Children's Advertising Appeals NCA

advertisement

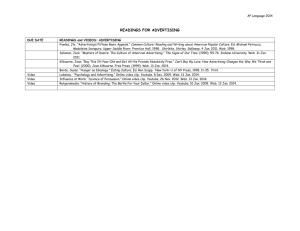

STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 1 From Barbie and Sponge Bob to Body Image and Sex: Advertising Appeals to Teenagers, Adolescents and Children Children and teens are extremely powerful. They have the ability to make billions of dollars in spending decisions, sway the opinions of their peers, influence the values, habits, and behaviors of their parents and family members (McNeal, 1991; Ritson & Elliott, 1999; Wilcox et al., 2004). Such power makes these individuals desired target audiences of marketers across the United States. In fact, children and teens are so influential that marketers estimate they make over $500 billion in family expenditures every year (Moore, 2004; Wilcox et al., 2004). According to Kennedy (1995), marketers see children in several ways: as individual purchasers, as influencers of family purchase decisions, as individuals parents spend money on, and as individuals spending money in the future. Because of this, billions of dollars are spent on advertising and marketing campaigns every year, in the hopes of affect present and future familial spending habits. In fact, in 2002 alone, more than $15 billion was spent in promoting products and services to children in the United States (Center for Science in the Public Interest, 2003; McNeal, 1998), and this amount was not without a profit for marketers. On average, spending on teens yields a 2-to-1 direct return on advertising dollars spent (McNeal, 1998; Moore, 2004). In the past, children were not considered an important target audience to advertisers (Wilcox et al., 2004). However, as both the market and advertisers became more savvy, and methods of communication expanded, this has slowly changed and advertisers are targeting children at a younger age each year (Linn, 2004). Advertising targeted specifically to children and teens did not become a common practice until cable STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 2 television and child-oriented programs became a household staple in the 1970’s and 1980’s (Wilcox et al., 2004). Today, the average American child sees roughly 40,000 commercials on television every year (Linn, 2004; Preston & White, 2004; Wilcox et al., 2004), selling anything and everything from Cocoa Puffs to power tools. When comes to advertising to children, the effects of advertising to children has been thoroughly explored; however, little research has examined the content of advertisements (Jennings & Wartella, 2007). The appeals to children have been examined as well, and studies have indicated that the emotional appeals tend to have greater effect on children (Huhmann & Brotherton, 1997; Jennings & Wartella, 2007; Mangleburg & Bristol, 1998) than many of the other advertising appeals that advertisers use (Mueller, 1987). According to marketing and advertising industry leaders, the appropriate age at which to actively sell products to children correlates with the age that they believe the young person can make an intelligent choice, which can be as early as five- to sevenyears-old (Eagle, 2007; Jennings & Wartella, 2007). Research has also indicated that marketers feel a child can view advertising critically, as well as separate fantasy from reality by age 9, and then make intelligent choices as consumers by age 11 (Eagle, 2007; Geraci, 2004; Kunkel, 2005). This view has received criticism by scholars for taking undue advantage of children’s unique vulnerabilities and lack of critical thinking skills (Avery, 1979; Huhmann & Brotherton, 1997; Kelly & Chapman, 2007; Kelly, 1974; Krugman & Whitehill King, 2000; Macklin, 1987; Moore, 2004; Preston & White, 2004). This lack of critical thinking skills and inundation of advertising messages has led many researchers to examine the affect advertisements have on perceptions, cognitive development, and attitudes of youths (Brooker, 1981; Friestad & Wright, 2005; Henke, STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 3 1995; Kelly, 1974; Kennedy, 1995; Moore & Lutz, 2000; Pechmann, Levine, Loughlin, & Leslie, 2005; Peterson, 2005; Smith, 1995; Wackman & Wartella, 1977). Previous studies relating to advertising and children primarily focus on television and the effects related to it (Brooker, 1981; Krugman, 2000; Moore & Lutz, 2000; Moore & Moschis, 1978; Roedder, Sternthal, & Calder, 1983). It is worthy to note that most empirical literature on children’s understanding of advertising is based on their relationship to television advertising and does not examine advertising in children’s magazines (Friestad & Wright, 2005; Moses & Baldwin, 2005). Studies that have investigated advertising in relation to children and teens magazines examined the imagery of advertisements, crosscultural implications of the advertisements (Jeon, Franke, Huhmann, & Phelps, 1999; Maynard & Taylor, 1999), appeal types within advertisements (Boush, Friestad, & Rose, 1994; Huhmann & Brotherton, 1997; Peterson, 1994), and the unique vulnerability of children in relation to viewed advertisements (Heinzerling, 1992; Weisskoff, 1982). Other research has concentrated on persuasion and skepticism of advertisements for children (Mangleburg & Bristol, 1998; O'Donahoe & Tynan, 1998). However, such research has led some researchers to voice concern over the practice of targeting adolescents. As Pechmann et al. stated (2005), “adolescents’ psychological immaturity, or weak inhibitory control, is a significant predictor of their risky decisions and actions” (p. 207), leading some adolescents with weak defense mechanisms to be susceptible to advertising with controversial themes, potentially leading to unhealthy or reckless decisions (Peterson, 2005). One of the most influential theories that has emerged in research regarding advertising and children, whether television or magazines, is Piaget’s (Piaget, 1926, STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 4 1929) stage theory of cognitive development. This theory, which posits that children’s cognitive ability gradually develops through “a series of stages which are differentiated qualitatively in terms of the types of cognitive structures present. The developmental process is dependent on maturation, but it also depends on the child’s experience, since the child is an active agent who tries to cope with his environment and, in this process, developed new structure and new organizations” (Wackman & Wartella, 1977, p. 205). In other words, children’s ability to process information goes through a series of stages that, as they grow older, allow them to process and understand more complex information and messages (Perry, 