Punctuated equilibrium and linear progression

advertisement

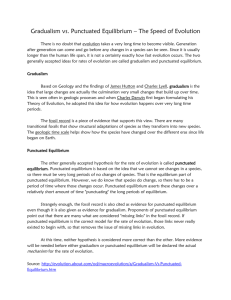

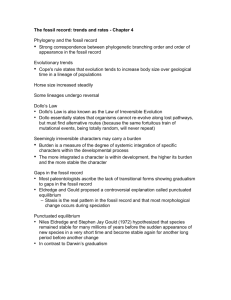

a Academy of Management Journal 2003, Vol. 46, No. 1, 106-117. PUNCTUATEDEQUILIBRIUMAND LINEARPROGRESSION: TOWARDA NEW UNDERSTANDINGOF GROUPDEVELOPMENT ARTEMIS CHANG Queensland University of Technology PRASHANT BORDIA JULIE DUCK University of Queensland This study proposes gaining a new understanding of group development by considering the integrative and the punctuated equilibrium models of group development as complementary rather than competing. We hypothesized that we would observe both punctuated equilibrium and linear progression in content-analyzed data from 25 simulated project teams, albeit on different dimensions. We predicted changes in time awareness and in task and pacing activity in line with the punctuated equilibrium model and changes in structure and process on task and socioemotional dimensions in line with the integrative model. Results partially supported predictions for both models. 1991; La Coursiere, 1980; Van de Ven, 1995; Wollin, 1999). We argue that one should not conclude that Gersick's findings discredit stage models of group development without systematically examining the relationship between the punctuated equilibrium model and linear (stage) models of group development. Only three studies (Arrow, 1997; Lim & Murnigham, 1994; Seers & Woodruff, 1997) have directly compared linear and nonsequential models of group development. However, two of the three studies appear to contain misinterpretations of some fundamental assumptions of linear group development models; both Arrow (1997) and Seers and Woodruff (1997) assumed that linear models describe a group's progression through "clearly defined" developmental stages. In fact, most linear theorists have defined developmental stages in terms of the proportion of time a group spends on issues that are characteristic of a particular stage and do not propose that clearly defined boundaries separate one developmental stage from the other (for example, Bales, 1953; Wheelan, 1994). This research note presents an empirical study designed to reconcile the punctuated equilibrium model (Gersick, 1988, 1989) and the integrative model (Wheelan, 1994) of group development. The integrative model was chosen to represent stage models because it is a recent integration of previous group development research, including Tuckman's (1965) classic model. We argue that the punctuated equilibrium model and the integrative model complement rather than contradict Group researchers were forced to reconsider their understanding of group processes when Gersick (1988, 1989, 1991) published the punctuated equilibrium model. Gersick (1988, 1989) studied eight field and eight laboratory work groups with definite deadlines, referred to as project teams, and found that instead of developing gradually over time, project teams progressed through an alternation of stasis and sudden change. Drawing on the language of biological evolution, she labeled such a course of development "punctuated equilibrium." Reviewers (e.g., Bettenhausen, 1991; Guzzo & Shea, 1992) have concluded that this new understanding of change processes challenged the traditional linear models of group development, in which (1) change was conceptualized as a gradual and incremental process, (2) it was assumed that groups progress through a logical sequence of stages over time, and (3) groups were viewed as becoming more effective over time, at least until they move into a final stage of decline and termination (Gersick, We would like to thank Andrew Wollin and Allie Perich for their help at various stages of this research. This research, conducted as part of the first author's doctoral studies at the University of Queensland, was supported by her Australian PostgraduateAward and by a Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences Early Career Research Grant to the second author. An earlier version of this research note received the 2002 Best Dissertation Award from the American Psychological Association, Division 49. 106 2003 Chang,Bordia, and Duck each other. The following discussion will clarify misunderstanding in the literature and integrate the two models to offer a comprehensive framework for understanding group development and group performance. The contribution of this study is in its attempt to clarify the literature and to convey a new understanding of group development that integrates the punctuated equilibrium model and the integrative model both theoretically and empirically. This contribution is valuable because empirical research comparing different theories of group development is largely lacking, given the extensive time and resources required to test just one group development model empirically (Weingart, 1997). THEORETICAL BACKGROUND The Punctuated Equilibrium Model Presenting her punctuated equilibrium model, Gersick (1988, 1989) argued that, instead of developing gradually over time, work groups experience long periods of inertia that are punctuated by concentrated revolutionary periods of quantum change. According to the punctuated equilibrium model, groups undergo a two-phase (rather than a two-stage) developmental pattern. Phase 1 is the first period of inertia, the direction of which is set by the end of a group's first meeting. Phase 1 lasts for half of the group's allotted time. At the midpoint of the allotted time, the group undergoes a transition that sets a revised direction for phase 2, a second period of inertia. In addition, Gersick (1989) noted that a group's progress is triggered more by members' awareness of time and deadlines than by completion of an absolute amount of work in a specific developmental stage. Moreover, "halfway" emerges as the most likely moment at which groups will call attention to time or pacing. The midpoint acts as a reminder of the approaching deadline that interrupts the group's basic phase 1 strategies and facilitates the midpoint transition and thus the onset of phase 2. The Integrative Model In the integrative model, which is based on an integration of group development research over the last four decades (e.g., Bales, 1953; Bion, 1961; Tuckman, 1965), groups are viewed as progressing through five developmental stages, each described by a unique pattern of behaviors. Stage 1 is "dependency and inclusion." According to the model, members often feel anxious and uncertain when first entering a group, because the 107 situation is new and not clearly defined. Thus, they are polite and tentative, leader-focused, and sometimes defensive. Stage 2 is "counterdependency and fight." As the group develops, members start to find the leaderfocused stage frustrating and confining. Individual members seek to clarify their roles, and the