women were marginalized in most ethnographic accounts. Much of these early debates centred round issues of power and control over female labour. In response, some anthropologists consciously strove to provide space for female subjects’ voices and biographies in their ethnographies; we explore some examples. • Ardener, Edwin. 1972. ‘Belief and the problem of women’, in The Interpretation of Ritual. La Fontaine [ed]. Tavistock (photocopy on short loan). • Rosaldo, M & Lamphere, L. 1974. [eds]. Women, Culture and Society. Stanford University Press [especially introduction (book on short loan)]. • Ortner, S & Whitehead, H [eds]. 1981. Sexual Meanings: the cultural construction of gender and sexuality. Cambridge University Press (book on short loan). • Shostak, Marjorie. 1981. Nisa: the life and words of a !Kung woman. Allen Lane [especially Introduction & chp 4 (book on short loan)] LECTURE 2: FEMINIST ANTHROPOLOGY: NATURE & CULTURE Here we examine the move within feminist anthropology away from straightforward recovering of the position of women in cultures and towards broader critique of anthropological knowledge practice. In particular, attention falls on a series of dualities or oppositions: Nature/Culture, Individual/Society, through which categories such as ‘male’ and ‘female’ are typically understood and constrained. Cultures and societies are revealed to not necessarily share these dominant gendered assumptions. 15 • Strathern, Marilyn. 1980. ‘No Nature, No Culture: the Hagen Case’. In C. MacCormack & M. Strathern (eds.). Nature, Culture and Gender. Cambridge University Press (book on short loan & Readers Pack). • Moore, Henrietta. 1988. Feminism and Anthropology. Polity [especially chps 1 & 2 (book on short loan & Readers Pack)]. • Strathern, Marilyn. 1988. Gender of the Gift. California University Press [especially chapters 3 & 4) (book on short loan). • Moore, Henrietta: 1986. Space, Text and Gender : an anthropological study of the Marakwet of Kenya. Cambridge University Press [especially chps 1, 4 & 9 (book on short loan)]. • Gillison, Gillian. 1980. ‘Images of Nature in Gimi Thought’. In C. MacCormack & M. Strathern (eds.). Nature, Culture and Gender. Cambridge University Press (book on short loan). LECTURE 3: FEMINIST ANTHROPOLOGY: THIRD SEX & BEYOND Here we discuss the development of performance theories of gender and in particular the rise of challenges to the male/female positioning of sexuality in anthropological studies. Ideas such as ‘third sex’ are explored in conjunction with illustrative ethnographic accounts. After the emergence of women as fully developed ethnographic subjects, we now get studies of gay, lesbian and transsexual subjectivities. • Herdt, Gilbert. 1993. Third sex, third gender: beyond sexual dimorphism in culture and history. Zone books [especially Introduction & chps 5 & 10 (book on short loan & Readers Pack)]. • Kulick, Don. 1998. Travesti : sex, gender, and culture among Brazilian transgendered prostitutes. University of Chicago Press [especially Introduction & chps 2 & 5 (book on short loan)]. • Boellstorff, Tom. 2005. The Gay Archipelago : Sexuality and Nation in Indonesia. Princeton University Press [especially chapter chps 1, 4 & 8 (book on short loan)]. • Green Sarah. 1997. Urban amazons : lesbian feminism and beyond in the gender, sexuality, and identity battles of London [especially Introduction & chps 1 & 6 (book on short loan)]. • Sullivan, Nikki. 2003. A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory. Edinburgh University Press [especially chps 1, 3 & 5 (book on short loan)]. • Laqueur, Thomas. 2003. Solitary Sex. Zone Books [especially chps 1 & 6 (book on short loan)]. LECTURE 4: DIALOGIC ANTHROPOLOGY We examine the emergence of quasi-­‐journal style ethnographies, which may include rich memoirs of fieldwork and long quoted dialogues between anthropologist and favoured informant. These are produced to critique the authority of scientific description and fieldwork practice, to question the basis on which anthropologists claim to know the peoples they work with. Anthropology is presented as suffering a crisis of confidence. • Rabinow, Paul. 1977. Reflections on fieldwork in Morocco. Berkley: University of California Press [especially chp 4: ‘Entering’ & Conclusion (book on short loan & Readers Pack)] • Crapanzano, Vincent. 1980. Tuhami, portrait of a Moroccan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press [especially Introduction & Part One (book on short loan)]. • Dwyer, Kevin. 1982. Moroccan dialogues : anthropology in question. Waveland Press [especially chps 1, 12 & 13 (book on short loan)] • Geertz, Clifford. 