2002; Piaget, 1970). In his work, Piaget posited that children are born with pre-established schema, or reflexes, which they use to learn about their environment. He hypothesized that as children age, the schema that which are ingrained within them become more complex. Eventually, the complexity of the schema develops, become structures, and hierarchal behaviors occur (Piaget, 1972). This happens gradually, over a period of stages that develop as the intelligence of the child develops. Each stage represents the understanding of reality for the child. As time progresses, several factors, such as peer interaction, understanding of their environment, and accumulation of knowledge, help develop a child’s understanding of reality (Piaget, 1972). According to Piaget, this process can be categorized into four distinct, sequential levels: the sensorimotor period (0-2 years), preoperational (2-7 years), concrete operational (7-11 years), and formal operational (11+ years) (Kennedy, 1995; Piaget, 1926, 1953, 1970; Smith, 1995). These four stages take a child from infancy through STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 5 preschool, childhood, and eventually adolescence. It is important to note that the ages assigned to these stages are guidelines, which can vary depending on the individual development of the child (Kelly, 1974; Kennedy, 1995). The earliest stage of cognitive development is the period of sensorimotor intelligence, which is categorized from birth through two years, primarily as infancy. This stage is one in which infants gain knowledge from the world around them through simple perceptual and motor adjustments. Knowledge of the outside world and perceptions of other viewpoints is extremely limited, as their world is based on their physical experiences (Kennedy, 1995; Wackman & Wartella, 1977). Typically, the sensorimotor period consists of a series of six substages: simple reflexes, primary circular reactions, secondary circular reactions, coordination of secondary circular reactions, tertiary circular reactions, and internalization of schemes (Piaget, 1972). First, in the reflexive stage, the child learns simple reflexes, such as grasping or sucking during the first two months of life. Between 2-4 months, children begin having primary circular reactions to their environment, doing reflexive behaviors that encompass repetitive movements or actions, such as smiling or opening and closing their hands. At 4-8 months, secondary circular reactions to their environment begin to occur, such as reaching for a rattle to shake it. It is at this stage that a child begins to act intentionally, and is aware of objects other than themselves (Inhelder & Piaget, 1964; Piaget, 1953). At 8-12 months, a child begins to coordinate secondary reactions, understand permanence of objects, and can combine their understanding of different schemas to reach a goal. For example, if a child wanted to reach a toy on a blanket, but were unable to reach the toy itself, they may use the blanket to pull the toy closer to them. If that same toy were STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 6 hidden under a blanket, the child would understand the toy was still there and would possibly move the blanket to retrieve it. Tertiary circular reactions develop at 12-18 months, and the child begins to try different ways to accomplish different goals. In the final substage of the sensorimotor period, children between the ages of 18-24 months begin to internalize and symbolize their thought processes, and develop language skills (Piaget, 1953; Piaget, 1972). Children in the sensorimotor stage of cognitive development typically are not a targeted be advertiser, simply for their lack of cognitive awareness. However, the parents of children at this stage are bombarded with materials to help their child become more intelligent. For example, Baby Einstein, myNoggin, and Brainy Babies all imply certain cognitive attributes will be bestowed upon children who watch them. (Linn, 2004). Whether these “educational” materials are actually beneficial to children is currently a topic of debate among scholars and media producers. The second stage of cognitive development is known as the preoperational stage of cognitive development. In this stage, children between the ages of two through seven can begin to interact with and manipulate symbols around them (Piaget, 1970; Wackman & Wartella, 1977). Language skills at this age group are very limited and thought processes are based on non-verbal cues and mental images rather than the meaning of words (Bahn, 1986; Smith, 1995). Thinking at this level is egocentric. However, the egocentricity of the child diminishes as the child develops. Children in this phase also have difficulty understanding the viewpoints of others (Piaget, 1929). The preoperational stage is typically divided into two substages known as true preoperational phase and an intuitive phase. The preoperational substage is typically STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 7 shared by children ages 2 to 4 years old (Piaget, 1955). It is at this stage that verbal skills grow and imaginative play begins. The second subphase of the preoperations stage of cognitive development is the intuitive phase, for which children usually enter in to from age 4 through age 7. It is in this stage that the child begins to become less egocentric and can understand other viewpoints. During this phase, children begin to develop more social speech patterns, yet have tendencies to still focus attention on one object or action while ignoring their surroundings. In this phase, children are rules-based, as their perceptions of right and wrong are not completely developed. Perceptions of reality and fantasy are still extremely fluid, as children at this age tend to believe in magic explaining the workings of the world (Piaget, 1955). For example, children’s belief of Santa Claus is strongest during this phase. Studies of children at this developmental stage indicate that children below the age of five cannot distinguish program from commercial content and base brand preferences solely on visual cues and modeling (Bahn, 1986; John & Sujan, 1990; Smith, 1995; Wilcox et al., 2004). Research has indicated that most children younger than seven or eight can not recognize persuasive advertising messages or appeals (Wilcox et al., 2004). The third stage of cognitive development, also known as concrete operational, is where children ages seven to 11 begin to discern between central and peripheral information (Kelly, 1974; Wackman & Wartella, 1977). Occasionally, children as young as five can enter into this stage, depending on the intelligence of