Evolution Connection Unit 4 - AHS

Evolution Connection #4: Cladistics and Evolution by Natural Selection

In this unit we discussed the role of DNA in cells. We have talked a good deal about how proteins are made, and their many functions within an organism. Our next evolution connection will look at the theory of evolution by natural selection; we will learn how species can change over time, and how new species can come to be. As you go

through this evolution connection, keep in mind that mutations in DNA and their resulting changes in protein structure are responsible for all the variation we see in the organisms of Earth!

Anthro.palomar.edu

Part I: Evidence for Evolution

Look for the following sections, each of which examines a different type of evidence for evolution:

•

Structural Homologies

•

Fossil Evidence

•

Observational Evidence (we can observe changing populations)

•

Molecular Evidence

Go to http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/evo_01

Start with “Patterns”. Explore the following pages in this module:

à Homologies and Analogies.

1.

What are homologies? What are analogies? Which one comes from a common ancestor?

2.

Bird and bat wings are analogous. Why did similar structures evolve separately in these two groups?

1

Video: “Who Was Charles Darwin?”

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/educators/teachstuds/svideos.html

3.

What characteristics made Darwin especially well suited for science?

4.

What did Darwin see and do on his 5-‐year voyage aboard the Beagle ?

5.

What new idea did Charles Darwin introduce to science? How did it challenge the current understanding of biodiversity?

Fossil Evidence

Video: “How Do We Know Evolution Happens?” http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/educators/teachstuds/svideos.html

6.

How do fossils give us a picture of change over time?

7.

What distinguishing feature of the fossil Pakicetus skull identified it as related to a whale? Why was this surprising?

8.

Why do scientists seek fossils that are intermediate in form and time between modern forms and their probable earliest ancestors?

Interactive: Transitional Fossils

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/evolution/fossil-‐evidence.html

9.

This resource describes 5 important transitional fossils that have helped our understanding of evolutionary

Fossils history. Fill in the table below with information about each one.

Represents a link between what two modern groups?

What physical structure(s) were modified from earlier ancestors?

Tiktaalik rosae

How long ago?

Thrinaxodon

Archaeopteryx

Ambulocetus natans

Australopithecus afarensis

2

We Can Observe Changing Populations

Video: How Does Evolution Really Work? http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/educators/teachstuds/svideos.html

10.

What are the four components of natural selection?

A.

B.

C.

D.

11.

What determines an individual hummingbird’s beak length?

12.

What factors in the environment might select for beak length and shape within hummingbird populations?

13.

How can hummingbird DNA help Dr. Schneider determine the evolutionary history of hummingbirds?

In-‐class activity: The Grant

Finch Study Data

Molecular Evidence

Interactive: Darwin’s Predictions http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/evolution/darwins-‐predictions.html

Many scientific discoveries have supported Charles Darwin’s original theory of evolution by natural selection. This interactive examines 12 predictions Darwin made, and discusses supporting discoveries that have been made since

Darwin’s publication of his book.

14.

For each prediction, briefly describe the supporting evidence.

Evolution happens

Evolution happens through natural selection

Evolution by natural selection must have a mechanism

The mechanism is natural, not supernatural.

3

Embryology is "the strongest single class of facts in favor of change of forms."

Sexual selection also drives evolution.

All animals, including humans, descend from a common ancestor.

Humans evolved from an ape-‐like ancestor.

Modern humans arose in Africa.

The Earth is at least several hundred million years old.

Gaps in the fossil record will be filled in with key transitional fossils.

An insect with a

foot-‐long tongue must exist to pollinate this orchid.

Part III: Mechanisms of Evolution

In-‐class activity: Birds, beaks,

and natural selection.

Go to http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/evo_01

Click on “Mechanisms”. You will progress through all pages of this module.

15.

Briefly describe each of the following mechanisms of evolution:

A. Mutation:

B. Migration:

C. Genetic Drift:

D. Natural Selection:

16.

What are the three sources of genetic variation in sexually reproducing populations?

4

17.

List three examples of behaviors that have evolved by natural selection.

18.

Why do organisms do things that don’t necessarily increase their chance for survival: peacocks grow giant tails, penguins care for their young, and lobsters produce thousands of offspring.

19.

Define sexual selection.

20.

How does artificial selection support Darwin’s theory?

21.

List three examples of adaptations that have arisen by natural selection.

22.

What are vestigial structures? Give an example of a vestigial structure.

Flashy Fish

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/educators/lessons/lesson4/act2.html

23.

Fill in the chart below.

Pros Cons

Drab colors

Flashy colors

24.

In which pool does each survive best? Why?