1988. Works and Lives: the Anthropologist as Author. Cambridge, Polity [chp 4: (photocopy & book on short loan)] 16 LECTURE 5: WRITING CULTURE In this lecture, we look at the culmination of all these critiques: the ‘writing culture’ debates of the late 1980s. Anthropologists turned to examine their own practices as text-­‐producers and the mediatory role of language in acts of ethnographic description. This included examining the textual strategies by which anthropologists in the past persuaded readers of their authority to describe other cultures and the identification of conventional stories or allegories in anthropological texts. The discipline appeared to suffer a crisis of representation. • Marcus. George & Clifford, James 1986 (eds) Writing Culture. The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. University of California Press [especially Clifford ‘Introduction: partial truths’ & ‘On ethnographic allegory’ (book on short loan & Readers Pack)) • Marcus, G & Fisher, M. 1986. Anthropology as Cultural Critique: an Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences. University of Chicago Press [especially chp 1: ‘A crisis of representation in the human sciences’ (book on short loan)]. • Geertz, Clifford. 1988. Works and Lives: the Anthropologist as Author. Cambridge, Polity [chp 1: ‘Being There’ (book on short loan & Readers Pack]. • Behar, Ruth & Gordon, Deborah. 1995. (eds). Women Writing Culture. University of California Press [especially Introduction (book on short loan)]. LECTURE 6: NEW ETHNOGRAPHY 1: AMBIGUITY While the reflexive turn highlighted the limits of the anthropological project, it also provided an impetus to new modes of ethnographic writing. Using the insights of the ‘writing culture’ debates, anthropologists in 1990s devised new textual strategies for better capturing cultural realities. In this lecture, we focus on attempts to depict the fluid, dynamic and ambiguous qualities of cultures and societies. • Clifford, James. 1988. The Predicament of Culture. Twentieth Century ethnography, literature and art. Harvard University Press [Introduction & chps: 1 & 4 (book on short loan)]. • Stewart, Kathleen. 1996. A Space on the Side of the Road: cultural poetics in an ‘Other’ America. Princeton University Press [chps: 1 & 3 (book on short loan)]. • Taussig, Michael. 1992. The Nervous System. Routledge [chps: 1 & 3 (book on short loan)]. • Pratt, M. 1992. Imperial Eyes. Routledge [Introduction (book on short loan)]. LECTURE 7: NEW ETHNOGRAPHY 2: INTERSECTIONS

This lecture looks at a different outcome of the reflexive turn. It explores the attempt to critique the pervasiveness of idioms of dwelling in anthropological description. New ethnographies arise which seek to depict the fieldwork location as a site of transience or comings and goings as well as a site of residence. Both the anthropologist and the people he/she works with are recognised to travel as well as dwell. • Clifford, James. 1997. Routes: travel and translation in the late twentieth century. Harvard University Press [chps 1 & 3 (book on short loan & Readers Pack)]. • Tsing, Anna. 1993. In the Realm of the Diamond Queen: marginality in an out-­‐of-­‐the-­‐way place. Princeton University Press [Opening & chps: 4, 5 & 6 (book on short loan & Readers Pack)]. • Rosaldo, Renato. 1989. Culture and Truth: the remaking of social analysis. Routledge [chp: 1 (book on short loan)]. 17 • Reed, Adam. 2003. Papua New Guinea’s Last Place: experiences of constraint in a postcolonial prison. Berghahn: Oxford [especially chp: 2 (book on short loan)]. ETHNOGRAPHIC FILM—CANNIBAL TOURS One of the most important documentaries of recent years, this film gives an eye-­‐opening account of tourism on the Sepik River, Papua New Guinea. It raises important questions about how 'we' encounter the Other and the uncomfortable link between anthropology and tourism and between observation and voyeurism. Readings for Essay 2 – Question 8 • Ardener, Edwin. 1972. ‘Belief and the problem of women’, in The Interpretation of Ritual. La Fontaine [ed]. Tavistock (photocopy on short loan). • Moore, Henrietta. 1988. Feminism and Anthropology. Polity [especially chps 1 & 2]. • Strathern, Marilyn. 1988. Gender of the Gift. California University Press [especially chapters 3 & 4). • Strathern, Marilyn. 1980. ‘No Nature, No Culture: the Hagen Case’. In C. MacCormack & M. Strathern (eds.). Nature, Culture and Gender. Cambridge University Press (book on short loan & Readers Pack). • Moore, Henrietta: 1986. Space, Text and Gender : an anthropological study of the Marakwet of Kenya. Cambridge University Press [especially chps 1, 4 & 9 (book on short loan)]. • Rosaldo, M & Lamphere, L. 1974. [eds]. Women, Culture and Society. Stanford University Press [especially introduction (book on short loan)]. • Ortner, S & Whitehead, H [eds]. 1981. Sexual Meanings: the cultural construction of gender and sexuality. Cambridge University Press (book on short loan). • Herdt, Gilbert. 1993. Third sex, third gender : beyond sexual dimorphism in culture and history. Zone books [especially Introduction & chps 5 & 10]. Readings for Essay 2 – Question 9 • Marcus. George & Clifford, James 1986 (eds) Writing Culture. The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. University of California Press [especially Clifford ‘Introduction: partial truths’ & ‘On ethnographic allegory’] • Marcus, G & Fisher, M. 1986. Anthropology as Cultural Critique: an Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences. University of Chicago Press [especially chp 1: ‘A crisis of representation in the human sciences’]. • Geertz, Clifford. 