the child. It is at this level the child can begin to process logically and the child can think in categorical terms (Piaget, 1929). Egocentricity also greatly diminishes, as sociocentricity and operational STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 8 thinking develops. At this stage, elementary school children and early adolescents become capable of concrete problem-solving, such as understanding various concepts in mathematics and science, and are also able to classify objects into logical sequences (Mehler & Bever, 1967). This may be the earliest stage that children can understand the advertising appeals used to gain their attention (Bahn, 1986). The final stage of cognitive development is know as formal operational, which focuses on the cognitive abilities of children aged 11 to 15 and older (Smith, 1995). At this level, the adolescent can use abstract thinking and conceptualization to understand the messages within their environment, and can reflect upon them (Chan & McNeal, 2006; Kelly, 1974; Piaget, 1970). Adolescents can understand proportions, thinking becomes less tied to concrete reality, and the ability to cultivate abstract thinking develops. However, some individuals are not able to develop these formal thinking skills until adulthood, or their early 20’s—sometimes not at all. Operational thinkers can recognize problems, find various solutions, and test the hypotheses (Piaget, 1970). Adolescents at this stage my be able to fully understand advertisements and differentiate them from content in messages they view (Bahn, 1986). Methodology Research Questions Just as adults can fall prey to misleading advertising, so can children. To understand advertising, children—whose mental capacity has not necessarily developed to a level that can discern between informative and deceptive advertising messages— must be able to distinguish advertisements from surrounding program content and understand the persuasive intent and appeals in advertising in order to understand the STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 9 message (Moses & Baldwin, 2005). This exploratory study was conducted to establish an understanding of advertisements in children and teen magazines in relation to children’s developmental processes (Bahn, 1986). Piaget’s stage theory of cognitive development is applied to children’s magazines, assisting this study to examine how advertising appeals are used to reach the target audience. Thus, the following research questions were posed: RQ1: How does the content/appeal of the advertising reflect each of the Piagetian stages for the different magazines? RQ2: Do advertisers in children’s magazines follow CARU guidelines and pitch their appeals at the corresponding Piagetian levels? These questions were used to guide the collection of the data and help define the parameters of the content analysis. Content Analysis Content analysis was chosen as the method for this study due to the generalizability to the larger population (Ford, Kramer Voli, Jr., & Casey, 1998; Huhmann & Brotherton, 1997; Kassarjian, 1977). The advertisements used for this exploratory study came from a stratified random sample of children’s and teen’s magazines published in the spring and fall of 2008. Data from MRI’s Teen Mark 2000 Report were used to generate a list of consumer magazines targeted toward children and teens (Mediamark Research, 2000). Initially, this yielded a list of 112 magazines. These magazines were then classified into four categories based on Piaget’s stages of development (Kennedy, 1995; Piaget, 1953; Wackman & Wartella, 1977; Ward, Wackman, & Wartella, 1977), as well as the characteristics of the magazine and the target audience. These categories were defined as preoperational/kids, concrete STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 10 operational/teen heartthrob, and formal operational/teen fashion magazines. As previously discussed, the sensorimotor stage of cognitive development primarily focuses on an infant’s ability to gain knowledge through simple perceptual and motor adjustments (Kennedy, 1995; Wackman & Wartella, 1977). This initial stage of sensorimotor was excluded from this parameters of this study due to the likelihood that infants and children under the age of two would not be reading magazines at this stage (Bahn, 1986). Upon examination, none of the magazines indicated children under the age of two to be a target audience, thus it was determined that the sensorimotor stage would not need to be included in the study’s parameters. After the magazines were categorized, the list of magazines was then checked against the Simmons Teen-Adult Combined Study and Simmons Kids Study for accuracy and reliability (Simmons Market Research Bureau, 2002, 2005). A stratified random sample from each of the categories was used to create our magazine population for this study (N=56), as seen in Table 1. The magazines used for this study include: Nick Jr., Fun to Learn, Disney and me, Thomas & Friends, Highlights High Five, Click, Ladybug, Hot Wheels Magazine, Sports Illustrated Kids, dig, Nick, Spongebob Squarepants, Highlights, Ranger Rick, National Geographic Kids, Sparkle World, Barbie, Disney Princess, My Little Pony, Tinkerbell, American Girl, Girls’ Life, kiki, Discovery Girls, Boys’ Life, Hot Wheels Magazine, The Kids Zone, WWE Kids, Baseball Magazine, Miley, Blast Presents Jonas Brothers, Blast Presents Miley, Disney High School Musical, Beckett Hannah Montana, Astrogirl, Bop, Celebrity Spectacular, Disney’s High School Musical, Life Story Movie Magic, Life Story Miley, M, Tiger Beat, J-14, Quizfest, Twist, Pop Star, Shout, six 7/8, Spaces Presents the Jonas Brothers, Teen STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 11 Dream, Vibe Vixen Teen Dream, Teen Vogue, Justine, Teen, Cosmo girl!, Seventeen, Quince, Cicada, and Muslim Girl. Sampling Procedure The unit of analysis for this exploratory research was each advertisement within sample of ads within the magazines. The sample for the content analysis was selected by examining every fourth ad, regardless of size. The ads varied from being full color and located inside the front cover to small, black and white ads that were placed in an advertising section in the back of the magazines. Cardboard subscription inserts were not considered advertisements for this analysis, because they were not paid for by someone other than the publisher, and can be thrown away by the reader. Through this method, 418 (25.89%) of the 1614 total advertisements in the magazines were analyzed. Articles were reviewed for several variables. The coding sheet consisted of 34 variables and employed mainly dichotomous and categorical