Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part

advertisement

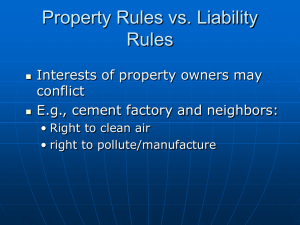

Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 Discussion Paper December 2005 1 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 © State of Victoria, Department of Justice 2005 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1986. Disclaimer: This publication is circulated for the purposes of generating comments on a proposal to review certain aspects of Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958. The State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that this publication is wholly without error. This publication is circulated on the understanding that the State of Victoria and its employees are not responsible for any action taken or any failure to take action on the basis of the material contained in this publication. This publication should not be viewed as constituting legal advice nor should it be relied on for the purposes of obtaining or providing legal advice in relation to any matter. 2 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Background 4 B. Principle of Proportionate Liability and Operation of Part IVAA 6 C. Potential Implications for the Voluntary Allocation of Risk under Contract 8 D. Options for Amending Part IVAA to Allow Voluntary Allocation of Risk under Contract 12 E. Retrospective Effect of Part IVAA 16 3 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 A. Background History of Proportionate Liability as Part of the Tort Law Reforms 1. Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 (‘the Act’), as introduced by the Wrongs and Limitation of Actions Act (Insurance Reform) Act 2003, came into effect on 1 January 2004. 2. The implementation of Part IVAA was part of a broader package of insurance driven reforms designed to respond to the contraction in the insurance market in 2001-2002. This was the result of a number of factors, including the collapse of HIH Insurance (which held 35% of the insurance market1); a general reduction in competition between insurance providers; and the withdrawal of certain insurance services as a result of substantial awards of damages being made by courts (particularly in NSW) in relation to professional indemnity and public liability litigation. 3. Commonwealth, State and Territory governments received submissions from the insurance industry and various professional associations strongly recommending that the current liability system be altered to assist in correcting severe market failure in the provision of professional indemnity insurance (‘PII’). In response to concerns over the withdrawal of PII by various insurance providers, the Standing Committee of Attorneys-General and the Ministerial Council for Corporations convened a joint working party to review and address options for introducing proportionate liability (“PL”) reforms and professional standards legislation. 4. Although jurisdictions sought to achieve reforms that were consistent, agreement could not be reached to achieve uniformity in relation to PL provisions as certain jurisdictions had already introduced various forms of proportionate liability.2 Recent Review of Proportionate Liability 5. The Victorian Government is continuing to monitor the effects of the tort law reforms and to take account of concerns raised or identified in relation to the operation of the new provisions of the Act. 6. In monitoring these reforms one concern that has been raised with the Victorian Government is the potential impact of the PL provisions in Part IVAA on existing and future contractual arrangements to allocate risk. 1 Moodie, Grant, ‘Proportionate liability: damages for misleading or deceptive conduct’, CCH Australia (15 September 2004) 2 At the time of the joint meeting of SCAG and MINCO in April 2003, during which the proposals for PL and professional standards legislation were being finalised, NSW had already enacted PL provisions in Part 4 of its Civil Liability Amendment (Personal Responsibility) Act 2002, Western Australia had introduced a Civil Liability Amendment Bill 2003 similar to the NSW Act and Queensland had introduced a Civil Liability Bill 2003 which differed in parts from the NSW and WA Acts. 4 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 7. While at the time of publication of this paper, the PL provisions have not been subject to determination by the Victorian Supreme Court, there is a strong view that a significant degree of uncertainty surrounds the practical operation of the PL provisions, which in turn creates uncertainty when establishing contractual arrangements as part of the usual course of business. 8. In particular, it is not known how PL will affect risk allocation arrangements for major commercial transactions in Victoria; and whether PL can be used by contracting parties to avoid their contractually assumed liability. The key concerns that arise presently for businesses in the absence of judicial consideration are: • the potentially significant financial consequences that may flow from an adverse judicial ruling on the ability of parties to allocate risk pursuant to contract; and • the prolonged uncertainty for contractual position for risk allocation both in existing and future commercial arrangements until the Victorian Supreme Court provides a definitive interpretation of Part IVAA. 9. This position in turn has the potential to significantly increase the current risk management costs of a project particularly associated with insurance, performance bonds and contractual indemnities or guarantees from third parties. 