Vol. 34 No. 2

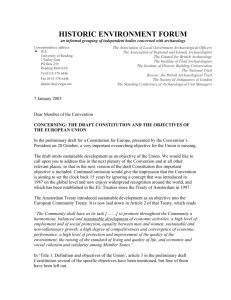

advertisement