group seeks to assert independence from the leader (counterdependency). Coalitions start to form among members with similar ideas and values. Fights and conflicts between coalitions and members with different values start to emerge. Stage 3 is "trust and structure." Resolutions of the conflicts of stage 2 clarify goals, increase cohesion and member satisfaction, and reduce individual fears of rejection; thus, trust among members increases. At stage 3, communication becomes more open and task-oriented, and more mature negotiations about goals, roles, organization and procedures start to take place. Members who have accepted a role at stage 1 out of misunderstanding the group's goal or mere fear of rejection can now renegotiate their roles with the group. Stage 4 is "work." Work commences immediately after group formation but reaches an optimal state at this stage. Once goals, structures, and norms are established, a group can work more effectively. Members share the group goals and conform to the group norm of high productivity. Furthermore, as Wheelan (1994) argued, people usually have some awareness of time when they work. Groups that are always working are probably not working effectively, and those that start late are definitely not working effectively. Stage 5 is "termination." Most work groups have an ending point; even continuous groups have temporary endings such as completion of an assigned project. At each ending point, the members of a functional group tend to evaluate their work together, give feedback, and express feelings about each other and the group. Similarities and Differences between the Two Models The two models have the following similarities. First, in the integrative model, stage 1 groups are characterized by leader dependency and concerns about safety and inclusion and, thus, a group's members tend to follow the dominant mood of the group at this stage. Consequently, internal and external pressures to perform usually force groups to focus on work very early in their development, despite their unreadiness to do so. Thus, a group's members tend to embrace whatever work processes are proposed at this 108 Academy of ManagementJournal early stage. Furthermore, these work processes tend to remain with the group until members are ready to question or challenge prevailing views within the group. This argument accords with Gersick's (1988) assertion that the approach a group undertakes at its first meeting will carry through the first half of its life span, which is phase 1 in the punctuated equilibrium model. Second, it is possible that the integrative model describes changes at a more micro level within each phase of inertia described by Gersick. In the integrative model, there is only a loose boundary between stages 1 and 2 and stages 3 and 4. Stages 1 and 2 tend to co-occur to form a premature phase (phase 1 of the punctuated equilibrium model) in which group members struggle with issues such as power, structure, and intimacy; and stages 3 and 4 tend to co-occur to form a mature phase (phase 2 of the punctuated equilibrium model) in which issues such as power, structure, and intimacy are mostly resolved, and work is the main focus of a group. Thus, it is possible that a transition marks the shift of a group's behavioral pattern from a phase in which stage 1 and 2 behaviors dominate to a phase in which stage 3 and 4 behaviors dominate. This conceptualization of multilevel change patterns is similar to Wollin's (1999) recent approach to and incremental understanding revolutionary changes in social science. Wollin argued that systems have multilevel deep structures and that it is at the level of deep structure that changes determine the observed incremental or revolutionary pattern. In other words, changes at more surface levels tend to be incremental; revolutionary changes occur at a more fundamental level (Wollin, 1999). Besides the similarities, there are also some differences between the punctuated equilibrium model and the integrative model. First, in terms of specificity, the punctuated equilibrium model describes changes in the way a group works on its tasks over time, whereas the integrative model describes the overall developmental pattern of a group over time. This difference in specificity is reflected in the difference in the two coding systems. Gersick's observational system focused on "ideas and decisions that gave the product its basic shape or that would be the fundamental choices in a decision tree if the finished product were to be diagrammed... and points where milestone ideas were first proposed, whether or not they were accepted at that time" (1988: 14). The integrative model, on the other hand, was developed through use of the Group Development Observation System (GDOS; Wheelan, Verdi, & McKeage, 1993), which captures temporal changes in groups' structures February and processes along both socioemotional and taskrelated dimensions. For example, the coded transcript on the right in Table 1 demonstrates the integrative model's focus on group processes such as work (coded with "W"), flight ("FL"; avoidance of intimacy or work), and pairing ("P"), which refers to relationship building. In contrast, the left side of Table 1 demonstrates how the same group interaction would be coded under the punctuated equilibrium model. Applying the latter, we abstracted themes from the group's discussion, coding the same group interaction as the group examining its resources. Because the punctuated equilibrium model focuses a group's approach to its work, statements that represent relationship maintenance or avoidance of intimacy are less relevant. Second, in terms of generalizability, the punctuated equilibrium model describes developmental patterns that apply only to "groups that have some leeway to modify their work processes and must orient themselves to a time limit" (Gersick, 1988: 36). The integrative model was designed to describe the developmental patterns of all types of groups-for example, ICU nurse teams (Wheelan & Burchill, 1999), executive teams (Buzaglo & Wheelan, 1999), faculty member groups (Wheelan & Tilin, 1999), and financial services and hotel industry teams (Wheelan, Murphy, Tsumura, & Kyliene, 1998). HYPOTHESES Comparison of the two models described in the preceding section led to our first hypothesis: Hypothesis 1. Simulated project teams undergo both punctuated equilibrium and linear progressive developmental patterns, albeit on different dimensions. Over time, changes in a group's time awareness, pacing activities, and task activities will occur, consistent with the punctuated equilibrium model, and changes in task and socioemotional activities will occur, consistent with the integrative model. Furthermore, we argue that the presence of punctuated equilibrium does not preclude the presence of linear progression (Wollin, 1999). Hypothesis 2. The integrative model describes changes at a more micro level within each phase of inertia described by Gersick, with the midpoint transition marking a group's moving into the more productive developmental stages. 