10. As such, the Victorian Government considers that a targeted review is necessary so as to ensure that the current law on PL is transparent, fair and will clarify any legislative uncertainty which may have been created by the implementation of the PL reforms in 2004, regarding the contractual allocation of risk. 5 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 B. Principle of Proportionate Liability and the Operation of Part IVAA 11. Part IVAA implements a system of PL for claims for economic loss or damage to property in an action for damages (whether in tort, in contract, under statute or otherwise) arising from a failure to take reasonable care. Part IVAA also applies to a claim for damages for a contravention of section 9 (‘misleading and deceptive conduct’) of the Fair Trading Act 1999 (Vic) - see section 24AF(1) of the Act. A copy of Part IVAA is in Attachment 1. 12. Previously, under the general law principle of ‘solidary’ or joint and several liability, plaintiffs were able to retrieve 100% of their loss from a defendant that may have only caused only 1% of that loss, while the party who contributed to 99% of the loss may not have been sued by the plaintiff (for reasons such as lack of capacity to meet the plaintiff’s loss). The burden then fell on the named defendant(s) to identify and join other defendants to the proceedings. 13. Under the system of PL, as implemented by Part IVAA, liability for any economic loss is to be apportioned according to the responsibility of each ‘concurrent wrongdoer’ (i.e. where there is more than one person who has independently or jointly caused the plaintiff’s loss – see section 24AH of the Act). In other words, in any proceeding, a court must not give judgment against a defendant for more than an amount that reflects the proportion of loss or damage the court considers ‘just’ having regard to that defendant’s responsibility (see section 24AI(1) of the Act). 14. The legislation was designed to ensure that Courts recognise that some parties should not bear the responsibility of others merely because they have the capacity to pay compensation. Instead, it reflects the fundamental moral maxim that wrongful conduct should incur a sanction that is proportionate to the culpability of that conduct (‘the proportionality principle’); which arguably was previously infringed by the principle of joint and several liability.3 15. However, the Victorian legislation does not implement PL in the same manner it is implemented in some other jurisdictions. Section 24AI(3) of the Act states that in apportioning responsibility between defendants in the proceeding, the court must not have regard to the comparative responsibility of any person who is not a party to the proceeding (unless that non-party wrongdoer is either dead, or if a corporation, has been wound up)4. In other words, in apportioning responsibility between named defendants to a proceeding, a court cannot, in determining the 3 See Goudkamp, James, ‘The Spurious Relationship Between Moral Blameworthiness and Liability for Negligence’, MULR [2004] 11 4 For example some other jurisdictions either direct or provide a discretion for a court to consider the comparative responsibility of a concurrent wrongdoer who is not a party to the proceeding section 87CD Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth); section 35(3), Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW); section 107F(2), Civil Law (Wrongs) Act 2002 (ACT); section 31(3), Civil Liability Act 2003 (QLD); section 8(2), Law Reform (Contributory Negligence and Apportionment of Liability) Act 2001 (SA); section 13(2), Proportionate Liability Act 2005 (NT); section 5AK(3), Civil Liability Act 2002 (WA). However, in certain jurisdictions the balance in favour of the defendant is offset, to a certain degree, by provisions that allow a court to order a defendant to pay the plaintiff’s costs on an indemnity basis. This occurs where the plaintiff unnecessarily incurs costs due to the defendant’s failure to inform the plaintiff of another concurrent wrongdoer – see for example s5AKA, Civil Liability Act 2002 (WA). 6 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 facts, have regard to any other non-party wrongdoer’s possible contribution (unless that non-party is either dead or an insolvent company). Accordingly, a named defendant must join any other wrongdoer who may be responsible for the plaintiff’s loss or, effectively, that defendant will not be able to rely on any evidence or argument seeking to apportion liability to a non-party. 16. The potential effect of section 24AI(3) is that named defendants are faced with the possibility that a court could apportion up to 100% of liability between the named defendants in circumstances where, had the court considered the comparative responsibility of any non-party concurrent wrongdoers, the liability apportioned between the named defendants would be less. The named defendants bear the risk of a court apportioning any responsibility of a non-party concurrent wrongdoer to the defendants, unless the concurrent wrongdoers are either joined to the proceedings, or are dead, or are companies that have been wound up. Whether this risk will materialise will depend on the facts, the evidence adduced in the absence of any non-party concurrent wrongdoers and the way the case is put to a court. 17. From a policy perspective, section 24AI(3) was implemented to reflect a fairer balance in the PL system between plaintiffs and defendants in Victoria. Generally, defendants are better placed than plaintiffs to identify relevant wrongdoers who may have contributed to a plaintiff’s loss. For example, in a large commercial transaction involving a number of parties (and potential wrongdoers) the plaintiff may have a contractual relationship with only one of those parties and may not be in a position to identify all parties who may have a role in that transaction. Further, and more generally, placing the burden of identifying all parties on the defendant will ensure that potential defendants to do not collude to avoid being identified by a plaintiff. 