Shared Symbols and Cultural Identity The Goddess Tyche on Coins

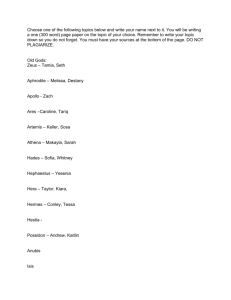

advertisement