2003 Chang,Bordia, and Duck 109 TABLE 1 Meeting Transcript Sample Coded by Two Methods Gersick-Style Meeting Mapa Group Development Observational System Codingb 0:00-3:00: examined resources, looking at the tapes available. B These are all the music tapes (W) A tapes (W) C I wonder what the music is? (W) B while you are sleeping (W), silk road of theme (W), pearl shells (W), which I never hear of (FL),while you are sleeping (W), is that the movie? (FL) A hm (FL) C yes (W) B we should use that one (W) 0:30-1:30: proposed content. One person talked about the movie "CrazyPeople." Wanted to use the idea shown in the movie: "Millions of people get killed every year but we have the fewest number."The group then evaluated the proposed content-"not original." 1:30-4:20: listened to all the music tapes, commented on the music, and proposed ideas that go with the music. "This is captain someone," "This is like an Asian music," "Butthat doesn't make Asian sound exciting, it just makes it sound relaxing.""We'vealso got to mention the country I guess." D ... (U) A I am not going to play it (W), I am just going to... (W) D ok (W) E has any one seen crazy people (FL) D pardon (U) E crazy people (FL),the movie (FL) B no (answeringB) (FL),that's good (referringto the tape recorder)(W), C ok so (W), so we got to basically advertise (W) E they did this thing on the movie (W) where there like was this advertising guy (W), and you know like how they usually say those safety stuff (W) 1:00 E and he goes millions people got killed every year but we have the fewest number (W), like people get killed (W) D oh, really (P) E they just do all this crazy thing (FL)and people really like it (FL)cause he just like do all these crazy commercials (W) B that's good though (W) E but all these crazy people helps him to make up these ideas (FL),but it's not original (W), but its creative (W) C but they wouldn't know whether it's not original (W) unless they have seen it (W) D yeah (W), but they have the tape (W) Ebut.. .(U) oh yeah (W) E elevating music (playing music tape 1) (W) B it's like airplane music when you land (W) A oh. Yeah (W) D or when you are taking off (W) A yeah (P), it's true (W) E what's that (the music) (W) 2:00 B so we would have to like do the other ones... a The left-hand column is a five minute-sample segment of the meeting map describing changes in the central theme of a group's discussion over time. This map was constructed following guidelines provided by Gersick(1989). The coding of the segments is in bold type. The numbers in the left column represent minutes elapsed since project inception. b The right-handcolumn shows a GDOStranscriptfor only two minutes of the group's interaction. The letters at the start of each line identify group members.The coding of each statement is in parentheses, in bold type. The coding reflects the purpose of the communications and the nonverbalbehaviors accompanying them. In this study, we aimed to test the hypotheses by replicating Gersick's (1989) laboratory study on simulated work groups. Laboratory groups were studied because their development could be observed from project inception to termination. More importantly, a laboratory study offered a controlled environment in which similarities and differences between the two models could be the most effectively investigated. Furthermore, Gersick demonstrated that laboratory groups display developmental patterns that are similar to those of field groups and thus that data derived from laboratory groups have external validity. The integrative model (Wheelan, 1994), in contrast to the punctuated equilibrium model, was developed in the field and has not been tested in a laboratory setting. However, given that the model is generalizable to a wide range of groups, we expected laboratory groups to display similar developmental patterns, with the exception that the laboratory setting might lead to less socioemotional interaction and/or conflict as participants would 110 Academy of ManagementJournal have limited vested interest in the task and would only be interacting for 40 minutes. METHODS Participants and Procedures Twenty-five groups of first-year university psychology students (8 groups of five and 17 groups of four) participated in the experiment for partial fulfillment of psychology course requirements. The sample consisted of 69 female and 38 male students that formed 2 all-male, 7 all-female, and 16 mixed groups. Groups' gender composition was not controlled in this experiment because previous research (Verdi & Wheelan, 1992) has suggested that it has no influence on patterns of group development. However, observation of the groups' interaction showed that the all-male groups were less committed to the task than were the other groups. The task in our study was modeled closely on that in Gersick's (1989) laboratory study. Participants were told to assume the role of professional advertising writers at a major urban radio station who were to design a pilot commercial for a wellknown airline. Each team received a folder that informed them about the client's special request and the costs of producing an advertisement. Each group also received an audio tape player, a tape recorder, and three different music tapes. The budget allowed each group to use only one of the music tapes. Participants were asked to note the time their group began on their watches and to have the radio commercial ready for collection when the experimenter (one of the authors) returned in exactly 40 minutes. Participants were told that several other advertising agencies were interested in this project as well and that if their team did not produce a pilot commercial that satisfied the client, their agency would lose this contract. The competition was intended to motivate the students to finish on time and to attend to the requirements and evaluation criteria. At the end of the 40 minutes working time or upon completion of a group's first presentable product (whichever occurred first), the experimenter returned to the room and debriefed the participants. Meetings were videotaped for further analysis. Each group's interaction was transcribed word-for-word into a written script for coding and analysis; the average script contained 26.8 (s.d. = 5.48) pages of double-spaced, 12-point type and 1,113 (s.d. = 269.32) complete sentences. The Coding Systems Coding for the punctuated equilibrium model. Responses were coded as far as possible according February to the coding scheme described by Gersick (1989), although she did not fully describe a unit of analysis