1988. Works and Lives: the Anthropologist as Author. Cambridge, Polity [chp 1: ‘Being There’]. • Clifford, James. 1988. The Predicament of Culture. Twentieth Century ethnography, literature and art. Harvard University Press [Introduction & chps: 1 & 4 (book on short loan)]. • Taussig, Michael. 1992. The Nervous System. Routledge [chps: 1 & 3 (book on short loan)]. • Rosaldo, Renato. 1989. Culture and Truth: the remaking of social analysis. Routledge [chp: 1 (book on short loan)]. 18 SECTION FIVE ANTHROPOLOGY IN THE CONTEMPORARY WORLD WEEKS 10 & 11 Dr Stavroula Pipyrou sp78@st-­‐andrews.ac.uk 1st Floor, 71 North Street LECTURE 1: ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE MILITARY In recent times, wars and armed conflicts have affected large parts of the world. There have been many military interventions on the part of Western organisations and coalitions, and many other countries are also still suffering the effects of open or silenced warfare between states’ armies and paramilitary organisations or guerrilla movements. There has been an increased presence of the military in the daily lives of people, and voices have emerged which suggest that we are undergoing a global process of militarisation. But, is this or should this be a concern for anthropologists? This debate has been made famous by ‘Project Camelot’ and more recently the US ‘Human Terrain Systems’ programme. • Ben-­‐Ari, E. 2008. War, the military and militarization around the globe. Social Anthropology 16, 1: 90-­‐98. • Frese, P. and M. Harrell. 2003. Anthropology and the United States Military: coming of age in the 21st century. Palgrave MacMillan: New York. • Galtung, J. 1967. Scientific Colonialism. In Transition, Number 30, pp: 10-­‐15. • Gonzalez, R. J. 2007. Phoenix reborn? The rise of the 'Human Terrain System'. In Anthropology Today 23(6): 21-­‐22 • Gonzalez, R. J. 2009. On ‘tribes’ and ‘bribes’: ‘Iraq tribal study’, al-­‐Anbar’s awakening, and social science. Focaal 53:105-­‐16. • Gonzalez, R. J. 2009. Going ‘tribal’: Notes on pacification in the 21st century. Anthropology Today 25: 15-­‐19. • McFate, M. 2005. Anthropology and Counterinsurgency: the strange story of their curious relationship. In Military Review. LECTURE 2: ANTHROPOLOGY, RADICAL POLITICS AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS In 2009, the University of East London dismissed Chris Knight from his post as professor of anthropology over a dispute that originated over his controversial involvement in protests against the G20. Knight and his colleagues in the Radical Anthropology Group have in recent years raised concerns about anthropology’s relationship with international capitalism and its associated political structures. We question the role of advocacy in social anthropology – both within colonial and ‘Western’ settings – and relate such protests to the conditions facing anthropologists as they conduct research in the current economic climate of distress and austerity. • Graeber, D. 2007. Revolution in Reverse. Radical Anthropology Journal 1: 6-­‐16. • Graeber, D. 2004. Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press. 19 • MacClancy, J. 2002. Exotic No More: Anthropology on the Front Lines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. • Vradis, A. and D. Dalakoglou. (eds.). 2011. Revolt and Crisis in Greece: Between a Present yet to Pass and a Future still to Come. Oakland: AK Press. • For a background on the Chris Knight affair visit http://www.chrisknight.co.uk/ LECTURE 3: ‘ILLEGAL ORGANISATIONS’ Some anthropologists, either deliberately or inadvertently, find themselves conducting research among people involved in ‘illegal’ activities. This may range from street gangs and drug dealers to the Italian mafia. Is it appropriate for anthropologists to put themselves at risk by conducting such research and how far should they take ‘participant observation’? Surely as anthropology is the study of human diversity, people involved in illegal activities should be able to have their stories told (their perspectives) as well as those in the position of mainstream socio-­‐political power. • Blok, A. 1974. The Mafia of a Sicilian Village, 1860-­‐1960: a study of violent peasant entrepreneurs. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. • Bourgois, P. 1989. Crack in Spanish Harlem: Culture and Economy in the Inner City. Anthropology Today, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 6-­‐11. • Bourgois, P. 2003. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. New York: Cambridge University Press. • Catanzaro, R. 1988. Men of Respect: a social history of the Sicilian Mafia. New York: The Free Press. • Chubb, J. 1996. The Mafia, the Market and the State in Italy and Russia. In Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Volume 1, Issue 2 Spring 1996, pp. 273 – 291. • Pipyrou, S. 2010. Narrative of a Fine Day: on the cultural appropriation of violence. Anthropology reviews: dissent and cultural politics (ARDAC). 