Migrating from Proprietary to Open Source Learning

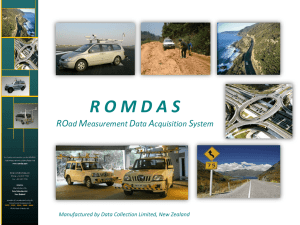

advertisement