for testing the punctuated equilibrium model. Her coding system contained two broad classes. The first categorized the actions group members took to manage a work process. There were three types of action statements: Process statements ("P") were members' suggestions about how their group should proceed with the work (for instance, "Why don't we just toss out some ideas that we could get into the commercial?"). Time-pacing statements ("T") were group members' direct references to time-noting what time it was or how much time had elapsed or was left-and members' attempts to pace their group by saying when, in terms of the allotted time, something should be done (for example, "toward the end" and "before too long") or by mentioning how long an action would take, or finishing on time (for instance, "We have got 20 min- utes left!"). Resources-requirements ("R") statements were members' references to their group's resources, requirements, or criteria for the task and explicit attempts to shape the product in accordance with the group's resources or requirements (for instance, "That's $200 per thing, so we basically have the choice of one."). The second class of categories included statements about the product: Content statements ("#c") were group members' mentions of selling points to be pushed in the ad, ideas for content themes or story lines, the content of dialogue, or information to be presented. Detail statements ("#d") were ideas about small modifications or fine points of ad content (for instance, "Should the brakes slam or not?"). Format statements ("#f") were ideas for the basic format of the ad, the vehicle through which the information would be conveyed (for instance, "What if we had a conversation between two people?"). Procedure statements ("#p") were ideas about the process of acting out the ad and about who would do what for the recording session (such as "I'll do the second person."). Following procedures similar to those reported by Gersick (1989), we constructed a qualitative map for each group (see Table 1). The map described changes in the central theme of a group's discussion over time. Observation System Group Development (GDOS) coding for the integrative model. Work statements ("W") were those that represented purposeful, goal-directed activity and task-oriented efforts (for example, "Why don't we start writing this down?"). All categories described by the punctuated equilibrium model were coded as work statements in the GDOS coding. Fight statements ("FI") were those that implied argumentativeness, criticism, or aggression (such as "That is a stupid 2003 Chang,Bordia, and Duck idea."). Flight statements ("FL") were those that indicated avoidance of the task and confrontation (such as "Did anyone watch the movie on SBS last night?"). Pairing statements ("P") were those that included expressions of warmth, friendship, support, or intimacy with others (for example, "Good work, John!"). Counterpairing statements ("CP") indicated avoidance of intimacy and connection and a desire to keep the discussion distant and intellectual (for example, "Can we talk about the commercial instead?"). Dependency statements ("D") showed an inclination to conform with the dominant mood of the group or to follow suggestions made by the leader and, generally, demonstrated a desire for direction from others (for example, "What do you think we should do?"). Counterdependency statements ("CD") asserted independence from and rejection of leadership, authority, or other members' attempts to lead (such as "Why don't we try my idea first?"). It should be noted that all statements needed to be coded on the basis of their purpose, the group's history, the nonverbal cues given by the speaker, and the reaction of the recipient. For example, "Can we talk about the commercial instead?" was coded as a counterpairing statement when it was a reaction to a group's conversation. In contrast, relationship-building "Did any one watch the movie on SBS last night?" was coded as flight when it was stated to avoid working on the commercial, when the group found the task too difficult to proceed with. The first author coded all the transcripts twice, once with Gersick's coding system, and once with the GDOS. A research assistant coded a randomly selected 10 percent of the scripts. Coefficients for interrater reliability between the first author and the research assistant were calculated both for unitizing and for coding. For all of the integrative model codings and for the pacing and time awareness statements of the punctuated equilibrium model, a unit was defined as a simple sentence that presents a complete thought to another person or persons. A unit did not have to be a grammatical sentence as long as a communication provided enough information that it could be interpreted by others and could stimulate a reaction in them. Thus, "I agree" is a unit, and "Absolutely" is a unit if said in response to another statement (Wheelan et al., 1993: 44). Unitizing reliability was assessed using Guetzkow's U, and the global and categoryby-category reliability measures of the GDOS were calculated using Cohen's kappa (Folger, Hewes, & Poole, 1984). The unitizing reliability was calculated to be 0.99 for the integrative model. The global level of interrater reliability was 0.74 for the integrative model, and the category-by-category 111 reliability coefficients for work, flight, pairing, counterpairing, dependency, counterdependency, uncodable, and pacing and time statements were 0.99, 1.00, 0.94, 0.97, 0.81, 0.75, 1.00, and 1.00 respectively. Cohen's kappa was not calculated for the fight category because no fight statements were observed in this study (see below). For the punctuated equilibrium model, interrater reliability was only calculated on the percentage of agreement on the linear or nonsequential pattern of development and for the time and pacing statements (as described above). We relied on these two measures because of the lack of detail in Gersick's (1989) paper on how to analyze the data from other coding categories. Another research assistant who had not been involved in the initial coding of the transcripts used GDOS to code 25 percent of the transcripts; the percentage of agreement between this research assistant and the first author on the linear/ nonsequential pattern of development was 100 percent. For all observed transitions, the two raters also agreed on the timing of the transitions and the events that constituted them. RESULTS The Punctuated Equilibrium Model Support for the punctuated equilibrium model was assessed in two ways: First, via examination of the overall pattern of attention to time and pacing throughout a group's allotted time and second, through examination of qualitative shifts in the way the group performed its task. Figure 1 demonstrates the