Part I: The Need for a USTA/ITA Player Rating System

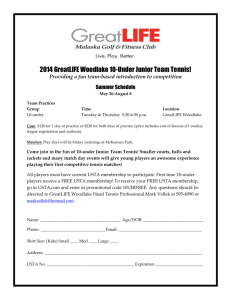

advertisement