1 (1). pp. 33-­‐35. (available online). • Schneider, J. and P. Schneider, 2002. The Mafia and al-­‐Qaeda: Violent and Secretive Organizations in Comparative and Historical Perspective. In American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 104, No. 3 (Sep., 2002), pp. 776-­‐782. • Schneider, J. and P. Schneider. 2003. Reversible Destiny: Mafia, Antimafia, and the Struggle for Palermo. Berkeley: University of California Press. FRIDAY FILM: TBC LECTURE 4: GLOBAL ECONOMIC UNCERTAINTY As societies around the world experience the most significant time of economic turmoil for generations, how do anthropologists approach the study of intertwining global and local cultural systems? Often definitions of the current economic crisis focus on macro-­‐scale accounts of dramatic bailouts and incomprehensible numbers. Such grand definitions seem to have become complacent and over-­‐ritualised. How can anthropologists study the effects of such a complex and ambiguous time of uncertainty on the everyday lives of subjects in a variety of cultural contexts? • Bowles, P. 2002. Asia’s Post-­‐Crisis Regionalism: bringing the state back in, keeping the (United) States out. In Review of International Political Economy, Volume 9, Number 2, pp: 230-­‐256. • Bratsis, P. 2003. Corrupt Compared to What: Greece, capitalist interests, and the specular purity of the State. London: London School of Economics and Political Science. (available online). 20 • Goddard, V. 2006. This is history: Nation and experience in times of crisis – Argentina 2001. In History and Anthropology, Volume 17, Number 3, pp: 267-­‐286. • Goddard, V. 2010. Two Sides of the Same Coin? World citizenship and local crisis in Argentina. In Theodossopoulos, D. and E. Kirtsoglou. (eds.). 2010. United in Discontent: local responses to cosmopolitanism and globalization. Oxford: Berghahn Books. • Hart, K. and H. Ortiz. 2008. Anthropology in the financial crisis. In Anthropology Today, Volume 24, Number 6, pp: 1-­‐3. • Knight, D. M. 2012. Cultural Proximity: Time and Social Memory in Central Greece. History and Anthropology, Vol 23, No. 3, pp: 349-­‐374. • Knight, D. M. 2013. The Greek Economic Crisis as Trope. Focaal: Journal of Global and Historical Anthropology 65(Spring 2013): 147-­‐159. • Knight, D. M. 2013. Famine, suicide and photovoltaics: narratives from the Greek crisis. GreeSE: Hellenic Observatory papers on Greece and Southeast Europe (67): 1-­‐44. (Available Online). • Müller, B. 2007. Disenchantment with Market Economies: East Germans and Western capitalism. Oxford: Berghahn. • Önis, Z. and B. Rubin. 2003. The Turkish Economy in Crisis. London: Routledge. LECTURE 5: RISE OF THE FAR-­‐RIGHT IN EUROPE There has been a recent re-­‐emergence of nationalism in many parts of Europe under different global and transnational conditions. The success of far-­‐right parties in the 2014 European elections and the prominence of openly neo-­‐Nazi groups in crisis-­‐stricken nations demonstrates how once marginalised political ideologies have become institutionalised. In southern Europe far-­‐right movements are appealing in the face of rising unemployment, financial inequality and disillusionment with neoliberal economics and mainstream politics. How and why has the European far-­‐right gained popularity and what are the consequences for the future of European politics? • Berezin, M. 2007. Revisiting the French National Front: The Ontology of a Political Mood. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, Volume 36, Number 2, pp: 129-­‐146. (Online: http://www.scribd.com/doc/223164850/Berezin-­‐FN-­‐2007) • Dalakoglou, D. 2013. Facing Neo-­‐Nazis in public: A Story about an Anti-­‐Fascist Motorbike Patrol. Online: http://www.crisis-­‐scape.net/blog/item/138-­‐anti-­‐fascist-­‐motorbike-­‐patrol. • Dalakoglou, D. 2013. Neo-­‐Nazism and neoliberalism: a few comments on violence in Athens at the time of crisis. Working USA, Volume 16, Number 2, pp: 283-­‐292. • Givens, T. E. 2005. Voting for the Radical Right in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. • Holmes, D. 2000. Integral Europe: Fast-­‐Capitalism, Multiculturalism, Neofascism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. • Kirtsoglou, E., Theodossopoulos, D. and D. M. Knight. 2013. ‘Anthropology and the Crisis in Greece’: Forum on rise of Greek ‘Golden Dawn’ party. Suomen Antropologi: Journal of the Finnish Anthropological Society, Volume 38, Number 1, pp: 104-­‐115. • Orszag-­‐Land, T. 2009. Disappointed Eastern Europe Confronts Its Neo-­‐Nazis. Contemporary Review, Vol. 291, Issue 1694, pp: 280. (Online: http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Disappointed+Eastern+Europe+confronts+its+neo-­‐Nazis.-­‐