distribution of pacing and time statements across all 25 groups. The groups showed more awareness of pacing as time progressed. To examine whether this pattern of increase in time awareness might be interpreted as both linear and nonsequential, we performed two separate Friedman's chi-square analyses (Howell, 1990). In the first analysis, we compared time awareness in the two phases (20 minutes each) to replicate Gersick's finding. In the second, we examined time awareness across the four 10-minute time intervals to determine if there was evidence of a gradual increase in time awareness over timethat is, a linear trend. A Bonferroniadjustmentwas made so that alpha was set to .025 for the two "main effect" analyses and to .004 for the four "pairwise" comparisons. Results of the two chi-square tests supported both a nonsequential and a linear increase in time awareness. Time awareness significantly increased between the phases: phase 2 contained 65 time references, as compared to 34 in phase 1 (X21 = 112 Academy of ManagementJournal February FIGURE 1 Patterns of Time Statements Collapsed across the 15 Groupsa # # #f # ## ---5 # ## # #### ## ## # #### # ### ### # # ### ####### ######## ################ # #########I####################### ----10 ---- 15----20----25----30----35----40 Time a Each "#" represents the time statements of a different group. 9.71, p < .01). The four-stage chi-square test showed a significant difference in groups' time awareness over the four 10-minute intervals; there were 14, 20, 26 and 39 time references over these periods (X23 = 13.85, p < .01). Furthermore, pairwise comparisons of the time awareness statements across the four 10-minute intervals showed that the only significant difference in time awareness was = 11.79, p < .001; between intervals 1 and 4 (X21 X21 = 1.06, 0.78, and 2.60 for the comparisons between intervals 1 and 2, 2 and 3, and 3 and 4, respectively). Thus, both linear and nonsequential changes of time awareness were observed in this study. To understand if the published data from Gersick's (1989) study could also be interpreted as supportive of both linear and nonsequential patterns, we reanalyzed those data and found a similar pattern. When the group's allotted 60 minutes was divided into four 15-minute intervals, a significant difference in time awareness was found (X23= 9.57, p < .0025; 7, 12, 14, and 23 time references), and none of the pairwise comparisons were significant except for the comparison between intervals 1 and 4 (X21 = 8.53, p < .001; X21 = 1.32, 0.15, and 2.19 for the comparisons between intervals 1 and 2, 2 and 3, and 3 and 4, respectively). Thus, reanalysis of Gersick's data also indicated that the results could be interpreted as both linear and nonsequential, depending on the unit of analysis that is used (see Wollin, 1999). Midpoint Transition Using Gersick's coding system as a guideline, we constructed a time map describing the changes in the central theme of discussion over time for each group; Table 1 presents an example of a map. Nine of the 25 groups studied here showed some form of transition around the midpoint of their allotted time. A transition point was defined by Gersick as "the moment when group members made fundamental changes in their conceptualization of their own work" (1989: 277). Gersick argued that this shift could occur in two ways: "One way consisted of summarizing previous work, declaring it complete, and picking up a next subtask. A second way was observed in groups whose phase 1 agendas appeared to be floundering. These groups just dropped stalled phase 1 approaches and reached out for a fresh source of inspiration, something around which to crystallize further efforts" (1989: 303). Like Gersick, we observed that transitions that occurred around the midpoint were most likely to focus on new content or a new format that would help a group to integrate the materials generated up to that point to create the basic structure of the commercial. For example, one group spent the first half of its time talking about possible content ideas for the commercial. After 19 minutes of discussion, one member said, "All I can think of is 'I Like Aeroplane Jelly'" (a reference to a jingle in an existing TV ad). Another group member responded, "We can change the words of 'I Like Aeroplane Jelly' to 'I Love Air Australia."' This suggestion was not immediately taken up by the group, but 2 minutes later the group used this idea and started making up words for this song, which became a major part of the commercial. Gersick (1989) studied 8 groups in the field and 8 groups in the laboratory. In both cases, she found midpoint transitions in most groups. She concluded that the midpoint is the most likely, but not the only, transition point in project teams. However, in our study, with a larger sample of 25 groups, we found that only 9 groups underwent midpoint transitions. The other 16 groups fitted the description of linear progression more closely than that of a progression marked by a midpoint transition. Small and incremental changes occurred throughout these groups' life spans, without clear, 2003 Chang,Bordia, and Duck sudden changes in direction. Nevertheless, of the 16 groups that did not display midpoint transitions, 12 did undergo some transitions, most of which occurred within the first 10 minutes of their life spans. The presence of both linear progressive and patterns illustrated punctuated developmental that groups can follow various developmental equilibrium, linear propatterns-punctuated gression, or a combination. This finding is not surprising, given that, even with a sample size of 8 groups, Gersick observed two ways of making the midpoint transition. More importantly, the first way of making a transition she observed (summarizing previous work, declaring it complete, and picking up a next subtask) describes elements of linear progression as well as elements of nonsequential transition. Variations in the "sizes" of transitions and the number of transitional points resulted in our observation of multiple developmental patterns. The results of this study accorded with those of Lim and Murnighan (1994), who found that changes in negotiation activities over time could be interpreted as forming either a nonsequential pattern in which a transition point occurred immediately before a deadline, or as forming a linear pattern in which gradual and incremental changes occurred throughout a group's life span. Lim and Murnighan suggested that their study did not necessarily discredit the punctuated equilibrium model; rather, they saw it as demonstrating that if a group does display nonsequential developmental patterns, the nature of the task has a dramatic impact on when in the group's life span a transition will take place. The fact that most of the groups in the present study did show some form of transition during their life spans supported the validity of the punctuated equilibrium model but, like Lim and Murnighan (1994), we found that transitions do not always occur at the midpoint. The Integrative Model To examine group developmental patterns from the perspective of the integrative model, we divided the groups' 40 minutes of allotted time into four 10-minute intervals. For each interval, the proportion of time allocated to each category was calculated by dividing the number of statements made in that particular category by the total number of statements made. Figures 2a-2e illustrate the developmental patterns of the groups over time. Visual inspections of the data were conducted as a starting point to the interpretation of the results. 