18. While the PL provisions have been implemented in response to the insurance crisis and as part of the tort law reforms, they take much of their content from the Davis Inquiry6 of the early 1990s. The Davis Inquiry recommended a move from a system of ‘solidary’ liability towards a system of PL on the basis that solidary liability created an injustice for institutional or ‘deep-pocket’ defendants. The draft PL legislation annexed to the Report of Stage Two allowed express contracting out of the legislation’s effects. ‘Contracting out’ has been provided for in both the New South Wales and Western Australian legislation (discussed further in Part D of this paper). 19. It should be noted that PL does not apply to claims arising under various statutory compensation schemes (as set out in section 24AG of the Act), such as the Transport Accident Act 1986 (Vic) and the Workers Compensation Act 1958 (Vic); nor does it apply to personal injury claims. 6 Davis, Jim, Inquiry Into the Law of Joint and Several Liability: Report of Stage One and Report of Stage Two (Commonwealth of Australia, 1994, 1995) 7 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 C. Potential Implications for the Voluntary Allocation of Risk under Contract 20. A fundamental characteristic of contract and the risk allocation philosophy which underpins it is that all project risk should be distributed in accordance with the terms of the contract between the parties. It also reflects the generally recognised position that the law of contract is a ‘higher’ law than of torts and that parties ought to be able to vary or exclude rights or liabilities unless otherwise prohibited by law or on public policy grounds.7 21. However, under section 24AI(1) of the Act there is the potential for courts to construe the relevant provisions in such a way so as to override the contractual allocation of risk between parties to a contract and instead simply determine ‘responsibility’ in the narrow sense of what actions or omissions were attributable to each party that contributed in fact to the plaintiff’s loss. 22. Two simple examples can be used to illustrate the potential problems Part IVAA may pose for parties seeking certainty when entering into commercial arrangements. In the first scenario Party (P) enters into a contract with Party D1 to build a new building. The contract between P and D1 states that D1 will fully indemnify P (assume 100% liability for any loss incurred by P) in consequence of that transaction. D1 then sub-contracts with D2 to undertake various aspects of the construction of that building. Subsequently, the building collapses and on a factual enquiry, D2’s negligence is held to be 80% responsible for P’s loss. Under solidary liability, P would only need to sue D1 to attempt to recover 100% of the loss. Currently, under Part IVAA, should P sue D1, and D1 were to join D2 to the proceedings, P risks only recovering 20% of P’s loss from D1 - despite the contractual indemnity which provides that D1 will assume 100% of P’s loss. See Attachment 2. 23. In the second scenario, P enters into a contract with D1 to build a new building. D1 enters into a contract with D2 that might stipulate that in undertaking to construct the building for D1, D2 has agreed to fully indemnify D1. D2 then sub-contracts with D3 to supply the materials for the construction of that building. Together, D1, D2 and D3 negligently cause P’s economic losses. Under Part IVAA, P elects to sue D1 and D1 joins D2 and D3 to the proceeding. There is a risk, however, that on a factual enquiry the court could find D1 50% responsible for P’s loss, and therefore hold D1 50% liable for P’s damages – despite D1’s contract with D2 which provides that D2 will indemnify D1 for 100% of any loss arising out of the project. See Attachment 3. 24. Currently, s24AJ of the Act stipulates that once judgment has been given against a defendant in relation to an apportionable claim, that defendant cannot be required to contribute to the ‘damages’ recovered or recoverable from another concurrent wrongdoer in the same proceeding or cannot be required to indemnify any such wrongdoer. 25. This is because the definition of ‘damages’ under s24AE of Part IVAA includes ‘any form of monetary compensation’ and that phrase arguably is sufficiently broad 7 Star L and Paine T, ‘Principles of Liability’, Australian Torts Reporter: Vol 2, (CCH Australia Ltd, 1998) 8 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 enough to include any contractual entitlement to indemnity, where the entitlement ‘arises out of’ a failure to take reasonable care, as stipulated in s24AF(1)(a). 26. As a result, section 24AJ prevents a defendant from enforcing any contractual indemnification provisions it has agreed to with another ‘concurrent wrongdoer’. Accordingly, it is open to a concurrent wrongdoer to invoke this section to limit its liability under the indemnity contract to ‘that proportion of the loss or damage claimed that the court considers just having regard to the extent of [its] liability for the loss or damage’. 27. This means that in Scenario 2 (see Attachment 3) if D2 and D3 were respectively found 30% and 20% liable (against D1’s 50% liability) then under section 24AJ, D1 could not enforce its contract with D2 to indemnify it for that 50%. As a result, D2 has managed to reduce its contractual liability to D1 from 100 % to 0%, despite contractually assuming 100% of D1’s liability. 28. From the above discussion it also follows that a party that has assumed contractual liability for the actions of others might wish to be named as a defendant and to lead evidence that it was negligent in some minor way, so as to invoke the operation of Part IVAA and therefore to reduce the amount for which it would have otherwise been held liable. For example, a party could become nominally involved in the transaction such that if some deficiency did ensue, it would stand a chance of being named as a defendant and being held liable for, as an example, only 5% of the loss. 29. Conversely, there is a possibility that a plaintiff or a co-defendant in seeking to impute as much responsibility to a particular party may seek to adduce evidence that the defendant has not failed to exercise reasonable care (such that the PL provisions are not invoked) and therefore that particular defendant’s strict liability under contract can be enforced. Again, in the absence of judicial consideration, these are examples of potential situations that could arise from the operation of the current provisions. 