a0211029177) • Pinto, A. C. (ed.). 2010. Rethinking the Nature of Fascism: Comparative Perspectives. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. LECTURE 6: TIME AND POLYTEMPORALITY 21 When discussing culturally significant events within the context of western European history, there are episodes that may appear temporally distant or detached. However, some of these distant events may become culturally close at specific historical moments. In this lecture we will challenge previous conceptions of time as linear in relation to culture and nationalism. We will explore some diverse theories of time and critically assess the notions of polytemporality and cultural proximity. With specific cultural mediation, some past events are recalled as if they possess a contemporary quality – they are culturally proximate. As an embodiment of past events, cultural proximity can be facilitated by collective memory, objects and artefacts, nationalist rhetorics and the education system. • Fabian, J. 1983. Time and the Other: how anthropology makes its object. New York: Columbia University Press. • Knight, D. M. 2012. Cultural Proximity: Time and Social Memory in Central Greece. History and Anthropology, Vol 23, No. 3, pp: 349-­‐374. • Ricoeur, P. 1983. Time and Narrative: volume 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. • Serres, M. (with Latour, B.). 1995. Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. • Stewart, C. 2012. Dreaming and Historical Consciousness in Island Greece. Harvard: Harvard University Press. • Sutton, D. 2001. Remembrance of Repasts: an anthropology of food and memory. Oxford: Berg. • Sutton, D. 2011. Memory as a Sense: a gustemological approach. Food, Culture, Society, Volume 14, Issue 4, pp: 462-­‐475. FRIDAY FILM: TBC 22 TUTORIALS

TUTORIAL 1 How did Rivers approach ethnographic data? • W.H.R. Rivers. "The Primitive Conception of Death" in Richard Slobodin (ed.) W.H.R. Rivers: Pioneer Anthropologist, Psychiatrist of the Ghost Road TUTORIAL 2 How did Malinowski approach ethnographic data? • Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1916. ‘Baloma: The Spirits of the Dead in the Trobriand Islands’ Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 46:353-­‐430 (focus your reading on sections I, II, VI and VII) Compare Radcliffe-­‐Brown’s focus on the ‘social physiology’ or ‘system’ of Andamanese life versus Malinowski’s interest in the pragmatic or functional aspect of Trobriand language. • Radcliffe-­‐Brown, A. 1922. The Andaman Islanders. Chapter V, Pp. 229-­‐246. • Malinowski, B. 1935. Coral Gardens and Their Magic, Volume II, Pp. 4-­‐11. TUTORIAL 3 Norms and structures. This tutorial explores the development of the idea of structure in social anthropology between the 1930s and 1950s. Read the material by Metcalf, Wilson and Fortes looking at how social anthropologists built up a normative picture of social behaviour especially around kinship relationships. • Metcalf, P. 2005. Anthropology the Basics, chapter 3. • Wilson, M. 1951. ‘Witch-­‐beliefs and social structure’. American Journal of Sociology, 56. • Fortes, M. ‘Primitive Kinship’ in Spradley (ed) Conformity and Conflict. TUTORIAL 4 Process and development. The tutorial examines the adjustment and adaptation of social structuralism to the need to analyse contingent processes of social action, on the one hand, and large scale processes of development, on the other. In what ways did structural functionalism help/hinder our understanding of the social? • Firth, R. 1951. Elements of Social Organisation. Ch1: ‘The Meaning of Social Anthropology’. • Sahlins, M. ‘Poor Man, Rich Man, Big Man, Chief’. Comparative Studies in Society and History TUTORIAL 5 Reciprocity and gift exchange as a human universal. Levi-­‐Strauss (drawing on Mauss) argues for reciprocity as the fundamental human universal. What are we to make of the universal capacity to give and to receive – is exchange best understood cognitively, historically or in terms of social 23 structure (or all three?) • Graeber, D. (n.d.) ‘On the Moral Ground of Economic Relations: A Maussian Approach’. English version of a paper for special issue of La Revue du Mauss. K. Hart (ed.) (forthcoming). http://openanthcoop.net/press/2010/11/17/on-­‐the-­‐moral-­‐grounds-­‐of-­‐economic-­‐relations/ • Levi-­‐Strauss, C. 1969. The Elementary Structures of Kinship. ChV, ‘The Principle of Reciprocity’. • Metcalf, P. 2005. Anthropology, the basics. pp. 105-­‐114. TUTORIAL 6 Discussion of the role of ritual in M. Bloch’s analysis of Merina circumcision rites: see ‘From Cognition to Ideology’ in R. Fardon (ed.) Power and Knowledge (1985). Bloch’s perspective on ritual is different from the ones we have dealt with in the lectures. Compare and contrast the views you have learned about in lectures with what Bloch is arguing for here. See also, C. Bell, Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice, chp. 8. For those who are keen to know more about Bloch’s perspective see: • M. Bloch in 'The Past and the Present in the Present', Man 12 (1977). These two works by Bloch (1977 & 1985) are also available, in slightly different form, in Bloch Ritual, History and Power (1989). TUTORIAL 7 Discussion of the debate between the intellectualists and symbolists over the nature of religious thought. • R. Horton’s and J. Beattie’s chapters in B. Wilson’s edited book, Rationality (see above), to gain an appreciation of the intellectualist and symbolist positions respectively. TUTORIAL 8 This tutorial will focus on the contribution of feminist anthropology to the history of the discipline. In particular, attention will fall on the feminist critique of classic oppositions in anthropological writing: male and female, culture and nature, society and individual. Do all societies share these orienting dichotomies? If not, then what problems does this cause for anthropological modes of knowledge? • Strathern, Marilyn. 