response options, including types of advertising appeals, product category, the proportions of the ads, and other variables. The majority of the variables yielded descriptive data that helped establish the trends in the various magazines. However, several variables were created based on the Children’s Advertising Review Unit’s standards for advertising to children (Heinzerling, 1992; The Children's Advertising Review Unit, 2003; Weisskoff, 1982), which were established to ensure advertising directed towards children is not “deceptive, unfair, or inappropriate for its intended audience. The standards take into account the special vulnerabilities of children, e.g., their inexperience, immaturity, susceptibility to being misled or unduly influenced, and their lack of cognitive skills needed to evaluate the credibility of advertising” (The Children's STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 12 Advertising Review Unit, 2003, p. 3). Thus, based on clearly established CARU guidelines, the advertisements were examined for indications of deception, the use of stereotypes, the use of celebrities, content that poses a health or safety risk, or promotes inappropriate behavior for the target audience, the product unrealistically enhancing the spokesperson or creating unrealistic expectations about its use, the use of characters in an advertisement in close proximity to an article or editorial content about that character, the clarity that the material presented is an advertisement, and the targeting of children under 12 (The Children's Advertising Review Unit, 2003). These variables were used to establish the complexity of the ads, and if they followed the CARU guidelines. For the collection of data, an arbitrary number was assigned, and a database was set up for each advertisement, which collected the name of the magazine, the date published, the total number of pages per magazine, the page number and location of the advertisement, the size, the visual pallet of the ad, the number of subjects, the celebrities, the brand, the product, level of celebrity involvement, and the dominant advertising appeal (Ford et al., 1998). Two coders also determined the level of appropriateness by examining several factors in the ad, such as the imagery used, the target audience, the message portrayed and the type of product being sold, all considerations of the CARU (The Children's Advertising Review Unit, 2003). Training and Reliability Two graduate students coded all the ads in the sample. Training sessions were conducted to educate both the coders on the variables and refine the coding schema. As in previous research examining advertising in magazines, special emphasis was placed on STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 13 both the textual and visual coding (Ford et al., 1998; Huhmann & Brotherton, 1997; Krugman & Whitehill King, 2000). After the training sessions established the consistency of the schema, the two coders examined separate sets of the remaining advertisements. A subset of 20% of the advertisements was used to test for reliability. The Holsti generalized formula (1969) calculated the inter-coder agreement on each coding category, yielding overall reliability of 91.77%. A majority of the categories had 100% reliability, including: the appropriateness of the product, the appropriateness of the imagery, whether the ad was clearly advertising, whether the ad was intended for a child under the age of 12, whether a character easily recognized by a child was used to sell a product, whether a celebrity was used to sell the product, the magazine type, as well as other nominal variables. Specific reliability for the remaining variables were as follows: 95.45% for the proximity of the celebrity or character to the ad, the pallet, and the location of the ad; 93.18% for the advertisement being intended for the magazine’s target audience; 88.63% for the focus of the gender in the advertisement and whether the ad reflected or enhanced the spokesperson; 86.36% for the total pages, the dominant advertising appeal, and for whether the images were in line with reality; and 81.81% for if the ad was targeted toward a parent, the product category, and whether the advertisement was distributed horizontally or vertically. After the satisfactory reliability was obtained, the data was analyzed. Statistical measures The study coded 418 advertisements in 56 different youth magazines, all the magazines fell into one of seven larger categories (Early Childhood, Kids (non-gender STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 14 specific), Kids (female oriented), Kids (male oriented), Teen Heartthrob magazines, Disney Star Specific, and Teen Fashion magazines. Researchers ran an ANOVA test to examine relationships between composite complexity of an advertisement and Piaget’s cognitive development level of the magazine. Pearson Chi-square distributions were conducted to analyze use of various advertising appeals and Piaget’s cognitive development level of the magazine. Descriptive statistics detailing the findings are also reported. Results The following are the results of the content analysis using the included coding sheet and schema described above. Demographics The 56 magazines used in the study were categorized into one of three developmental stages of cognitive learned based on Piaget’s stage theory of cognitive development: Preoperational (Children and Kids magazines), Concrete Operational (Teen Heart throb magazines), and Formal Operational (Teen Fashion magazines). Of the 418 total advertisements examined, a descriptive analysis shows that 47.2% (n=197) of all cases were within Piaget’s formal operational level of cognitive development, 26.7% (n=112) in the concrete operational level, and 26.1 (n=109) in the preoperational level. ---Insert Table 1 about here --RQ1 examines how the content or appeal of the advertising reflects each of the Piagetian stages for the different magazines. A Pearson Chi-square distribution between advertisement appeal and Piaget’s level’s of cognitive involvement showed significance, c2 (df 20, n=418) = 108.481, p < .05. Descriptive analysis within the distributions shows STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 15 Soft-sell appeals (n=118) to be used 61.9% (n=73) for those magazines defined in Piaget’s formal operational level, versus 25.4% (n=30) and 12.7% (n=15) for magazines defined in Piaget’s preoperational and concrete operational levels, respectively. Sexual appeals (n=29) were used 65.5% (n=19) for those magazines defined in Piaget’s formal operational level, versus 27.6% (n=8) in the concrete operational level and 6.9% (n=2) for magazines defined