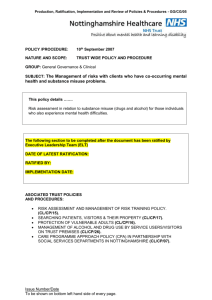

Mental Health Policy Implementation Guide

advertisement