30. Section 24AJ does not, however, prevent a defendant from enforcing any indemnity arrangements it may have with other parties such as insurers, guarantors or performance bond issuers who are not actually involved in the relevant project in any practical capacity, such that they could have factually contributed to the plaintiff’s loss, and who are not and cannot, therefore, named by the plaintiff as ‘concurrent wrongdoers’. Accordingly, any contractual indemnity arrangements in place between those parties will not be affected by the operation of Part IVAA. 31. Whilst from a policy perspective permitting contractual rights of contribution (as between defendants) generally will either defeat or significantly undermine the purpose of implementing a system of PL7; in the context of voluntary contractual arrangements (and particularly those involving larger scale or sophisticated commercial transactions) section 24AJ, on its current form does not enable parties to contractually arrange the risks of those transactions as between themselves in a way that is likely to be enforced by the Victorian Courts. 7 As noted by Professor Davis as a general rule there can be no right of contribution between various defendants as they will not be liable to the plaintiff for any more than their proper share of responsibility – Inquiry Into the Law of Joint and Several Liability: Report of Stage Two (Commonwealth of Australia, 1994, 1995), p.9 9 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 32. This effect, as noted in a paper recently delivered by the Commercial Bar Association, runs counter to the policy intent of implementing PL to alleviate the pressure on insurance premiums: “One of the ways in which commercial parties arrange their affairs is to require parties contracting with them to provide a full indemnity and to carry insurance for any loss. Why would the legislation cut across that arrangement, thereby increasing the risk of creating an uninsured defendant?” 8 33. While the above examples are merely hypothetical scenarios of how PL might operate in practice (in the absence of any court’s judgment), they illustrate the potential of Part IVAA to undermine the commercial value of contractual allocation of risk in major contracts. 34. It should be noted that at this stage, it is difficult to quantify to what extent the operation of the current PL provisions do negatively impact on the general business environment in Victoria – particularly as to whether or not these provisions have imposed added costs or burdens on Victorian businesses. The Victorian Government is keen to obtain organisational and industry views on the actual or perceived costs of the inability of parties to manage the commercial allocation of risk as a result of the implementation of Part IVAA. Further, the Victorian Government is keen to obtain stakeholder views as to whether any amendment to the legislation to allow the enforcement of contractually assumed risk will provide greater benefits or impose further costs from a stakeholder perspective. 8 Uren A.G. and Aghion D., ‘Proportionate Liability: An Analysis Of The Victorian And Commonwealth Legislative Schemes’, Commercial Bar Association Paper for CLE Seminar dated 18 August 2005 10 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 Question 1: Should the Act be amended to enable contractually assumed allocations of risk to be enforceable despite the operation of Part IVAA? Question 2: Would an amendment that enables the enforcement of contractually assumed allocations of risk despite the operation of Part IVAA provide greater benefits for or add greater costs to conducting business in Victoria? Question 3: Aside from the potential problems with enforcing contractually assumed risk under Part IVAA are there any other problems that can be identified with Part IVAA in relation to managing the contractual allocation of risk? 11 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 D. Options for Amending Part IVAA to Enable Voluntary Allocation of Risk under Contract 35. In light of the above discussion, certain options for amending Part IVAA have been raised for consideration. The primary options currently being considered by the Victorian Government are: • Option 1 - Insert a provision into the Act which allows contracting parties to ‘contract out’ of the application of Part IVAA (similar to the Western Australian or NSW legislation); or • Option 2 - Insert in section 24AI of the Act a provision to the effect that a Court must have regard to any contractually assumed responsibility for the purposes of determining the extent of a defendant’s ‘responsibility’ for loss or damage. Option 1: Allow parties to contract out of Part IVAA 36. Section 4A of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (WA) (‘the WA Act’) provides that a written agreement signed by the parties to it may contain an express provision by which a provision of various Parts of the WA Act, including Part 1F (proportionate liability) can be excluded, modified or restricted, and the WA Act does not limit or otherwise affect the operation of that express provision. 37. Accordingly, in Western Australia, parties can ‘contract out’ of the proportionate liability provisions, and include in their contracts a clause which states for the purpose of a court determining ‘responsibility’ for liability under Part 1F of the WA Act, any agreement to allocate liability between the parties is to be given preference. 