in Piaget’s preoperational level. Achievement appeals (n=29) were used 75.9% (n=22) for those magazines defined in Piaget’s preoperational level, versus 6.9% (n=2) in the concrete operational level and 17.2% (n=5) for magazines defined in Piaget’s formal operational level. RQ2 asked about whether advertisers in children’s magazines followed CARU guidelines and pitched their appeals at the corresponding Piagetian levels. An ANOVA analysis between the composite complexity of an advertisement, which was determined by the CARU guidelines, and Piaget’s cognitive development level of the magazine showed significance F= 16.2 (df 2), p < .05. A Pearson Chi-square distribution between the use of celebrities in advertisement and Piaget’s level’s of cognitive involvement showed significance, c2 (df 4, n=418) = 46.257, p < .05. Descriptive analysis showed that 45.6% (n=57) of all cases of advertisements containing celebrities (n=125) occurred in magazines defined in Piaget’s concrete operational level. A Pearson Chi-square distribution between the use of the product in the ad unrealistically enhancing the spokesperson for the advertisement (one of the CARU guidelines) and Piaget’s level’s of cognitive involvement showed significance, c2 (df 4, n=418) = 23.09, p < .05. Descriptive analysis showed that 58.5% (n=78) of all cases of STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 16 advertisements containing reflect enhancement (n=135) occurred in magazines defined in Piaget’s formal operational level. A Pearson Chi-square distribution between the use of proximity of a character in the advertisement to a story about the character and Piaget’s level’s of cognitive involvement showed significance, c2 (df 4, n=418) = 44.39, p < .05. Descriptive analysis showed that 43.4% (n=43) of all cases of advertisements containing close proximity (n=99) occurred in magazines defined in Piaget’s concrete operational level, while 37.4% (n=37) occurred in the preoperational level and 19.2% (n=19) occurred in the formal operational level. A Pearson Chi-square distribution between clarity of the advertisement, whether the advertisement appeared to be an advertisement, and Piaget’s level’s of cognitive involvement showed significance, c2 (df 4, n=418) = 14.54, p < .05. Descriptive analysis showed that 48.4% (n=162) of all cases of advertisement clarity, in that the ad is obviously an advertisement, (n=335) occurred in magazines defined in Piaget’s formal operational level, while 26% (n=87) occurred in the concrete operational level and 25.7% (n=86) occurred in the preoperational level. A Pearson Chi-square distribution between targeting children under 12 advertisement and Piaget’s level’s of cognitive involvement showed significance, c2 (df 4, n=418) = 118.86, p < .05. Descriptive analysis showed that 61.9% (n=65) of all cases of advertisements targeting kids under 12 (n=105) occurred in magazines defined in Piaget’s preoperational level, while 31.4% (n=33) occurred in the concrete operational level and 6.7% (n=7) occurred in the formal operational level. STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 17 Discussion & Conclusion Several major findings were uncovered by this research. First, advertisers do use different types of appeals in different Piagetian levels. The different stages of cognitive development that the target audience is currently going through may play a major role in dictating which advertising appeals are used. As research has indicated, children in the analytical or concrete operational stage are able to grasp abstract knowledge, and it is at this stage where advertising begins to emerge in the magazines. (Bahn, 1986; Chan & McNeal, 2006). As the child ages, they develop multidimensional understanding that allows them to reason and focus on the social meaning behind the messages (Chan & McNeal, 2006; Kennedy, 1995; Smith, 1995). The statements are consistent with the study’s findings that sexuality appeals and fear appeals are most often poised to those in the formal operational stage of development. Fear appeals were also used heavily in the formal operational stage of development (50% of the total recorded fear appeals). In general, Preoperational magazines that target children under the age of seven, such as Nick Jr., Girls Life, or Ranger Rick, used hard sell messages, humor, and achievement when portraying advertising messages. The reason for this is likely threefold. First, these ads were primarily for parents who would be actively involved with their child’s education and cognitive development. Perceptive marketers would likely want to take advantage of this and use hard marketing points to sell their product to the parent on a logical level. Second, some advertisers may try to take advantage of a child’s ability to understand a humorous message in the hopes the child would relate such humor to the product itself. Need for achievement is something ingrained in children at a very early age in school as a way to do well in class and to be socially accepted. It is not surprising STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 18 to see advertisements cater to a young child’s want for achievement at such a transitional point in a child’s social development. The concrete operational stage was shown as more of a transitional age between the appeal to preoperational stages and formal operational stages. The exceptions being appeals with celebrity use and body dissatisfaction, however these categories remained at almost identical levels through to the formal operational stage. The analysis of these data indicates that the composite complexity of the ad, which was based off the CARU guidelines, is significantly related to the Piagetian levels of the magazines. Although the complexity of the advertisement does not necessarily vary from Piagetian level to Piagetian level, the type of complexity does change within the group. For example, as kids get older more celebrities and more advertisements are placed in magazines. One noteworthy finding was the use of celebrities in the advertisements. For example, Concrete Operational magazines, which target children between the ages of seven and 11, and is the earliest stage that children can understand advertising appeals (Bahn, 1986), use status/celebrity often in the advertisement, with celebrities as the focus of the sell, even if the celebrity is not in the ad. This may indicate the potential impact that celebrities have on products and purchasing habits. In every magazine level, celebrities were used in ads to sell/promote products. Although most were using the celebrity with low levels of emphasis, there were moderate to high levels of celebrity use