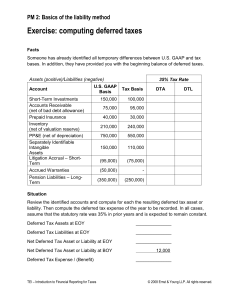

Book-Tax Differences: Which Ones Matter to Equity Investors?

advertisement