Crusader for bees - Farm Progress Issue Search Engine

advertisement

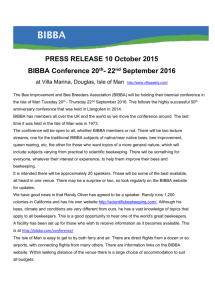

6 www.FarmProgress.com ● October 2014 The Farmer Minnesota NewsWatch Crusader for bees By LIZ MORRISON OMMERCIAL beekeeper Steve Ellis of Barrett is only half-joking when he says, “These days, I have two jobs — beekeeping and pesticide policy.” Ellis and other commercial beekeepers are sounding the alarm about the role of agricultural pesticides in declining pollinator health. “Part of my business now is education on this issue,” says Ellis, secretary of the National Honey Bee Advisory Board, which works on national pesticide issues. Honeybees — a vital part of agriculture — are failing to thrive as they once did. “We have a sick industry,” he says. Honeybee die-offs in the U.S. have risen sharply since 2006. Winter losses for the past eight years have averaged 30%, according to annual USDA surveys. Colony losses over the spring and summer — previously rare — are also up. Many beekeepers are blaming a widely used class of systemic insecticides called C Key Points ■ Higher bee mortality has numerous cause possibilities. ■ Federal funds are available to improve bee habitat. ■ Minnesota established a team to investigate bee die-offs. neonicotinoids. Farmers know these chemicals as Gaucho, Cruiser, Poncho and others. Virtually all corn seeds and most soybean seeds are coated with “neonics.” They are also used extensively on nursery plants. In 2013, Ellis and other beekeepers sued the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, asking for a moratorium on neonicotinoids until an expanded regulatory review is finished. However, this is not a farmer versus beekeeper issue, Ellis insists. “Farmers need beekeepers and beekeepers need farmers,” he says. Beekeepers are seeking a reasoned, level-headed approach that would protect against the harmful effects of pesticides and still allow their proper and judicious use. Multiple stressors At this point, the causes of higher honeybee mortality rates are still unclear, says Robert Koch, University of Minnesota Extension entomologist. Research points to a combination of factors, including diseasecarrying varroa mites, a shortage of nutritious food sources and exposure to insecticides. Neonicotinoids are extremely toxic to bees, Koch says. Research from Purdue University found that bees can be directly or indirectly exposed to these insecticides through contact with contaminated dust from treated seeds, soil or dosed plants. Like SOOTHING SMOKE: Steve Ellis prepares a smoker: one of the beekeepers’ tools for managing honeybees. Smoke calms the bees, letting the beekeepers handle them. QUEENS’ PALACE: Beekeeper James Cook holds a crate that housed queens. In the early spring, beekeepers increase their livestock numbers by dividing colonies and adding new queens. To protect pollinators, avoid ‘insurance’ pesticide applications U SE insecticides only when they are really needed. That’s the single most important thing farmers can do to protect honeybees and other pollinators, says Robert Koch, a University of Minnesota Extension entomologist. Growers should scout regularly, identify pests and treat with foliar insecticides only if insect numbers reach economic thresholds. “If you treat at lower levels, you are unnecessarily exposing pollinators to insecticides, not to mention spending money for no yield benefit,” he says. Beekeepers are convinced that overuse of pesticides is contributing to declines in honeybee health, says commercial beekeeper Steve Ellis, Barrett. As livestock farmers themselves, beekeepers understand that there are pests and bad bugs to manage. However, all farmers have to be more discriminating in how they manage them. Ellis says it would be helpful if farmers restricted the use of insecticide seed treatments to high-risk areas, an approach that’s being taken in Ontario, Canada. Insecticidal seed treatments can provide effective protection from seed- and seedling-feeding pests and are an important tool in fields with high risk for such pests, Koch says. However, widespread prophylactic use of systemic insecticidal treatments across many acres, regardless of pest risk, is counter to the philosophy of integrated pest management, he says. Many times, growers may not get a benefit from insecticide seed treatments. Unfortunately, Koch adds, some growers complain that they can’t get untreated seeds. In addition to avoiding preventive or “insurance” insecticide use, Koch says, farmers can protect pollinators by: ■ handling treated seed carefully to avoid spreading toxic dust over the landscape ■ spraying in the evening, when bees are not foraging ■ choosing pesticides that are less toxic to bees or have shorter residual activity ■ minimizing drift In general, Ellis finds that most farmers he speaks with are sympathetic to the plight of bees. “The farm community wants to know, what’s the deal with bees and what can we do to help?” he says.