found; thus, indicating celebrities are important in ads for all age groups. This finding is not surprising considering the nature of some of the magazines as well as the impact that celebrities can have on adult product purchasing habits. Future research should examine STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 19 the susceptibility of children to messages from celebrities versus characters, and regular endorsers. Children are an important consumer segment, but must be treated with respect and care. Since some children may not fully understand the messages in advertisements targeted towards them, marketers must be careful to not deceive or manipulate them. Although understanding a child’s level of cognitive development may help advertisers develop a better understanding of the group they are targeting, they must also take their responsibility to be fair to that child into consideration. Advertisements that are inappropriate—whether too sexually over, dangerous, unhealthy, or too risky—were found in all groupings. However, overall, ads were found to be appropriate for the target age group. This finding indicates that marketers may attempt to place appropriate ads to the appropriate target audience. Although a few advertisements were not appropriate for the readers of certain magazines, such as sexually overt ads for deodorant—where the beautiful young woman has handsome, half-naked men fawning after her because of her sweet smelling armpits, the majority seemed to consider the child’s cognitive abilities. However, it is not clear what standards of “appropriateness” apply—the child, the parent, the magazine, or the advertiser. Limitations & Future Research One methodological limitation is that certain measures, the factors of cognitive complexity, are based on other research (Bailey, 2007; Basil, 1996; Campbell & Keller, 2003; Shiv, Edell, & Payne, 1997), but are untested and relatively new. Therefore, before any true measures can be established, testing of the coding schema should be conducted to examine reliability. STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 20 Another limitation is that only magazines intended for children and teens were examined. Magazines intended for the young adult or adult audience, such as US Weekly or Playboy, were not analyzed even though there is likely some crossover with readership and many teens attempt to read material that pushes the envelop of their developmental boundaries. Therefore, it is unknown what types of appeals and persuasive messages that adolescents are exposed to when they are reading material that is not intended for them. This research does not take the impact that these messages may have on the young reader into consideration either. A definite limitation to this type of work is that the coders could not perceive the ads from the mind of a child. Although these advertisements were coded for appropriateness and cognitive complexity, it is unknown how a child might interpret an ad, despite adult’s perception of what is appropriate or complex (Bartholomew & O'Donahoe, 2003). Without understanding how a child might view the advertisement, assignments of complexity are merely subjective. Magazines are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to media that children view. Because this research only examined the appeals used in magazine advertisements, and did not take television, radio, and the Internet into consideration, we cannot truly understand the type of messages that a child might receive. This does not allow the research to be generalized outside the medium, or compare the data and the trends within them. Many magazine are not simply reading material, but rather tools to help build brand loyalty, something that is relatively subversive for parents, but an strategic enterprise at the time. Because these media are extremely powerful as well as popular tools of communication, the relationship that magazine have with other media toll should be explored in the future. When examining this research, the sales trends of the STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 21 magazines should also be taken into consideration. In recent years, numerous magazines have stopped production due to poor sales. If the magazine industry is dying off, do the ads have as much significance as an ad on television or the Internet might? Finally, the coding of this data was mostly dichotomous and did not take in the magnitude of the question into consideration. In this study, when an advertisement was coded as have a celebrity, it did not examine the emphasis placed on the celebrity. For example, when Rihanna was in a “Got milk?” ad, she was placed as the main focal point in the advertisement. In this example, Rihanna’s celebrity status and sex appeal created emphasis to attract the attention of the reader. However, when Jessica Simpson was used to promote Proactive skin care, the emphasis was placed on the content of the advertisement and the attributes of the product rather than her power as an endorser. The coding sheet did not take the environment versus the content of the advertisement into consideration. As previously discussed, researchers should expand the framework of this study so that it encompasses more magazines as well as examines them over a longer period of time. Another area worth exploring would be investigating how closely other types of advertisements in children’s magazines follow the CARU guidelines (The Children's Advertising Review Unit, 2003). Although previous work has established the trends in decades before (Heinzerling, 1992; Weisskoff, 1982), it has not been closely examined for over a decade, and future work could revolve around the specific areas of these guidelines. Research could also examine the difference between these decades and how children’s advertising has changed over time. STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 22 Future research should also include a cross-cultural analysis of children’s magazines to determine if these findings are generalizable to other cultures. Although this content analysis examined the advertisements in popular U.S. magazines, it would be interesting to see how ads in cultures that are more or less media centered would be. It would also be beneficial to examine this longitudinally as well as in other media. For example, researchers could examine how advertisements in magazines prior to 1974, when the CARU was first established (The Children's Advertising Review Unit, 2003), differ from the today. It would also be beneficial to determine whether trends in advertising to children have occurred and whether marketers are becoming more or less compliant towards the