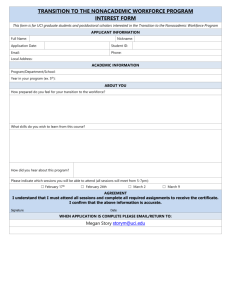

academic workforce planning —towards 2020

advertisement