1980. ‘No Nature, No Culture: the Hagen Case’. In C. MacCormack & M. Strathern (eds.). Nature, Culture and Gender. Cambridge University Press. • Moore, Henrietta. 1988. Feminism and Anthropology. Polity [especially chps 1 & 2]. TUTORIAL 9 This tutorial will examine further the reflexive turn in anthropology in the late 1980s. What were the consequences of anthropologists becoming aware of the autonomy of language and the mediating role of text? What consequences did this have for ethnographic writing? • Clifford, James 1986. ‘On ethnographic allegory’, In Writing Culture. The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography Clifford & Marcus [eds]. University of California Press. 24 •

Geertz, Clifford. 1988. ‘Being There: anthropology and the scene of writing’, in Works and Lives: the Anthropologist as Author. Cambridge, Polity. TUTORIAL 10 Global Economic Crisis Are we witnessing a time of irreversible change in the capitalist economic system? If so, should anthropologists be suggesting alternative socio-­‐economic systems that ‘suit’ particular societies? How can anthropologists cut through the layers of rhetoric and media speculation which influence both their own views and those of their informants? Can anthropologists make use of these essentialised media perspectives for academic purposes? What ethical considerations are involved in studying the poverty and turmoil of others for academic gain? • Calabresi, M. and J. Kakissis. 2001. On the Precipice: Can Greece Save Itself — and the Dream of a United Europe? In Time Magazine, Monday, Nov. 21, 2011. • Hart, K. and H. Ortiz. 2008. Anthropology in the financial crisis. In Anthropology Today, Volume 24, Number 6, pp: 1-­‐3. 25 ESSAYS

Students must write TWO assessed essays for the module. The first essay question must be chosen from the list below under Essay 1 (DEADLINE: 23:59 FRIDAY 24th OCTOBER 2014) The second essay question must be chosen from the list below under Essay 2 (DEADLINE: 23:59 FRIDAY 21st NOVEMBER 2014). Essays should be submitted via MMS: https://www.st-­‐andrews.ac.uk/mms/ The word limit for each essay is between 1500-­‐2000 words. Please make full use of ethnographic examples. ESSAY 1 1. Why was the concept of totemism important in early anthropology? 2. Why was fieldwork so important for the development of modern anthropology? 3. Write a review of one of one the following works: We the Tikopia (Firth), Hunger and Work (Richards), Peasant Life in China (Fei), The Nuer (Evans Pritchard), Political Systems of Highland Burma (Leach), Tristes Tropiques (Levi-­‐Strauss). When was the book you have chosen published? How does it fit into the broader theoretical concerns of anthropology at that time? 4. Comparing two or more ethnographies written between 1930 and 1960 explore how ideas of ‘function’ and ‘structure’ changed during this period. 5. Classic ethnography was synchronic in approach. How did anthropologists deal with questions of time and change during the 1950s? ESSAY 2 6. What, if any thing, do rituals communicate? Compare and contrast the ideas on this subject of at least two anthropologists. See readings for week 5. 7. Outline the case for and against the view that religious thought and practice is rational. See readings for week 6. 8. How did debates in feminist anthropology influence the practice and writing of ethnograpy? (See page 18 for recommended readings) 9. What kinds of solutions to the crisis of representation do the Writing Culture debates highlight? (See page 18 for recommended readings) 26 HINTS ON WRITING ESSAYS

SA2001 is assessed as follows: Two assessed essays, each 1500 to 2000 words in length, to be submitted by FRIDAY 24th OCTOBER and FRIDAY 21st NOVEMBER. Each essay is worth 20% of the final mark. One two-­‐hour long examination. The exam is worth 60% of the final mark. Please note the following key points: Essays should be typed and submitted via MMS (https://www.st-­‐andrews.ac.uk/mms/) Essays should be properly referenced, especially direct quotations from books and articles, and a bibliography should be attached. The bibliography should only contain items that have been specifically referred to in the text. We strongly recommend that you follow the system explained in the last section of this handbook. Consult your lecturer/tutor/supervisor if in doubt. ESSAY WRITING 1. Writing an essay or report is an exercise in the handling of ideas. It is not the mere transcription of long and irrelevant passages from textbooks. To gain a pass mark, an essay or report must show evidence of hard thinking (ideally, original thinking) on the student's part. 2. When a lecturer sets you an essay or report he or she is explicitly or implicitly asking you a question. Above all else your aim should be to discern what that question is and to answer it. You should give it a cursory answer in the first paragraph (introduction), thus sketching your plan of attack. Then in the body of the essay or report you should give it a detailed answer, disposing in turn of all the points that it has raised. And at the end (conclusion) you should give it another answer, i.e. a summary of your detailed answer. Note If the question has more than one part you should dedicate equal attention to each one. 3. An essay or report must be based on a sound knowledge of the subject it deals with. This means that you must read. If you are tempted to answer any question off the top of your head, or entirely from your own personal experience or general knowledge, you are asking for trouble. 