38. NSW has a similar exemption in its Civil Liability Act 2002 (‘the NSW Act’). Section 3A(2) provides that ‘[t]his Act (except Part 2) does not prevent the parties to a contract from making express provision for their rights, obligations and liabilities under the contract with respect to any matter to which this Act applies and does not limit or otherwise affect the operation of any such express provision’. As with the WA Act, this provision indicates that parties are able to stipulate in contracts allocating liability for loss that parties are only bound by all or part of Part 4 (Proportionate Liability) to the extent that it is consistent with their assumption of liability under the contract. 39. The advantage of this option is that it allows Part IVAA to remain intact, and simply ensures that parties who wish to retain their right to contractually allocate risk as between themselves can do so with certainty. Accordingly, parties retain the freedom to determine the extent to which Part IVAA will not apply, which is arguably beneficial since it may be the case that in some situations parties do not wish to ‘contract out’ of the Part in its entirety or in every regard. 40. For example, parties might wish to provide in a contract that a determination as to their liability under Part IVAA does not prevent them from enforcing any contractual indemnity arrangements or allocations of risk as between them. If this were the case with regards to Scenario 2 (see Attachment 3), then whilst D1, D2 and D3 12 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 might be found liable by a court to the same extent as their factual/causal liability, they would subsequently be able to overcome the problems associated with s24J and recover a contribution from each other according to the terms of their contractual allocation of risk. However it would not necessarily prevent a court from finding the relevant defendants liable to a plaintiff in the first instance. 41. In order to achieve this option, a provision could be inserted into Part IVAA (for example after section 24AI(3) that is similar to s4A of the WA Act; or s3A(2) of the NSW Act. This option should, in effect, represent a return to the pre-Part IVAA general law position restoring solidary liability in cases of negligence, where parties have contractually provided for it. However, it should be noted that by making express provision in the Act for parties to contract out of Part IVAA, the legislative position in Victoria will diverge from the legislative position in most other jurisdictions.9 42. It should also be noted that Option 1 may not necessarily remedy a situation (such as in Scenario 2) from a plaintiff’s perspective where P’s contract with D1 does not contain a contracting out clause for the purposes of Part IVAA. In such a case, Part IVAA would continue to apply to P’s claim but would not apply to D1 and D2 due to the contract indemnifying D1 for any liability. While D1 may be 50% responsible on a factual basis and D2 only 30%, with ‘contracting out’ D2 is assuming legal responsibility for D1 and, in effect, total responsibility of 80%. 43. Where D2 is either a ‘shell company’ established by D1 for such a purpose, or is a small sub-contractor with little capacity to meet such liability, then P is at risk of recovering little or no compensation for its losses. This situation would not ordinarily occur where the parties are sophisticated transactors and the plaintiff has obtained legal advice on the proposed transaction or undertaken the necessary due diligence. However, where the plaintiff is a smaller business or is an individual who may not have the level of commercial sophistication or resources to investigate D1’s commercial arrangements prior to entering into the transaction, there is a risk that the plaintiff will not be protected by Option 1 in the event of economic loss. The outcome for the plaintiff will depend on the nature of the transaction and on other applicable laws governing the conduct or formation of that transaction – for example a requirement that parties to that type of transaction hold some form of public liability or professional indemnity insurance. 44. A variation on adopting a ‘blanket’ contracting out approach out may involve an express contracting out provision in combination with a ‘threshold’. This variation is intended to limit the class of contractual arrangements to which an express contracting out provision would apply. For example, if it is demonstrated that only commercial transactions of a certain type or sophistication (eg major projects involving a number of parties) are likely to be undermined by the current PL provisions, it may be appropriate to insert a suitable provision that allows contracting out but only if the value of the contract is, as an example, above a certain monetary threshold. A threshold would, in-principle, represent a more limited departure from the general application of Part IVAA in Victoria. 9 The Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) and the relevant legislation in Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory do not expressly provide for the contracting out of proportionate liability. 13 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 Option 2: State that a court must have regard to any contractual arrangements between concurrent wrongdoers when applying Part IVAA 45. This option would ensure that in allocating a proportion of damages to a concurrent wrongdoer, any contractual assumption of risk must be considered and potentially factored into the court’s determination of that concurrent wrongdoer’s extent of ‘responsibility’. This means that if a court finds that in fact, a concurrent wrongdoer’s causal liability contributed only 5 per cent towards the plaintiff’s loss that 5 per cent may be increased or reduced to reflect the extent of responsibility the relevant contract states the concurrent wrongdoer will assume if a plaintiff suffers loss. 46. This option therefore clarifies the meaning of ‘responsibility’ so that when courts apportion responsibility between wrongdoers, ‘causal liability’ is considered alongside contractually allocated liability. Further, this option would signal a legislative intention to ‘single out’ or ‘highlight’ contractual arrangements for special consideration by a court when applying Part IVAA, although it falls short of an explicit statutory exemption. 