25.

Why does it make sense for females to choose the brightest males? (Hint: after running your simulation you will be looking at the results page. Click on “read summary” under the results window.)

5

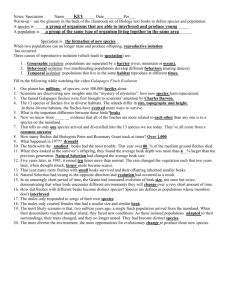

In-‐Class Activity 1: Grant Finch Study Data

Natural Selection in Real Time

"When we made the comparison between the size of the offspring generation and the population before selection, we found a measured, evolutionary response had taken place and it was almost identical to what we had predicted." -‐

Peter Grant

Darwin thought that evolution took place over hundreds or thousands of years and was impossible to witness in a human lifetime. Peter and Rosemary Grant have seen evolution happen over the course of just two years.

The Grants study the evolution of Darwin's finches on the Galapagos Islands. The birds have been named for

Darwin, in part, because he later theorized that the 13 distinct species were all descendants of a common ancestor.

Each species eats a different type of food and has unique characteristics developed through evolution. For example, the cactus finch has a long beak that reaches into blossoms, the ground finch has a short beak adapted for eating seeds buried under the soil, and the tree finch has a parrot-‐shaped beak suited for stripping bark to find insects.

The Grants have focused their research on the medium ground finch, Geospiza fortis, on the small island of Daphne

Major. Daphne Major serves as an ideal site for research because the finches have few predators or competitors.

(The only other finch on the island is the cactus finch.) The major factor influencing survival of the medium ground finch is the weather, and thus the availability of food. The medium ground finch has a stubby beak and eats mostly seeds. Medium ground finches are variable in size and shape, which makes them a good subject for a study of evolution.

The first event that the Grants saw affect the food supply was a drought that occurred in 1977. For 551 days the islands received no rain. Plants withered and finches grew hungry. The tiny seeds the medium ground finches were accustomed to eating grew scarce. Medium ground finches with larger beaks could take advantage of alternate food sources because they could crack open larger seeds. The smaller-‐beaked birds couldn't do this, so they died of starvation.

In 1978 the Grants returned to Daphne Major to document the effect of the drought on the next generation of medium ground finches. They measured the offspring and compared their beak size to that of the previous (pre-‐ drought) generations. They found the offsprings' beaks to be 3 to 4% larger than their grandparents'. The Grants had documented natural selection in action.

While beak size is clearly related to feeding strategies, it is also related to reproduction. Female finches tend to mate with males that have the same size beaks. These factors together can add to the development of new species.

The Grants return each year to Daphne Major to observe and measure finches. They have been collecting data on the finches for over 25 years and have witnessed natural selection operating in different ways under different circumstances.

6

Grants’ Finch Study Data

Figure 1 1976 All Daphne Birds

N = 751

1978 Survivors

N = 90

Beak Depth (mm)

Figure 1: Histogram of distribution of beak depth of medium ground finches ( Geospiza fortis ) on

Daphne Major, before and after the drought of 1977 (Grant 1986). Reprinted by permission of

Princeton University Press.

Figure 2

Midparent Bill Depth (mm)

°

=1976 population and

•

=1978 population

Figure 2: Relationship between beak depth of offspring and their parents in the medium ground finch ( Geospiza fortis ) population on Daphne Major. The slope of the relationship is the heritability

(Boag 1983).

1

©2001 WGBH Educational Foundation and Clear Blue Sky Productions, Inc. All rights reserved.

7

Figure 3 A

Estimates ± 95%

Confidence Limits

B

Daphne. All Edible Species x ± s.e.

Figure 3: Changes in Geospiza fortis population and seed abundance on Daphne major, before and after the drought of 1977 (Grant 1986).

2

©2001 WGBH Educational Foundation and Clear Blue Sky Productions, Inc. All rights reserved.

8

In-‐class Activity 2: Modeling Natural Selection

Birds, Beaks, and Natural Selection—A Simulation

In this simulation, students gather data to see how beak mutations can influence natural selection.

Objective

Students learn about the role of mutations in natural selection and evolution.

Procedures

1.

The three to four students in your group represent individual wading birds within a population of 100 birds. This population of wading birds has a wild-type beak that will be made of tongue depressors.

2.

Look at the wild-type beak model and construct a similar beak by wedging the screw

2 cm from the tips of the tongue depressors and using the rubber band to wrap the ends of the tongue depressors, making the beak like tongs.

3.

You will simulate the wading birds feeding.

• Add to your aquarium four of each type of food for each person in your group.