113 Inferences based on the visual inspections are crucial to this study; given the low statistical power of the study, we did not expect many of the statistical tests to be significant. The figure does not contain counterpairing and fight graphs. With only one group yielding only two counterpairing statements, these were very rare, possibly because group members' personal involvement in the task was low. The standard deviations for all five categories were large, although this was more a result of the groups' displaying different baselines (for example, some groups spent 40 percent of their time on flight and others spent less than 10 percent of their time on flight) than a consequence of their displaying different developmental patterns. We inferred general developmental trends from the data aggregated for the 25 groups. Friedman's rank tests were performed on this aggregated data for each category as a means to determine if there was any significant difference in the amount of time allocated to the particular category over the four time intervals. No statistical adjustment was made because the categories are mutually exclusive. If a significant chi-square was obtained for the particular category, we conducted a series of pairwise comparisons using Friedman's rank test (with an alpha set to .008, after the Bonferroni adjustment) to determine whether the changes over time were linear or nonsequential. Work. As expected, work statements dominated the groups' interactions at all times. Roughly 70 to 80 percent of the statements were work statements. Visual inspection of Figure 2a and the Friedman's rank tests support the integrative model hypothesis that attention to work will increase gradually over time. There was a significant difference in the proportion of time allocated to work statements over the four time intervals (X23 = 26.67, p < .0001). Follow-up pairwise comparisons showed that differences in the amount of work in adjacent time segments were nonsignificant, whereas comparisons between nonconsecutive time segments were = 14.44, 11.56, and 10.67, p < .001 significant = 1.5; for times 1 (X21 and 4, 2 and 4, and 1 and 3; 1.5 and 6.0, n.s., for times 1 and 2, 2 andX21 3, and 3 and 4, respectively). Flight. In contrast, flight statements only occupied 6 to 7 percent of groups' interaction time. Most flight statements were made to avoid the task rather than to avoid confrontation in the group. Visual inspection of Figure 2b supports the integrative model prediction that flight statements will increase at time 2 and then decrease over time 3 and time 4. However, the difference in flight over time was not statistically significant (x23 = 2.79, n.s.). 114 Academy of ManagementJournal February FIGURE 2 Developmental Patterns Averaged across the 15 Groupsa (2a) Work Statements 100% (2b) Flight Statements 30% 25% 80% - 20% 60% - 15% 40% 10% 5% 20% 0% 0% -5% Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 Time 4 Time 1 Time 3 Time 4 (2d) Dependency Statements (2c) Pairing Statements 30% Time 2 - 30% 25% 20% 20% 15% 10% 10% 5% 0% 0% Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 Time 4 Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 Time 4 (2e) CounterdependencyStatements 5% 4% 3% 2% 1% 0% -1% Time 1 a Time 2 Time 3 Time 4 The five graphs describe the means and standard deviations of the work, pairing, dependency, statements made over the four 10-minute intervals. Pairing. Pairing statements occupied 10-16 percent of the groups' interaction. Most pairing statements were made to show reflective listening to other group members. Visual inspection of Figure 2c and the Friedman's tests led to the conclusion that the proportion of time allocated to pairing statements gradually decreased over time. There was a significant difference in the proportion of time allocated to pairing statements over the four time intervals (X23 = 20.75, p < .0001). Pairwise comparisons showed that pairing statements stayed relatively constant from time 1 to time 3 and decreased significantly at time 4 (X,21 = 8.9, 13.5, and 8.17, p < .004 for times 3 and 4, 1 and 4, and 1 and counterdependency, and flight 3; X21 = 0.0, 1.63, and 6.0 for times 1 and 2, 2 and 3, and 2 and 4, respectively). According to the integrative model, the proportion of time allocated to pairing should increase gradually over time until groups reach the trust stage (stage 3), and then decrease slightly at the work stage (stage 4). Neither visual inspection of the graph nor the Friedman's rank tests supported this pattern of development. Instead, both suggested that pairing decreased slowly over time, especially at time 4. The lack of increase in pairing over time could be explained by the artificial group setting. Given that these simulated work groups were highly task- 2003 Chang,Bordia, and Duck oriented and that group members had no expectations of future interaction, they might not have felt the need to engage in the maintenance activities likely to occur in naturally occurring work groups. A lack of socioemotional activity is expected in laboratory groups; however, the proportion of time allocated to pairing statements (ranging from 16 to 10 percent) was much lower than that observed in other studies using similar groups (e.g., Bales, 1953). On the other hand, the decrease in pairing statements at time 4 is supportive of the model. Dependency. Dependency statements occupied only 3-5 percent of the interaction time. However, this category was expected to have low frequencies because the groups did not have designated leaders. Visual inspection of Figure 2d and the Friedman's tests support the integrative model argument that dependency will decrease gradually over time. There was a significant difference in the proportion of time allocated to dependency statements over the four time intervals (X23 = 13.85, p < .003). Pairwise comparisons showed that only the difference between time 1 and time 4 was significant at the adjusted alpha level (X2, = 9.78, p < .002; X21 = 0.18, 0, 0.65, 5.0, 3.85, n.s., for times 1 and 