4. Make brief notes as you read, and record the page references. Don't waste time by copying out long quotations. Go for the ideas and arrange these on paper. Some people find that arranging ideas in diagrams and tables makes them easier to remember and use than verbal passages. You will find it easier to do this if you keep certain questions in mind: What is the author driving at? What is the argument? Does it apply only to a particular society, or are generalised propositions being made? How well do the examples used fit the argument? Where are the weaknesses? Also think about the wider implications of an argument. Copy the actual words only if they say something much more aptly than you could say yourself. It is a good plan to write notes on the content of your reading in blue and your own comments on them in red. There is another aspect of your reading which should go hand in hand with the assessment of any one item: you should compare what you have read in different books and articles. Test what one author proposed against evidence from other societies: what do the different approaches lend to one another? In this way you should begin to see the value (and the problems) of comparison and learn that writers disagree and write contradictory things, and that all printed matter is not indisputable just because it lies between hard covers. Note that as well as showing evidence of reading of set texts, good answers link the essay topic back to material given in lectures or tutorials. You can also gain marks by including additional reading, providing it is clear from your essay that you have actually read it! 27 5. Don't then sit down and write the essay or report. Plan it first. Give it a beginning, a middle, and an ending. Much of the information you will have collected will have to be rejected because it isn't relevant. Don't be tempted to include anything that hasn't a direct bearing on the problem expressed in the title of the essay or report. Note that in the introductory paragraph it is a good idea to make it absolutely clear to the reader exactly what you understand by certain crucial concepts you will be discussing in the essay -­‐these concepts will probably be those which appear in the essay title. Define these concepts if you think there may be any ambiguity about them. Note also that when you give examples to illustrate a point be careful not to lose track of the argument. Examples are intended to illustrate a general (usually more abstract) point; they are not a substitute for making this point. 6. When you finally start on the essay or report, please remember these points: (a) Leave wide margins and a space at the end for comments. Any work that is illegible, obviously too long or too short, or lacking margins and a space at the end will be returned for re-­‐writing. Essays should be typed, preferably on one side of the paper and double-­‐spaced. (b) Append a bibliography giving details of the material you have read and cited in the essay. Arrange it alphabetically by author and by dates of publication. Look at the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute as an example of the style of presenting a bibliography. N.B. In the body of the essay or report, whenever you have occasion to support a statement by reference to a book or article, give in brackets the name of the author and date. To acknowledge a quotation or a particular observation, the exact page number should be added. For example, 'Shortly after the publication of The Andaman Islanders, Radcliffe-­‐Brown drew attention to the importance of the mother's brother (Radcliffe-­‐Brown 1924). What kindled his interest in the South African material was the pseudo-­‐historical interpretation of Henri Junod (Radcliffe-­‐Brown 1952: 15) ...........' If you are not sure how to do this, look in the journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute or some monograph in the library to get an idea of how this is done. Alternatively, footnote your references. Note that if you simply copy a writer's words into your essay without acknowledgement you will lose marks, and could even receive a zero mark. 7. Footnotes should be placed either at the foot of each page, or all together at the end. If on each page, they should be numbered consecutively from the beginning of each chapter, e.g. 1-­‐22. If placed all together at the end, they should be numbered consecutively throughout the whole research project, e.g. 1-­‐103, in which case do not start renumbering for each chapter. 