CARU guidelines. As other researchers have suggested, one area of research to examine is how children interact with the advertising they are exposed to and what impact they have on children (Krugman & Whitehill King, 2000; Moore, 2004). Another area of research may be to examine the impact that advertisements have on children in relation to their personalities. For example, a young person who is impulsive may be at greater risk to deceptive messages (Pechmann et al., 2005). Future research could attempt to explore the relationship between personality and susceptibility to the advertising message. Finally, an additional area of research to consider would be to examine which type of appeals that children and teens are particularly receptive and susceptible to, and what features in the advertisement leads to greater retention and top of mind awareness of the product. This could help define areas of problematic advertising, and possibly establish stronger guidelines and restrictions when targeting vulnerable children and adolescents (Pechmann et al., 2005), as well as help establish media literacy campaigns. STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 23 References Avery, R. K. (1979). Adolescents' use of the mass media. The American Behavioral Scientist, 23(1), 53-70. Bahn, K. D. (1986). How and when do brand perceptions and preferences first form? A cognitive developmental investigation. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(3), 382-393. Bailey, A. A. (2007). Public information and consumer skepticism effects on celebrity endorsements: Studies among young consumers. Journal of Marketing Communications, 13(2), 85-107. Bartholomew, A., & O'Donahoe, S. (2003). Everything under control: A child's eye view of advertising. Journal of Marketing Management, 19, 433-457. Basil, M. D. (1996). Identification as a mediator of celebrity effects. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 40(4), 478-495. Boush, D. M., Friestad, M., & Rose, G. M. (1994). Adolescent skepticism toward TV advertising and knowledge of advertiser tactics. Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 165-175. Brooker, G. (1981). A comparison of the persuasive effects of mild humor and mild fear appeals. Journal of Advertising, 10(4), 29-40. Campbell, M. C., & Keller, K. L. (2003). Brand familiarity and advertising repetition effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 30, 292-304. Center for Science in the Public Interest. (2003). Pestering Parents: How Food Companies Market Obesity to Children. Washington, DC. STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 24 Chan, K., & McNeal, J. U. (2006). Chinese children's understanding of commercial communications: A comparison of cognitive development and social learning models. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27, 36-56. Eagle, L. (2007). Commercial media literacy. Journal of Advertising, 36(2), 101-110. Ford, J. B., Kramer Voli, P., Jr., E. D. H., & Casey, S. L. (1998). Gender role portrayals in Japanese advertising: A magazine content analysis. Journal of Advertising, 27(1), 113-124. Friestad, M., & Wright, P. (2005). The next generation: Research for twenty-first century public policy on children and advertising. American Marketing Association, 24(2), 183-185. Geraci, J. C. (2004). What do youth marketers think about selling to kids? Advertising and Marketing to Children, 5(3), 11-17. Heinzerling, B. (1992). A review of advertisements in children's magazines. Journal of Consumer Education, 10, 32-37. Henke, L. L. (1995). Young children's perceptions of cigarette brand advertising symbols: Awareness, affect, and target market identification. Journal of Advertising, 24(4), 13-28. Holsti, O. (1969). Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Huhmann, B. A., & Brotherton, T. P. (1997). A content analysis of guilt appeals in popular magazine advertisements. Journal of Advertising, 26(2), 35-45. Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1964). The Early Growth of Logic in the Child: Classification and Seriation. . London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 25 Jennings, N. A., & Wartella, E. A. (2007). Advertising and Consumer Development. In N. Pecora, J. P. Murray & E. A. Wartella (Eds.), Children and television: Fifty years of research (pp. 149-182). Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum. Jeon, W., Franke, G. R., Huhmann, B. A., & Phelps, J. (1999). Appeals in Korean magazine advertising: A content analysis and cross-cultural comparison. Asia Pacific of Management, 16, 249-258. John, D. R., & Sujan, M. (1990). Age differences in product categorization. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(March), 452-460. Kassarjian, H. H. (1977). Content analysis in consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 4(June), 8-18. Kelly, B., & Chapman, K. (2007). Food references and marketing to children in Australian magazines: A content analysis. Health Promotion International, 22(4), 284-290. Kelly, J. P. (1974). The effects of cognitive development of children's responses to television advertising. Journal of Business Research, 2(4), 409-419. Kennedy, P. F. (1995). A preliminary analysis of children's value systems as an underlying dimension of their preference for advertisements: A cognitive development approach. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, Winter 1995, 47-56. Krugman, D. M., & Whitehill King, K. (2000). Teenage exposure to cigarette advertising in popular consumer magazines. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 19(2), 183-188. STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 26 Krugman, H. E. (2000). Memory without recall, exposure without perception. Journal of Advertising Research, 40(6), 49-54. Kunkel, D. (2005). Predicting a renaissance for children and advertising research. International Journal of Advertising, 24(3), 401-405. Linn, S. (2004). Consuming kids: Protecting our children from the onslaught of marketing & advertising. New York: Anchor Books. Macklin, M. C. (1987). Preschoolers' understanding of the informational function of television advertising. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(September), 229-239. Mangleburg, T. F., & Bristol, T. (1998). Socialization and adolescents' skepticism toward advertising. Journal of Advertising, 27(3), 11-21. Maynard, M. L., & Taylor, C. R. (1999). Girlish images across cultures: Analyzing Japanese versus U.S. Seventeen magazine ads. Journal of Advertising, 28(1), 3948. McNeal, J. U. (1991). Planning priorities for marketing to children. Journal of Business Strategy, 12(3), 12-15. McNeal, J. U. (1998). Tapping the three kids' markets. American Demographics, 20(April), 37-41. Mediamark Research, I. (2000). MRI Teen Mark 2000. New York: Mediamark Research Inc. Mehler, J., & Bever, T. G. (1967). Cognitive capacity of very young children. Science, 158, 141-142. Moore, E. S. (2004). Children and the changing world of advertising. Journal of Business Ethics, 52, 161-167. STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 27 Moore, E. S., & Lutz, R. J. (2000). Children, advertising, and product experiences: A multimethod inquiry. