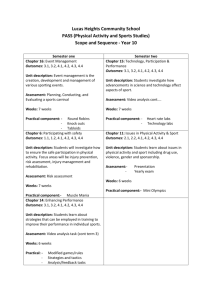

Chapter 15: Marketing of sport and leisure

advertisement