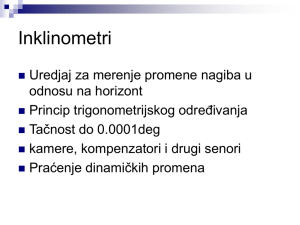

Use of Inclinometers for Geotechnical Instrumentation on

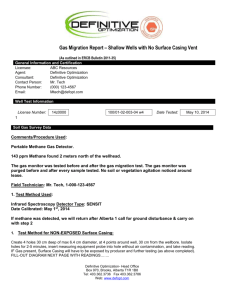

advertisement