47. The advantage of this option is that it is conceivable that in some cases a concurrent wrongdoer should be found liable to a greater or lesser extent than precisely what their contract stipulates. Arguably, the court should have the discretion to override contractual liability (to some extent) or at least to apply a flexible approach to cases where there is a manifest discord between the contractual allocation of risk and a defendant’s ‘moral responsibility’ for causing a loss. 48. From a policy perspective, this option would remain more consistent (than Option 1) with the underlying principles of PL (as discussed in Part B) in that a court would be required to consider both contractually assumed liability and causal liability. The allocation of liability by a court under this option would then reflect what is ‘just’ in the particular circumstances of individual cases. 49. However, this option would not provide statutory certainty as to whether or not a court’s final determination would place greater weight on the causal liability of a concurrent wrongdoer or the contractually assumed liability of that concurrent wrongdoer for the purposes of assessing damages. This is because the words ‘must have regard to’ simply mean that a court is bound to consider the relevant terms of a contract, but not necessarily strictly enforce those terms. In contrast to Option 1, the determination of ‘responsibility’ is at the court’s discretion and this arguably may encourage parties to seek to litigate disputes in order to reduce their contractual liability. 50. Moreover, this option should be considered in light of the need to clarify the current legislative uncertainty over parties’ freedom to contract (in relation to risk allocation) and in light of other existing remedies that serve to protect ‘weaker’ parties against the inequalities in bargaining power (for example, the application of general equitable doctrines such as unjust enrichment, unconscionability, undue influence etc). 51. It should also be noted that this Option may not overcome the problems associated with section 24AJ, insofar as concurrent wrongdoers still would not be able to seek 14 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 a contribution from each other once judgment has been given as to their respective liability to the plaintiff. It simply indicates that when determining the amount of damages for which concurrent wrongdoers are liable, that amount would be adjusted to some extent in the light of any contract as to liability. Therefore, indemnities would remain unenforceable where inconsistent with the court’s apportionment of factual liability. 52. A variation on Option 2 could be the insertion of a provision that states the court must apply the terms of a contract (as opposed to ‘have regard to’) when determining responsibility under Part IVAA. This method seeks to remove the discretion available to a court under Option 2 when examining the responsibility of the defendant. From a policy perspective, this variation signals a more complete departure from the application of the PL principles. 53. While this variation is a different mechanism from an express contracting out provision (as considered in Option 1) the variation, in effect, seeks to achieve a similar outcome to Option 1. The intention of the legislation would be to preclude a court from considering causal liability of a concurrent wrongdoer to the extent that the relevant contractual term provides otherwise. 15 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 Question 4: Does Option 2 provide an appropriate balance between the proportionality principle and the need to protect the contractual assumption of risk? Should this option be varied so that a court must apply the terms of the relevant contract when apportioning liability under Part IVAA? Question 5: Which of Options 1 and 2 would provide the most appropriate solution to address concerns over the interaction of Part IVAA and contractual arrangements to allocate risk? Question 6: Are there any other options which provide a more appropriate balance between the intended general operation of Part IVAA and protecting contractual arrangements to allocate risk? Will those other options provide sufficient statutory certainty to contracting parties? 16 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 E. Current Retrospective Effect of Part IVAA 54. Currently, section 24AS of the Act provides that Part IVAA applies to proceedings that are commenced in a court on or after the commencement of section 3 of the Wrongs and Limitation of Actions (Insurance Reform) Act 2003. As a result, relevant proceedings brought on or after 1 January 2004 are subject to the PL provisions. However, section 24AS, as currently framed, allows Part IVAA to have general retrospective effect to a cause of action (whether in tort, contract or under statute) that has accrued prior to 1 January 2004. 55. This gives rise to a situation whereby any pre-existing contractual arrangements allocating liability risk between parties (i.e. contracts entered into prior to 1 January 2004) may be overridden by Part IVAA if proceedings relating to those contractual arrangements are commenced after 1 January 2004. The Victorian Government is aware that this provision potentially adds uncertainty to those commercial transactions with contractual arrangements purporting to allocate risk which were entered into prior to Part IVAA taking effect. 