• Take turns feeding for 15 seconds to see how many of each type of food you get, using the feeding rules.

–Pick up only one piece of food at a time.

–Don't use the edge of the aquarium to hold food.

–Don't put your hand below water.

• Replace food before the next feeding trial.

–Wipe up any water on floor between trials.

• Each member of the group should do three trials of feeding; after each trial, record the results in the “Bird Beak Data Sheet.”

4.

Calculate and compare the average number of food pieces and types of food captured by your team members.

1

© 2001 WGBH Educational Foundation and Clear Blue Sky Productions, Inc. All rights reserved.

Adapted with permission from “Genetics and the Evolution of Bird Beaks” by Bonnie Chen.

9

5.

Now assume that three to four birds (your team members) in your population will undergo mutations in the genes that code for beak length. Each student will pick a mutation handout that will explain the kind of mutation and how it will affect the beak size of your offspring.

6.

Follow the instructions on your mutation sheet. If you received a beak mutation that requires a change, you will need to create the new beak for your offspring. For long beak mutations, use the extra-long glued tongue depressors, a screw, and the rubber band to make the beak tong-like. For short beak mutations, cut the wild-type beaks exactly in half using the scissors. Some mutations do not affect your offspring's beak; you will use the same wild-type beak. Answer these questions with your group:

• What was the significance of having only four individuals within a population of 100 wading birds have a mutation?

• Why did some mutations lead to a change in beak length and some not?

7.

You will now feed as your offspring, Generation 1. Because this time all members of a group will feed at once , two teams will work together during the feeding of the offspring. While one group feeds, the other group will time and monitor the feeding.

Then teams will switch roles. There will be three feeding trials of 15 seconds each, following the feeding rules, and food will be replaced between trials. Record your feeding data on the “Bird Beak Data Sheet” after each trial.

8.

Determine the survival rate of your offspring by following the directions below and record results in the “Bird Beak Data Sheet” in the Generation Results column.

Guidelines for determining offspring survival:

• If offspring consumed less than half of the parent's average number/amount of food minus 2, they will die. For example, if offspring consumed 4 pieces of food and parent's average number/amount of food was 14, then they will die. (4 is less than 5x14-2=5)

• If offspring consumed between half parent's average minus 2 to half of the parent's average, they will survive and reproduce 1 offspring.

• If offspring consumed more than half the parent's average, they will survive and reproduce 4 offspring.

9.

Compare your data and discuss the following questions in your group and record responses below.

• What happened when the offspring with changed beaks and the offspring with wild-type beaks fed together?

• For each type of beak, which food types were consumed? Which types were consumed the most?

2

© 2001 WGBH Educational Foundation and Clear Blue Sky Productions, Inc. All rights reserved.

10

• Based on the number of food items consumed, which birds survived? Which birds survived and produced the most offspring?

• Why might some surviving birds produce different numbers of offspring?

• What other factors besides beak length affected feeding in your population?

• What would you expect to happen to the population if the second generation were allowed to feed and reproduce under the same conditions?

• How did this simulation demonstrate natural selection?

• What is the role of mutations in natural selection?

• What is the role of sexual reproduction in natural selection?

• Which does natural selection act upon: the genotype or phenotype of traits?

• Explain the significance of the following statement: Natural selection operates on individuals, but evolution occurs at the level of the population.

• How is this simulation like the real world and how is it different in relation to feeding, mutations, beak lengths, and reproduction?

3

© 2001 WGBH Educational Foundation and Clear Blue Sky Productions, Inc. All rights reserved.

11

12

Mutation Handout: Birds, Beaks, and Natural Selection Activity

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No change in beak length:

Mutation does not change beak length. Protein codes for a beak length the same size as the wild-type beak.

Same as parent generation: two tongue depressors connected together (15 cm)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Long beak:

Mutation changes beak length. Protein codes for a beak longer than the wild-type beak.

Construct the long beak by using the long tongue depressors made of two tongue depressors glued together. Use a screw and rubber bands to secure the top of the beak like tongs. Wrap the rubber bands very tightly. Make sure that the beak will fully close!

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Short beak:

Mutation changes beak length. Protein codes for a beak shorter than the wild-type beak.

Mark the halfway point of the tongue depressors in the wild-type beak. (7.5 cm) Using scissors, cut the wild-type beak in half along the 7.5 cm line.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No change in beak length:

Mutation does not change beak length. Protein codes for a beak length the same size as the wild-type beak.

Same as parent generation: two tongue depressors connected together (15 cm)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

© 2001 WGBH Educational Foundation and Clear Blue Sky Productions, Inc. All rights reserved.

13