2, times 2 and 3, times 3 and 4, times 1 and 3, and times 2 and 4, respectively). Counterdependency. Counterdependency statements occupied only 1 percent of the groups' interaction time. This category was expected to be of very low frequency because of the groups' artificial settings and the group members' lack of vested interest in the task. Visual inspection of Figure 2e suggests that counterdependency statements were highest at time 2, and slightly lower at time 1, but much lower at time 3 and time 4, supporting the integrative model argument that counterdependency will be higher in the early stages of group development (stages 1 and 2) and lower in the later stages of group development (stage 3 and 4), with a peak occurring at the counterdependency/fight stage. However, this result needs to be interpreted with caution because, although there was a significant difference in the proportion of time allocated to counterdependency statements over the four time intervals (X23 = 9.83, p < .02), no pairwise comparisons were significant at the adjusted alpha level of .008 (X21= 2.0, 4.5, 1.8, 1.8, 1.8, and 5.4 for times 1 and 2, 2 and 3, 3 and 4, 1 and 4, 1 and 3, and 2 and 4, respectively). DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION In summary, results of this study partially support developmental trends that are in line with the integrative model. According to this model, in a group, 115 statements showing attention to work and pairing should increase over time, whereas those indicating dependency should decrease over time. Furthermore, the integrative model prediction is a peak in counterdependency, fight, and flight statements in phase 2 of a group's development and a decrease from there onward. Results of this study support the predicted pattern of change for work and dependency, but not for pairing. Visual inspections of changes in flight and counterdependency also support the predicted patterns, although corresponding statistical tests conducted at a conservative alpha level do not. Moreover, no fight or counterpairing statements were observed in the groups' interaction. On the other hand, results of this study also suggested some reservations concerning the use of the Group Development Observation System (Wheelan et al., 1993) with laboratory work groups. As expected, the ad hoc laboratory groups in this study were very task-focused, and it was difficult to study group development on the socioemotional level. Results of this study supported Hypothesis 1. Both punctuated equilibrium and linear progression were observed simultaneously in simulated project teams, with the dimension of observation and the unit of analysis accounting for the type of development that was observed. The punctuated equilibrium model describes changes in a group's time awareness and pacing activities over time as well as changes in its task activities over time. The integrative model, on the other hand, describes changes in a group's structure and process along both task and socioemotional dimensions. The different scales of changes described by the two models can be seen by comparing the coding of a sample transcript made using the GDOS with a meeting map of the same interaction constructed using Gersick's coding system (see Table 1). For example, in the first 30 seconds of the group's interaction, group members showed avoidance of the task by engaging in off-task discussion of whether the music provided by the experimenter was taken from a movie. This information would be coded by the GDOS as an indication of the group's flight away from the task. However, when one examines the central theme of the group's task-oriented discussion, this information would simply be coded as part of the group's listening to and commenting on the music tapes provided. Thus, the GDOS aids understanding of subtle changes in a group's processes and structure, whereas Gersick's coding system guides understanding of the overall changes in a group's approach to its task. The two models complement each other to provide rich information on the developmental patterns of project teams over time. Results of this study also demonstrate that 116 Academy of ManagementJournal changes in pacing and time statements can be interpreted as both linear and nonsequential, depending on the unit of analysis used. This finding highlights the significance of the unit of analysis in determining the developmental patterns that are observed in groups. The work conducted following the punctuated equilibrium model used a larger time frame (20 minutes) and demonstrated discontinuous change from phase 1 to phase 2, whereas the integrative model work used a smaller time frame (10 minutes) and demonstrated incremental changes over times 1, 2, 3, and 4. With the exceptions of the absence of an increase in pairing statements and the nonsignificance of the change in flight statements over time, the overall pattern of changes in GDOS categories closely matched the integrative model's predicted pattern, thus supporting the developmental sequence proposed in the linear model. However, post hoc pairwise comparisons for the work and pairing statements also suggested that the patterns of change could be described as an incremental step occurring between times 1 and 2 combined and times 3 and 4 combined, rather than as linear increase over times 1, 2, 3, and 4. This pattern of results suggested that the midpoint transition also marked the group's resolution of early developmental issues such as leadership and work structure and a move forward in the production of the pilot commercial. This pattern-groups' moving toward more productive developmental stages (3 and 4) after a midpoint transition-was further supported by thematic changes in the discussions: In most cases, midpoint transitions moved the groups from an earlier conversation on the content and process of the commercial to later dialogue on procedure and on details of the commercial. Furthermore, most groups displayed more effective structuring (such as forming subgroups to work on different aspects of the task) toward the ends of the their life spans. Thus, we conclude that Hypothesis 2 is also supported. The integrative model appears to describe changes at a more micro level within two phases of inertia. This finding accords with Wollin's proposition that punctuated equilibrium should be viewed as "a stepped continuum of change in an organizational system, from revolutionary discontinuous change to more incremental change, reflecting the different levels of its deep structure" (1999: 365). The results of our study clarify an apparent misunderstanding in the current group literature whereby Gersick's (1988, 1989) work is typically perceived as contradicting the linear developmental patterns proposed in traditional stage models (e.g., Bettenhausen, 