56. Accordingly, to maintain consistency with any decision taken to protect the voluntary allocation of risk pursuant to contract, consideration will also be given as to whether or not an appropriate amending provision ought to be inserted to limit the application of Part IVAA to contracts entered into after the commencement of Part IVAA. 57. As the purpose of this review relates solely to the clarification and protection of contractual arrangements allocating liability risk, it is not envisaged that the review of section 24AS include claims for economic loss arising purely in tort or under statute. Question 7: Should an appropriate savings provision also be drafted to provide that Part IVAA only applies to contracts entered into after the commencement of Part IVAA? 17 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 ATTACHMENT 1 WRONGS ACT 1958 s. 24AE 24AF S. 24AE inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3 (as amended by No. 102/2003 s. 36). PART IVAA—PROPORTIONATE LIABILITY 24AE. Definitions In this Part— "apportionable claim" means a claim to which this Part applies; "court" includes tribunal and, in relation to a claim for damages, means any court or tribunal by or before which the claim falls to be determined; "damages" includes any form of monetary compensation; "defendant" includes any person joined as a defendant or other party in the proceeding (except as a plaintiff) whether joined under this Part, under rules of court or otherwise; "injury" means personal or bodily injury and includes— (a) pre-natal injury; and (b) psychological or psychiatric injury; and (c) disease; and (d) aggravation, acceleration or recurrence of an injury or disease. S. 24AF inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3 (as amended by No. 102/2003 s. 37). 24AF. Application of Part (1) This Part applies to— (a) a claim for economic loss or damage to property in an action for damages (whether in tort, in contract, under statute or otherwise) arising from a failure to take reasonable care; and (b) a claim for damages for a contravention of section 9 of the Fair Trading Act 1999. (2) If a proceeding involves 2 or more apportionable claims arising out of different causes of action, liability for the apportionable claims is to be determined in accordance with this Part as if the claims were a single claim. (3) A provision of this Part that gives protection from civil liability does not limit or otherwise affect any protection from liability given by any other provision of this Act or by another Act or law. 18 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 24AG. What claims are excluded from this Part? (1) This Part does not apply to claims arising out of an injury. (2) Without limiting sub-section (1), this Part does not apply to the following— S. 24AG inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3. s. 24AH 24AI (a) a claim to which Part 3, 6 or 10 of the Transport Accident Act 1986 applies; (b) a claim to which Part IV of the Accident Compensation Act 1985 applies; (c) a claim in respect of an injury which entitles, or may entitle, a worker, or a dependant of a worker, within the meaning of the Workers Compensation Act 1958 to compensation under that Act; (d) a claim for compensation under Part V of the Country Fire Authority Act 1958 or a claim for compensation under a compensation scheme established under the regulations made under that Act; (e) an application for compensation under Part 4 of the Victoria State Emergency Service Act 2005; (f) a claim for compensation under Part 6 of the Emergency Management Act 1986; S. 24AG(2)(e) substituted by No. 51/2005 s. 58(10). (g) an application for compensation under the Police Assistance Compensation Act 1968; (h) an application for assistance under the Victims of Crime Assistance Act 1996; (i) a complaint under the Equal Opportunity Act 1995; (j) a claim for compensation under Part 8 of the Juries Act 2000 or Part VII of the Juries Act 1967; (k) a claim for compensation under Division 6 of Part II of the Education Act 1958. (3) This Part does not apply to claims in proceedings of a class that is excluded by the regulations from the operation of this Part. 24AH. Who is a concurrent wrongdoer? (1) A concurrent wrongdoer, in relation to a claim, is a person who is one of 2 or more persons whose acts or omissions caused, independently of each other or jointly, the loss or damage that is the subject of the claim. S. 24AH inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3. (2) For the purposes of this Part it does not matter that a concurrent wrongdoer is insolvent, is being wound up, has ceased to exist or has died. 24AI. Proportionate liability for apportionable claims (1) In any proceeding involving an apportionable claim— (a) the liability of a defendant who is a concurrent wrongdoer in relation to that claim is limited to an amount reflecting that proportion of the 19 S. 24AI inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3. Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 loss or damage claimed that the court considers just having regard to the extent of the defendant's responsibility for the loss or damage; and s. 24AK (b) judgment must not be given against the defendant for more than that amount in relation to that claim. (2) If the proceeding involves both an apportionable claim and a claim that is not an apportionable claim— (a) liability for the apportionable claim is to be determined in accordance with this Part; and (b) liability for the other claim is to be determined in accordance with the legal rules, if any, that (apart from this Part) are relevant. (3) In apportioning responsibility between defendants in the proceeding the court must not have regard to the comparative responsibility of any person who is not a party to the proceeding unless the person is not a party to the proceeding because the person is dead or, if the person is a corporation, the corporation has been wound-up. S. 24AJ inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3. 24AJ. Contribution not recoverable from defendant Despite anything to the contrary in Part IV, a defendant against whom judgment is given under this Part as a concurrent wrongdoer in relation to an apportionable claim— (a) cannot be required to contribute to the damages recovered or recoverable from another concurrent wrongdoer in the same proceeding for the apportionable claim; and (b) cannot be required to indemnify any such wrongdoer. S. 24AK inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3. 