The Basics of Monopolies

advertisement

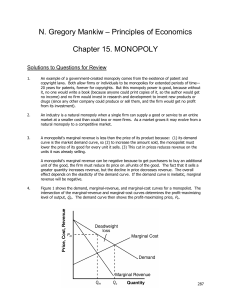

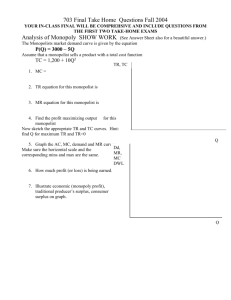

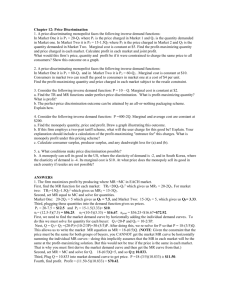

The Basics of Monopolies1 1 Layout of Monopolies Monopolistic markets differ from perfectly competitive markets in some very important ways. In the perfectly competitive market case, there are so many firms selling basically the same product that the production choices of an individual firm have no real impact on the price level, and firms have to take prices as given. For monopolies, the firm can impact the price depending on their quantity produced, and thus can set their own price by deciding said quantity. The perfectly competitive firm doesn’t see the market demand curve — remember, in a perfectly competitive market, the individual firm demand curve is just a horizontal line at the market price.2 The monopolistic firm, on the other hand, does see the market demand curve as its own demand curve. This means that, unlike in perfect competition, the more the monopolistic firm produces, the lower the price it can charge for each unit sold. As a result, we have two important results in a monopoly market: 1. The demand curve the a monopolist faces is downward sloping. 2. The marginal revenue (change in revenue caused by selling one additional unit) is decreasing as quantity increases (this is what causes our downward sloping marginal revenue curve).3 Note that, beyond a production of 1 unit, marginal revenue (M R) is always lower than price. This means the marginal revenue curve lies below the demand curve. Since each unit the 1 Disclaimer : This handout has not been reviewed by the professor. In the case of any discrepancy between this handout and lecture material, the lecture material should be considered the correct source. Despite all efforts, typos may find their way in - please read with a wary eye. 2 Why is it horizontal? Because no matter how many units the perfectly competitive firm sells, it will always face the same price per unit. 3 If the demand curve has a constant slope, the marginal revenue curve will have a slope exactly 1/2 that of the demand curve. Prepared by Nick Sanders, UC Davis Graduate Department of Economics 2009 monopolist sells means a lower price for every unit it sells, marginal revenue can actually become negative, as is shown in Figure 1.4 2 Profit Maximization in a Monopoly In a competitive market, profit maximization occurs when P = M C, and long-run profits are zero. For a monopolist, profit maximizing occurs when M R = M C, where M R is not necessarily equal to P . There is some basic economic logic here, and it isjust about the same as the perfect competition logic. If the revenue gains from selling one more unit are greater than the costs of producing that next unit, they you should produce that unit. Determining the profit maximizing price in a monopoly is relatively simple. First, find the point where M C = M R. Draw a vertical line through that intersection. Where the vertical line intersects the horizontal axis will tell you your profit maximizing quantity. Where the vertical line intersects the demand curve will tell you the profit maximizing price. To find profits, we need the ATC curve we learned about earlier in the discussion of perfect MC P PM D QM MR Q Figure 1: Monopolist marginal cost, marginal revenue, and demand curves. competition. Throwing that in gives us Figure 2. Just like in perfect competition, profits are 4 This happens whenever price elasticity of demand is less than 1, though we didn’t really discuss this in class. 2 MC PM ATC P Monopoly profits D QM MR Q Figure 2: Profits in a monopoly. calculated by calculating the difference between average total costs and price. Total profit is the area of the shaded square above. 3 Monopolies and Deadweight Loss One of the drawbacks to monopolies is that they create deadweight social loss. Graphically, the deadweight loss is shown in Figure 3. The deadweight loss results from the differences between monopoly pricing and competitive pricing, as well as monopoly output and competitive output. Intuitively, the logic is as follows: 1. Consumers are losing out on some consumer surplus (CS). Under perfect competition, P = M C. Under a monopoly, P > M C. CS goes down because of two factors. (a) There are some people that would have gotten the product (and some CS) under perfect competition that are no longer getting it (triangle B). (b) Those that are still getting the product have to pay more for it than they would under perfect competition, so the difference between marginal benefit and price has decreased (rectangle A). Note that rectangle A is not deadweight social loss (explanation below). 3 2. Surplus loss also occurs due to producers not selling as many units as they would under perfect competition (triangle C). Rectangle A is not considered deadweight loss, even though it is no longer consumer surplus. This is because it is now going to firms in the form of profits. So even though it isnt CS anymore, it hasn’t “vanished” like the deadweight loss area, it has just changed into producer surplus. Since the monopoly outcome is not the (efficient) perfectly competitive MC PM A B PC P C D QM QM MR Q Figure 3: Changes in surplus in a monopoly. outcome, we know there has to be some deadweight loss.5 5 Similar to the situation with taxation, how much of a difference there will be is related to the elasticity of the demand curve. 4