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(1), 31-48. Moore, R. L., & Moschis, G. P. (1978). Teenagers reactions to advertising. Journal of Advertising, 7(Fall), 24-30. Moses, L. J., & Baldwin, D. A. (2005). What can the study of cognitive development reveal about children's ability to appreciate and cope with advertising? American Marketing Association, 24(2), 186-201. Mueller, B. (1987). Reflections of culture: An analysis of Japanese and American advertising appeals. Journal of Advertising Research, 27, 51-59. O'Donahoe, S., & Tynan, C. (1998). Beyond sophistication: Dimensions of advertising literacy. International Journal of Advertising, 17(4), 32-38. Pechmann, C., Levine, L., Loughlin, S., & Leslie, F. (2005). Impulsive and selfconscious: Adolescents' vulnerability to advertising and promotion. American Marketing Association, 24(2), 202-221. Perry, D. K. (2002). Theory and research in mass communication: Contexts and consequences (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Peterson, R. T. (1994). Depiction of idealized youth lifestyles in magazine advertisements: A content analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(4), 259-269. Peterson, R. T. (2005). Employment of ecology themes in magazine advertisements directed to children: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Promotion Management, 11(2/3), 195-215. Piaget, J. (1926). The language and thought of the child. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 28 Piaget, J. (1929). The child's conception of the world. London: Routledge and Paul Kegan. Piaget, J. (1953). The origins of intelligence in children. New York: International Universities Press. Piaget, J. (1955). The Child's Construction of Reality. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Piaget, J. (1970). The stages of the intellectual development of the child. In P. Mussen, J. Conger & J. Kagan (Eds.), Readings in Child Development and Personality (pp. 291-302). New York: Harper and Row. Piaget, J. (1972). The psychology of the child. New York: Basic Books. Preston, E., & White, C. L. (2004). Commodifying kids: Branded identities and the selling of adspace on kids' networks. Communication Quarterly, 52(2), 115-128. Ritson, M., & Elliott, R. (1999). The social uses of advertising: An ethnographic study of adolescent advertising audiences. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(4), 260-277. Roedder, D. L., Sternthal, B., & Calder, B. J. (1983). Attitude-behavior consistency in children's responses to television advertising. Journal of Marketing Research, 20(Nov), 337-349. Shiv, B., Edell, J. A., & Payne, J. W. (1997). Factors affecting the impact of negatively and positively framed ad messages. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(December), 285-294. Simmons Market Research Bureau, I. (2002). Simmons 2002 Teen-Adult Combined Study. New York: Simmons Market Research Bureau. STUDENT PAPER Children’s Advertising Appeals 29 Simmons Market Research Bureau, I. (2005). Simmons Kids Study. New York: Simmons Market Research Bureau, Inc. Smith, L. J. (1995). An evaluation of children's advertisements based on children's cognitive abilities. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, Winter 1995, 2330. The Children's Advertising Review Unit. (2003). Self-regulatory program for children's advertising: The children's advertising review unit guidelines. New York: Council of Better Business Bureaus, Inc. Wackman, D. B., & Wartella, E. (1977). A review of cognitive development theory and research and the implications for research on children's responses to television. Communication Research, 4, 203-224. Ward, S., Wackman, D. B., & Wartella, E. (1977). How children learn to buy. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Weisskoff, R. (1982). Current trends in children's advertising: Children's Advertising Review Unit, Council of Better Business Bureaus, Inc.o. Document Number) Wilcox, B. L., Kunkel, D., Cantor, J., Dowrick, P., Linn, S., & Palmer, E. (2004). Report of the APA task force on advertising and children (pp. 2-64): American Psychological Association. STUDENT PAPER Table 1 Magazines Used in Study Title Nick Jr. Disney and me Fun to learn Highlights High Five Hot Wheels Magazine Ladybug Thomas & Friends Click Disney Princess My Little Pony Sparkle World Tinkerbell National Geographic Kids Barbie Highlights kiki Ranger Rick The Kids Zone WWE Kids dig Nick Sponge Bob Squarepants Girls’ Life Boys Life American Girl Discovery Girls Sports Illustrated Kids Baseball Magazine Astrogirl Beckett Hannah Montana Blast Presents Jonas Brothers Blast Presents Miley Bop Celebrity Spectacular Disney's High School Musical J-14 Children’s Advertising Appeals 30 Audience Age 0-11 2-6 2-6 2-6 2-6 2-6 2-6 3-7 3-7 3-7 3-7 3-7 5-11 6-12 6-12 6-12 6-12 6-12 6-12 6-14 6-14 6-14 6-15 6-18 7-12 7-12 7-12 7-17 9-15 9-15 Piagetian Level Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Preoperational Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Total Ads 14 3 7 3 6 0 4 0 6 1 5 4 4 6 0 0 2 1 8 0 18 4 19 18 0 13 15 23 13 4 9-15 9-15 9-15 9-15 Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Concrete Operational 0 0 7 4 9-15 9-15 Concrete Operational Concrete Operational 0 34 STUDENT PAPER Life Story Movie Magic Life Story of Miley M Miley Pop Star Quizfest Shout six 7/8 Spaces Presents the Jonas Brothers Teen Dream Twist Tiger Beat Quince Justine Teen Cicada Cosmo girl! Muslim Girl Seventeen Teen Vogue Vibe Vixen Teen Dream Children’s Advertising Appeals 31 9-15 9-15 9-15 9-15 9-15 9-15 9-15 9-15 Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Concrete Operational 5 7 27 5 16 24 0 14 9-15 9-15 9-15 10-17 11-17 12-19 12-19 12-20 12-20 12-20 12-20 12-20 12-20 Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Concrete Operational Formal Operational Formal Operational Formal Operational Formal Operational Formal Operational Formal Operational Formal Operational Formal Operational Formal Operational 0 21 33 20 112 12 13 2 87 5 85 101 18 Copyright of Conference Papers -- National Communication Association is the property of National Communication Association and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.