24AK. Subsequent actions (1) In relation to an apportionable claim, nothing in this Part or any other law prevents a plaintiff who has previously recovered judgment against a concurrent wrongdoer for an apportionable part of any loss or damage from bringing another action against any other concurrent wrongdoer for that loss or damage. (2) However, in any proceeding in respect of any such action the plaintiff cannot recover an amount of damages that, having regard to any damages previously recovered by the plaintiff in respect of the loss or damage, would result in the plaintiff receiving compensation for loss or damage that is greater than the loss or damage actually suffered by the plaintiff. S. 24AL inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3. 24AL. Joining non-party concurrent wrongdoer in the action (1) Subject to sub-section (2), the court may give leave for any one or more persons who are concurrent wrongdoers in relation to an apportionable claim to be joined as defendants in a proceeding in relation to that claim. (2) The court is not to give leave for the joinder of any person who was a party to any previously concluded proceeding in relation to the apportionable claim. 20 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 24AM. What if a defendant is fraudulent? Despite sections 24AI and 24AJ, a defendant in a proceeding in relation to an apportionable claim who is found liable for damages and against whom a finding of fraud is made is jointly and severally liable for the damages awarded against any other defendant in the proceeding. 24AN. Liability for contributory negligence not affected Nothing in this Part affects the operation of Part V or Division 7 of Part X. 24AO. Effect of Part IV Except as provided in section 24AJ, nothing in this Part affects the operation of Part IV. S. 24AM inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3. s. 24AQ 24AM S. 24AN inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3 (as amended by No. 102/2003 s. 38). S. 24AO inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3. S. 24AP inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3. 24AP. Part not to affect other liability Nothing in this Part— (a) prevents a person from being held vicariously liable for a proportion of any apportionable claim for which another person is liable; or (b) prevents a person from being held jointly and severally liable for the damages awarded against another person as agent of the person; or (c) prevents a partner from being held jointly and severally liable with another partner for that proportion of an apportionable claim for which the other partner is liable; or (d) prevents a court from awarding exemplary or punitive damages against a defendant in a proceeding; or (e) affects the operation of any other Act to the extent that it imposes several liability on any person in respect of what would otherwise be an apportionable claim. 24AQ. Supreme Court—limitation of jurisdiction It is the intention of sections 24AI and 24AL to alter or vary section 85 of the Constitution Act 1975. 24AR. Regulations (1) The Governor in Council may make regulations generally prescribing any matter or thing required or permitted by this Part to be prescribed or necessary to be prescribed to give effect to this Part. (2) The regulations— (a) may leave any matter to be determined by the Minister; and (b) may apply, adopt or incorporate, wholly or partially or as amended by the regulations, any matter contained in any document as existing or in force— (i) from time to time; or (ii) at a particular time. 21 S. 24AQ inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3. S. 24AR inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3. Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 S. 24AS inserted by No. 60/2003 s. 3. 24AS. Transitional This Part applies to proceedings that are commenced in a court on or after the commencement of section 3 of the Wrongs and Limitation of Actions Acts (Insurance Reform) Act 2003. _______________ 22 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 ATTACHMENT 2 HYPOTHETICAL CONTRACTUAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR SALE OF LIGHTHOUSE SCENARIO 1 – INDEMNITY CONTRACT BETWEEN PLAINTIFF AND A DEFENDANT P contracts with D1 to build light house. Contract between P and D1 provides that D1 will indemnify P for 100% of any loss incurred. D1 sub-contracts with D2 to install structural supports for the lighthouse. The lighthouse collapses after P takes possession of the lighthouse. P sues D1 for economic loss or damage to property. D1 joins D2 to the action. On factual enquiry, a court might find D1 was 20% responsible and D2 was 80% responsible for P’s loss. Actual / Causal Liability Liability outcome under Part IVAA Liability outcome prior to PL and under Option 1 D1 – 20 % D1 – 20 % D1 – 100% D2 – 80 % D2 – 80 % 23 Review of Contractual Allocation of Risk and Part IVAA of the Wrongs Act 1958 ATTACHMENT 3 HYPOTHETICAL CONTRACTUAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR SALE OF LIGHTHOUSE SCENARIO 2 – INDEMNITY CONTRACT BETWEEN DEFENDANTS P contracts with D1 to build a light house. D1 sub-contracts with D2 to construct the light house. D2 agrees to indemnify D1 for 100% of any loss incurred by D1. D2 contracts with D3 to supply materials. The lighthouse collapses after P takes possession of the lighthouse. P sues D1 for economic loss or damage to property. D1 joins D2 and D3 to the action. On factual enquiry, a court might find D1 was 50% responsible for P’s loss, D2 was 30% responsible and D3 was 20% responsible. Under s24AJ D1 cannot subsequently seek contribution from D2. Actual / Causal Liability Liability outcome under Part IVAA Liability outcome prior to PL and under Option 1 D3 – 20 % D3 – 20 % D3 – 20 % D2 – 30 % D2 – 30 % D2 – 80% D1 – 50 % D1 – 50 % 24