1991; Guzzo & Shea, 1992). Our study demonstrates that both the integrative model February and the punctuated equilibrium model describe valid developmental patterns of project teams. Furthermore, the two models complement each other to better inform researchers and practitioners on the development of different aspects of a group's functioning. Depending on the temporal dimension they are interested in, researchers and practitioners working with organizational project teams can choose either the integrative model or the punctuated equilibrium model. For example, when planning to implement significant change in a work group, a change agent can use insights from both models to prepare the group for the upcoming change. First, the agent can work with the group on early developmental issues to facilitate trust among group members and effective work processes (using the integrative model), and can thus enhance the group's ability to cope with interruptions to work flow. Second, the change agent can then introduce small internal or external changes to interrupt the group's current state of inertia and create an environment of instability, which will in turn increase the group's propensity for larger changes (using the punctuated equilibrium model). For example, replacing a group member can facilitate the group's examination of current structure and processes and thus provide opportunities for introducing changes to one or both aspects (Arrow & McGrath, 1993). Once changes have been introduced, early developmental issues might need to be revisited (the integrative model) to facilitate effective work under the new working conditions. By integrating the two models, change agents can help groups to make tranand in a preferred sitions more successfully direction. The artificial laboratory setting and the small sample here are the study's most important limitations. It was clear from the observational data that these simulated work groups in a laboratory setting did not display the same socioemotional development that naturally occurring work groups do, so we could not test some specific predictions based on the integrative model. However, the resource intensity of group development observational re- search makes it difficult to study field groups using similar coding schemes. Thus, in the future, researchers should aim to both streamline the present coding system so it can be used for field studies and to conduct more laboratory studies in controlled environments with creative interventions that promote the socioemotional development of the simulated work groups. 2003 Chang,Bordia, and Duck REFERENCES Arrow, H. 1997. Stability, bistability, and instability in small group influence patterns. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72: 75-85. Arrow, H., & McGrath,J. E. 1993. Membership matters: How member change and continuity affects small group structure, process, and performance. Small Group Research, 24: 334-361. Bales, R. F. 1953. The equilibrium problem in small groups. In T. Parsons,R. F. Bales, &E. A. Shils (Eds.), Working papers in the theory of action: 111-161. New York:Free Press. Bettenhausen, K. L. 1991. Five years of groups research: What we have learned and what needs to be addressed. Journal of Management, 17: 345-381. Bion, W. R. 1961. Experiences in groups. New York: Basic Books. Buzaglo, G., & Wheelan, S. A. 1999. Facilitating work team effectiveness: Case studies from central America. Small Group Research: 30: 108-129. Folger, J. P., Hewes, D. E., & Poole, M. S. 1984. Coding social interaction. In B. Dervin & M. Voight (Eds.), Progress in communication sciences, vol. 4: 115161. Norwood, NJ:Ablex. Gersick, C. J. 1988. Time and transition in work teams: Toward a new model of group development. Academy of Management Journal, 31: 1-41. 117 forces: Group development or deadline pressure. Journal of Management, 23(2): 169-187. Tuckman, B. W. 1965. Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63: 384-399. Van de Ven, A. 1995. Explaining development and change in organizations.Academy of Management Review, 20: 510-540. Verdi, A. F., &Wheelan, S. A. 1992. Developmental patterns in same-sex and mixed-sex groups. Small Group Research, 23: 356-378. Wheelan, S. A. 1994. Group processes: A developmental perspective. Sydney: Allyn & Bacon. Wheelan, S. A., & Burchill, C. 1999. Take teamwork to new heights. Nursing Management, April: 28-31. Wheelan, S. A., Murphy, D., Tsumura, E., & Kline, S. F. 1998. Memberperceptions of internal group dynamics and productivity. Small Group Research, 29: 371-393. Wheelan, S. A. & Tilin, F. 1999. The relationship between faculty group development and school productivity. Small Group Research, 30:59-81. Wheelan, S., Verdi, R., & McKeage,R. 1993. The Group Development Observation System: Origins and applications. Philadelphia: PEP Press. Wollin, A. 1999. Punctuatedequilibrium:Reconcilingtheory of revolutionaryand incrementalchange. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 16: 359-367. Gersick,C. J. 1989. Markingtime: Predictabletransitions in task groups. Academy of Management Journal, 32: 274-309. Gersick, C. J. 1991. Revolutionary change theories: A multilevel exploration of the punctuated equilibrium paradigm.Academy of Management Review, 16: 10-36. Guzzo, R. A., &Shea, G. P. 1992. Groupperformanceand intergrouprelations in organizations. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.),Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed.), vol. 3: 269-313. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Howell, D. C. 1990. Statistical methods for psychology. Belmont, CA: Duxbury Press. LaCoursiere,R. B. (Ed.). 1980. The life cycle of groups: Group development stage theory. New York: Human Science Press. Lim, S. G. S., &Murnighan,J.K. 1994. Phases, deadlines, and the bargainingprocess. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 58: 153-171. Seers, A., & Woodruff, S. 1997. Temporal pacing in task Artemis Chang (a2chang@qut.edu.au)is a lecturer in the School of Management at Queensland University of Technology. She received her doctoral degree from the University of Queensland. Her research interests include group processes and performance,time, change, human resource information systems, and employee turnover in the IT industry. Prashant Bordia (Ph.D., Temple University) is a senior lecturer in the School of Psychology, University of Queensland. His research interests include group development, computer-mediated communication, and rumors in organizations. Julie Duck (Ph.D.,University of New England)is a senior lecturer in the School of Psychology at the University of Queensland. Her current research focuses on group and intergroupprocesses, especially as they apply to organisational contexts and to the impact of mass communication on perceptions, attitudes, and behavior.