8. Footnote references in the text should be clearly designated by means of superior figures, placed after punctuation, e.g. ................the exhibition. 10 9. Underlining (or italics) should include titles of books and periodical publications, and technical terms or phrases not in the language of the essay, (e.g. urigubu, gimwali). 10. Italicize: ibid., idem., op.cit., loc.cit., and passim. 11. Single inverted commas should be placed at the beginning and end of quotations, with double inverted commas for quotes-­‐within-­‐quotes. 12. If quotations are longer than six typed lines they should be indented, in which case inverted commas are not needed. 13. PLEASE TRY TO AVOID GENDER-­‐SPECIFIC LANGUAGE. Don't write he/him when you could be referring to a woman! You can avoid this problem by using plurals (they/them). Referencing: Correct referencing is a critical aspect of all essays. It is the primary skill that you are expected to learn 28 and it also guards you against the dangers of plagiarism. Make sure that when you are reading texts that you note down accurately the source of information by recording the name of the author, the book title, page number and so forth. This will enable you to reference correctly when it comes to writing your essay. Adequate referencing requires you to indicate in the appropriate places in body of your essay the source of any information you may use. Such references vary in kind, but a general guide to the correct format would be: A general reference: … as Turnbull’s (1983) work demonstrates … … the romanticisation of Pygmies has been commonplace in anthropology (e.g. Turnbull 1983) … Note: In this example, the author is referring to Turnbull’s work in a general way. If the author was referring to specific ideas or details made by Turnbull, then the page number needs to be specified. A paraphrase: … Turnbull describes how the Ituri Forest had remained relatively untouched by colonialism (Turnbull 198 3: 24) … Note: This is more specific than a general reference as it refers to a particular point or passage by an author. It is your summary of a point made by someone else (in this case Turnbull). When paraphrasing, you must always include the page number in your reference. A quotation: … under these circumstances, “the Mbuti could always escape to the forest” (Turnbull 1983: 85). Note: All quotes from anyone else’s work must be acknowledged and be placed within speech marks. The page number or numbers must be referenced. If you need to alter any of the words within the quote to clarify your meaning, the words changed or added should be placed in square brackets [thus] to indicate that they are not those of the original author. Bibliography: All tests referenced within the body of your essay must be included within the bibliography. Entries in the bibliography should be organised in alphabetical order and should contain full publication details. Consult an anthropological journal, such as the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (JRAI), to see how the correct format should appear. This is available both electronically and in hard copy. The standard format of bibliographic referencing is as follows: Book: Turnbull, C.M. 1983. The Mbuti Pygmies: Change and Adaptation. New York, Holt Reinhart and Wilson. Edited Collection: Leacock, E. & R. Lee (eds) 1982. Politics and History in Band Societies. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press. Chapter in edited collection: Woodburn. J.C. (1980). Hunters and gatherers today and reconstruction of the past. In Soviet and western anthropology (ed.) E. Gellner. London: Duckworth. Journal article: Ballard, C. 2006. Strange alliance: Pygmies in the colonial imaginary. World Archaeology,38, 1, 133 151. Web pages: It is unadvisable to use web sites unless directed to them by a lecturer. There is a great deal of rubbish on the Internet. However, if you do, it is important that you provide full details of the web-­‐page address as well as the date on which the page was accessed. Miller, J.J. 2000, Accessed 22/09/2006. The Fierce People: The wages of anthropological incorrectness. Article available electronically at: http://www.nationalreview.com/20nov00/miller112000.shtml. 29 If you are not sure how to do this, look in the journal JRAI or some monograph in the library to get an idea of how this is done. Alternatively, footnote your references. Note that if you simply copy a writer's words into your essay without acknowledgement you run the risk of plagiarism and will lose marks, and may even receive a zero mark. 8. Please also note the following: (a) Spellings, grammar, writing style. Failure to attend to these creates a poor impression. Note, especially: society, argument, bureaucracy. (b) Foreign words: Underline (or italicize) these, unless they have passed into regular English. (c) PLEASE TRY TO AVOID GENDER-­‐SPECIFIC LANGUAGE. Don't write he/him when you could be referring to a woman! You can avoid this problem by using plurals (they/them). 30